Minamiura

and the great tale of the 1990 Trango Towers Japanese Expedition.

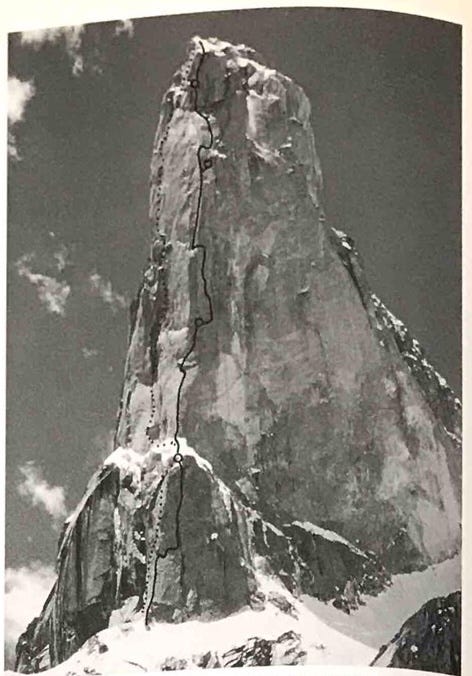

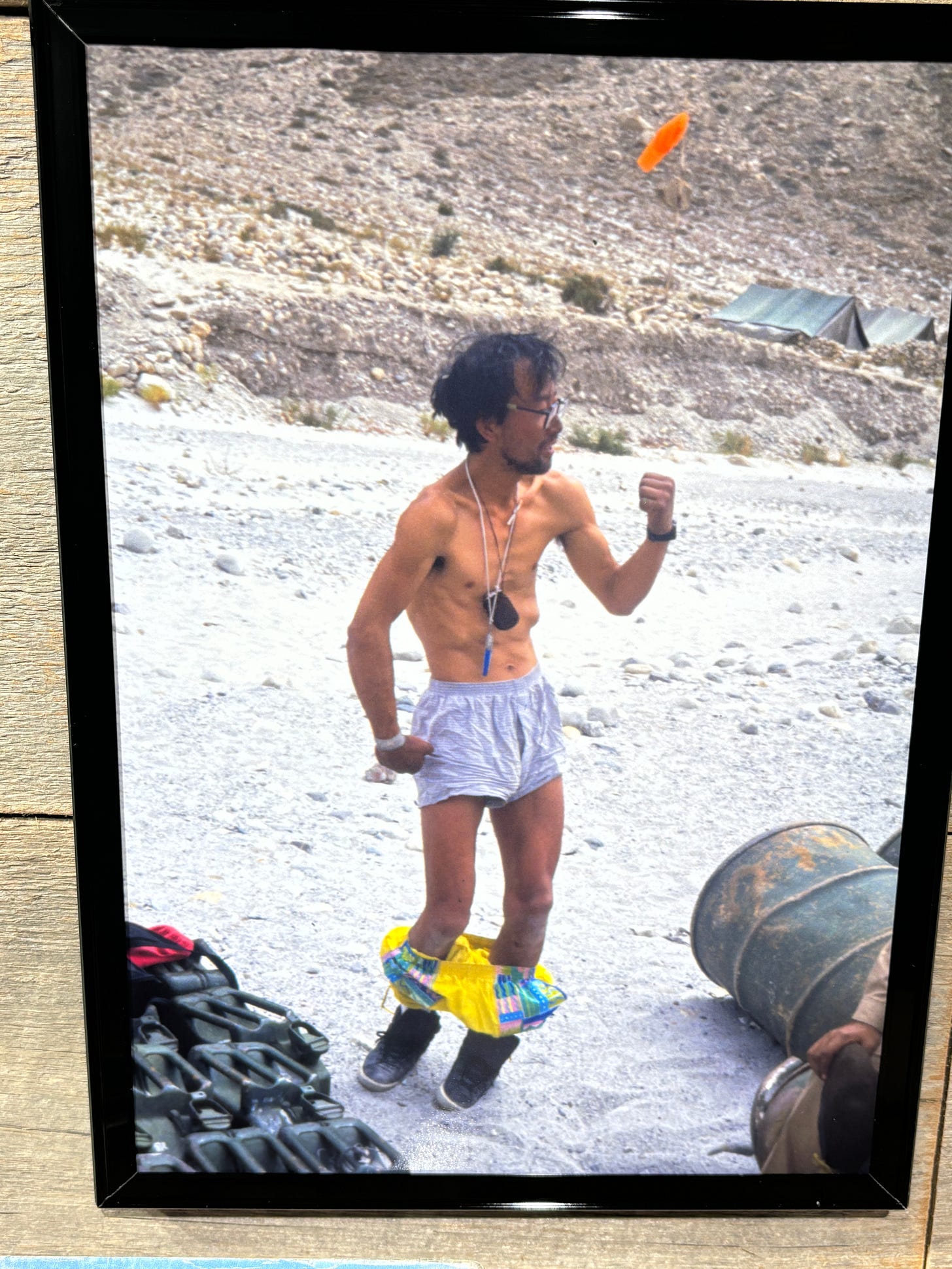

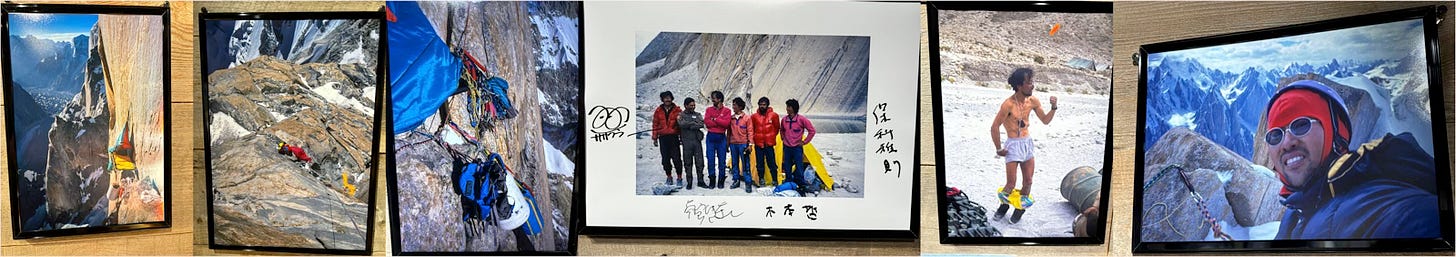

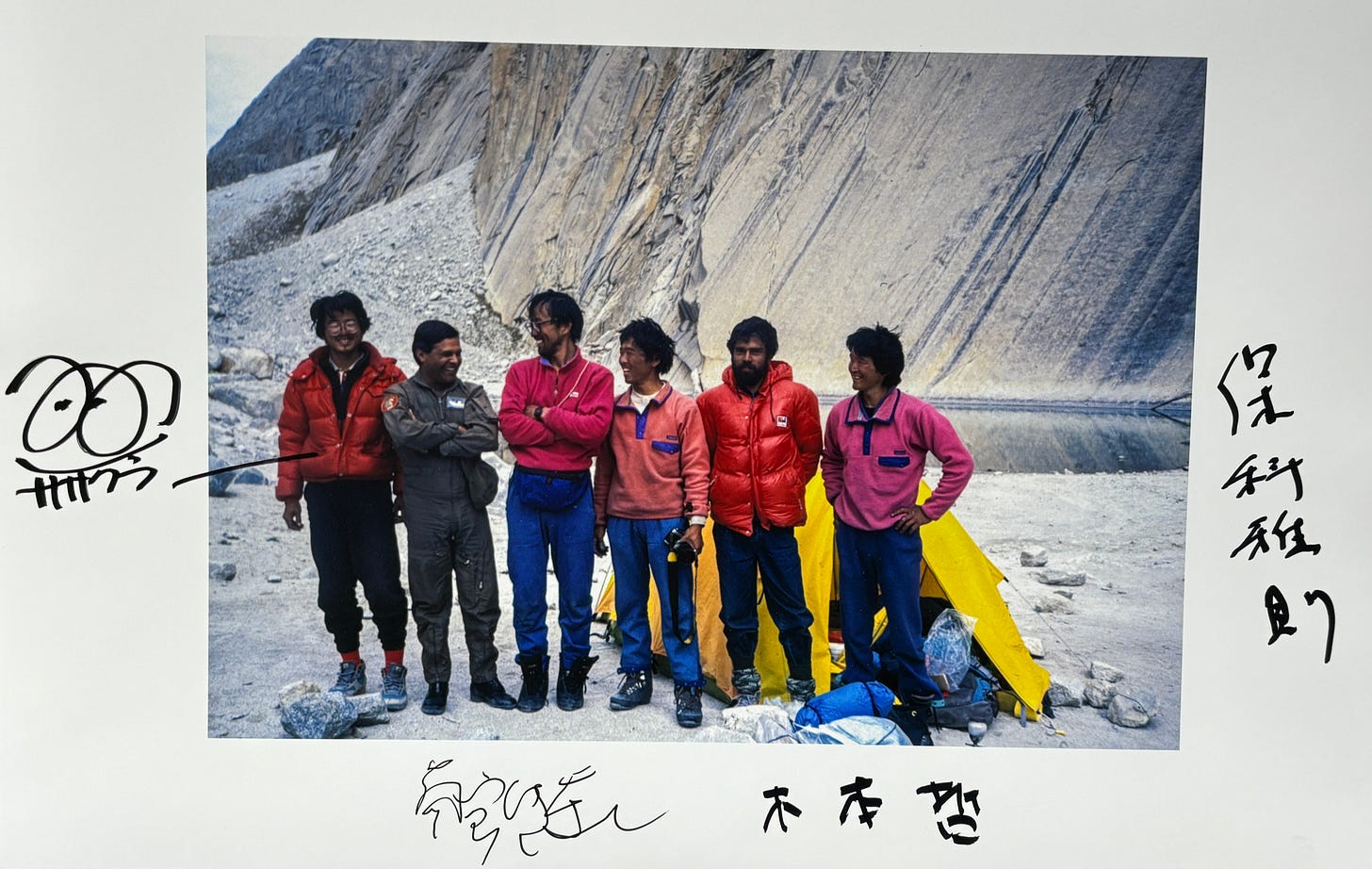

Recently I travelled to Tokyo, to meet fellow bigwall climbers from Japan. Naoe Sakashita has set up a very cozy mountaineering space in Ochanomizu called The Tribe, managed by Masanori Hoshina, with exhibit space and room for about 50 people for presentations. The exhibit I went to see and to present focused on the 1990 Japanese Trango Towers expedition, one of the most wild episodes in the history of mountaineering. I met and laughed with Takeyasu Minamiura, who had always been a mythical character since 1990 when out of-the-blue he soloed a new route on Trango Tower, an aesthetic and difficult line that many had eyed, with failed attempts by some of the best bigwall climbers in the world.

At the time, remote bigwall climbing was kicking into a new gear from the pioneering period of the 1980s, and huge breakthroughs in remote alpine style bigwalls were being accomplished with new lightweight kit and smaller teams, using tools and techniques developed and refined primarily in Yosemite over the previous several decades. Minamiura’s story has been published in several periodicals but sometimes lacking the minute but important detail for the full imagining by other bigwall climbers, who knew how desperate it can feel on a remote bigwall in the best of conditions. What was it really like, alone and trapped high up on the most remote massive rock spire in the world, and whose only certain means of descent was to jump off a less than vertical 4000’ cliff with a ragged reserve parachute? The first thing Minamiura told me about the experience is that it was a team event, as he survived the solo ascent only with the help of his expedition members, Masanori Hoshina and Satoshi Kimoto, who made a fast ascent of the original British route on Trango Tower, which hadn’t been climbed since 1976, sometimes dangerously depending on shredded and weathered 14-year-old fixed ropes in interest of speed.

