Big Wall Bivouacs and "camping" part2a

draft Tools for the Wild Vertical, end of Volume 2

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

TENTS

The topic of tents and fabric structures is vast, and someday I would like to write more on the topic, as I once started a tension fabric structure business, designing double-curvature fabric structures. The structural and anticlastic design concepts of indigenous populations (of note are teepees and bedouin tents) took a very long time to be adopted in the outdoor industry, and most mountaineering shelters until the 1970s were either a tarp or simple covering, or a linear structure that was less effective with wind and snow loadings, albeit with improvements in weatherproofness, ventilation, and temperature control (that were inherent in indigenous designs). So we will not be delving deep into the theory in this volume. Instead, we will mostly consider the state of the art of various mountaineering and camping equipment in the late 1930s—the pre-Nylon equipment days.

Tent Evolution 1800s-1930s

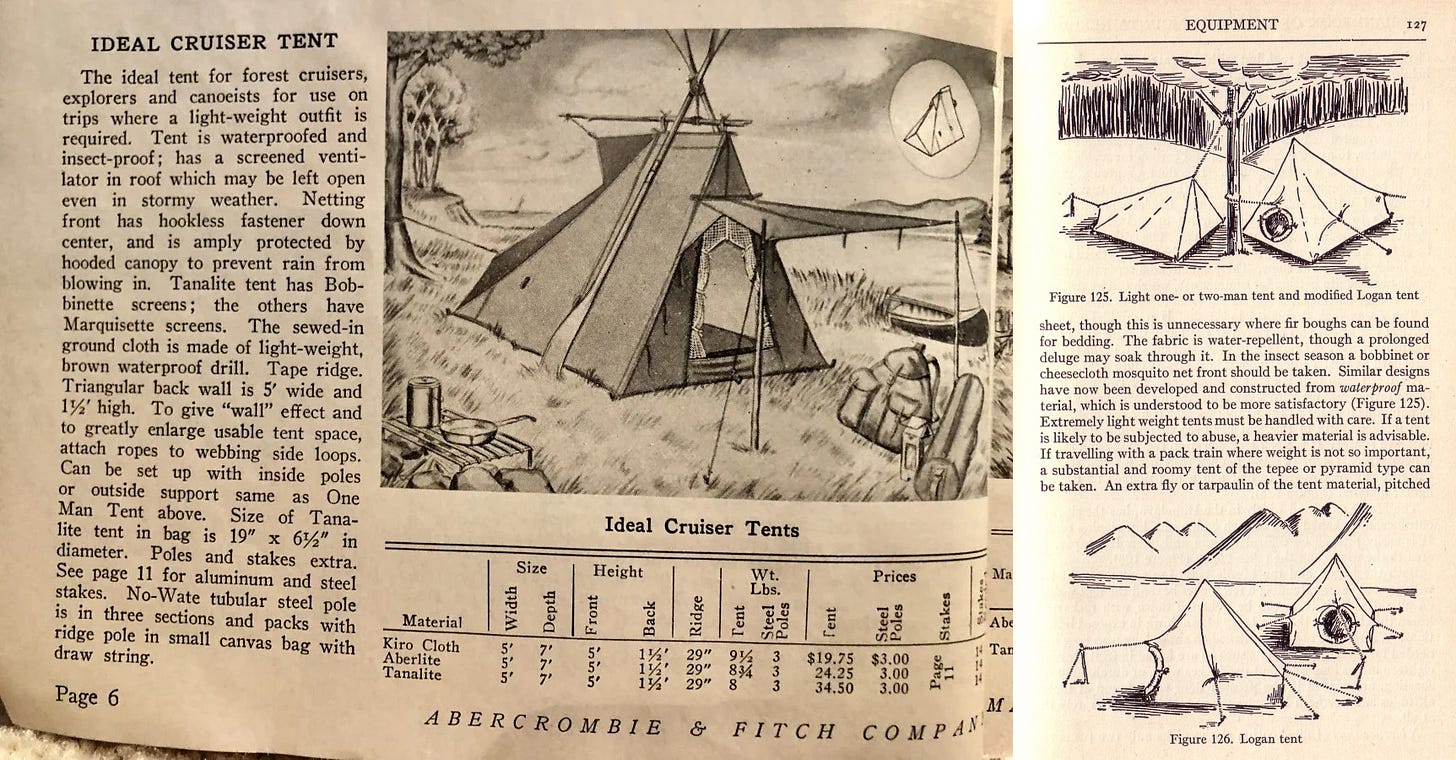

Whymper’s 1865 simple A-Frame tent design was pretty much the state of the art for the first 100 years of modern mountaineering. Various structural and design tweaks evolve with many variants produced with improved openings, vestibules, and later, double skin systems. New fabrics and aluminum structural components were the most significant drivers toward lighter-weight systems.

