Big Wall Bivouacs and "camping" part1

Tools for the Wild Vertical by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

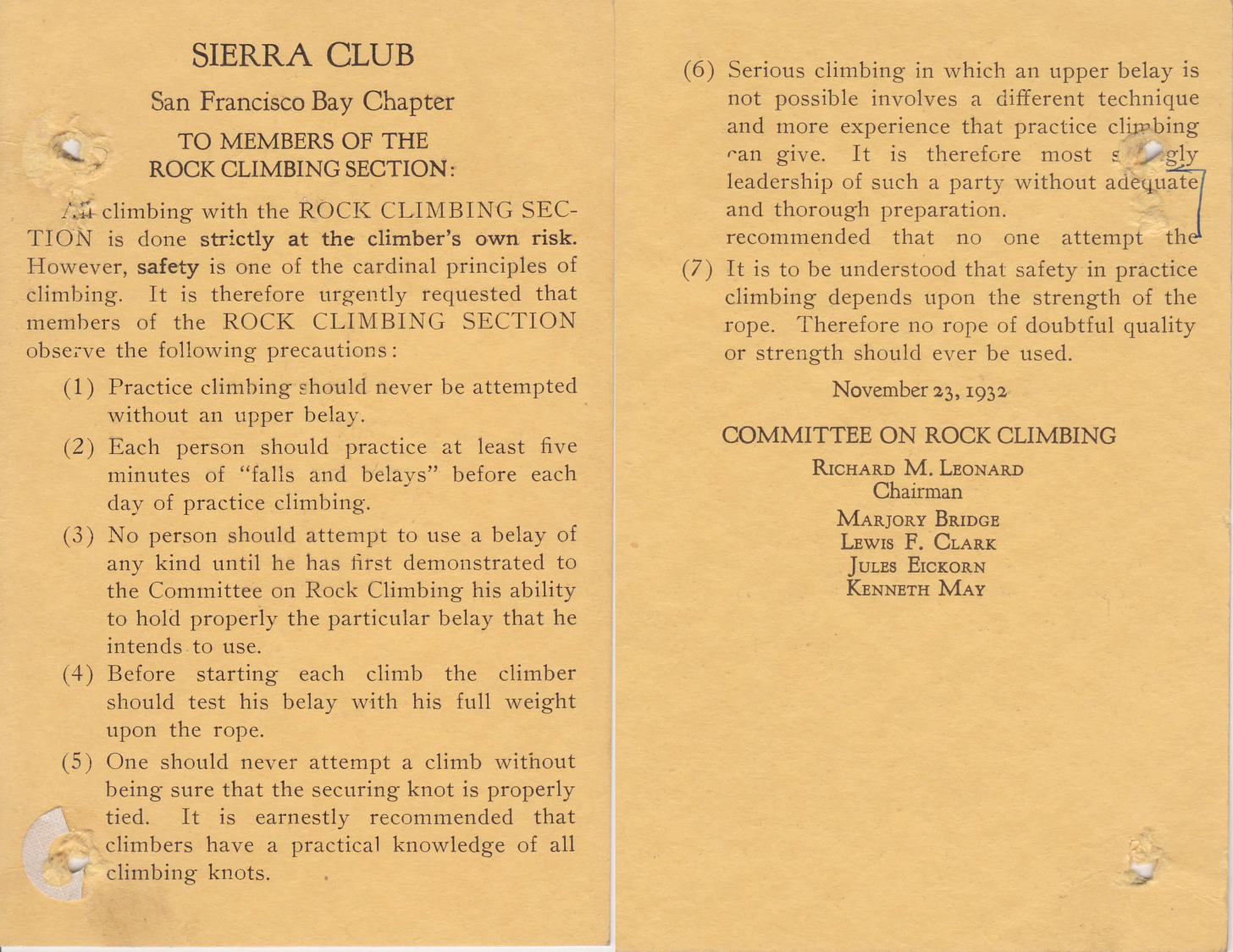

Risk, rules, and shared knowledge

When the bolt was introduced as valid crossover technology from the industrial anchoring and fastening industry, along came the often heated ‘ethical’ arguments regarding the new tool, along with other codes of conduct. As more Rock Climbing Sections (RCS) of various local chapters of the Sierra Club emerged, the rules were strict in terms of safety, led by the original RCS founder, Richard Leonard. FIRST, learn from the network directly, THEN, and only then, venture out on your own. In essence, a qualified training course. But not all tools were widely taught, like the art of hand-drilling a safe bolt into a piece of vertical rock—which the RCS members pioneered—some advanced tools were initially kept close by the cognoscenti. As interest in rock climbing grew, so did the formulation of cultivating a culture around the acceptable methods to ascend varied types and lengths of vertical rock—with a myriad of potential and newly imagined challenges all over the world.

By 1939, the complete set of rock ascending tools was in place:

Protection for natural cracks (thin steel pitons and wood wedges/coins de bois).

Ability to anchor in, and ascend blank rock (expansion bolts).

Efficient anchoring and belay systems with ropes and points of intermediary protection connected by carabiners and importantly, slings—climbers often carried lengths of 8mm cord to connect rope systems, cut up as needed (the need for slings seems to have eluded many early piton/carabiner users, with ample stories of horrendous rope drag, but the use of slings was by now an established tool and technique).

In the periods that follow, refinements of these primary tools became safer, stronger, lighter, more versatile, functional, and convenient. Perhaps most critically for the rapid advancement of climbing standards and achievements, the tools also became increasingly available and more affordable.

For North America’s gigantic canyons and ranges of stone, such as those already explored in Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming, only the surface had been scratched, and more walls were beckoning. Warm climates offered relatively safe environments to develop sporting means of ascent, leading to breakthrough bigwall climbs in Yosemite in the 1940s. At the same time, in the North Cascades in Washington, climbers were pushing new realms of suffering on cold big stones, and all these places became training grounds where American climbers learned the mixed art of cold weather mountaineering and rock climbing on ever bigger climbs.

