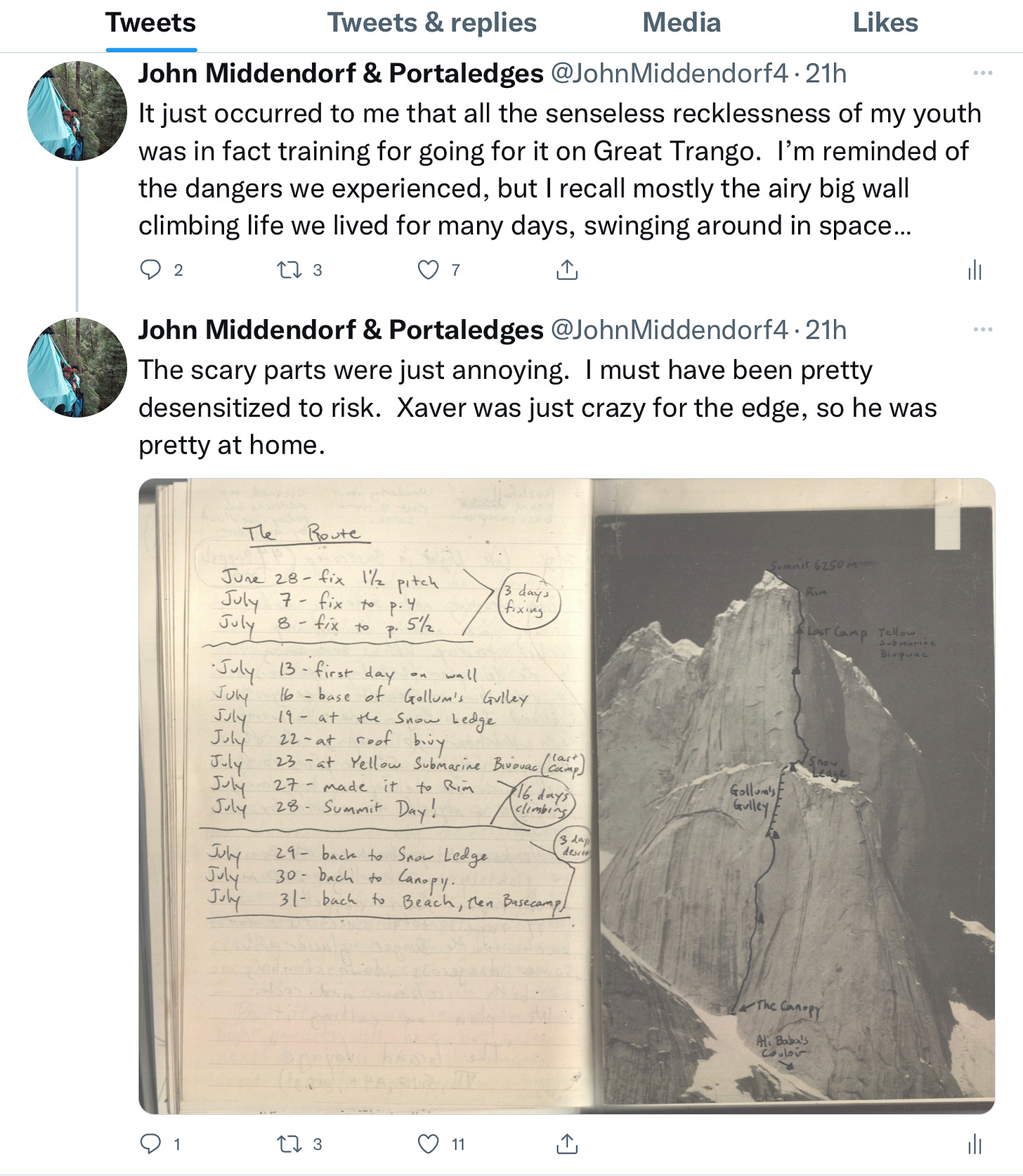

Big Wall Edges

More big wall ramblings and musings, while procrastinating tools research...