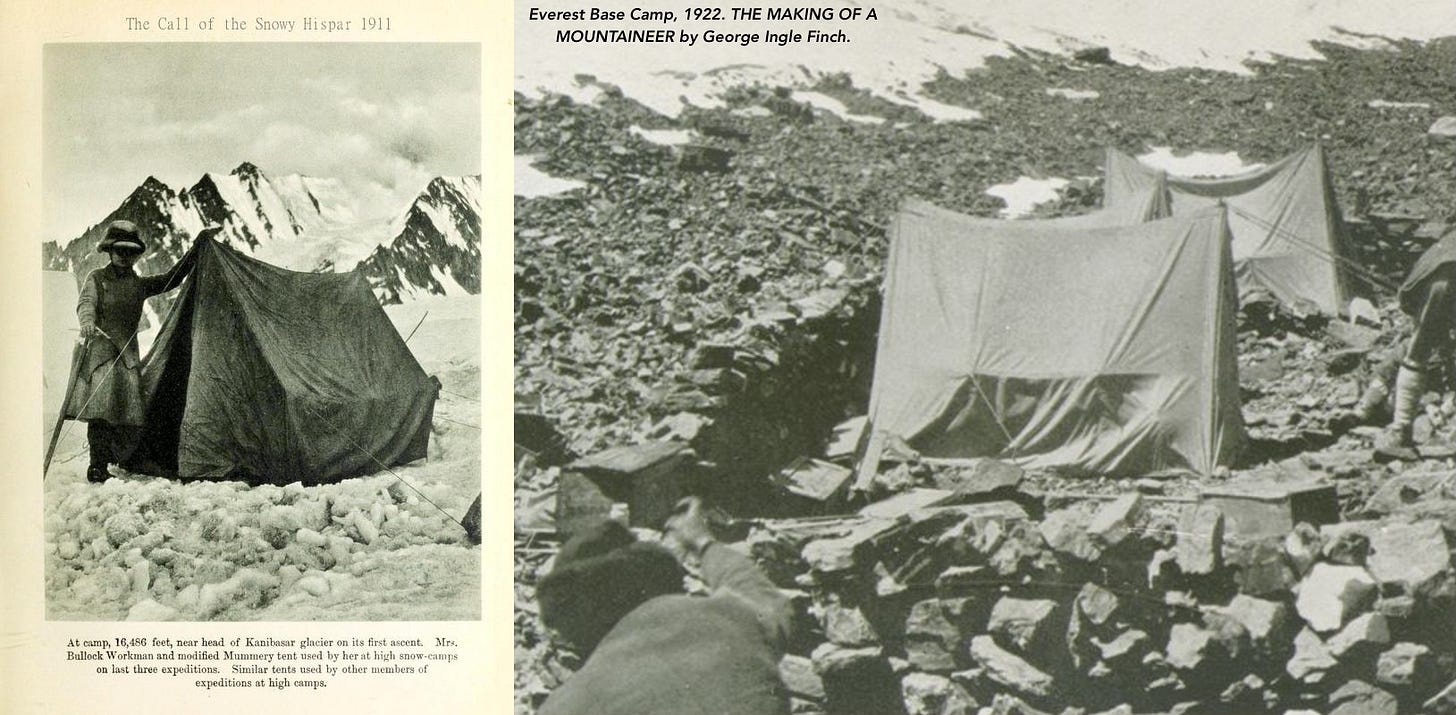

Mummery Tent Design 1890s-1950s

As a way to go as light as possible, the original ‘Mummery tent’, designed by Albert Mummery and used on his fated Nanga Parbat expedition in 1895 (as well as some earlier expeditions) was a floorless tarp/tent, with raised and tensioned sides for additional side-to-side room. The main supports were the long ice axes of the era, used with extenders for the larger versions; when set up properly, the Mummery tent was a suitable 4-season expedition tent design of minimal weight. Initially made from lightweight silk (which would have offered a nice balance between waterproofness and breathability for cold climates), and later from ‘aeronautical’ (balloon) fabrics and other rubberized textiles. Typical two-person tents made of this floorless design and with materials of this period weighed about 2.5kg.