In this section, we will consider another important part of the “kit” essential for multi-day rock climbs in America: lightweight bivouac and cold-weather survival gear, carried on one’s back or potentially hauled on steep rock.

European Advancements

Consider also the global culture of rock climbing in 1939, prior to the global war that soon followed. The Eastern Europeans had advanced aid climbing techniques to a high art form (see Volume 1), and in France, new realms of vertical challenge in high alpine environments had been well established, advancing from Allain and Leininger’s climb of the north wall of the Dru in 1935, involving technical difficulty on long walls requiring multiple days and nights; climbers were developing not only top-level gymnastic ability but also cold-weather survival and expert glacier and vertical ice skills.

The pace in America

In contrast to Europe, where the market size allowed for the continued creativity of innovators and producers of top-quality equipment, like Pierre Allain in the 1930s, in North America, the development of new tools moved at a more gradual pace. There were clever inventors, but suppliers—those who were able to make batch production of useful gear—were few, and obtaining the latest tools and equipment from Europe posed increasing challenges as the pre-war years unfolded.

In the development of the tools and techniques, it is time to again consider how information was shared among climber groups, and how new tools and techniques became adopted and globally widespread.

Outdoor Leadership

Teachers who share knowledge, especially as it is being developed, often are unsung heroes in the march of progress. The original creators of new knowledge might be too focused on their creative pursuits to share their ideas, or might just want to keep the advantage to themselves. Often, a different mindset is required to navigate the challenging process of transforming ideas into practical products. As tools and techniques became more complicated and varied, the shared knowledge of their efficient safe use naturally emerges.

