Climbing Tools and Techniques—early North American Developments to 1910

Mechanical Advantage series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Background

Prior to European incursions, Indigenous mountain climbers had summited many of the prominent peaks in the mountains of North and South America, traversed trade routes of notable vertical difficulty through the Grand Canyon, and perched safe homes on precarious cliffs, accessible only via exposed rock climbing. Many of the highest summits in the ‘Rocky Mountains’, first named in Morse’s American Geography (1794), had been climbed prior to white settlement (Bueler, 2000). In the American Southwest, bold technical climbs—both free and aid—had been done by the Hisatsinom, Freemont, Mogollon, Hohokam, Acoma, and many other peoples for over a thousand years. On the steep sandstone tower and cliffs, the ancient’s level of difficulty was on par with rock climbing standards up to the advent of modern mechanical tools, as many explorers have discovered and documented, after following unmarked paths then surprised and amazed by the signs of occupation and visitation of a prior epoch.

Footnote: I have spent many years wandering around the American Southwest from 1986-2008, often solo, in search of the ‘unknown’, to often find it. The boldness of Indigenous climbers is stunning, even as a 5.11+ climber and B1+ high boulderer, I was often amazed by the wild established routes, especially through the Grand Canyon (some were 5.10xx). A good read of the area by David Roberts, “The Lost World of the Old Ones” captures some of the magic. Many guidebooks have now been written, and many of the most beautiful spots are too crowded now. A more recent family trip and Hopi friends, finding some adventure still (2018): 1 2.

Science and Mapping Surveys of the West

With most of the oceans mapped by the late 1700s by the Europeans, scientists began to explore inland for new data, often to the loftiest summits, in search for global patterns of Earth’s systems; in the “new lands” recently discovered by Europeans, early mountain climbing pursuits in the Americas, as on the other continents, were often scientific expeditions.

But as immigrants tenanted the American west, the need to map and partition land prompted early government or commercially sponsored inland survey expeditions, such as the ones led by Alexander Mackenzie (1792), Simon Fraser (1805), and David Thompson (1807) in Canada, and further south by Clarence King, Ferdinand Hayden, John Wesley Powell, and George Wheeler in the mid-1800s. These surveys generally followed the paths of the Native Americans, which had also been known to early trappers and miners, and precisely mapped the terrain in respect to the Greenwich meridian, which became the basis for international and national treaties. Many of these expeditions had an adventurous spirit beyond the requirements of their missions and made technical ascents of summits with rudimentary rope safety systems and occasional spikes hammered into the rock.

In the period oft coined as the “modern era of mountaineering,” when climbing for sport and the pursuit of mountain “conquests” became popular, recent arrivals to North America were also game to join the fun on the new terrain (footnote). Epic tales and maps of explorations around the globe and to the poles were widely read in newspapers and journals, and so it was with the first ascents of the highest mountains, which were then often (re)named, reported and celebrated worldwide. By the late 1800s, the legend of Whymper’s ascent of the Matterhorn with ice axes and (broken) ropes was common lore, though little was known of the more systematic lightweight approaches developing in the Eastern Alps for steep rock.

Footnote: With climbing’s chance for local and international renown, along with this era came the controversies and arguments as to the “first ascent”, cumulating in later debates such as the first ascents of the Grand Teton and Denali, though others gave credit where credit was due: “Above us but thirty feet rose a crest, beyond which we saw nothing. I dared not think it the summit till we stood there and Mount Whitney was under our feet. Close beside us a small mound of rock was piled upon the peak, and solidly built into it an Indian arrow-shaft, pointing due west. I hung my barometer from the mound of our Indian predecessor, nor did I grudge his hunter pride the honor of first finding that one pathway to the summit of the United States, fifteen thousand feet above two oceans.” (Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada, Clarence King, 1871 on the “false” Mt. Whitney).

The early days of rock climbing in North America

The routes to the technical summits of Tu-Tok-A-Nu-La/Half Dome in Yosemite (1875) and Bear Lodge/Devil’s Tower (1893), covered previously, were engineered by the first summiteers, and involved construction tools and materials to create an established path with ladders and fixed ropes that could be followed by others. But as climbers eyed the rocky peaks from the Appalachia to the Sierra, lightweight rope and anchor systems were gradually evolved for the vertical challenges.