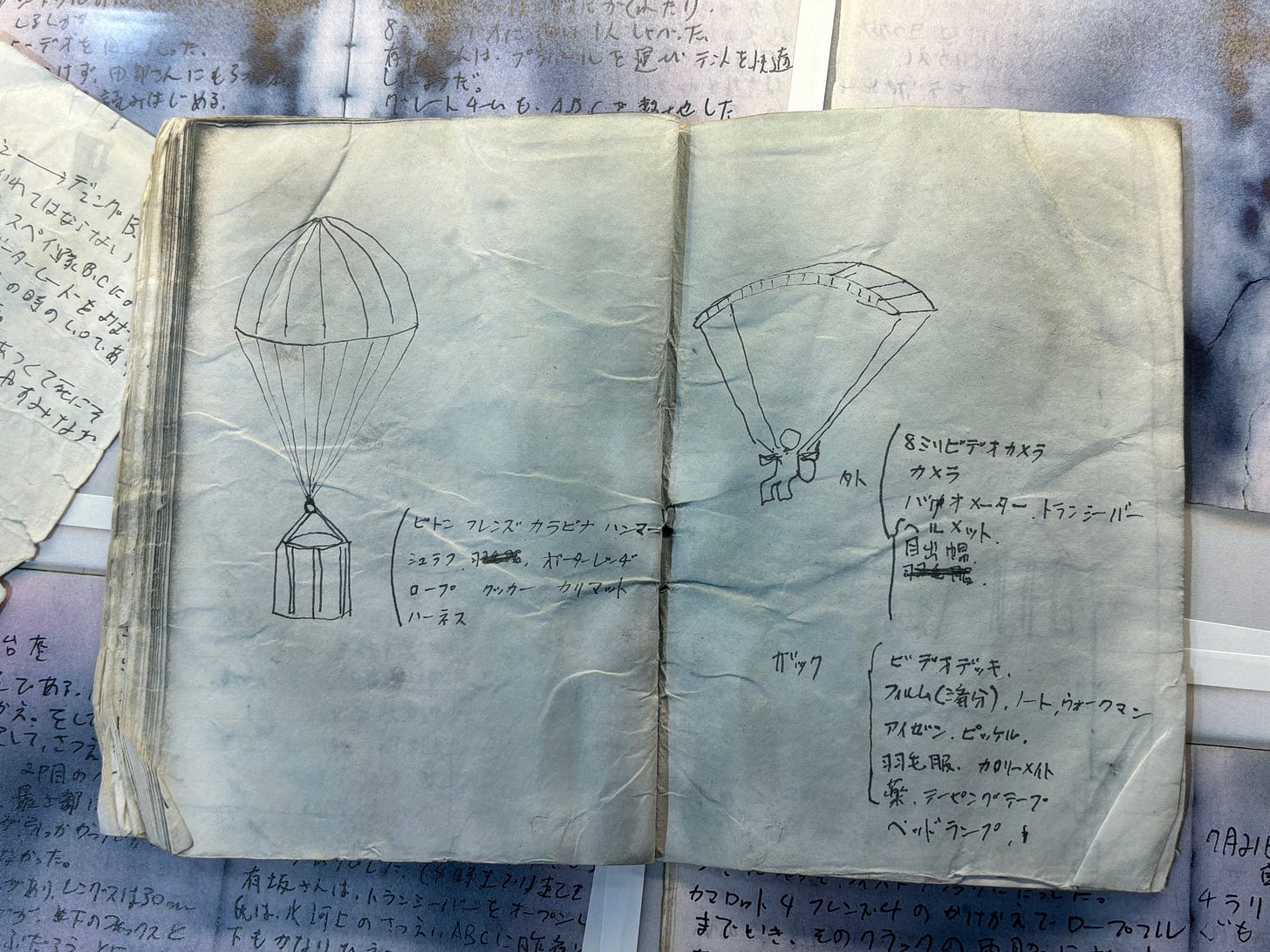

The sport of paragliding was developing at the time, and the initial idea was that a lightweight cliff-launch-able wing was destined to become the standard bigwall descent vehicle. Michel Fauquet had done just that, flying back to basecamp after completing a new route on the west buttress of Trango Tower in 1987, with an early paraglider design. In the mid 1980s, paragliders had a small number of cells (6-9), were shaped like a skydiving parachute, and had a very low glide ratio. In the late 1980s, paraglider design evolved for performance and speed, and the later generation wings were not suitable for low-wind-speed launches (until more recently).