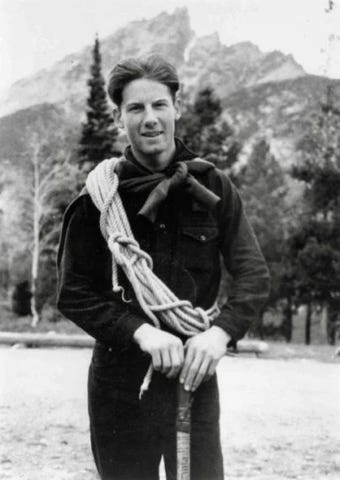

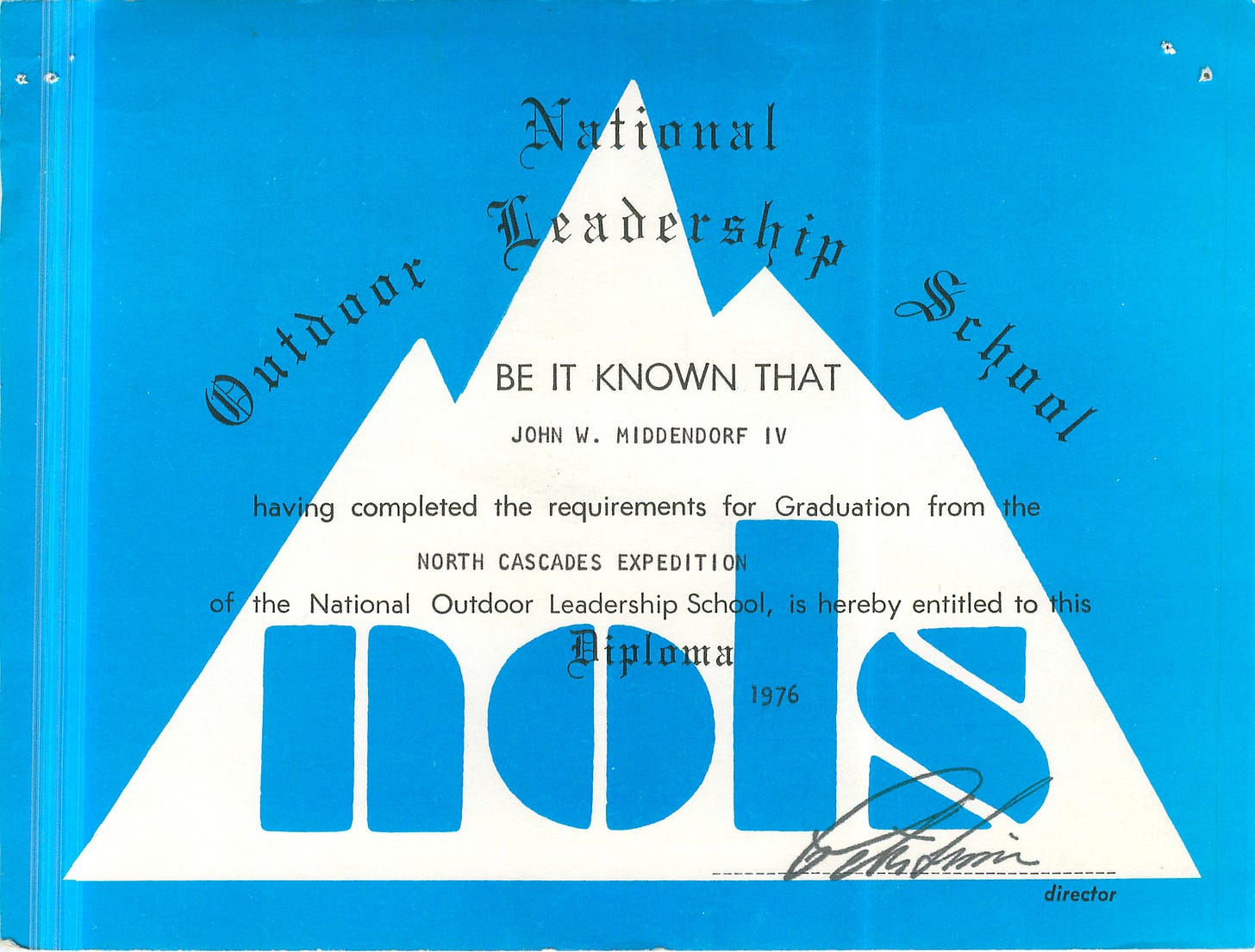

One of the great American educators of climbing and surviving in the mountains was Paul Petzoldt, who as a teenager in 1924, attempted the unclimbed east ridge of the Grand Teton with Ralph Herron, with only an “old hay rope”, cotton shirts and cowboy boots. Halfway up, “lightning flashed like hell and the damnedest downpour you ever saw, with hail and then snow,” and they suffered through a cold bivouac. After retreating and regrouping, the next day they climbed the original Owens-Spalding route, and soon Petzoldt learned the art of cold weather survival and began his guiding business in the Tetons. By 1929 he was awarded the first mountain climbing guiding concession in the newly established Grand Teton National Park, and hired top guides like Jack Durrance. Later in life, he founded the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), which has taught so many the ways of the wilds, as well as the major proponent of sustainable LTS (Leave No Trace), a style distinct from traditional heavy-handed camp skills (e.g. cutting trees for shelter, etc.). By first learning—the hard way—efficient survival techniques using lightweight reliable equipment and food for living in the mountains, Petzoldt shared that knowledge, embarking on a career that transformed mountaineering education and the American guiding profession. As he progressed on his journey, teaching countless fledgling mountaineers the ways of the hills, he also played a key role in the development of a comprehensive lightweight toolkit for expeditionary climbing.

