Ice Tool Developments and Innovations (brief)

sidebar for Tools for the Wild Vertical draft by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Ice Tools Developments

General Evolution—ice tools overview to late 1970s.

Most of the research in these pages are about the tools for bigwall rock climbs, but let’s examine some of the evolution of the most iconic piece of mountaineering gear, the ice axe, since the beginning.

Early History: The first axes were cast:

1800’s: In the 1800s, the metal (steel) components were hand-forged in shops like this:

Later 1800s to 1950s: Designs evolved with added adzes, first vertical like a wood axe, then horizontal, which was an improved design for cutting steps in glacial ice. Whymper was an early proponent of the horizontal adze, but in his famous portrait, he has an axe with a vertical adze.

The shafts on early ice axes were generally over a meter long, doubling as a comfortable walking stick. As climbing became more popular and demand increased, ice axes were mass-produced with drop forge machines. The design remained pretty much the same for over 100 years with only a slight droop on the pick.

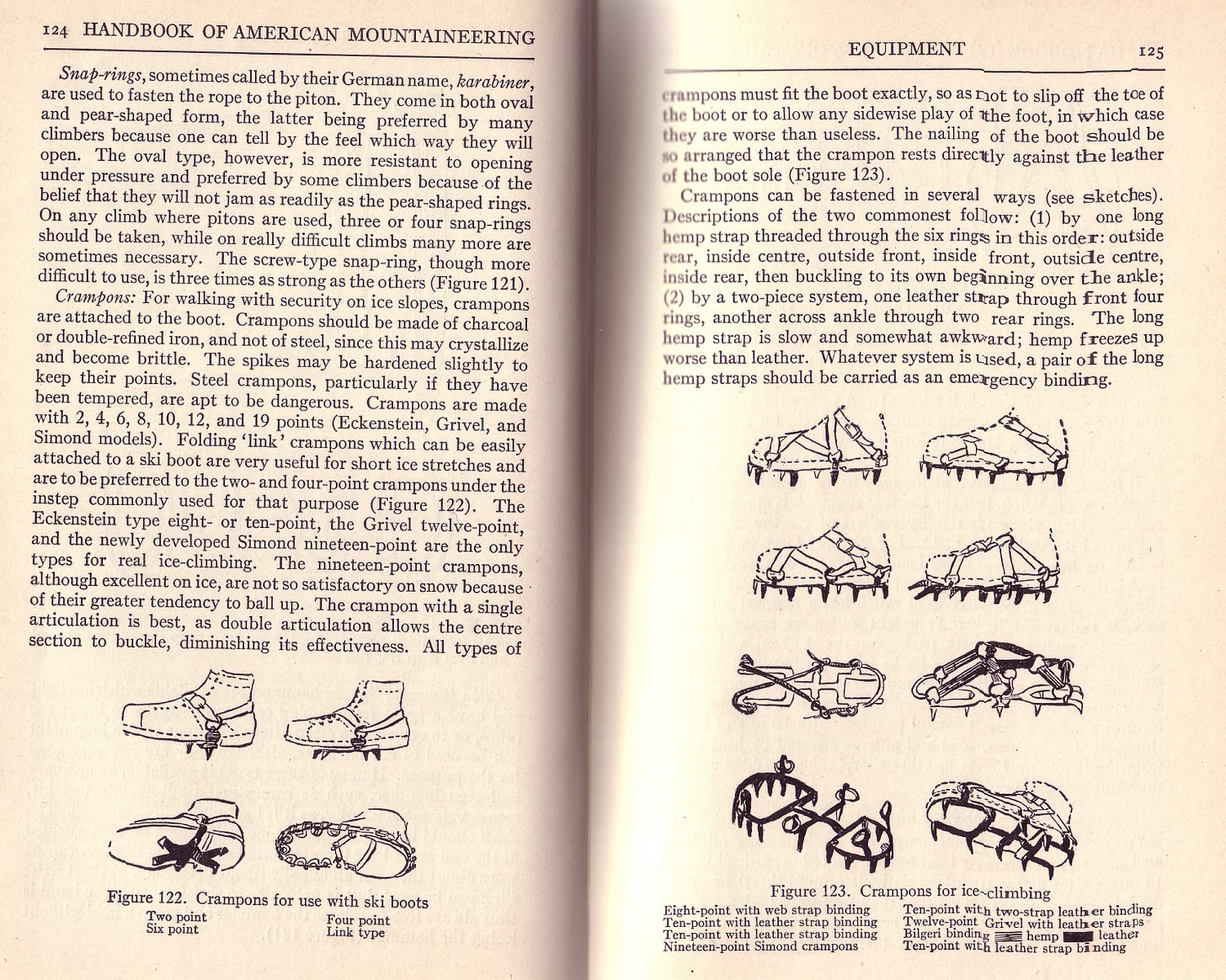

For climbers who were mostly using ice axes to get to get to a rock climb, Kenneth Henderson in the 1942 Handbook of American Mountaineering recommended cutting stock shafts to as short as 15 inches long (38cm) so the tool could be carried in a pack without interfering with climbing.