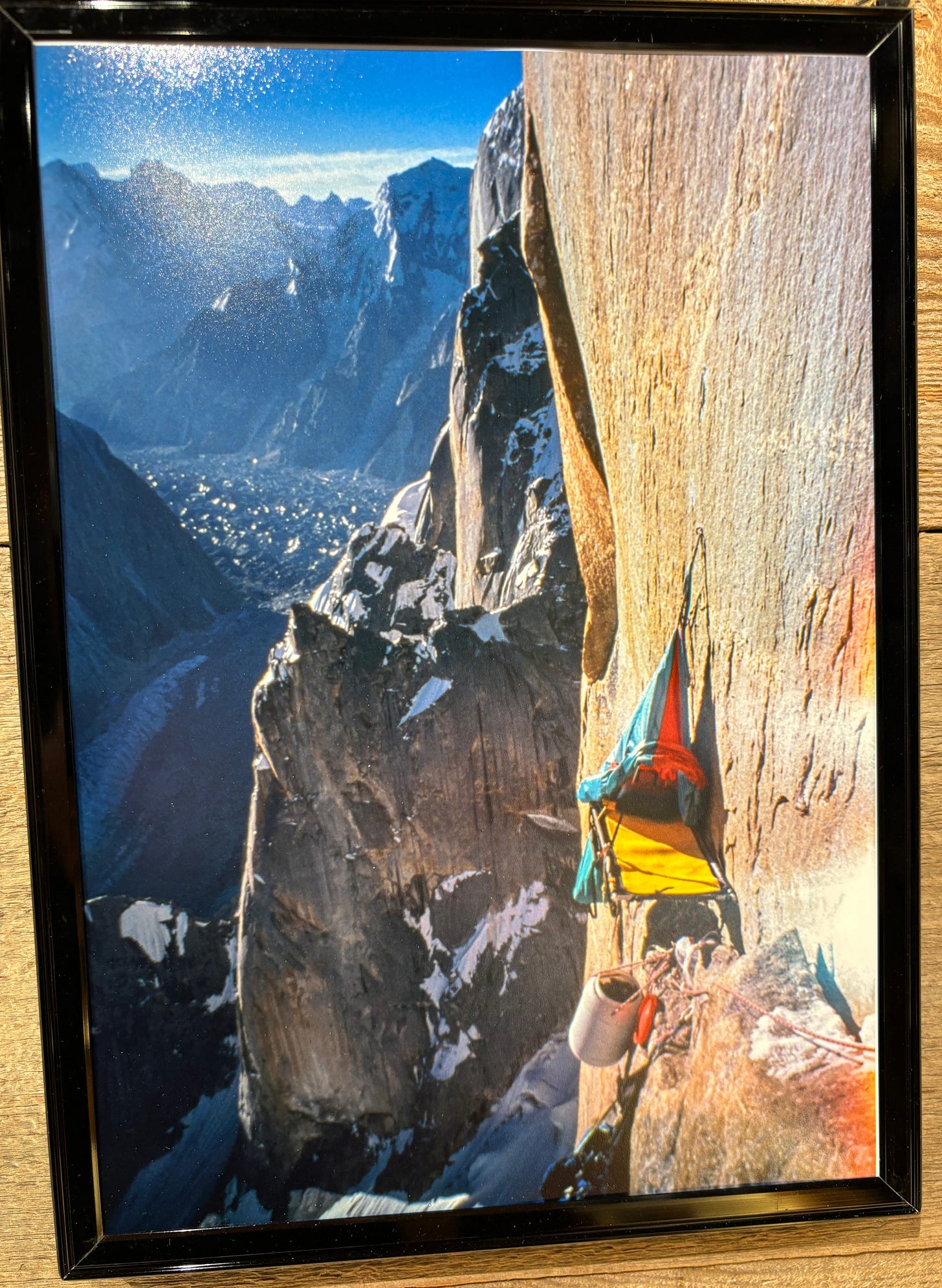

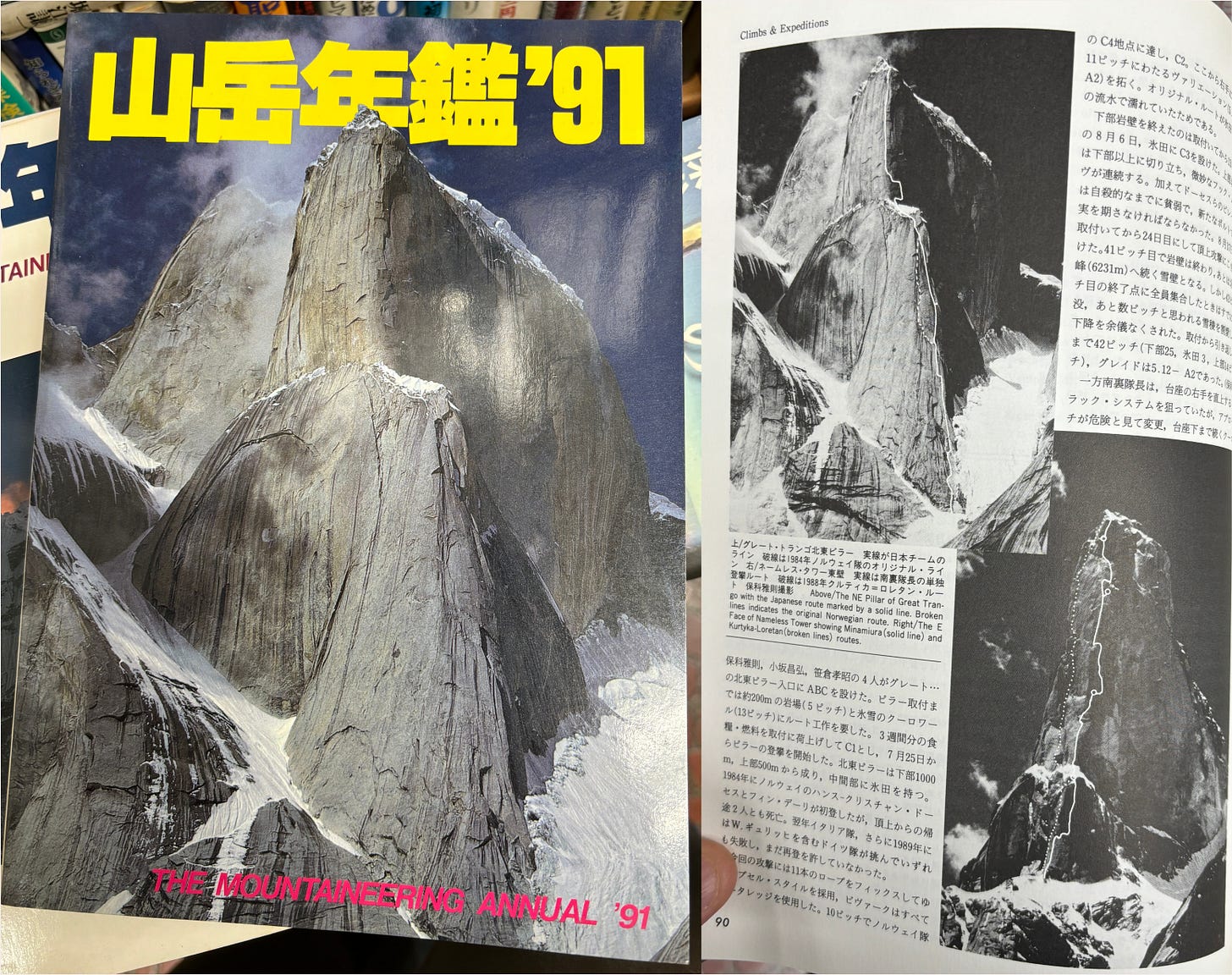

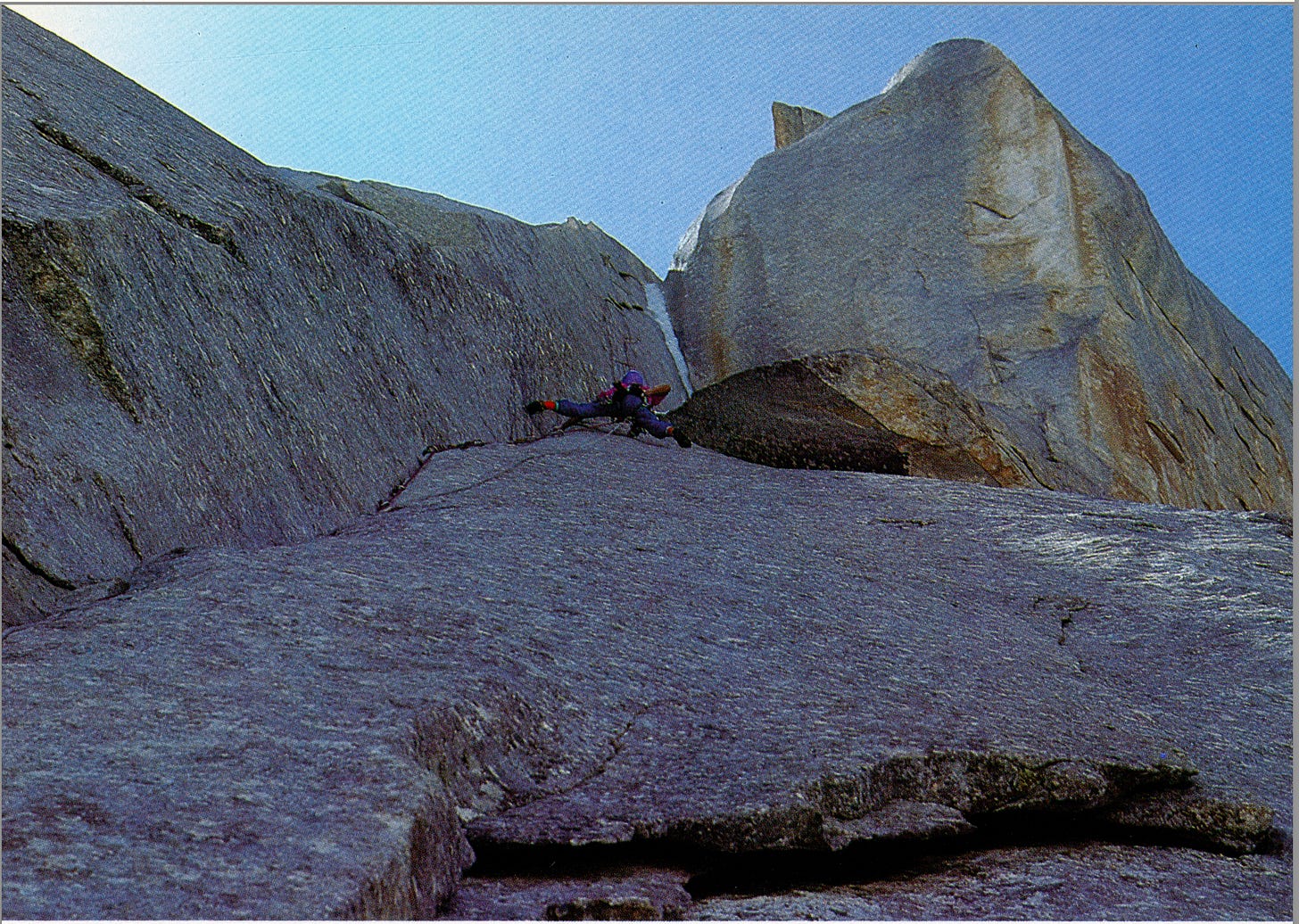

The 1990s were also a time of transition: two remote bigwall styles were in play. One was to bring thousands of metres of rope as was still being done on the highest mountains of the world, then installing the fixed rope bit-by-bit on the wall, gaining a few ropes of altitude at a time, and returning to lower camps to sleep on the more level terrain, eventually setting up for a final good-weather push to the summit after ascending fixed rope most of the way up. These ropes often get left behind once the summit is attained. The other style has become to be known “alpine bigwall style”, which involves using a minimum of rope, leaving no lifeline below, and spending multiple nights hanging on the wall in portable weatherproof hanging tents called portaledges. Alpine bigwall climbing is a much more committing style, considered more “pure” than a “siege” with fixed ropes, and the style that the Japanese had been developing and mastering on long climbs all over the world (they, too, were influenced by the ground-up, no-fixed-rope style highlighted by Royal Robbins in Yosemite in the 1960s, and many climbers from Japan were climbing hard routes on the walls of Yosemite in the 1980s). For both the repeat ascent of the Norwegian Buttress on Great Trango Tower by Masanori Hoshina, Satoshi Kimoto, Takaaki Sasakura, and Masahiro Kosaka, and the solo ascent on Trango Tower by Takeyasu Minamiura, the ascents were climbed in state-of-the-art committing alpine bigwall style, including high-altitude 5.12 free climbing.