I am hearing more about the “edge” lately, I gather it is hitting the mainstream specific to climbing and other “adrenaline extreme sports”. Here are some thoughts of the 1980s edge.

Back in the 1980s, the Camp 4 campfire philosophic musings of “the edge”, often began with discussions of Aldous Huxley’s, The Doors of Perception, which nearly everyone had read or had pondered its ideas. Jim Bridwell is most well-known among the big wall aficionados as the one who pushed for the absolute edge, with experiences sometimes enhanced by psychedelics to find the most intense moment possible. “How would I handle it?” we all asked ourselves.

Some took the engineering approach. Walt Shipley had the famous 3-day plan, which assured a complete rest day, then a warm-up day, then a full-on intense fest, usually involving soloing at about the same maximum grade he could climb with a rope and partner, on climbs he had never seen before with a very spontaneous plan. He would usually return with animated stories, but some of Walt’s solo days out of camp were so intense he would just brood on his own for a few days before being able to share his PTSD of some near-death experience.

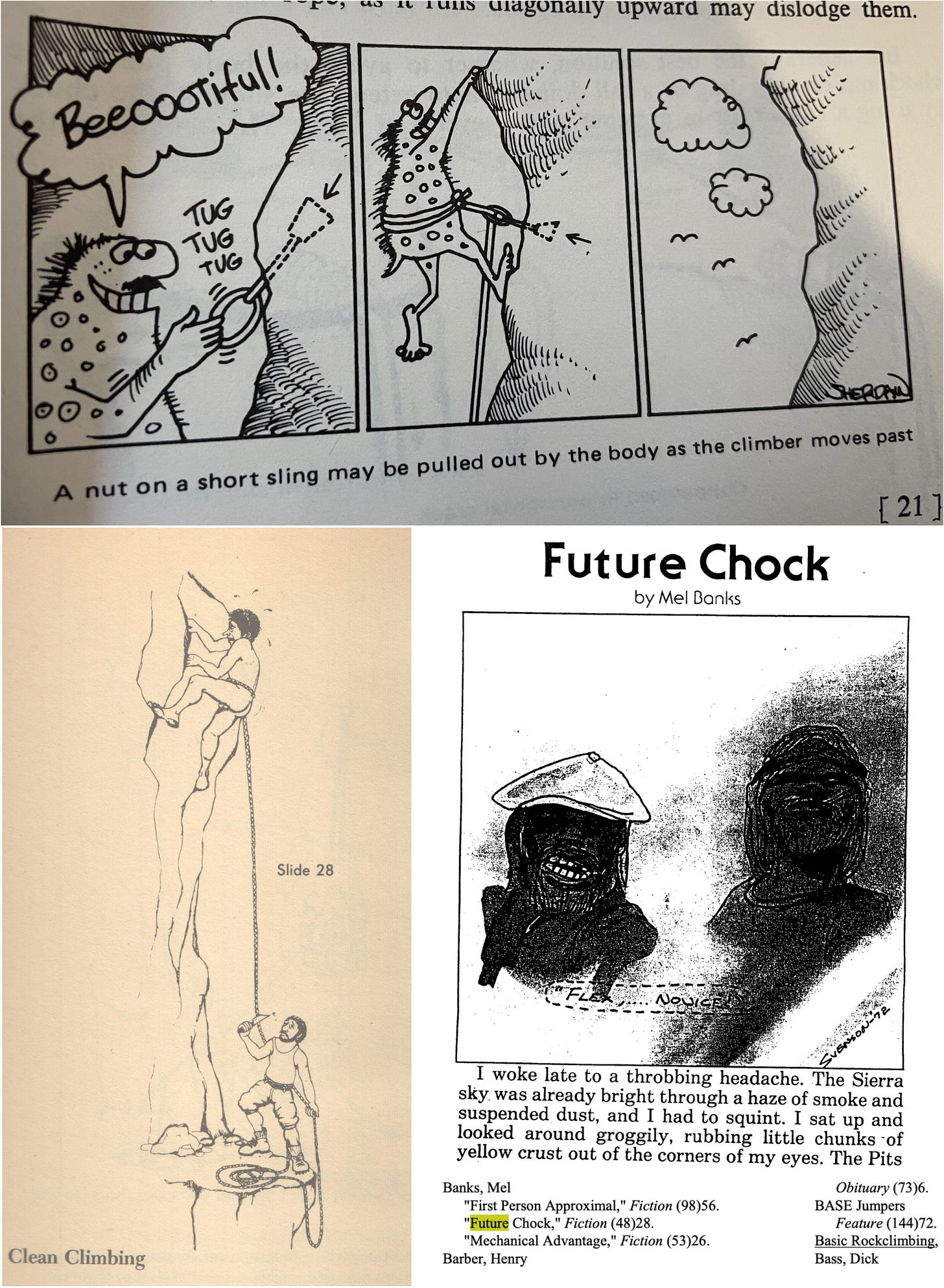

Cartoonists like Sheridan Anderson, Beryl Knauth, and John Svenson captured the zeitgeist well. It was trial by fire, let’s see what you can do —“flex, novice!”. In 1980, the very first day I arrived for the first time in Joshua Tree, Jon Freriks asked me if I liked to solo, sure, and soon found myself all around the Hidden Valley on the most exposed and difficult upclimbs (and downclimbs) that I had ever done without a rope in my life. It was the beginning of a path that I more and more considered worthwhile in the 80s and early 90s, to put my life in risk in exchange for truly intoxicating rewards (footnote). The Californian climbers, with John Bachar as the hero and John Long as the legend-maker, had been developing bold and wild styles with many different “flavors”, for some time. Mike Lechlinski, Mari Gingery, and the Watusi (among many others) also developed revered styles. John Yablonski ("Yabo”) style, on the other hand, with his over-the-edge near-death experiences, all feared but few emulated.