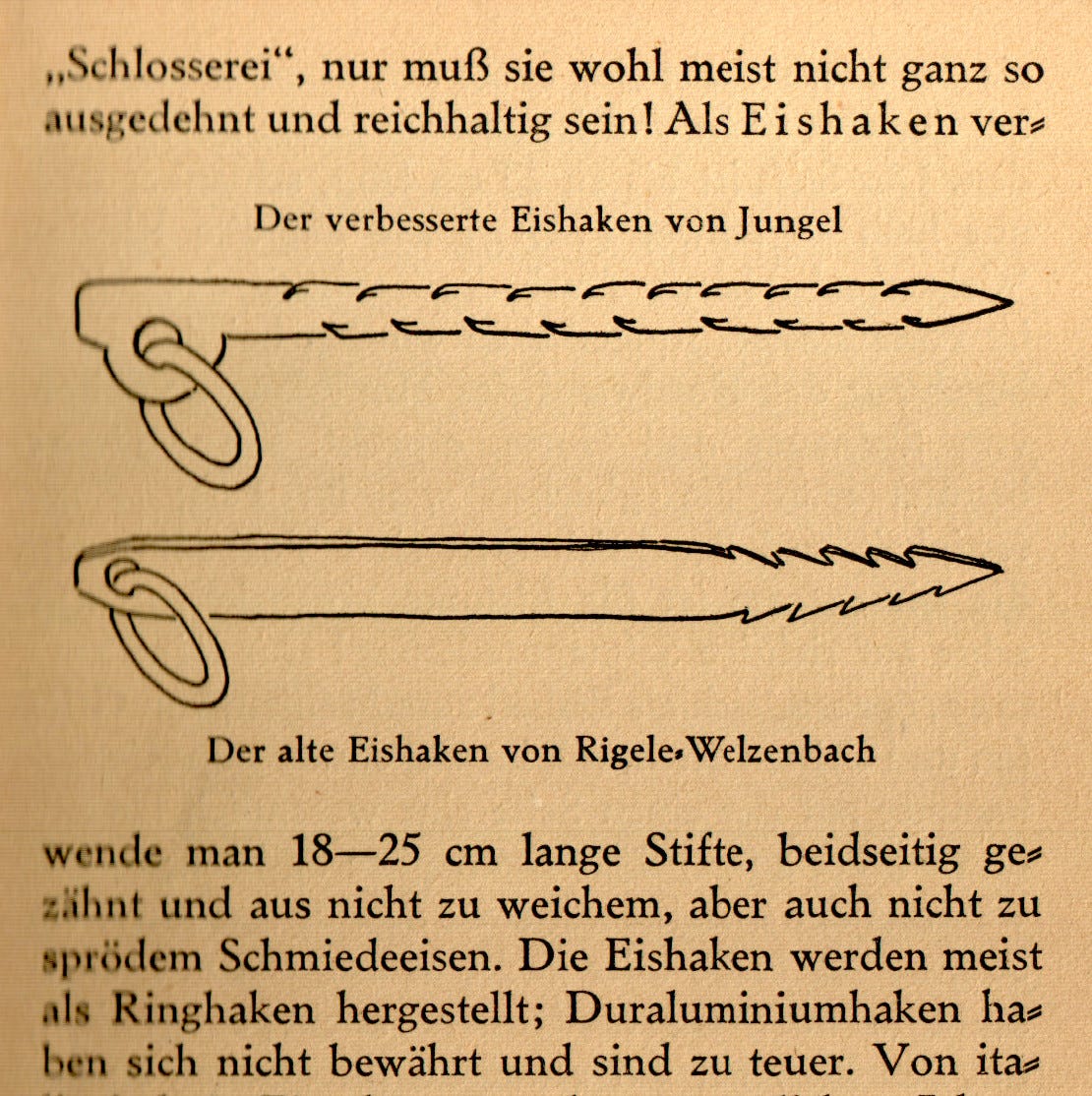

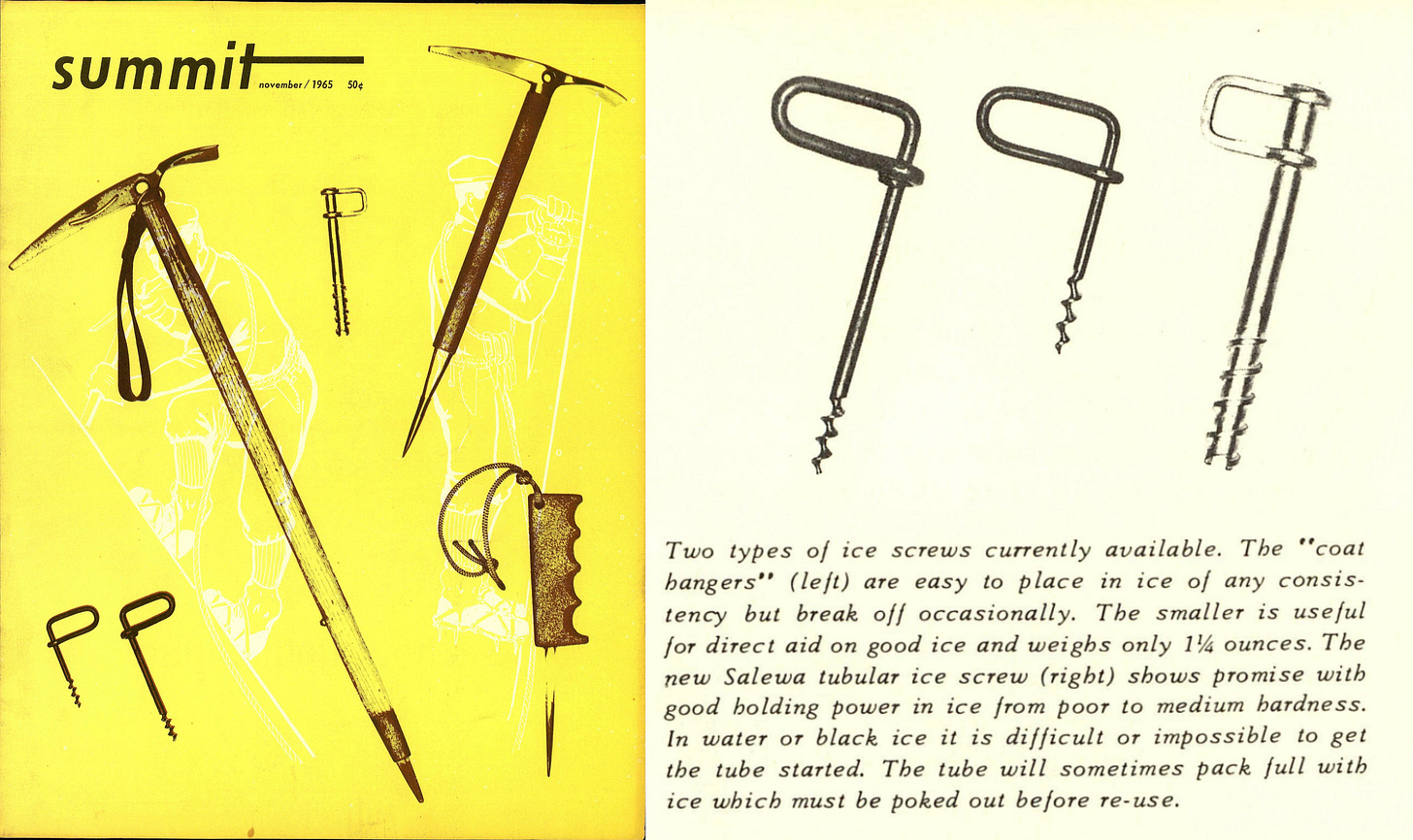

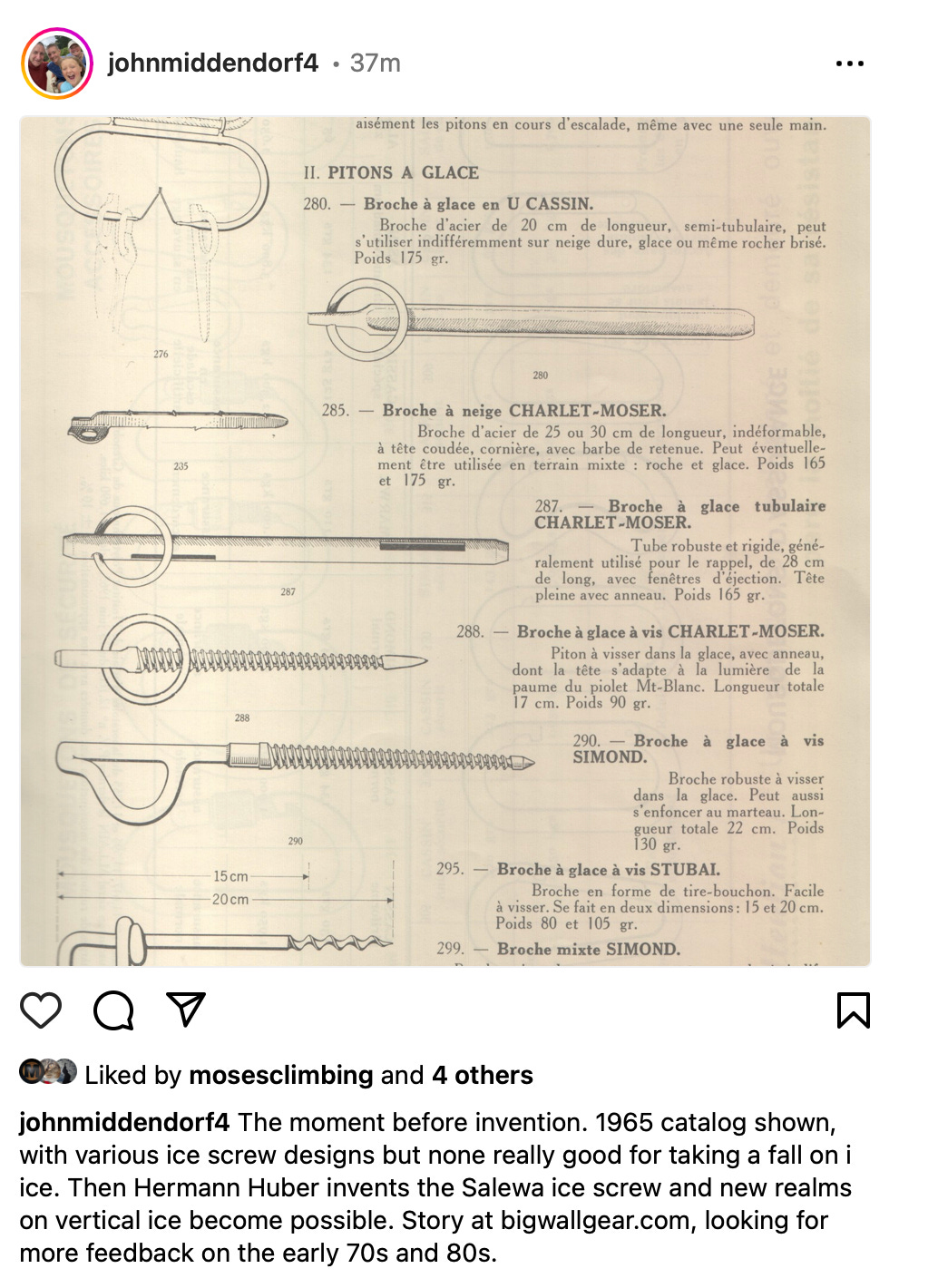

Ice protection 1930s

Ice pitons in the 1930s were simple shafts of flat steel. Various serrated designs were developed, in order to conceptionally (not always practically) increase pull-out strength— a simple design that remained the standard until the late 1950s. This type of ice piton could support the weight of a climber but would pull out in a long fall.

