Mystery Mountain, part 1 (1922-1934)

Mechanical Advantage Tools for the Wild Vertical drafts

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

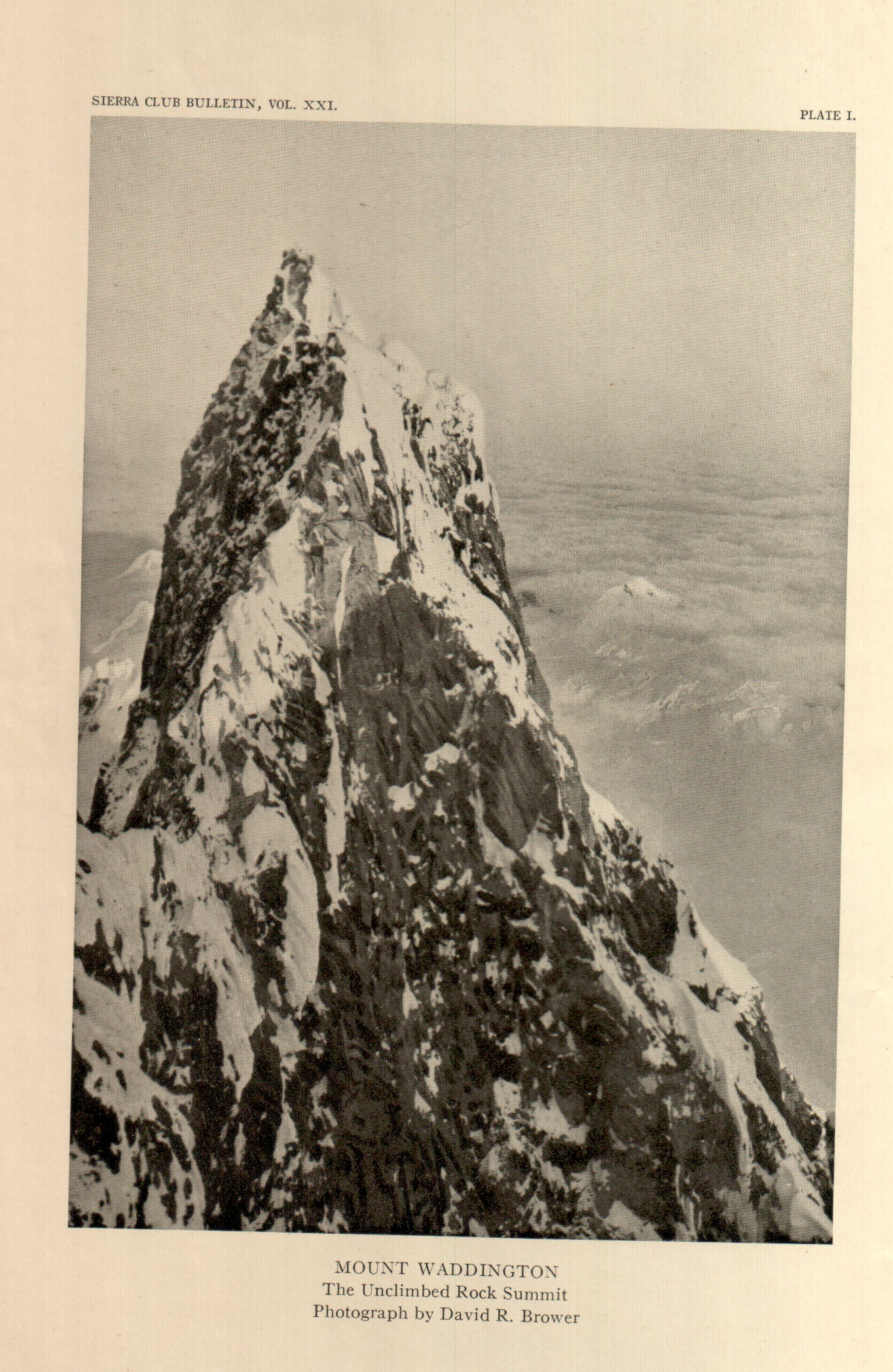

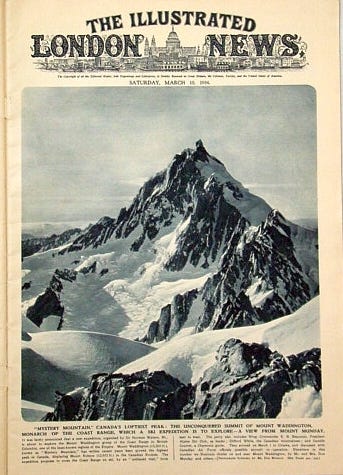

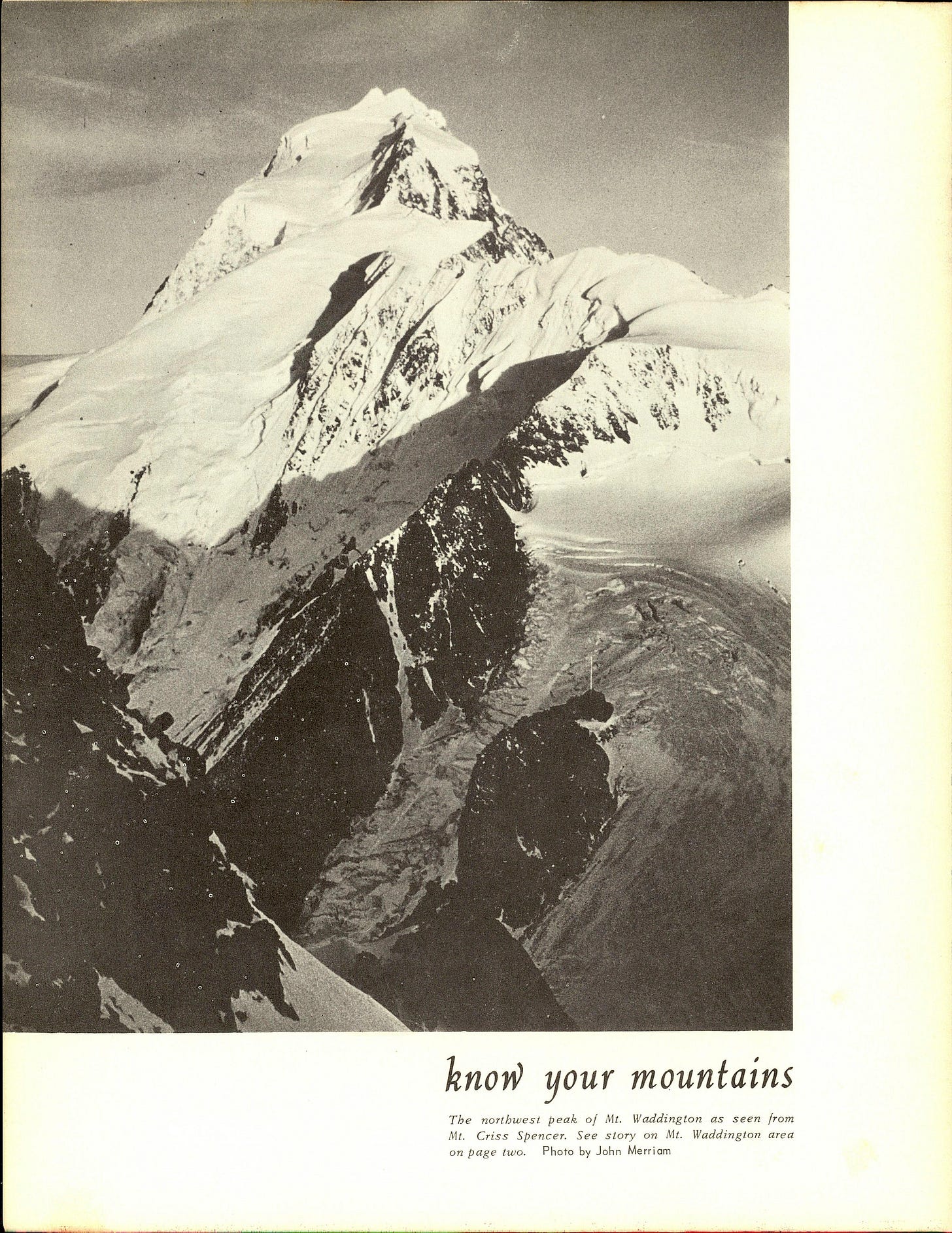

Mount Waddington aka Mystery Mountain, Coast Range

Early sightings and attempts

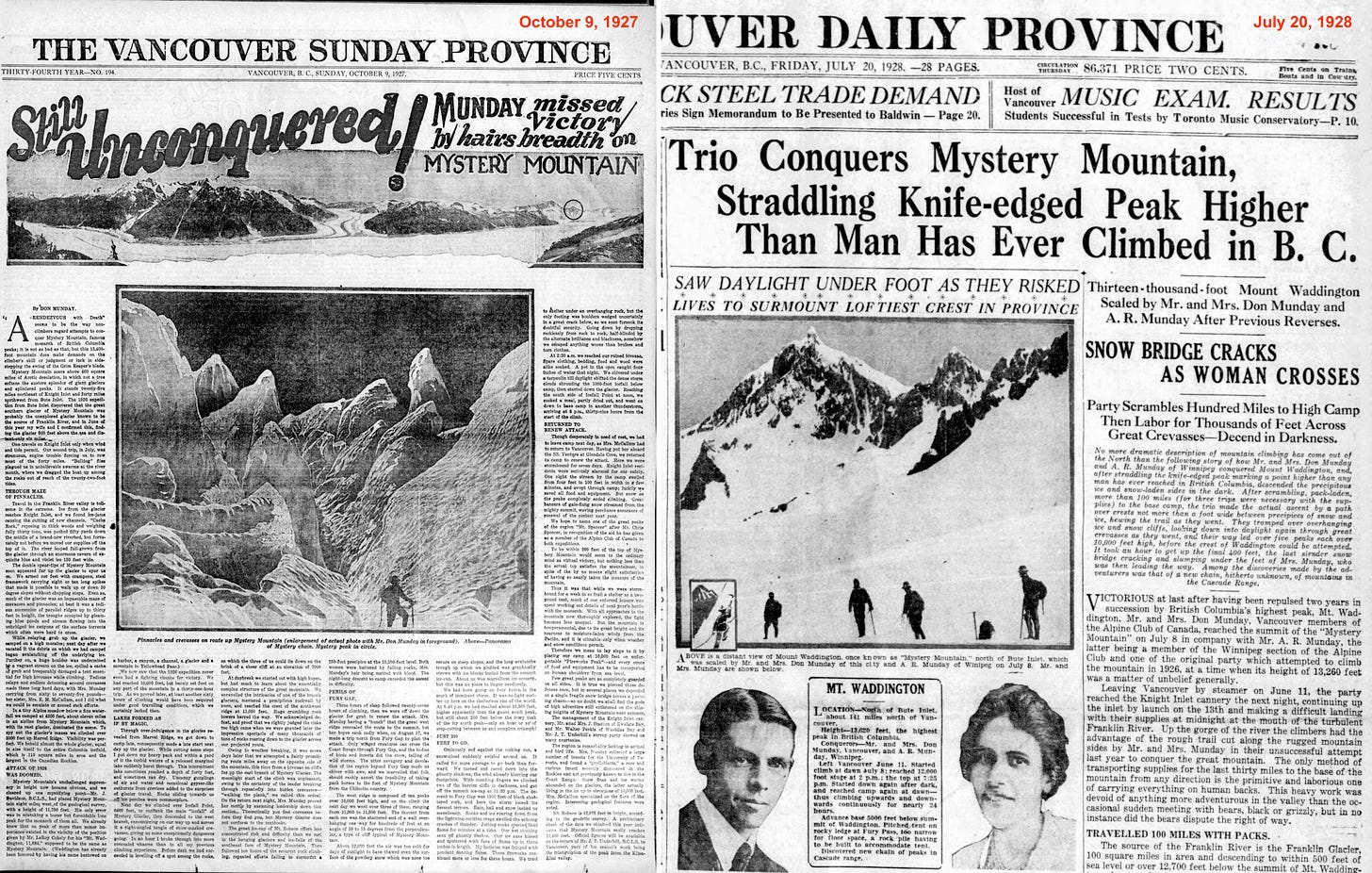

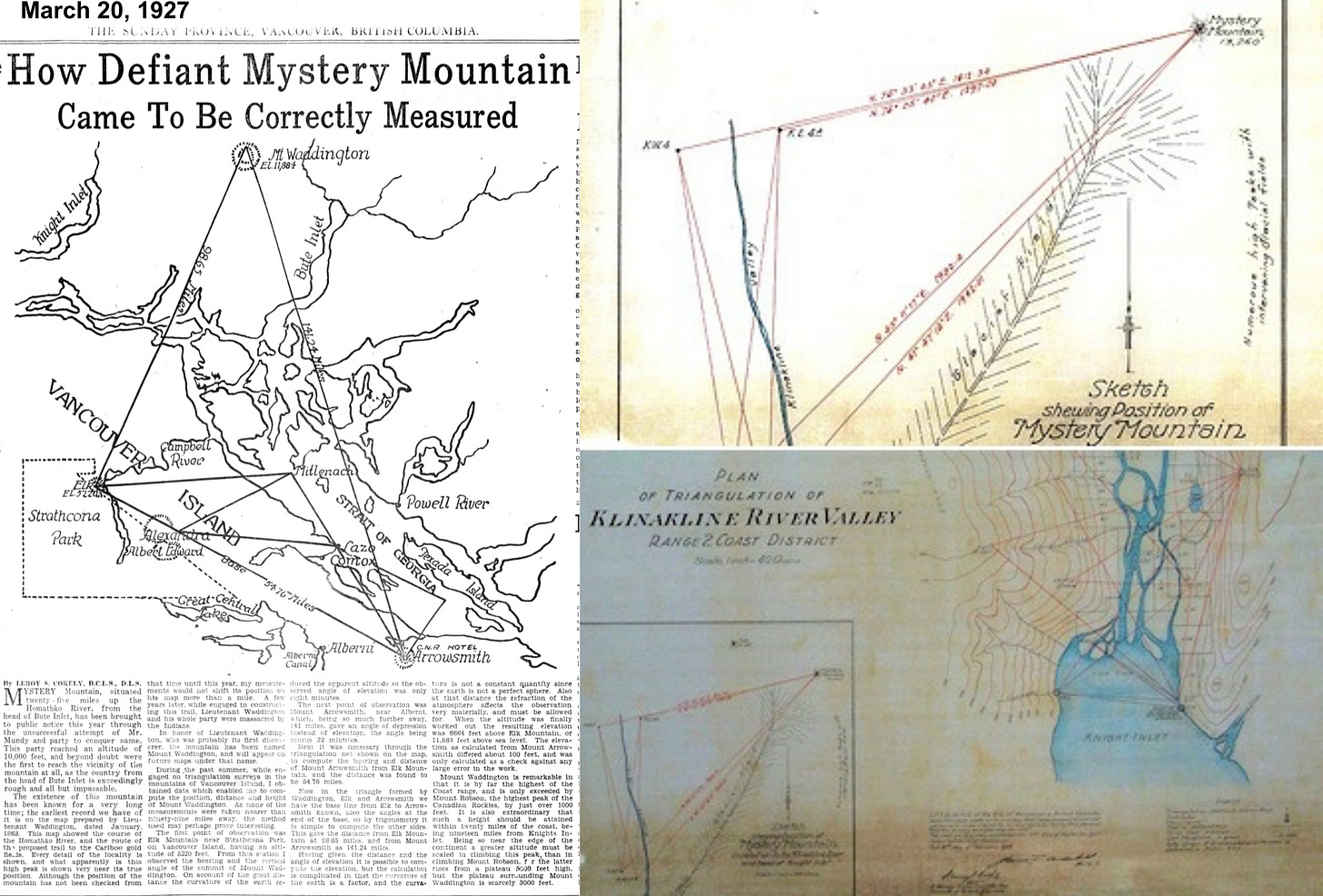

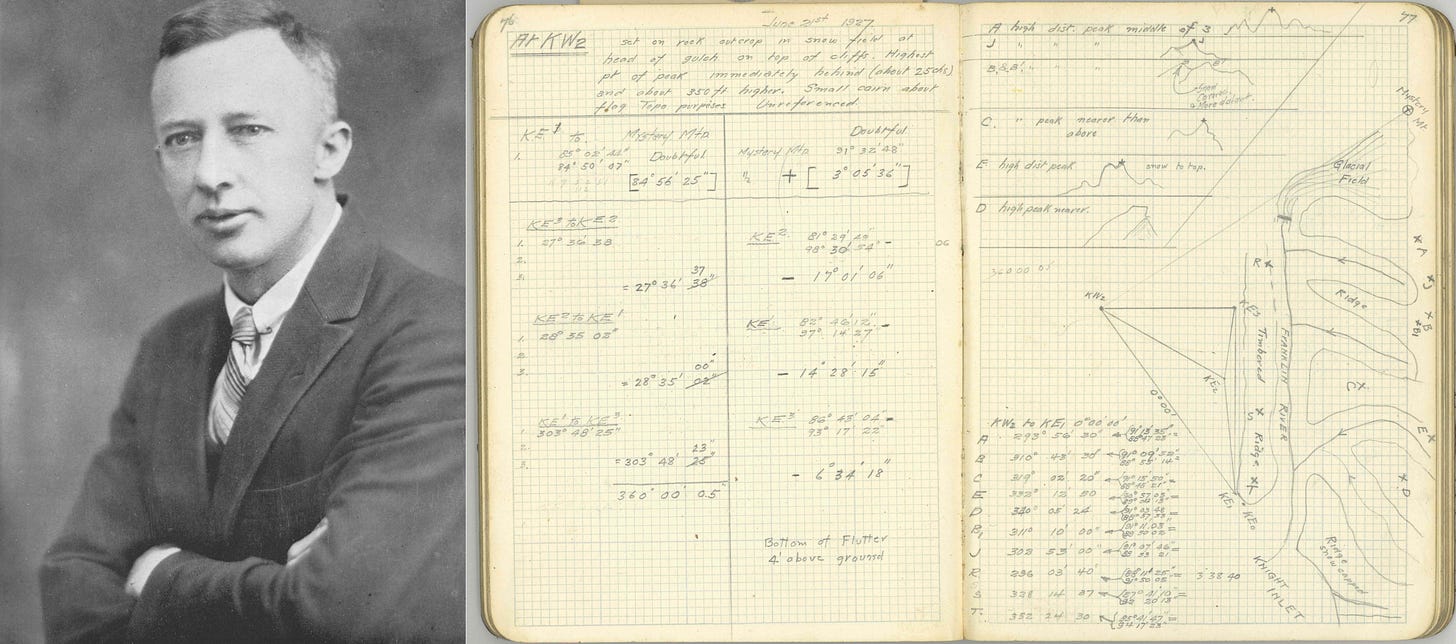

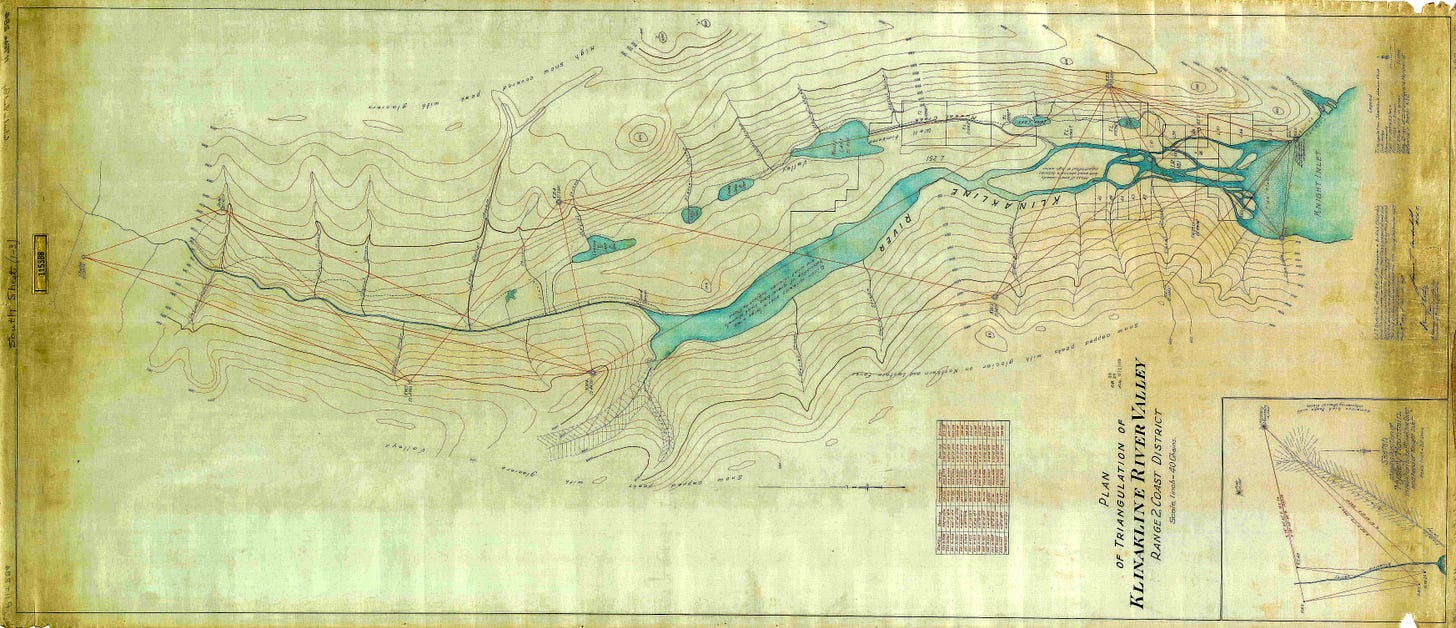

In 1922, while carrying out topographic surveys near Chilko Lake, Captain R.P. Bishop sighted “a peak of great height” in an uncharted region