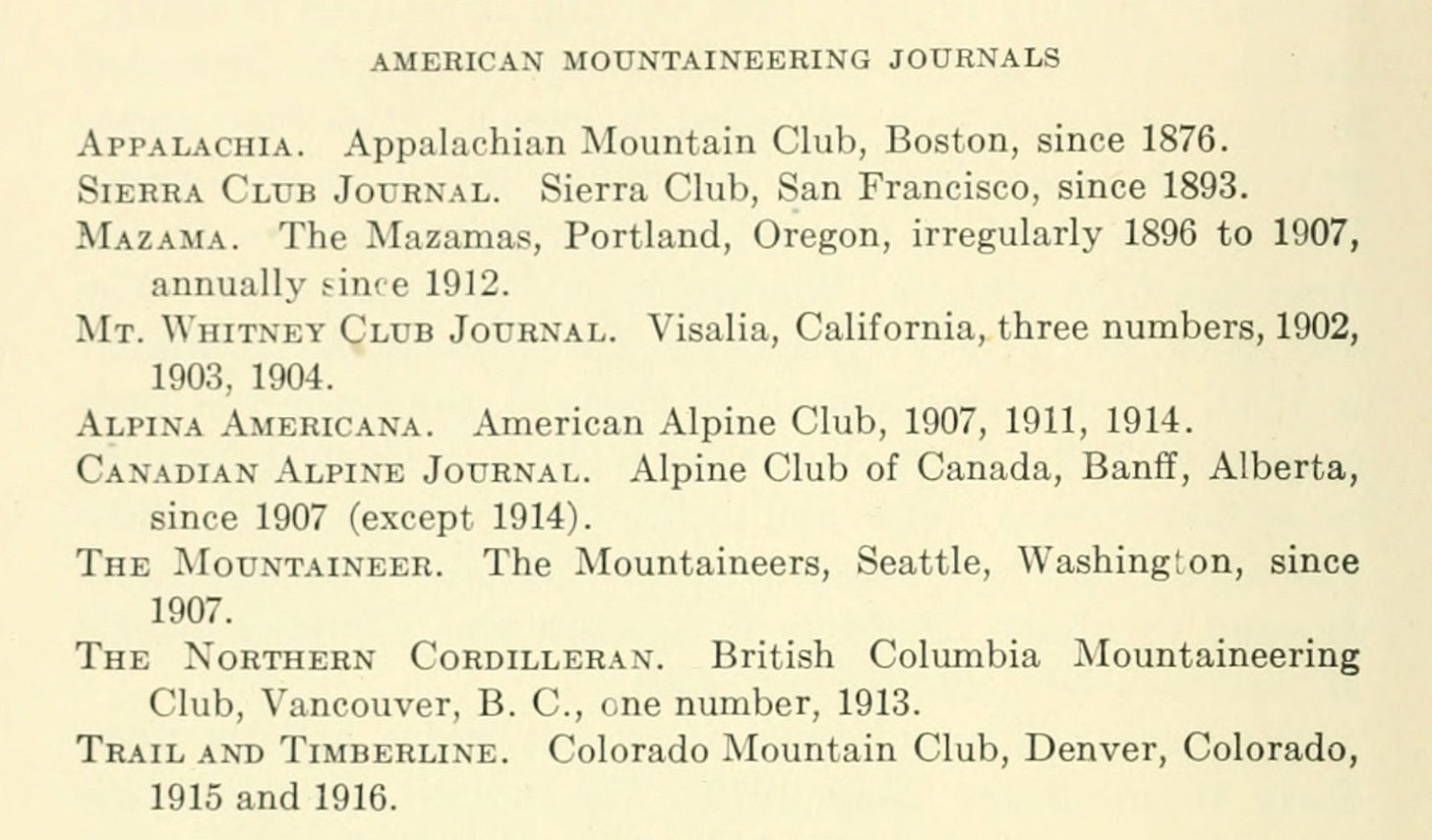

One of the first rock climbing epicenters in North America was the Adirondacks in the eastern USA, with rock climbs dating back to the mid-1800s by those pursuing “spiritual uplift” in the mountains for sport (Fay, 1910), often prompted by the naturalist writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. The Appalachian Mountain Club, one of the earliest North American clubs, modeled itself after the mountain associations in Europe to provide access and huts in remote mountainous regions (footnote). Its magazine Appalachia was the only mountaineering journal in America from 1876-1893. As the sport blossomed in the late 1800s, Appalachia was followed by the Sierra Club Bulletin (San Francisco) in 1893, the Mazama (Portland) in 1896, and later by The Mountaineer (Seattle) and the Canadian Alpine Club Journal in 1907. The American Alpine Club was founded in 1902, and in 1907 published its first Alpina Americana on the High Sierra (by Joseph N. LeConte, followed by Charles E. Fay on the Canadian Rocky Mountains in 1911 and Alfred H. Brooks on Alaska in 1914). In addition to these organizations, there were dozens more smaller clubs that gathered throughout North America to discuss and plan climbing trips. Though membership was generally local, many club periodicals covered global developments, and along with invitations shared among clubs to join each other’s “excursions”, rivalries also soon began for recognized “unclimbed testpieces”.

Footnote: Charles E. Fay, professor of Modern Languages at Tufts College in Massachusetts, describes the founding of the Appalachian Mountain Club, noting that several clubs, including the “little Alpine Club” preceded it, but were “fated to a brief existence and passed with dissociation of the groups creating them". Fay precided over meetings of the Appalachian Mountain Club for over 25 years, before becoming elected as the first president of the Amerian Alpine Club in 1902 (Source: Appalachia, vol 14, 1916-1919).

Sugar Loaf, 1889

Despite the fact that there was an easy way to the summit, an unknown yet intrepid climber drilled safety anchors for a scenic climb up the west wall of Sugar Loaf in the Adirondacks, a climb reported in 1889 as an airy traverse along a cliff “furnished with iron pins sunk in the rock at the most difficult points. A single false step on this path would hurl the incautious climber to instant destruction.” Ropes were recommended. The original description reads, “On the west there are dangerous precipices, and it is on this side that the guide-book describes the ascent. The route via the "iron pins sunk in the rock” is one made some years ago by an adventurous climber of the neighborhood who wished to ascend Sugar Loaf on its only dangerous side, and adopted this expedient to accomplish his purpose.” (Appalachia Vol 5, and A Guide to the White Mountains, Sweetser, 1891).

Mt. King, 1896

In 1896, on a solo ascent of the striking Mt. King (now Mount Clarence King in Kings Canyon National Park), Bolton Coit Brown, a well known New York painter and printmaker (and later director of Stanford’s art school), reports jamming a thrown knot in a crack to overcome “a smooth-faced precipice,” not possible to climb “unaided". He used this technique repeatedly, as well as stepping through a makeshift rope aider to overcome a final steep section of one of Sierra’s first documented crack climbs (Sierra Club Bulletin, Wanderings in the High Sierra, 1897/99).

Grand Teton 1898

In contrast to Half Dome and Devil’s Tower ascents, the highest summit of the Three Tetons in Wyoming involved a more alpine approach. On the first documented ascent of the Grand Teton, rudimentary rope safety techniques were employed, with one person leading, while the rest of the team stood fast, paying out the rope. This technique was already being refined to an art on steep rock in Britain, using natural anchors at places where it was possible to tie the rope into a horn of rock—often called “belay pins”—and sometimes two-person belays were recommended, with one person mid-pitch, perhaps in a more precarious position to assist the leader, while the main belayer had a firm position.