Ice pitons were installed easily into glacial ice with a hammer:

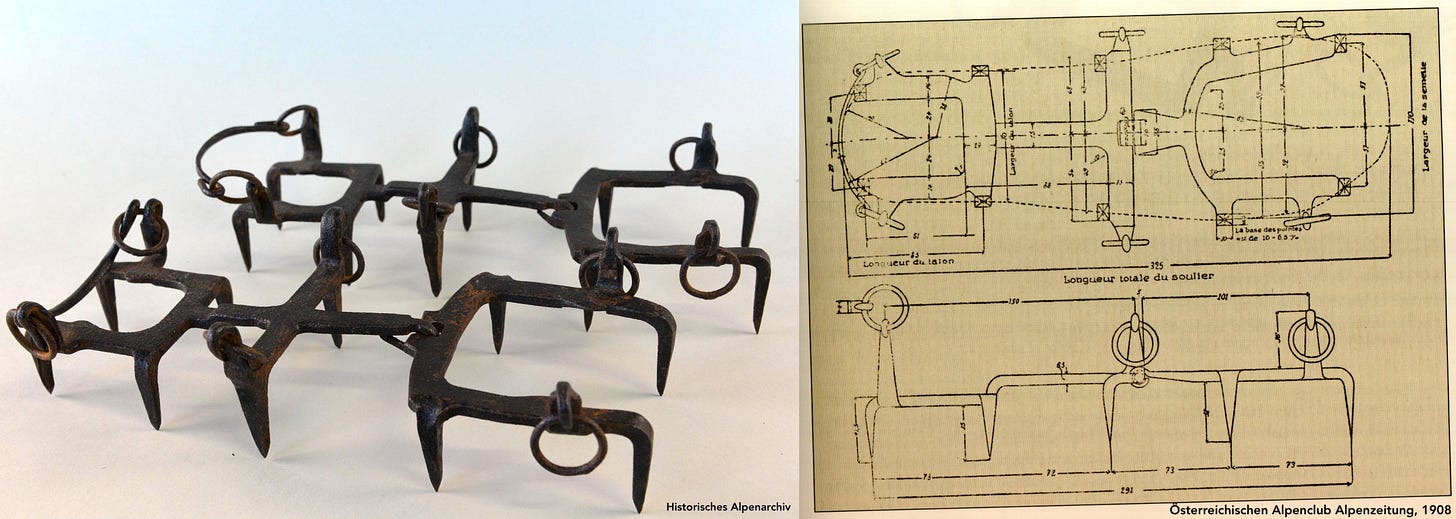

Crampons 1910-1950s

10-point crampon TECHNIQUE 1930s

Front Points Appear

Various other experiments

Jump to the 1960s and the transition to two tools for steep ice.