Petzoldt’s ethos of Teton guiding was not just about getting clients up a mountain “sack-of-flour” style, as was the reputation of some guides in European mountain arenas (with its much longer history of professional mountain guiding), but was focused on creating experiences that led to lifelong learning in the wilds (footnote). The nature of the Teton mountain range encouraged this style of cultivating self-sufficiency, as the accessible environment, rising sharply from the Wyoming plains, within a few hours of foot travel, there lies a hostile wild environment that has the potential to quickly kill the unprepared.

Author’s Note: My first climbing experiences were on the Western Slope of Colorado with the Telluride Mountaineering School when I was 14, initially training for the 14,000-foot peaks, then delving into acrobatic rock climbing with mentors like Henry Barber, who climbed with us on the rock climbing week on the cliffs between Silverton and Durango. The Telluride Mountaineering School was the brainchild of Dave Farny, who extended the NOLS philosophy of Paul Petzoldt, and allowed the guides quite a bit of leeway to build toughness in students (once I was suddenly pushed down a 55-degree icy snow slope by the guides who wanted to see if I could self-arrest before hitting the bowl at the bottom—I could. I became a guide there myself in my third summer there, but refrained from pushing any students off precipices.) Later in the 1970s, I completed a NOLS course in the North Cascades, where I further honed my survival and climbing skills. The survival skills I learned in these mountaineering schools saved my life many times on the big rock wall projects of my climbing years, I am certain. A few decades later, on my first visit to the Tetons, I soloed the Owens Spaulding and also became eager to work in the ideal training grounds for leading trips and teaching mountain skills, and soon after worked as a guide for the Jackson Hole Mountain Guides for a couple of summers.

Petzoldt and “campers”