footnote: by the Spring of 1998, Dan Osman surmised correctly that I had “lost my nerve” (but perhaps did not understand my reasons). Daniel Duane, who had been interviewing me at the time for a book, overheard Dan say “john’s lost his nerve” to a few of his novices as I was walking away from the bridge at El Cap Meadow—I think I had just declined a ride on the big rope jump he was setting up on Leaning Tower. The prior rope jump I had done with Dan was the year before, a 400’er over the Grand Canyon (just he and I, in the middle of the night, with Ashantee from Hurricane, Utah watching), and I really did not want or need those kinds of shots of adrenaline anymore (that jump, as well as the initial jumps Scott Burke, Dave Schultz, and I pioneered in the mid-1980s, have stories and interesting evolution). Soon after, I found a new groove going with gravity instead of against it, as an 18’ oar boat river guide for Canyon Explorations for five years on multi-week trips in the Grand Canyon, which had just the right balance of go-for-it and spiritual reward.

Nicknames were more important than real names, as the nickname origin usually told a story (e.g. “Spooner” after the night he spent cuddled with his partner during a fierce storm), and doubled as a way to clarify the pecking order when climbing together—who was up for the hardest challenges? For example, if the “Driver” was climbing with the “Schmutzfink”, who do you think did all the hard leads? (the Schumtzfink was a nice guy, btw). We inherited a 1970s tradition, for example, Sheridan Andreas Mulholland Anderson was occasionally known as “J. Wolffinger the Third”, and Beryl Knauth known as “Beasto”, dubbed by Harding no doubt, who coined many a nickname documented in the appendix of his book, Downward Bound (1975). Variable nicknames were common—in the 1980s, Roy McClenahan had no less than two dozen nicknames. After a good lead, he would always be Cowboy Roy, but if he hadn’t done much in a while, he was just the potato head or the beedwagon (footnote).