I only met with Minamiura for a few hours, but it was super fun, still with the mountain twinkle in his eyes when telling a funny bigwall story or showing the path of his latest 100km+ wild cross-country paraglider flight. Below is the 1990 Trango story written by Minamiura, in his own words:

1. My motivation for the Trango expedition

In the late 80th, there has already been a great progress in free climbing in Japan. Then rappel bolting was accepted among enthusiastic climbers. This style was initially used only to push the extreme limit of free climbing, but soon become used for easier climbs and instantly spread every Japanese crag. I was expecting that other climbers share my feeling about climbing (pushing the limit and the pursuit for adventure), but most of them did not. I felt that the important climbing spirit is being lost and decided to stop free climbing and return to wild and great adventures.

2. Why did I plan to solo and to paraglide.

I naturally chose to climb Nameless Tower that was one of my dream climb since the early days of my climbing carrier. I could not find a partner who has equal amount of experiences in every aspects of climbing as I did. A few possible candidates seemed not to have enough luck. I used to climb with partners, but in a few occasions I soloed long routes in Japan. Cleaning, placing bolts, and working on routes alone in a new crag during weekdays were also my favorite. I think I liked to create something by myself. Soloing is not good for difficult free climbing, but is the best way to enjoy all pitches by myself. To appreciate every aspects of Nameless, l decided to climb solo.

I was also obsessed with the fun of flying in the air by a paraglide that was at the peak of popularity that time. Paragliding has the equal or even more potential as free climbing that appeared to going into dead ends, and gave me the sense of freedom, openness and thrill. Paragliding would also shorten the time of decent (Of course I brought a parachute for throwing the gears down).

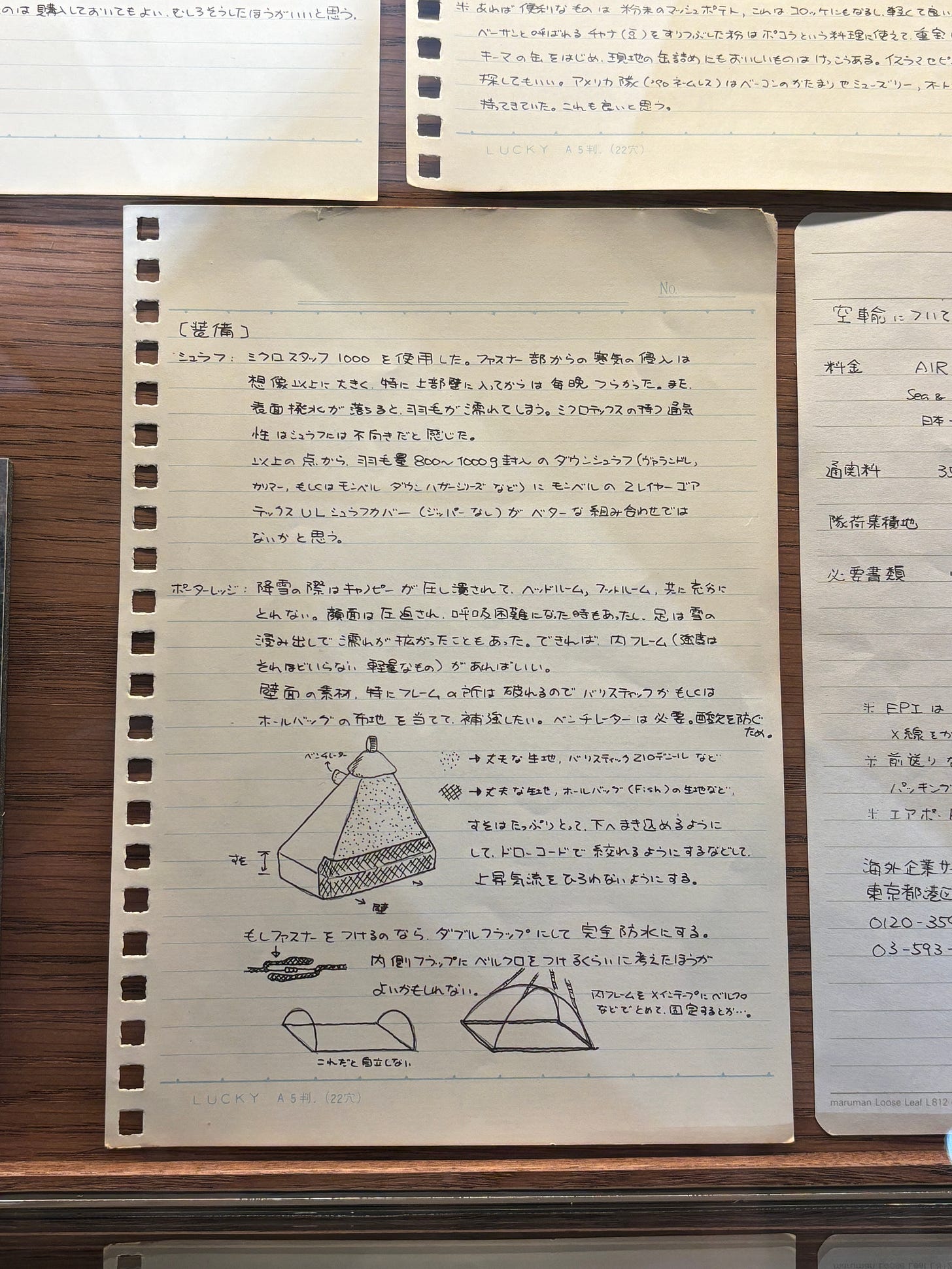

3. Gears and hauling

Full EI Cap rack, Circle copper heads, a few ice pitons, five ropes, two paragliders (one for reserve), a harness for paraglide, variometer, video camera, batteries, tape players, music tapes, films, transceiver. Although I believe my plan was a reasonable one given my experience, I must admit that the amount of my gear was crazy. I hauled 150 kg to ABC placed at the beginning of courier, and 100kg at the start of the climb. I think I should have hired porters at least to ABC. Hauling in the lower wall was very difficult. I ended up in changing the haul line from my own route to Kurtyka-Loretan. Hauling became smoother only after 1lth pitch.