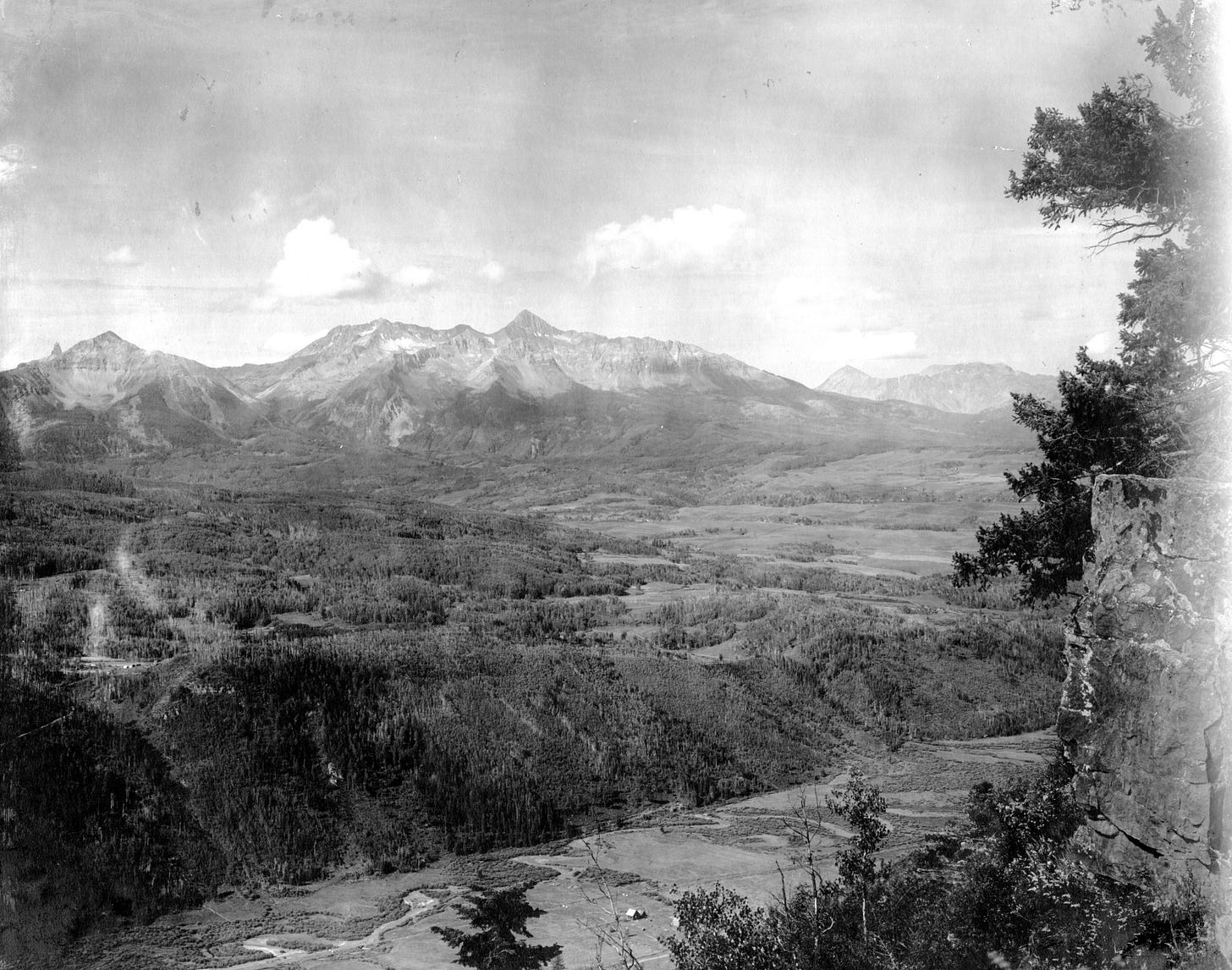

On the Grand Teton, the highest summit of the Teewinots (the Shoshone term for the range), Indigenous people had previously climbed to a small perch on an airy saddle, only a few rope lengths (600’) of steep rock from the summit, and had built a structure known as the “Enclosure.” On August 11, 1898, after eleven hours of climbing, a team under the auspices of the Rocky Mountain Club, led by the experienced mountaineer Franklin Spalding, and organized by William Owen (who had made three prior attempts), made it to the Enclosure from their camp several miles away. Then, with sturdy rock and ice climbing ability, careful route-finding involving an exposed “squirm” along a narrow ledge, and the use of the rope lassoed over a horn to pull themselves up, the team discovered a climbable route up the final steep cliffs to the summit.

Spalding writes: “Our outfit consisted of 450 ft. of rope, two ice axes, two iron-pointed prods, a half dozen steel drills and twenty iron pegs. We made the top, however, without having to use the drills or pegs.” (footnote). The ropes were used for safety and “roping down” in four places; two days later, the team returned for a quicker second ascent to establish “a monument on the summit that should be visible to settlers in Jackson’s Hole, and thereby verify our ascent” (William Owen, The Alpine Journal, 1899). Despite the preparation and inclusion of rudimentary pitons in their kit for the climb, it was several decades before mechanical tools were next employed for the challenges of the Tetons.

Footnote: Spalding quote from Denver Evening Post, August 17, 1898 as reported in AAJ, 1939. Renny Jackson writes, “Owen was prepared to drill his way up and fortunately they didn't have to. They did drill one hole at their campsite in a large boulder and pounded one of those heavy eyebolt pitons in it and it is there to this day. Twenty other pins were found by Ortenburger in the seventies beneath this same boulder.” The same kind of bolt was placed high up on the mountain in Stettner’s Couloir, perhaps placed on a previous attempt by Owen. (See also Grand Ascent, Peter Boutin, 2021, and thanks to Christian Beckwith for additional info).

Technique

In the hearty tradition of American ingenuity, most climbing equipment—ropes spikes, and other tools to create dugways and blast wagon tracks—was improvised, often cleverly, from other industries. Technical summits like the Grand Teton (5.4) were an anomaly at the time, as the much greater focus in this period was on climbing safely on the bigger mountains which primarily required snow and ice skills. In 1905, in one of the earliest articles on technique in the Mazama, John Cameron asks, “Shall American climbers adopt European methods?” The article recommends that Americans, “who are mostly right” and are “nothing if not original”, to adopt the European style of climbing with experienced guides, one in front and one in back, and no more than six climbers roped together, at least ten feet apart, and with each individual “provided with an ice axe.” He laments a recent accident on Mount Ranier and that the “regular Swiss mountain axe” is not readily available from American firms (footnote). Indeed, better equipment and more detailed sharing of knowledge of climbing safely with rope and anchor systems took another decade to filter into North America.

Footnote: In response to Cameron's hint towards a regulated climbing as was current at the time in Switzerland, involving peak fees and the requirement of climbing with guides, the Mazama president, C.H. Sholes responds, "The great charm of mountain-climbing in America … is the fact that the mountains are free to those who seek to derive from them the joy of unaided conquest. Many of them are so free from danger that a person of slight experience in mountaineering can scale them to their utmost summits. Personally, I should regret to see that time come when there shall be guides on our mountains, under State regulation, with the right to prohibit persons from attempting the ascent of any mountain without the service of a guide. If the present interest in mountain-climbing continues (and there is no reason why it should not increase rather than diminish), there will soon be throughout the Pacific Coast region a large number of skilled mountaineers, capable of acting as guides to any mountain in these ranges.” Prophetic words, indeed.