footnote: some of Roy’s nicknames: Roy boy, the boy, Roy balls, balls, libido Roy, sugar Roy, the love machine, beed, bidus, beedsauce, beedwagon, side of beef, potatohead, 'tate, that a-hole Roy, hummer, lamoille Royo, 'lem, lem-bott, cowboy, cowboy Roy, and the boy toy of joy. Sorry, Roy! ;) Mussy (Russ Walling) was one of the main nickname generators in the 1980s. I was lucky to get the nickname “deuce” from Grant Hiskes, as Mussy’s were often much less suitable for children. I was often, “Deucey-mama”, but if I just pulled off a hard lead, friends like Shultz and Cosgrove would switch to, “Deucey-daddy”. Generally often just “deuce-mama”, not sure why…

The Edge

Back to “the edge”: we really felt there was an edge worth checking out, the idea was to get as close you could to it without going over. Going over meant you were dead. In contrast to the view portrayed in the film Valley Uprising, climbers like Bridwell, Sutton, and Burton did not routinely drop acid and go climbing, rather it was a selective process and depended on the actual challenge and the team. In the 1980s, perhaps, it was more following the ideas in Carlos Castenada’s writings—at first, an external enhancement might be used to open the door to the edge, so as to increase one’s knowledge of where the edge most likely was. Not everyone used external enhancements, of course, but everyone had some way to find their own path, followed by a more studied approach, weighing skills and luck, to planning an adventure that would push one’s own limits, one that required a steady mind to prevent “arcing”, as we called it (as if electrodes were arcing between brain lobes, when the fear and adrenaline threatened performance). Fear was not feared, but rather the maximum level of control while in the state of fear was the goal (converting fear into energy is how I always thought of it).

I will write more about the risks climbers were willing to experience using the tools and technologies of the 1980s, but thought I would get some of this background info down first. This kind of high-risk climbing is still around, it is just not as often in the mainstream, and today’s approach is more measured and practiced, and often based on a much higher skillset than what we had in the 1980s. I am interested to see how these concepts build in the mainstream media.

Please feel free to add to this thread in the comments below. I hope also to share long-going discussions on these topics with friends like Derek Hersey, who sadly found his edge during a string of long onsight solos in Yosemite, and was well aware of the dangers involved with his pursuits while taking it just a bit farther than anyone else at the time.

to be continued….

Some relevant tidbits from Supertopo:

More Nicknames (warning, not suitable for children)

The 1980's. The missing history

Camp 4 parking lot (sorry, all pictures were removed at some point)

“prediction” of the first El Cap Solo:

good article by Roy about Ray Olsen (Frog)

Future Chock by Mel Banks

Scared Silly, a story of getting too close to the edge.

Didn't think Aussies were prone to such nostalgia. Quite comforting.......

THE EDGE

MIyamoto Musashi said it all, a while ago: "Gallop your horse along the edge of your sharpened blade....don't stumble, don't dither.

Some people think the samurai were suicidal fanatics but they valued Life greatly. They truly respected honor, commitment and skill. They had no respect at all for sloppiness or substituting suicidal blunder for competence.

When I solo, the Edge I'm searching for is not a near-death experience but a freedom where I am totally enjoying the experience. I dislike even the whiff of fear and see no merit in seeking it out. Enough of that comes along in any case. Better to look for the Holy Grail of Joy, Exhilaration, Rapture, Fun.

Rhodesian mores were very quaint and old fashioned -- a result of being tucked away in a far corner of the British Empire. We had no time for recreational drugs, although dagga (marijuana) was cultivated all around by the natives, whom we were trying to help along to a Better Life. Beer was OK.

Consequently, the drug culture in The Modern World always seemed a bit decadent; a cheating short-cut that discounted the true value of The Quest. Why adulterate a fine wine!

And so, the Samurai Way seemed to follow a purer and more noble path. That's the way I read "Journey to Ixtlan".

Great, even grandiose sentiments. They have provided many happy moments.........and moments of sheer terror when the theory went wrong and the shit hit the fan.

In other words, risk was more reckless in those days.