Front point design refined

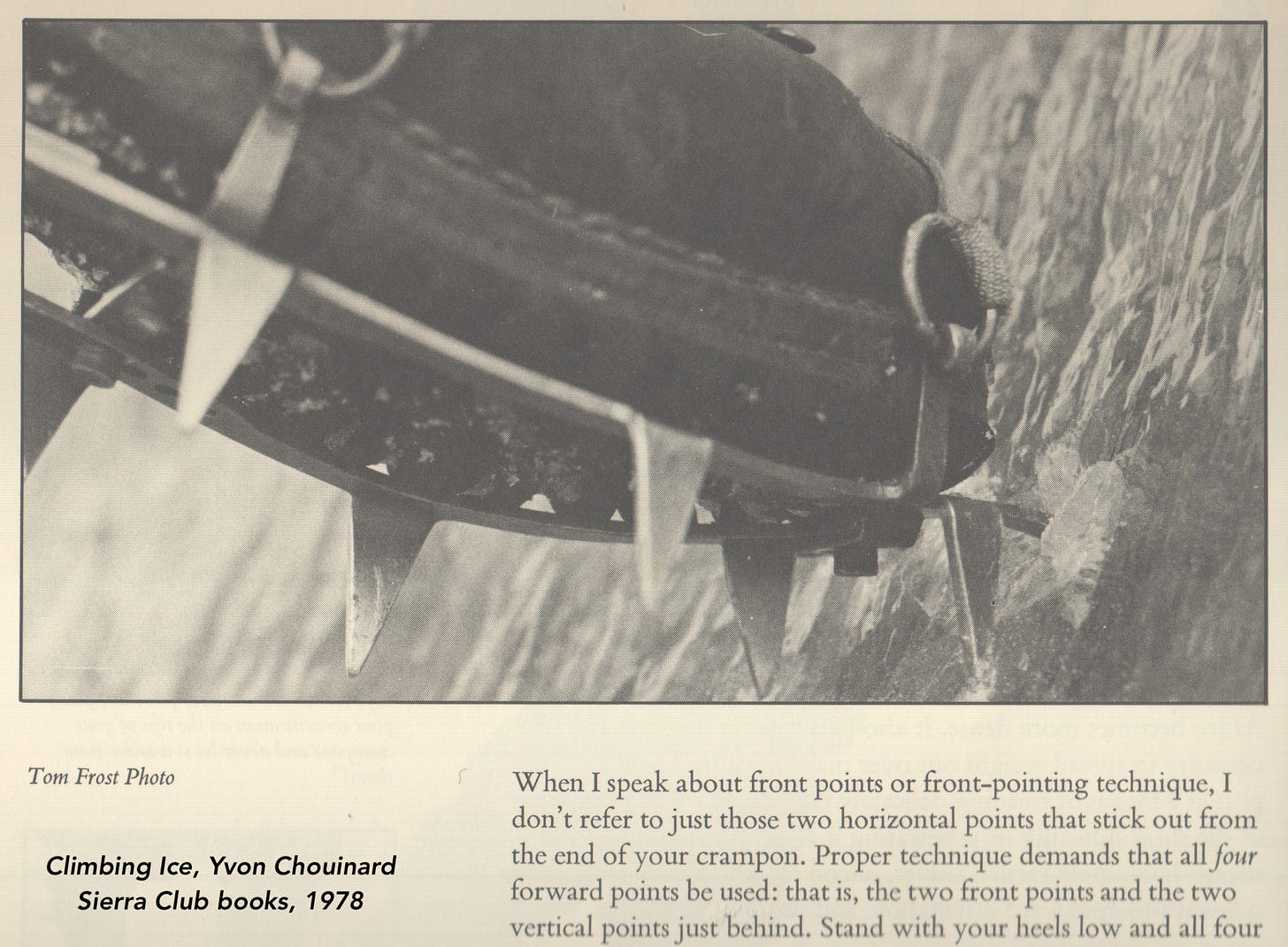

Even though front-point crampons had been manufactured by Grivel since 1927, for decades most climbers continued with the versatile hinged 10-point Eckenstein-type crampons for most climbs, resorting to the age-old technique of chopping steps on the steepest ice, until the advent of fully rigid front-point crampons, as hinged crampons are tenuous when front pointing with flexible boots due to flex of the boot/crampon system. Strength and durability were also issues with early designs, as thin sharp front points needed to penetrate hard ice were prone to failure (and were not designed for modern higher-stress dry-tooling on rock techniques). Front-point crampons were originally called “toe point” crampons in the USA, and in the era prior to fully rigid plastic boots, the rigid crampon design was essential for the steepest waterfall ice.

Footnote: During his first trip to the Himalayas during the 1963 Himalayan Schoolhouse Expedition led by Edmund Hillary, Tom Frost once explained to me how he zenned in on watching the pattern of his partner’s spikes on various angles of the glacial ice, and an improved rigid crampon design that would work with flexible boots came to him in a flash. The adjustable rigid frame design closely follows the edge of the boot’s sole, eliminating flex between the boot and crampon. His engineered design using six parts fastened with set screws, adjustable for any size boot, became standard on many of the hardest climbs of the 1970s and 1980s.

Into the 70s and 80s

In 1971, Jim McCarthy published “Coming of Age—Ice Climbing Developments in North America” in the American Alpine Journal, foreseeing the incredible advancements in technical ice climbing that was to come in the following decade. And as the standards rose and new techniques developed, so did the variety of specialized tools for the job, and he considers the rise of variants, such as the improvements in secure tubular ice pitons and more radical droops of ice axe picks. McCarthy concludes, “Armed with these tools and techniques a small but rapidly growing number of American ice climbers are busily engaged in a great game called “Find the Ice.” In the last two years truly challenging climbs have been discovered in the Pacific Palisades, the Northeast and the Canadian Rockies. The adventure begins.”