4. Style of the climb

I aimed at one-push capsule style with five ropes but in fact I was forced to retreat once from pitch 11 due to bad weather and to the difficulty in hauling that slowed down the ascent. During the retreat I stayed at the base camp to wait for a good whether and for the return of my friends from the Great Trango. Two weeks later, I returned to the wall for the final attempt.

5. Climbing to the top

We placed the base camp at the base of Dunge glacier on June 23. I reached the summit of Nameless Tower on September 9. Total climbing time was 40 days, among which I bivouacked 21 nights on the wall and 17 days were spent for lead climbing. I reached the top of the lower wall on July 26 after fixing ropes for four days. I tried to haul the gears through my original line for two days (26, 27) without success. After changing the haul line to Kurtyka-Loretan route, I finally pull the haul bags to the top of the lower wall on August 7. From August 8 to 13, I climbed six pitches on the main wall before I was forced to retreat due to bad weather. On August 27 I returned to the climb and climbed additional 16 pitches to reach summit on September 9. Five days during the final push were storm. There was no ledge in my route. The climbing was as if going up a huge chimney. It was really cool to do bold moves in such a great place. I fell four times; one was at the expansion flake in the lower wall. Watching Masherbrum, the mountain that I summited before by Alpine style, was a great encouragement to me. I was very lonely during storms and nights. Falling ice after storms often made holes in my flysheet. During storm, snow that accumulated between the wall and portaledge pushed me out. The route above the pitch 18 was covered with verglass and I had to change my footwear from rubber sole to plastic boots.

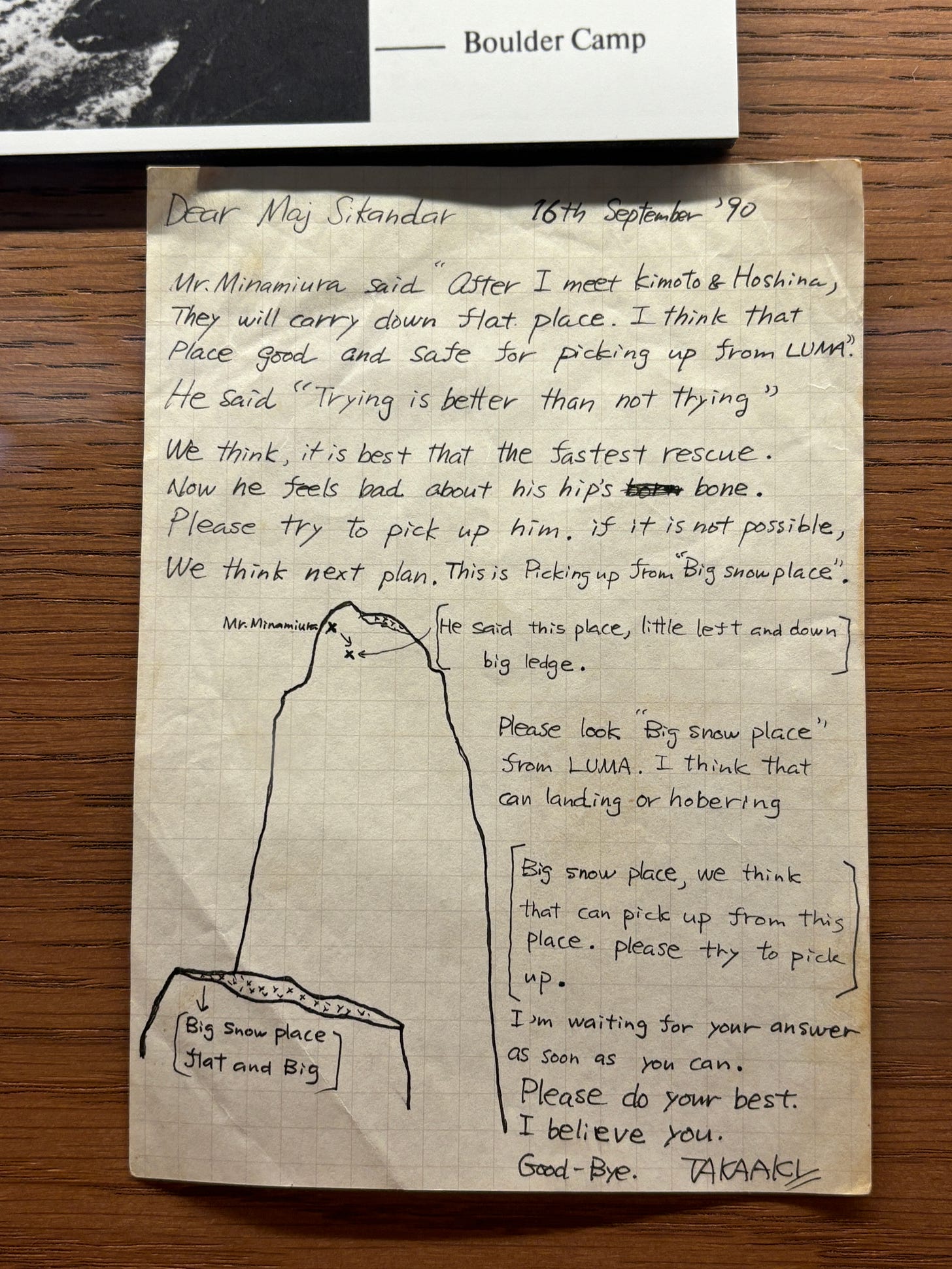

6. The paragliding accident and the rescue (September9-18)

September 9, I rappelled for 20 meters to return to the shoulder from which I planed to take off. The cloud was increasing, showing a sign of deteriorating weather. I knew that once it storms, there would be no chance for take off for a few days. Only two additional meals were left and the sunset was getting closer. The wind that was blowing strong during the day become gradually weaker, and got stronger once again. Unfortunately, the wing occasionally blew from behind. I patiently waited for a chance to catch against wind. Finally the wind become stronger and I released myself from the belay, raised the paraglider and took off for a dive into 2000m of space. Immediately the tension of the paraglide was lost from the right side and I was falling upside down. I knew was caught by the tail wind. During the fall I tried to convince myself that I am in bad dream. But at the next moment a strong shock struck me at the back and reminded me the reality. I was hanging in the space. I could not breath well due to the pain and could not even look up to check how my paraglide caught the fall. Ironically the variometer showed only a loss of 45 meter. Fortunately my transceiver was working and I call my friends to describe my situation while panting. I thought I should keep my pride, so instead of asking for "help" , I told them that I had an accident and need a helicopter. My ice ax protected my back from breaking. Some films were broken and the headlamp was smashed. Eyeglasses were lost. Soon darkness came in and I had to wait for the Morning while hanging in harness.