Information Sharing

At the time, shared knowledge of climbing tools and techniques filtered slowly from Europe, and English language books such as Clinton Dent’s Mountaineering (Badminton Library, 1892), Claude Wilson’s Mountaineering (1893, price two shillings), and George Abraham’s The Complete Mountaineer (1908) were light on “artificial” techniques such as safety anchors. Even well into the 1920s, the only pitons depicted in English language literature were the very heavy eye-bolt round spikes similar to those used for trail building, and impractical for lightweight mountaineering. That would change dramatically in the early 1930s in the United States and Canada, but in the meantime, the improvisation continued.

Although there are occasional references to pitons as iron pins, spikes, stanchions, or eyebolts in climbing contexts (or, for example, as a way to lower wagons down cliffs as the Mormons had done to get to Bluff on the Hole-in-the-rock expedition in 1879), as it was in England, Canada, and New Zealand at the time, if pitons were used in the late 19th/early 20th century for early rock climbing, few were reporting or admitting it. Rock climbing had been advancing steadily, but climbing vertical rock was an adjunct distinct from mountaineering, as most mountains had alternate paths to the summit that did not require gymnastic steep climbing skills. In the tradition of The Night Climbers of Cambridge, by 1900, British climbers were solo free climbing at a high onsight standard, on buildings but also on the varied rock of the British Isles.