The Droop transforms into a Beak

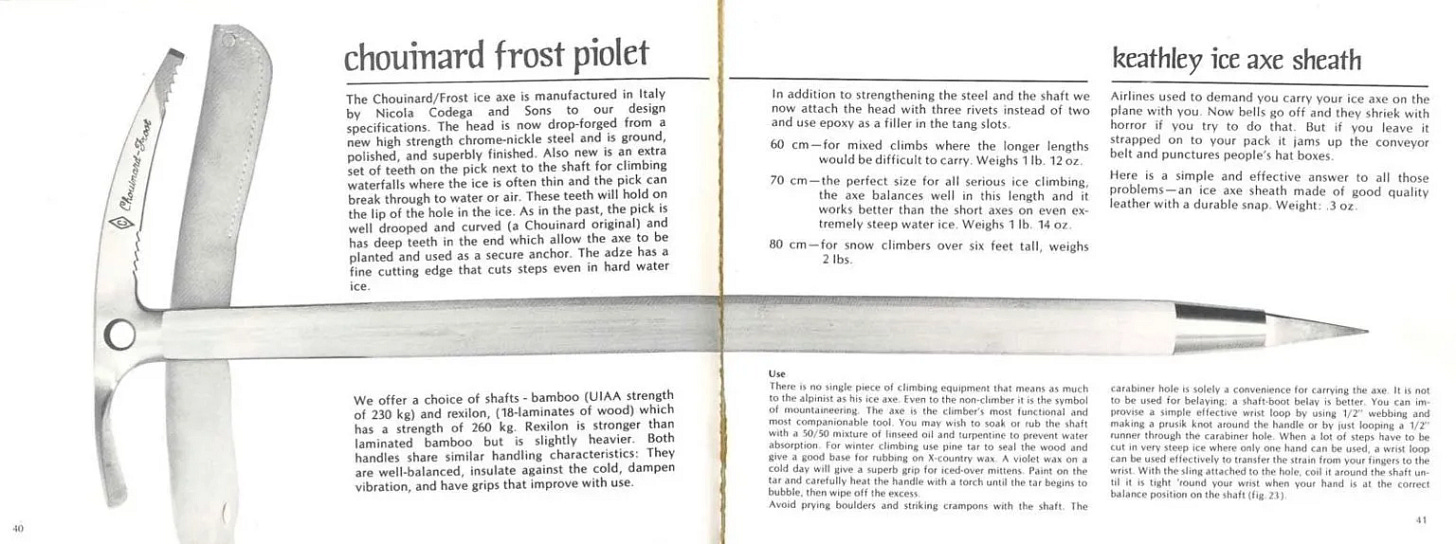

In the late 1960s, the Chouinard/Frost Piolet added a bit more droop to the traditional pick, which held better in thin ice (than a straight pick) and was easier to swing into the ice. In the early 1970s, the Snowdon Mouldings Curver took the concept a step further with a curvature that followed the radius swing of the short-shafted tool.

One of the more significant early developments in the late 1960s, which took time and refinement before it became a standard design, was the Terrordactyl by Hamish MacInnes, with a radically angled straight pick. The Terrordactyl required a different placement technique in ice than tools with curved picks, which were designed to swing through an arc. The MacInnes’ design required more of a hooking motion to set the tool, and would hold well in even the thinnest ice (and on rock). Both types of pick designs were in play for a while, but as steep waterfall ice became popular, the hook-type front picks in various forms, angles, etc, became the prevalent design starting with an era of innovation in the 1970s and still today.

This has only been a brief overview of ice climbing tool development in the early period; for more detail on the ice tool development, the book Alpinisme, La Saga des Inventions (Gilles Modica, 2013) has details. For the best online museums for the older tools, see Marty Karabin’s amazing collection and Vertical Archeology.