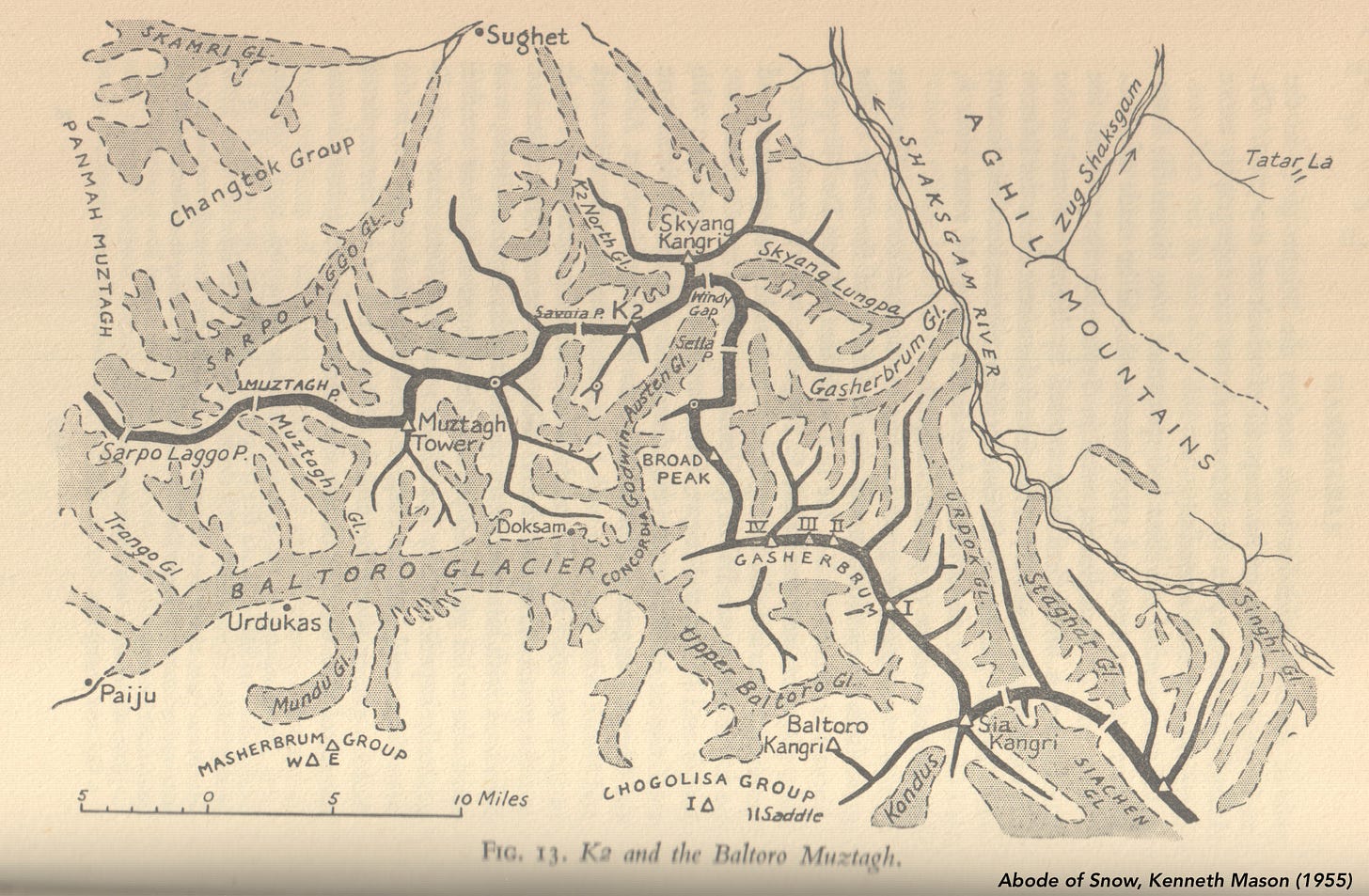

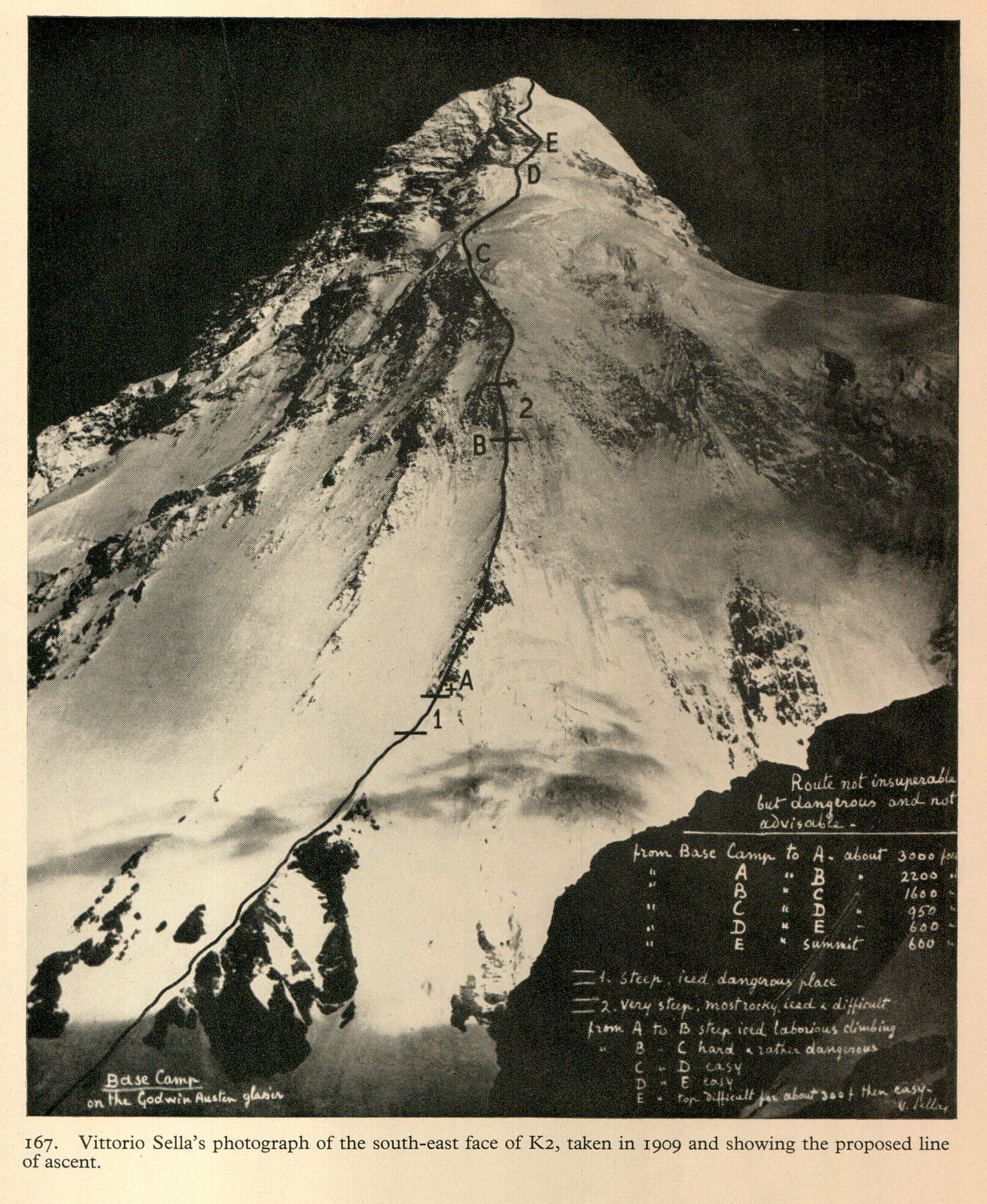

Petzoldt was a member of the first American Expedition to K2 in 1938, and in a later interview and recalled that the lack of “camping skills” among some of the expedition members was the root cause of the failure of the early American expeditions to the Himalayas. “You just have to be a good camper”, Petzold said of the 1938 expedition, “I knew how to camp and I kept the people in line, kept them from getting cold and kept them fed well and kept them from going too fast and over exerting and getting tired and setting the pace and rhythmic breathing and all that thing.” (footnote). He attributed the overall relative lack of American success in the Himalayas to prima donnas who could climb well but lacked “camping” toughness: “They don’t know what the hell they’re doing. And that’s the history of Himalayan climbing. Those guys weren’t campers.”

Footnote: In the 1979 interview published in Off Belay, Petzoldt called his fellow expedition members in 1938 “children on the mountain”; however, the core members had extensive expedition climbing experience (Bob Bates on Mount Luciana in the Yukon, Charlie Houston on Foraker and Nanda Devi, Bill House on Mount Waddington) so this memory was hyperbole. Bill House, who led the notorious “House’s Chimney” on K2 in 1938, a 45m near-vertical and smooth chimney, backed with ice, which required four hours of effort in the thin air of 6700m., joined Houston and Bates in a rebuttal letter signed, “The Children on the Mountain” (February 1980 Off Belay). Petzoldt attributed the tragic death of Dudley Wolfe on K2 in 1939 not to Weissner, Durrance, or Eaton Cromwell, as various attempts to conclusively lay blame on an individual persist, but to the fact that Wolfe wasn’t a good “camper” (“the poor bastard, couldn’t beat his way of a paper bag.”).