Early variations to the A-frame designs were often awkward, though the single center pole Logan tent offered some significant benefits, mostly in terms of ventilation with its high ceiling if the openings were designed well.

Fabrics 1920s

In the 1920s, new processes for manufacturing expanded the availability of treated cotton fabrics, including paraffin-impregnated canvas fabrics, sometimes called ‘waxed cotton’, a fabric that could be thinly and densely woven to provide both water resistance and breathability. Many specialized weather-resistant lightweight cotton fabrics were developed and branded in this period, with various weaves and impregnated with oil, wax, or other hydrophobic additives, for example, the Grenfell woven twill fabric, advertised as “snowproof, rainproof, and windproof.”

Different fabrics then, as now, had different tradeoffs between weather-proofness and breathability and some of the 1930s cotton-based materials would be competitive with many modern synthetics today. The basic concept is that material itself is made water-resistant and does not absorb water, but due to the porous weave, water under pressure will pass through, though with tighter weaves and heavier impregnation, cotton-based fabrics could be made effectively waterproof. For different conditions, different fabrics were preferred—more breathable (and thus less waterproof) for cold and dry climates where only snow is expected, or more waterproof for wetter climes.

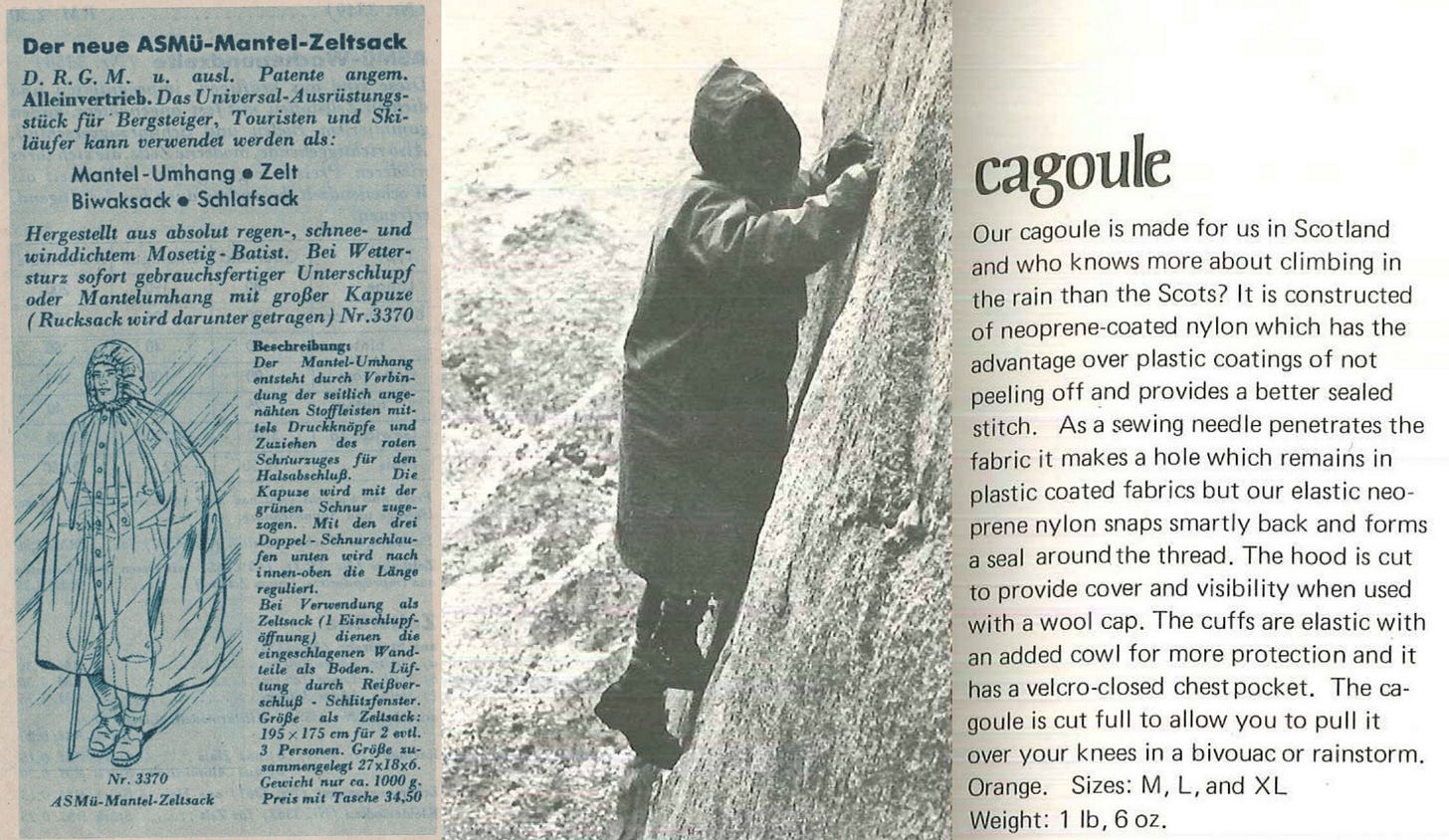

Rubberized fabrics were also manufactured as high-pressure waterproof textiles, and by the 1920s, Goodrich Rubber Co. (Akron, Ohio) and other manufacturers had improved significantly on the Mackintosh-type fabrics, with the ability to durably double-coat fine-thread cotton fabrics with very thin and flexible layers of latex rubber (creating a ‘3-ply’ fabric). One