September 10, I looked up in the Morning to find that a tiny flake held my paraglider. I found a small ledge and carefully traversed 5 meters of third class to move myself to the ledge where I ended up staying for six days. I sat on the ledge that was a feet and four inches wide and covered my body with the reserve parachute. There was no way to belay myself, only the void was below me. I waited for helicopter. If helicopter can come, it should be able to lower my friends Masanori Hoshina and Tetsu Kimoto to the shoulder where I took off. I hoped that they should be able to pull me up to the shoulder.

September 11, "Helicopter can not maintain the hovering position at 6000 meter " ; I was told that it was impossible to rescue me with a helicopter. I was desperate, but immediately regained morale. I could die at any time, all I needed was to lean myself a little bit forward. I decided to wait for two of my friends to come rescue me as long as possible. In case they could not come, I had a choice to base jump with the reserve parachute which I was using to protect myself from cold. But I knew that the chance of success was nil, and saved this for the last resort.

September 12, the helicopter dropped food and first aid kit, but I could not catch any of them. A pack of mango juice crushed in front of me, leaving the smell and a few drops. It made me laugh rather than to be disappointed. Sunshine wormed me up until three PM and I could get some sleep. I awoke all night, massaging each foot while waiting for sunrise. My foot became numb with even a short nap. I tried to protect my foot from frostbite because I didn’t want to give up my rock climbing skill even if I survive. When I could not stand for coldness and hanger, I called Takaaki Sasakura at the base camp. We mostly talked about foods we wanted to eat after returning to Japan. My desire for food did not stem from hanger, but rather from an escape from the reality. Thirsty become stronger day by day, but my body refused eat ice.

September 15, helicopter came again for the first time since 12, but the dropped food disappeared the same way as the last time. When I was disappointed, good news arrived. They told me a can of cheese was caught at the flake that was holding the paraglider. To get the cheese, I had to climb 5 meter up, and once I moved there, probably I cannot return to this ledge again. Now that I was exhausted and it was difficult even to stand at the ledge. I have chosen to take the risk and decided to move to the upper flake. I immediately found the cheese and ate food for the first time in six days. It was clear now that the place was good for dropping foods: the helicopter came again in the afternoon to drop a few more canned foods. When I have filled my stomach, I found the rescue party 20 meters away at the same height. Hoshina and Kimoto reached there in only three days of climb through the original route by risking dangerous pitches.

September 16, met the rescue party, bivouacked at the same place. September 17 rappelled down the Yugoslav route to the top of the lower wall. September 18 Returned to the ground.

Takeyasu Minamiura

Pictures from the exhibition:

Trango 1990 Solo Ascent

Great Trango 1990 ascent

Timeline of the 1990 Trango Towers Expedition (translated roughly by Google):

Letter from Takaaki (2005):

Dear John Middendorf

Thank you for getting back to me.

We (masanori Hoshina,satoshi Kimoto,masahiro Kosaka and me) made NORWEGIAN route on NE-piller of Great TRANGO In 1990 summer. It took 27days after GOING-UP from DUNGE Gl with "capsule style". After that climb,our friend takeyasu MINAMIURA attempted new route on the NE-face of the NAMELESS by himself. He made It and jump-off from tne top with palagrider but failed. Paragrider was hook rock ,about 80m below the top of the tower. He yelled "falling !! " by woky-talkey(radio). Fisrt we tried to contact paistan-army and ask them heli-resucue But they could not. Because too high alltitude very thin air. So they saied " If you wanna help him,you have to climb up by yourself" We, I mean masanori HOSHINA,satoshi KIMOTO and me,made tactics about rescue. That was HOSHINA and KIMOTO climb the BRITISH route and I backing-up them. Why BRITISH route? We thought that this route was sound line because first assent route of this Towr in 1976 by JO BROWN as we remember . HOSHINA and KIMOTO move to from DUNGE GL. To TRANGO Gl. By helicoptor. I hiked up to advanced base camp at DUNGE Gl. Took gear and carry to TRANGO Gl. By foot all the night. And then I catched up them next evening at near by bottom of NAMELESS. I gave the gear to them. They took 2days and half to reach place at MINAMIURA. Then they rappel to the bottom. Nine days all together , complete to rescue.

Anyway after TRANGO in 1991 ,MINAMIURA ,HOSHINA and me went to YOSEMITE and made NOSE and SHIELD . MINAMIURA and HOSHINA made SOUTH-SEAS to PO-WALL, HOSHINA made LOST In AMERICA with his friend same year. I went to there again and have done COSMOS with my friend In1994. I used "A5" porta-ledge ,rope-bucket and Dasy-chains all climb In yoemite. That were great!

With best wishes ----------------------------------------- Takaaki sasakura

For more information on Trango Tower ascents, see:

It was so nice to also meet: Ishiguro the Tiger, Nonako Reiju, Masakatsu Horie, Yuya Nakayama, and many others! And of course to present with Naoe Sakashita.

Mind-blowing documentation of mind-blowing spires and peaks, John. Wow. (And so cool, that Rowen went with you.) Seeing Xaver's name, of course...well, those of us still here have feelings. Two who easily could not still be among the living, having done what you did on Trango: That Minamiura & Middendorf photo is priceless!