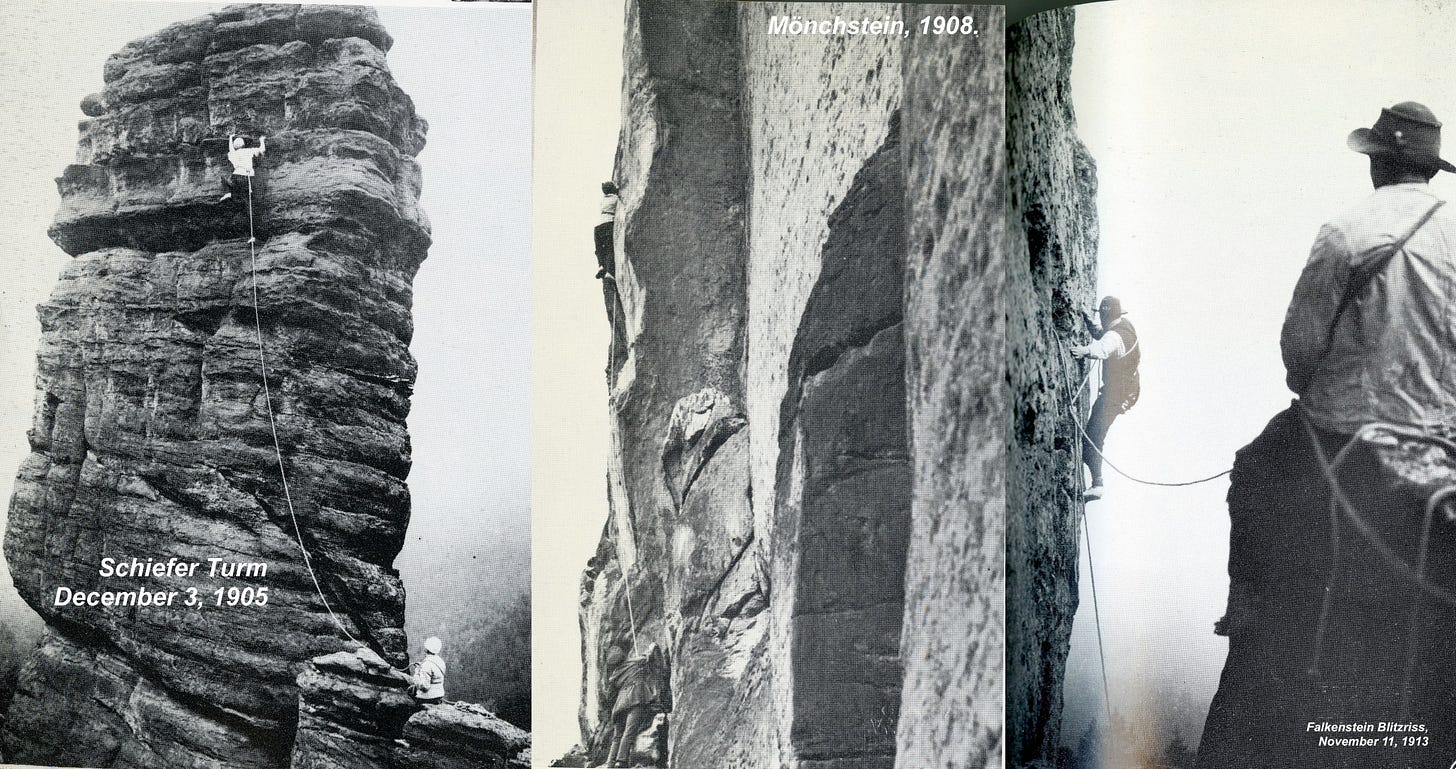

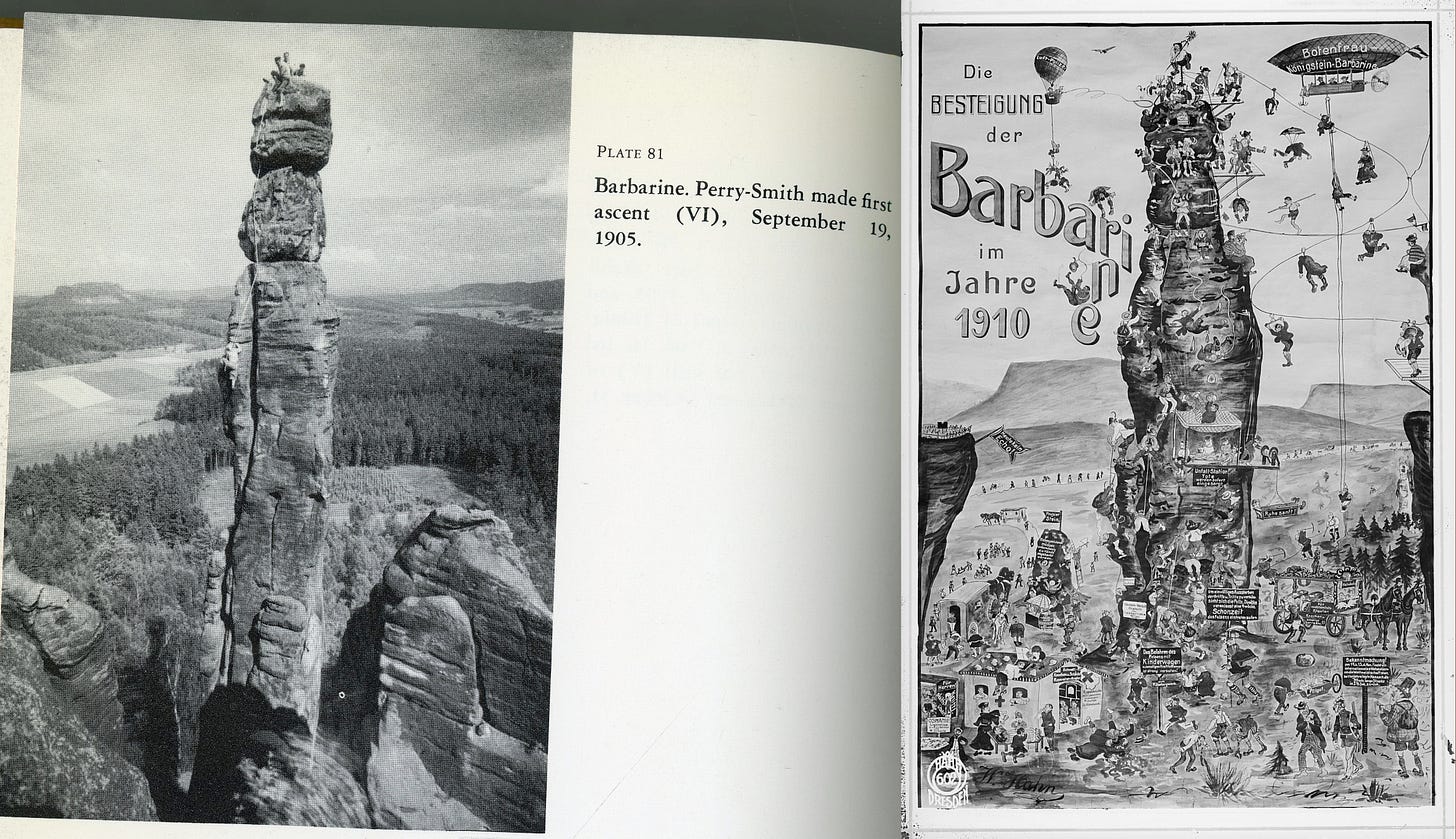

In terms of bold gymnastic ability on rock, the standard of free climbing with carefully thought out mechanical protection, the level of technical rock climbing in the Elbsandsteingebirge was beyond anything done in the major ranges for many decades, often incorporating complex acro-yoga type teamwork maneuvers. The history of the region pre-dates any other competitive sports arena in climbing, with pioneer Oscar Schuster’s adventures documented in his diaries (Tagebüchern).