Himalayan and Karakoram Equipment Crossover

Of course, good camping skills require good camping equipment. Parallel to the burgeoning sport of rock climbing was the explosion of global interest in climbing the highest points on Earth in the 1930s. The giant remote mountains in the Himalaya and Karakoram demanded larger teams in order to survive communally while traveling through hostile environments, with staged camps and extensive fixed ropes on the mountain, in contrast to the small-team approach of efficient rock climbing. The general developing boom of extreme weather camping equipment, as well as the recreational ski market, inspired the use of new materials and means of production. The advancing state-of-the-art in these realms brought crossover benefits to the rock climbers eyeing ever-bigger walls and considering the challenge of spending multiple days and nights on the vertical.

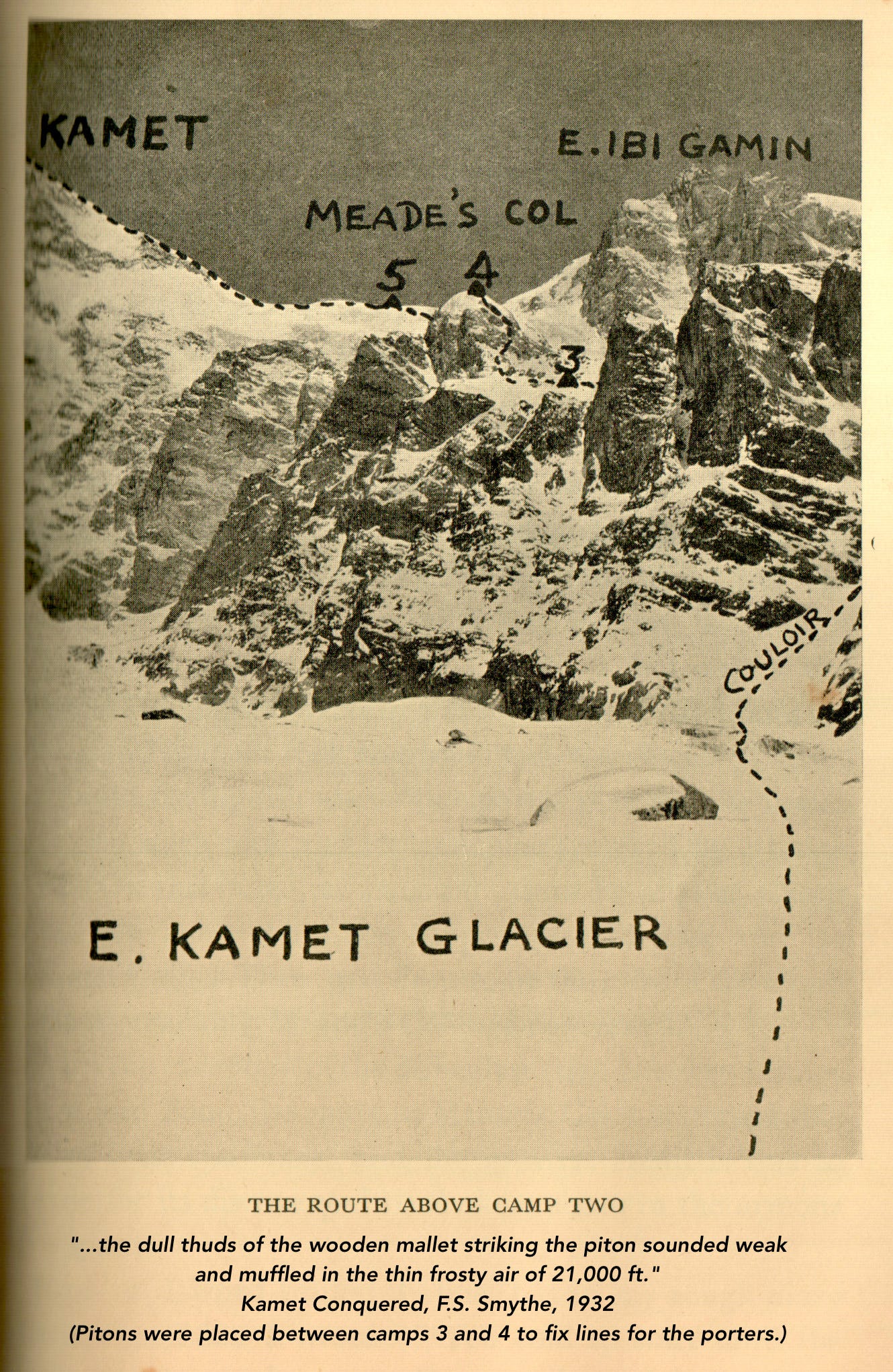

Likewise, the traditional big mountain climbers were adopting the new rock tools even as debates on “artificial aid” continued (footnote). Even the back-of-the-envelope expedition climber Eric Shipton used pitons on Kamet in 1931 (expedition led by Frank Symthe) at 6400m using a lightweight wooden mallet (instead of a metal hammer), in order to fix ropes up a ‘1000-foot rock wall’ above Camp III to create a ‘safe route for laden porters.’

Footnote: artificial aid was pretty much anything besides a rope, crampons, and ice axe—and included supplemental oxygen. Pitons, even if just used for protection, were “artificial”, although the long serrated flat ice pitons developed in the 19th century by Oscar Eckenstein do not seem to be considered artificial aid as they were simply more efficient tools than what an ice axe could provide—perhaps as they made the actual slope less slippery, the ice pitons helped slide the ‘ethics’ toward rock piton adoption (slippery slope joke btw).

In the 19th century, multinational expeditions were common (e.g. British, Austrian, and Swiss members on the team), but by the late 1930s, when India only permitted one expedition organized by a single country per year, the big mountains became regarded as national ‘preserves’: Everest for the British, Kanchenjunga & Nanga Parbat for the German/Austrian teams, and K2 for the Americans (until 1954, when the Italians climbed it). Styles varied, but most were expanding and refining the evolving Himalayan strategy of large teams establishing staged camps and frequent travel between camps to create and stock a high camp for a final assault by a small team. By the 1930s, arguments against pitons in