of the lightest, strongest, and most flexible waterproof fabrics of this period used by the outdoor industry, was the ‘Mosetig batiste’, produced for the medical industry “to keep patients dry during operations” (think: similar to those crinkly plasticity pillowcases and bed covers you see in hospitals). The original development of the fabric is attributed to Professor von Mosetig from Vienna, who designed it for surgical operations to prevent bodily fluids from escaping, and it was widely available globally (price: $1.25 per yard in America in 1915).

1930s lightweight tent designs

For alpine and wall climbing, a lightweight tent design known as the “high-touring tent”, a design of Willi Welzenbach, was made by a number of makers. ASMü offered a lightweight version made with their trademark “Himalayan Linen”, a waxed cotton fabric for the walls for breathability, and a fully waterproof material for the floor. The two-person high-touring tent offered in 1937 weighed 2.3kg—an improvement to the prior state-of-the-art in a lightweight fully enclosed weatherproof design that could be set up in tighter spots with its small footprint.

Footnote: the ASMü High Touring Tent cost 63 German marks in 1937—typical two-person tents made from heavier material were twice the weight and half the cost—a time when carabiners were about two for a mark, so the cost for a good lightweight tent was equivalent to the cost of about 100 carabiners.). Note that these 1937 two-person tents only weighed about a kilo more than more modern single-wall expedition two-person tent designs in the 1990s.

The total weight of the lightest weatherproof systems of tents, sleeping bags, and pads for two people in the late 1930s was about 10kg (5kg. per person), not much more than most camp systems for the rest of the 20th century (until the advent of ultra-light materials in recent decades).