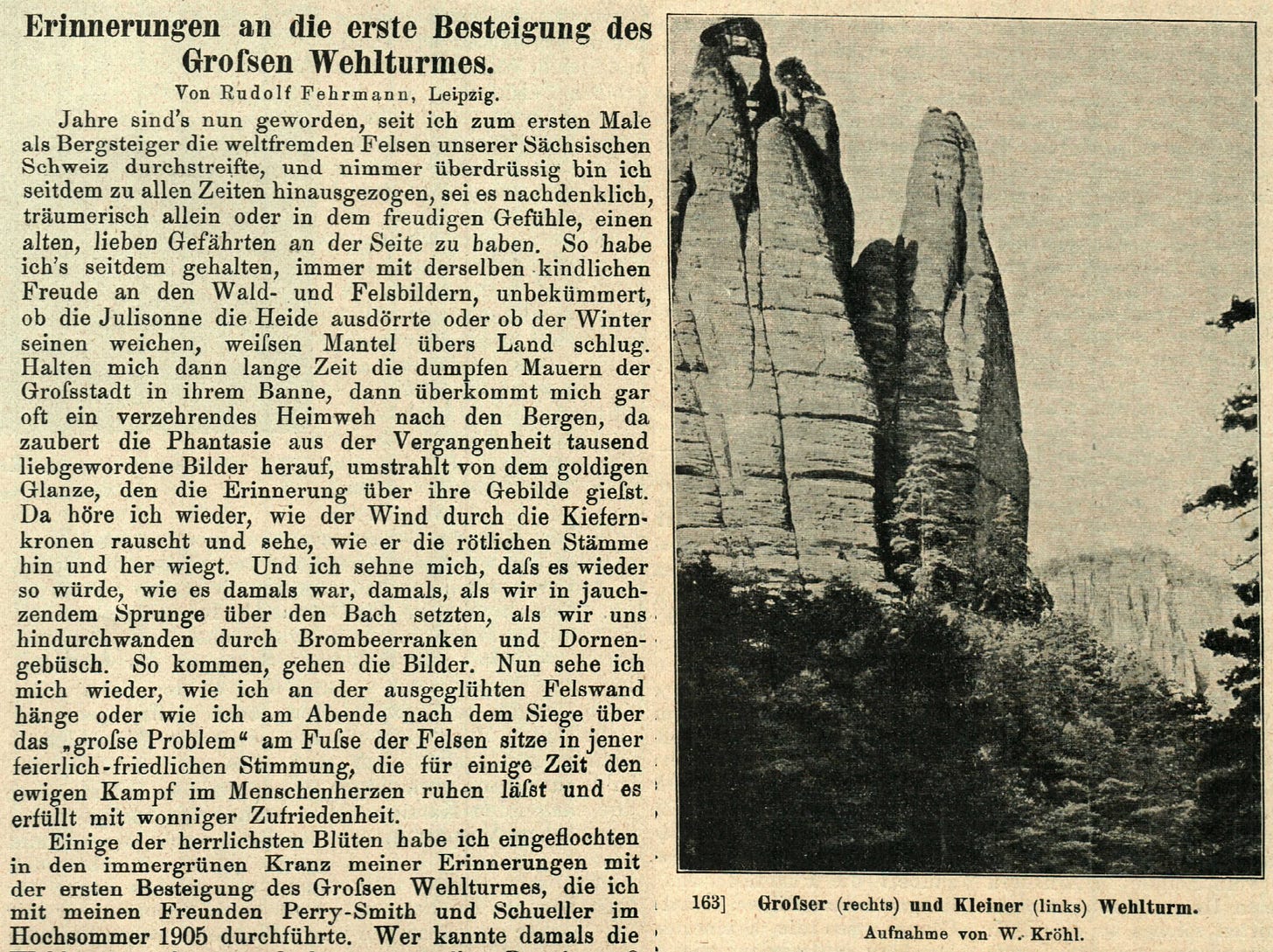

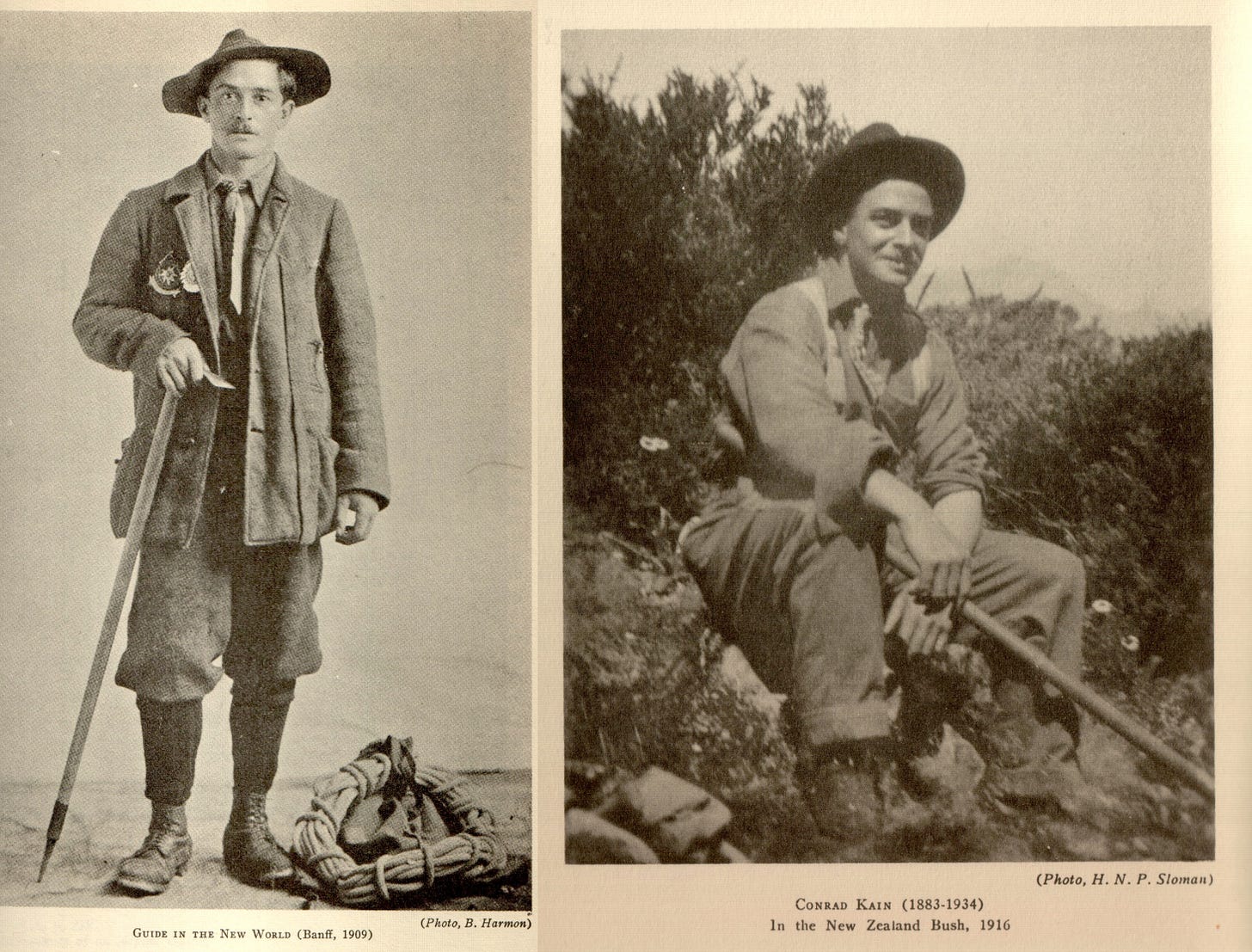

Oliver Perry-Smith

One of the first Americans to fully embrace rock anchoring climbing technology— pitons and bolts—to advance climbing standards, was Oliver Perry-Smith, born in 1884. Born to a wealthy family in Philadelphia, Perry-Smith’s father, a renowned chess champion and poet, was killed in 1899 in Cuba as a captain in the Spanish American War; his mother soon remarried and moved with her new partner to Dresden. Perry-Smith had shown adventurous spirit scrambling up and down cliffs near Bar Harbor, Maine (now Arcadia National Park) where he spent summers growing up but discovered a whole new world of climbing when he moved to Dresden in 1902 as an 18-year old youth, acquiring an early-model Bugatti sports cars and climbing throughout Europe. From 1903-1914, he climbed some of the hardest rock climbs in the world in the Elbsandsteingebirge near Dresden, then known as Saxon Switzerland, initially as training routes for the western Alps and then as an end to themselves. Rudolph Fehrmann, a local leading practitioner of visionary direct lines, mentored Perry-Smith, and their partnership found many great adventures involving bold free climbing and solos, but also placing protection on lead.

J, Thornington reports: “Perry-Smith was eager to ascend the Torwächter, and, when it seemed that a competitor might snatch this prize, began to curse and wanted to leave at once. But first they had the blacksmith make safety and rope-off rings. Arriving at the overhang, Perry-Smith drove in the safety ring and roped to his companions. The final wall was covered by thin lichen, still wet from rain, but soon they were on the summit, listening to cheers from friends on a nearby tower.” (AAJ, 1964). These sandstone bolts are described as 10mm in diameter, 150mm long, and placed in 14mm holes “with wood or lead pieces to make it fit solidly.” These rings took up to two hours to install, sometimes in precarious and exposed positions.

Perry-Smith also climbed many of the newer routes on the steep rock of the Eastern Alps, including new routes on the south wall of Campanile Basso and Vajolet Towers in 1908, where lightweight steel anchors were becoming more widely used, referencing the use of pitons (and sometimes the lack of) on these ascents. He also climbed many of the difficult alpine routes in the Western Alps, including the first ascent of the northeast wall of the Weißhorn with G. Winthrop Young and Joseph Knubel (guide), and a solo traverse of the Matterhorn on his third time up the famous Swiss peak.