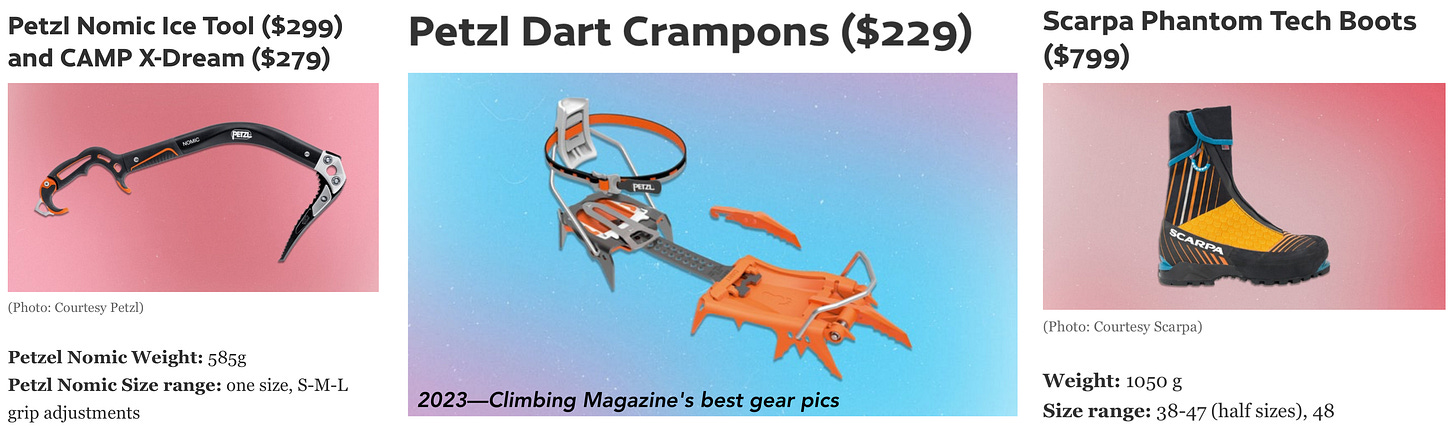

Conclusion: The pace of innovation

The evolution of mountaineering's iconic tool, the ice axe, alongside other spawned tools of ascent such as ice screws and crampons, illustrates a common pattern in innovation: a tool undergoes initial development and refinement, with a number of variants favored or dismissed by proponents. Once a tool reaches the stage of significant production, its design might remain fixed for periods, sometimes decades, such as the design of the long ice axe with slightly curved pick and horizontal adze. Sometimes a new idea is presented but not immediately adopted widely, such as when the Terrordactyl with its modern steep hooking pick appears, the prior (curved arc) style continues to be refined concurrently for a time. Some designs, like front point crampons, are introduced but remain less popular; then, often with the emergence of new materials and refined designs, in this case almost 40 years later, a new iteration of the design appears and captures the entire market. Often it is the small producers who are tinkering with batches of new variant designs, and old ideas are sometimes merged: ice screws evolved from hammer-in, to screw-in, then back to hammer-in (and screw-out). Engineers with an interest in climbing work behind the scenes, analyzing and testing new tools while providing fresh design directions. Over time, design variants tend to stabilize, and eventually, a specific and versatile tool design becomes mainstream.

Leo Maduschka identified a major shift in climbing sytles in the 1930s, when he wrote a treatise on how “modern icecraft follows modern rockcraft”—in contrast to an earlier age when snow and ice were the first steps in mountaineering. And as new techniques and skills are developed during these shifts, the climbers seeking new standards of difficulty are often the drivers for change. However, many new ideas remain purely conceptual until a collaboration among talented individuals—artists, engineers, product testers, and producers—comes together to transform the idea into a usable tool. This art of design is a much-studied field, and the evolution of ice tool design highlights the incremental and sometimes staccato development and refinement of new tools.

Footnote: there would be a bazillion examples of imagined ideas, ranging from grappling irons and suction cups to refinements of existing designs that have the potential to enhance the tools and techniques of climbing, yet fewer examples of one-off physical prototype designs that could be field tested. And much fewer yet of ideas that make it to a production phase—the fun of prototyping a small batch of a product quickly becomes work to create a production system and requires a very broad engineering mindset that becomes the Edison 99% perspiration.

Note: I have gotten great input on the transitional developments, such as how the ice dagger helped point the way (no pun here) for steeper picks, and how Hamish found inspiration from the design of ship anchors for his Terrordactyl—these will be added when I compile this material into Volume 2 of my ongoing research. And also how the first batches of the Chouinard Frost rigid crampons weren’t quite right with the heat treatment leading to failures when used with flexy boots—an important point regarding the pace of innovation. Thanks, Duncan, Kevin, Lindsay, and others!

Next: more on Bigwall Bivouacs, part 2

We’ll next consider how general bivouac equipment evolved, so we will have a look at what was available in the 1930s next.

I have a pair of Eckenstein’s styled crampons found on Mount Hood’s Eliot Glacier