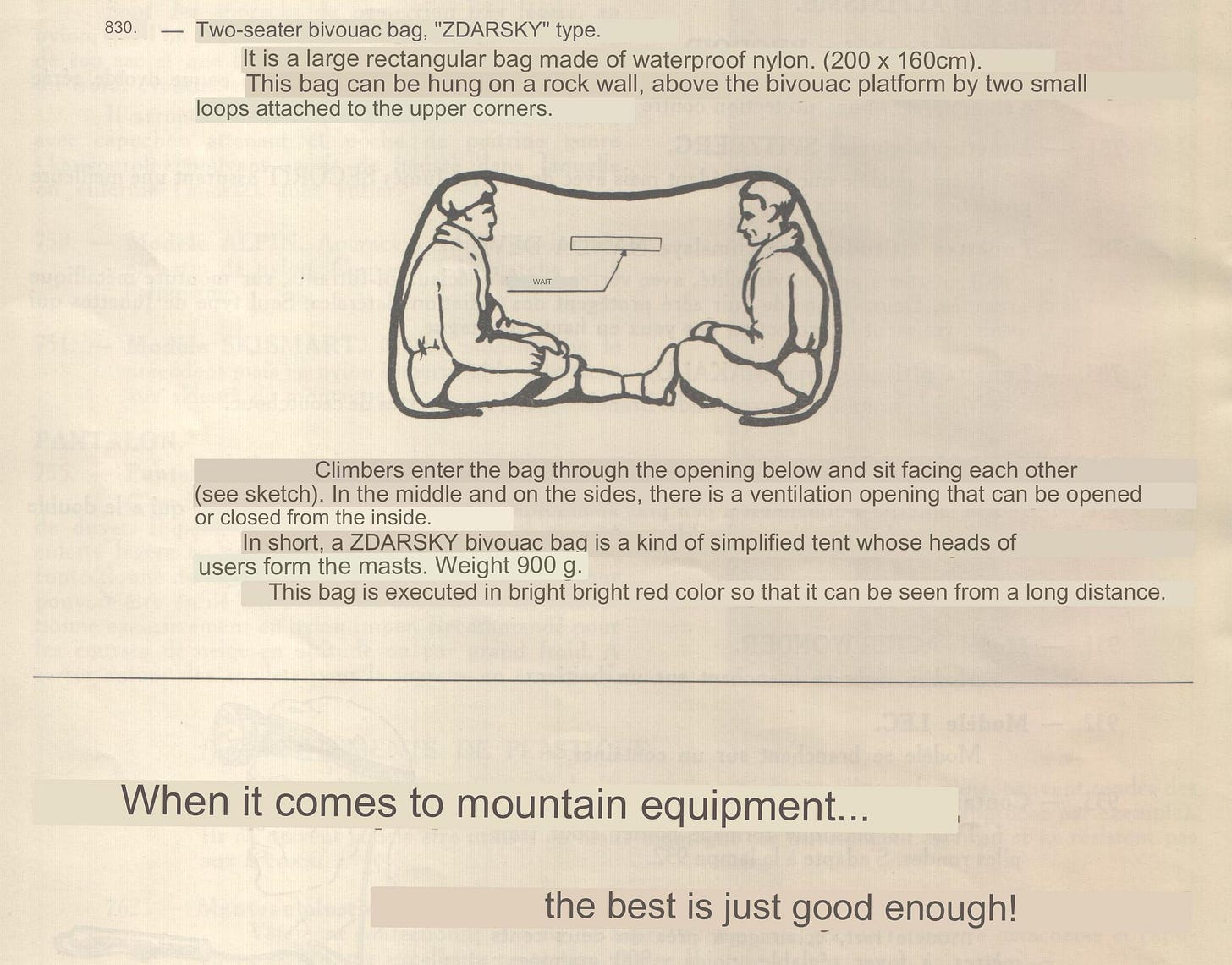

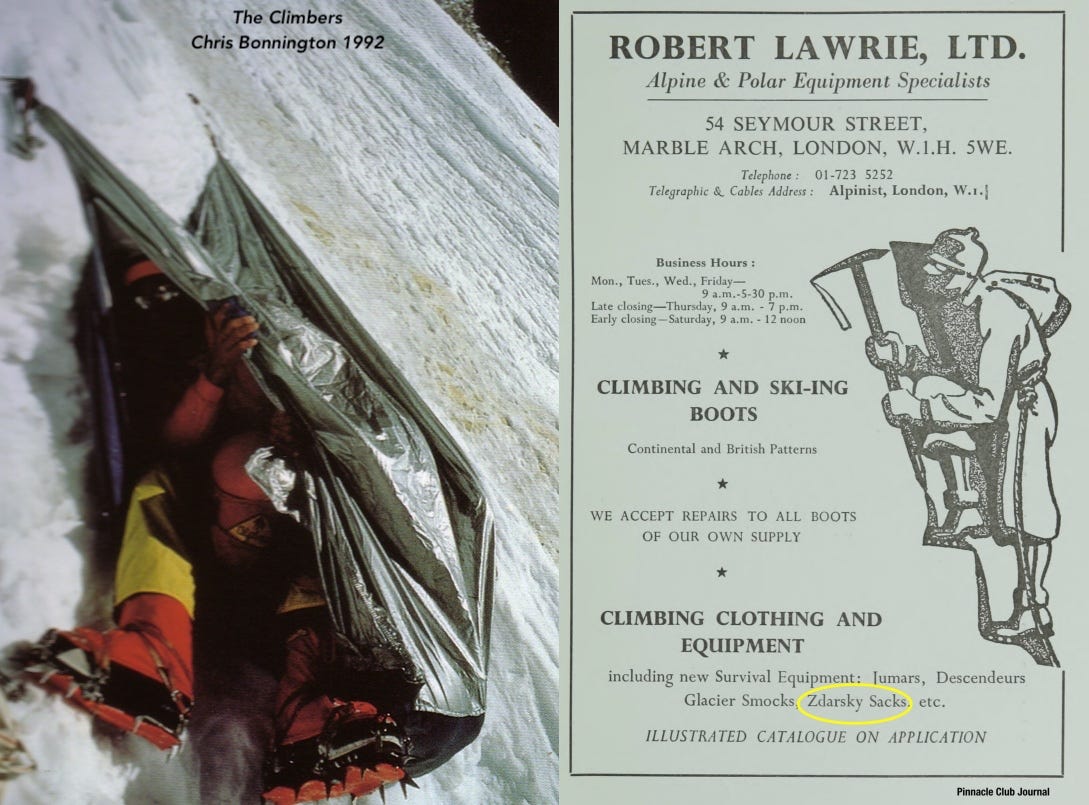

Lighter Bivy Systems—Zdarsky tents

For those wanting to go even lighter, various cliff shelter systems were developed. A popular one during this period was the Zdarsky sack—basically two sheets of fully waterproof fabric sewn together to make a large envelope with an opening on the long side, designed as a group shelter for people to huddle under as a storm passes. Zdarsky was an inventive ski pioneer who developed tools and techniques for skiing, including the single-pole telemark style called the ‘alpine (Lillienfeld) ski technique’. Two attachment points were often sewn into the corners of a Zdarsky tent to suspend it from higher anchors.

The Zdarsky tent is often described in the literature with many variations in size, materials, and the design of the vents and windows. The ASMü 1937 catalog description for the Zdarsky tent reads: “Essential protection against the cold for mountain climbs and bivouacs. Made of thin Mosetig rubber batiste, windproof and waterproof, all seams taped. In sack form with closable vent hole.” Mizzi Langer made a version from a thin rubberised cambric fabric that weighed only 600 grams (200cm long, 135cm width). The 1933 Canadian Alpine Journal describes three sizes: “The Zdarsky bags come in three sizes: 175 cm. high by 200 cm. long (or about 5¼ × 6½ ft.), for 1-2 persons; 175 × 250 cm. (5¼ × 8¼ ft.), for 3-4 persons; and 175 × 300 cm. (5¼ × 9¾ ft.), for 5-6 persons. The weight is from 800 to 1200 gms. (1¾ to 2¾ lbs.) for the three sizes.” The Zdarsky design is primarily used as