Few English periodicals reported on Oliver Perry Smith’s feats at the time despite a prolific decade, including at least 35 first ascents (a near-complete list of his sandstone climbs here). Hard and bold free climbing was rarely reported in international mountaineering journals at the time, and even in Europe, the first article on the Saxon rock climbing only appears in the 1908 DuÖAV, the same year Fehrmann produced one of the first guidebooks to the area. The only climb of Perry-Smith’s outside of the Dresden area noted for many years was the first ascent of Cima Piccola/Kleine Zinne in the Sexterner Dolomites, which Fehrmann had mostly led, despite the fact that routes such as Perry-Smith’s first lead of the south wall of Campanile Basso in 1908 were on par with the hardest free climbs of the era. Perry-Smith also became a champion skier during his time in Europe and was a member of several alpine and ski clubs. In 1911 he married Agnes Adolph, the daughter of a well-known sportsman and hotel owner, and had their first son, Oliver III. In 1914, prior to the outbreak of WWI, he returned with his family to America and settled into a new life.

It does not appear that Perry-Smith did much climbing once he returned to the USA, though later he became friends with Fritz Weissner after his immigration to USA; Perry-Smith’s son reported his father had climbed a route on Wall Face in the Adirondacks with Weissner many years later. Indeed, it took many decades before the American climbing community learned of the bold climbing and the expert use of new tools and techniques that Oliver Perry-Smith had achieved during his time in Europe.

“Swiss Guides” come to North America.

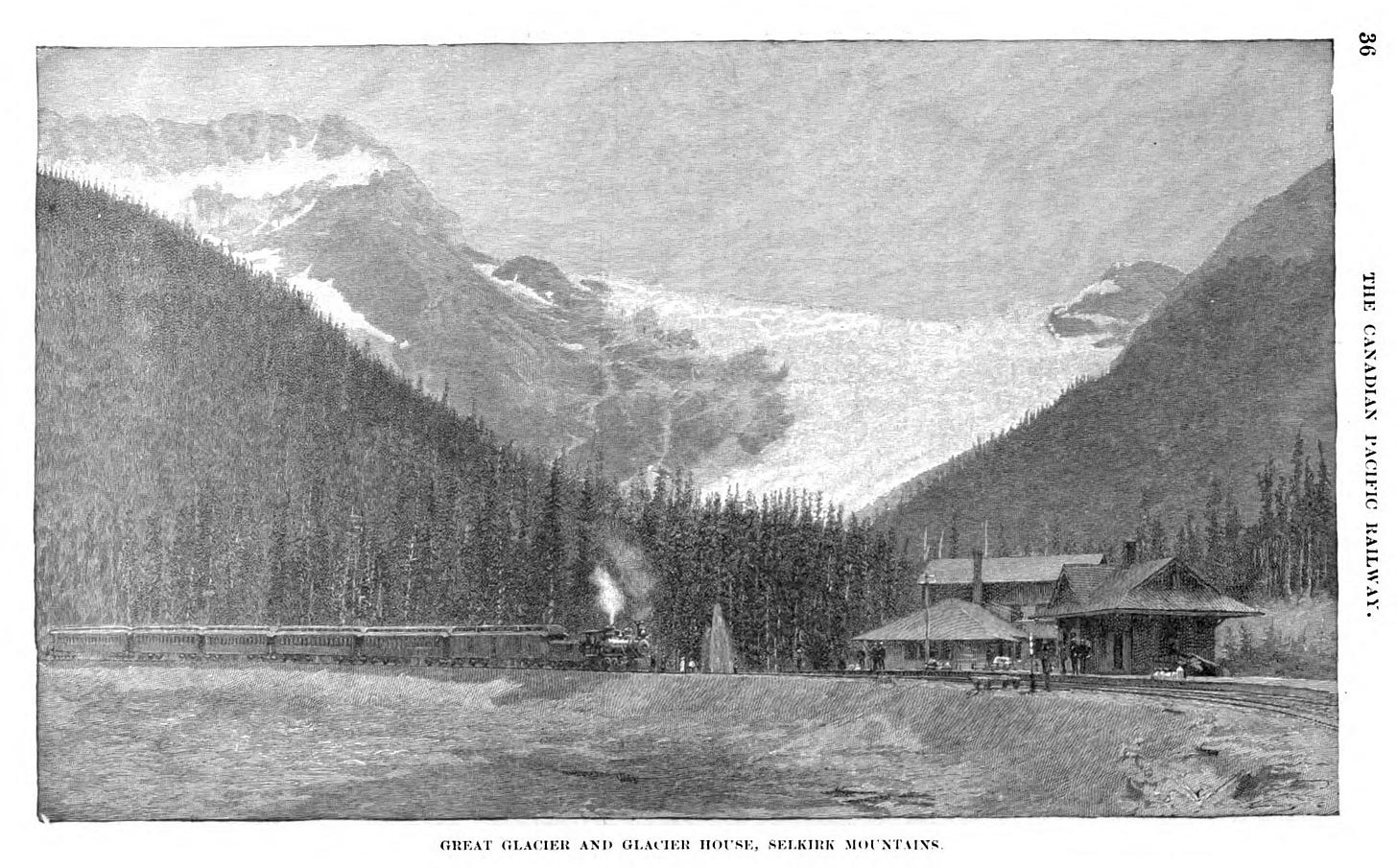

Interest in steep rock walls that required improved rock anchoring technology to developed slowly in the Americas. The major clubs were largely focused on the biggest peaks, and technical rock climbs were still only considered an exercise. Indeed, some of the best overall guides to North American climbing in this era were published in the German-Austrian Alpine Journals by travelers and mountaineers who were more familiar with the limits of the possible on steep rock. DuÖAV articles in 1900 by Jean Habel (“In the North American Alps”), and a 1910 article by Robert Liefmann (“In the Mountains of the United States of America”) provided fine fodder for German language speakers, including details on transportation and lodging around the country. Liefmann spent eight months on a “study-tour” comprehensively describing the United States and Canadian climbing developments, noting which major peaks had been climbed, and those still unclimbed. And indeed, many of the first technical climbers to come to North America were German-language immigrants from Switzerland, Austria, Italy, and Germany, sometimes escaping war, rising fascism, and economic depression. And, as in the case of the Canadian Pacific Railway promoting alpine resorts along the railroad, firms hired European guides as early as 1897 to offer guiding services in the North American mountains (as well as invited guest speakers such as Whymper). The guides were often known locally as “Swiss Guides”, even though they were not always from Switzerland. It was primarily those who had climbed technical routes in the Eastern Alps who brought new techniques to America, in the period starting in 1916 and into the 1930s, many of the next steps in technical rock climbs in North America were evolved by native German readers (as most of the literature on the new tools and techniques was either in German or Italian), including Conrad Kain, Joe and Paul Stettner, Fritz Weissner among others. But this is not to say there were no intrepid Americans and Canadians who also traveled to Europe, learned of the new tools and techniques, established new standards on the North American rock, and eventually pushed the sport even further than what had been achieved in Europe; their stories will be covered next.