the high mountains had become moot, as the ability to fix, descend and later ascend a rope became intrinsic to the strategy. But on the 1938 American K2 expedition, the leader Charles Houston did not consider pitons necessary, as Petzoldt recalled: “Charlie was an anglophile. He was so anglophiled at that time that he forbade me to bring any pitons or carabiners on the trip. I used practically the last money I had to go into Pierre Allain’s in Paris and buy me a bunch of pitons and carabiners. I had a chance to see some pictures of the mountains, and I wasn’t going up there without any pitons or carabiners. And come to find out, Bill House had done the same damn thing.” It was lucky they did, as the many crux sections to their high point, including House’s Chimney pitch, could hardly have been climbed without them, let alone re-ascended easily to stock the higher camps. In a few decades hence, the use of fixed ropes to ease the final push would become the most controversial technique in the specialized realm of Yosemite bigwall climbing.

Footnote: Charles Houston had been on the successful British/American Nanda Devi expedition in 1936, which put Bill Tilman and Noel Odell on the summit. Tilman and Shipton had attempted Nanda Devi in 1934 as a small ‘lightly laden’ party that included three Sherpas, Ang Tharkay, Pasang Bhutia, and Kusang Namgay (three of the most experienced high-altitude climbers at the time), but the climb turned into a significant reconnaissance primarily due to the ability to travel fast and light (which Shipton/Tilman are best known for) and the discovery of an optimal ascent route on the south ridge, where they reached 6250m (note: back then published measurements were in feet, so the first ascent of Nanda Devi with a height of 25,645' feet (7816m)was a breakthrough “25-thousand-footer’—until the triumph of the metric system and the 14 peaks over 8000m became the modern tick list).

Per usual, this introduction to bivouac gear has gone on much longer than intended, with a few sidetracks, so next we will take a quick look at the 1939 state-of-the-art camping and survival equipment vital to long-term stays in the mountains; tools like tents, backpacks, stoves, lighting, and winter clothing (as well as a brief review of ice gear), so we can better understand how the development of such tools progressed. As Riccardo Cassin wrote in the Alpine Journal in 1972, the continual improvement in tools “extend the limit of difficulty even further and increase safety.”

Next part soon…

Early mountain life…

Radness! Thanks John, got me excited to camp in the vertical this season