an overhead shelter while huddled in a small area, and brought along as emergency equipment even on day climbs (e.g. Tami Knight recalls “four of us piled under the envelope-like tent” during an impromptu bivouac while climbing a new route on Mount Munday in 1985). The design also has morphed into a side-opening design that can be securely anchored on steep slopes as a type of two-point hammock, particularly useful still today when a snow ledge can be carved out on long steep alpine routes.

Cagoules and elephant’s feet

In the quest for lightness, many climbers did away with any sort of shelter, resorting to simply bundling up with layers of outerwear for cliff bivouacs. Specialized full-length bivouac sacks were also available but not always ideal for mobility and ensuring a tight line to the anchor, while perched on a small ledge and sitting up all night. A popular outer covering design in the 1930s was called the Sohm’s Tent Coat, basically, a long waterproof poncho noted as a “practical combination of tent, sleeping bag, and raincoat”, and weighing in at about a kilogram. This design quickly morphed into the cagoule, with added arm sleeves, and became a core bivouac system that was still popular in the 1970s (the 1972 Chouinard foamback cagoule pictured had enough room to tuck in the knees while sitting and be completely covered). Emptied packs could be used as extra protection for the legs, and ropes as a ground pad. Pierre Allain came up with an integrated system using a cagoule and a footbag (in lieu of an emptied pack), the half-bivy sack coined the ‘Pied d’élephant’ (elephant’s foot).