—-End early USA/Canada (to 1910)—

This article covered the background and context of a boom of big wall climbing that would take place in the 1930s in North America, and the next chapter will cover what followed once the new technology was embraced, and leading up to global big wall breakthroughs and innovations in the 1930s.

Conrad Kain (brief)

In 1916 Conrad Kain, the renown Austrian guide working in Canada and New Zealand climbed the most technical routes of the day in the Purcell range, including Bugaboo Spire (5.6), which he considered harder than his difficult alpine route on Mt Robson, which today is considered a much more serious proposition due to the length and objective hazards.

Albert Ellingwood (brief)

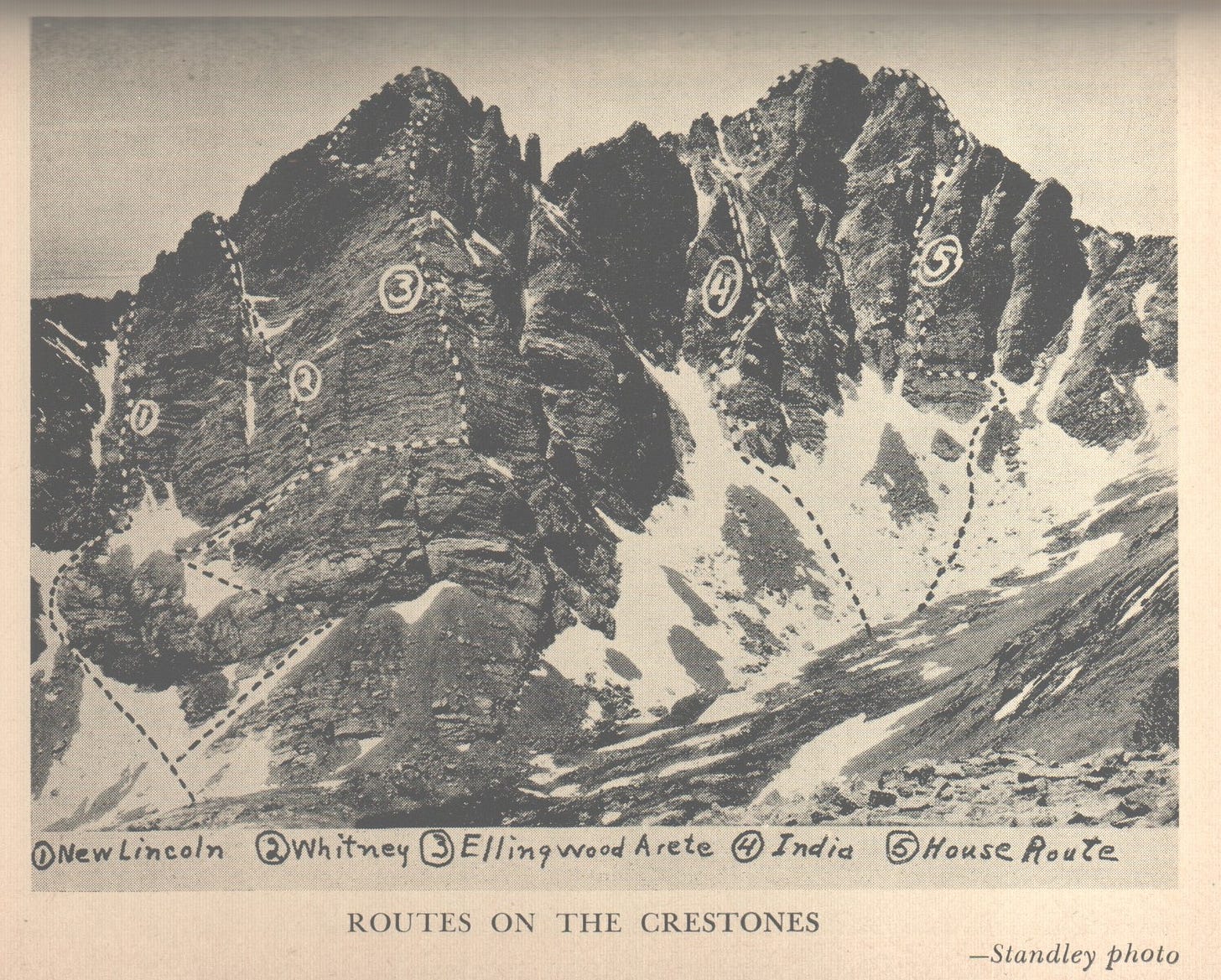

Albert Ellingwood, a Colorado College political science professor learned climbing techniques from visits to Europe pioneered artificial rock anchoring in Colorado when he climbed the Lizard Head in 1920 using three iron spikes similar to telephone pole steps. Today it is a loose and scary 5.7+ route and still the most difficult Colorado summit to attain. Ellingwood became the finest rock climber in the land, and his improbable 1925 route on the 2000 foot northeast buttress of Crestone Needle (5.7) with Eleanor Davis, Stephen Hart, and Marion Warner using only a rope and a braced belayer for safety was the most inspiring and the highest (14,197 feet) rock climb in America at the time.

Appendix/notes:

Mechanical Advantages in Climbing

When people think “Mechanical”, what often comes to mind first is machined metal, gears and hammers, grinding and pounding to achieve an objective. But soft, tensile-only components are also mechanical parts of rope and anchor systems, as any engineer doing the calculations recognises. The improvements of rope-piton-link systems in the mid-20th century cannot be underestimated in what new risks climbers were willing to take on the vertical.

In the first half of the 20th century, knowledge of new European climbing techniques spread around the world, filtering into the North American big wall landscapes—the Bugaboos, Rockies, Tetons, Wind Rivers, Adirondacks, and the Sierras. Pure aid techniques, pioneered in the Dolomites, were ever-refined starting with the first big wall ascents in Yosemite in the 1930s; simultaneously, North American climbers tested the limits of free-climbing and falling with piton and rope protection systems.

For an excellent overview of early mountain climbing in North America, see Ways to the Sky, A Historical Guide to North American Mountaineering, by Andy Selters. Ways to the Sky, 2004.

For Canada history, Chic Scott’s Pushing the Limits (2000) is unmatched.

Roof of the Rockies, W. Bueler (2000) also very good.

Yankee Rock & Ice, Laura and Guy Waterman (1993) amazing too.

More research by John Middendorf: HTTP://www.bigwallgear.com