of the Coast Range. The next year, working with Victor Dolmage of the Geographic Survey of Canada, they estimated that the unnamed peak was over 13,000 feet tall. Reports of this discovery “fired the enthusiasm of two Vancouver mountaineers, Mr. and Mrs. W.A.D. Munday, who organized an expedition to conquer this new monarch of the Coast range” (The Province, Jan 15, 1928).

In 1924, Don and Phyllis Munday climbed Mount Robson (with Conrad Kain on a ACC camp), which was then believed to be the highest point in British Columbia, and in 1925 the couple began a decade of effort to climb this “peak of great height” in the Coast Range. They initially sighted the range from Mount Arrowhead on Vancouver Island, 140 miles distant, then climbed to high points above Bute Inlet, 50 miles distant, to gain a grasp of the challenge and to get a closer look at the range’s imposing centerpiece that became known as “Mystery Mountain” (also known as Mount Mystery or Mystery Peak). Surrounded by impenetrable bush and treacherous glaciers on all sides, access into the range would prove a formidable challenge.

Footnote: many uncharted mountains were called ‘Mystery Mountains’ in this era, including Mount Everest in 1920, known to be the highest peak in the world (but still a mystery of access), the unmapped ‘Bunya’ range in Australia in 1919 (“Queensland’s Mystery Mountains”, despite being well known by Indigenous people), and ranges like the Dzhugdzhur Mountains in Siberia and the Mountains of the Moon in Africa, noted on early maps but not yet known by foreigners. Basically, any ranges not well known by Europeans were often coined “Mystery Mountains” in this era.

In 1926, after an epic struggle bushwhacking through devil’s club and alder bush from the east via the Homathko River (noted as the “Terror of the North”), the Mundays traveled up the eastern glaciers to the southern ramparts, deeming the south wall “out of the question,” and unsuccessfully attempted the southeast ridge of Mystery Mountain.

In 1927, they discovered an easier approach from the south via Knight Inlet, and attempted the northwest ridge, getting caught in a fierce electrical storm and aptly naming their highpoint, ‘Fireworks Peak’ (one writer later headlined the story, “Storm makes human torches of alpinists.”)

In 1928 the Mundays returned (with Don’s brother Bert) via the southern route and successfully climbed to the northwest summit, which some papers reported as the “conquest” of the mountain, even though the main summit was clearly higher. The Mundays continued to make several more attempts from various directions over the next five years, but as they considered the southern flank unclimbable, they were unable to find an alternate route to the top of Mystery Peak, though their first ascents of many other summits in the range were also considerable challenges.

Highest Peak

After its initial sighting in 1922, various surveys had attempted to measure the height and location of the peak, but it was not until January 1928, when the 1927 annual report from Canada’s Department of Lands was made public, that the official height of the peak was announced to be 13,260’, and thus higher than Mount Robson, previously thought to be the highest in the Rockies and the Coast Range.

The naming of Mount Waddington

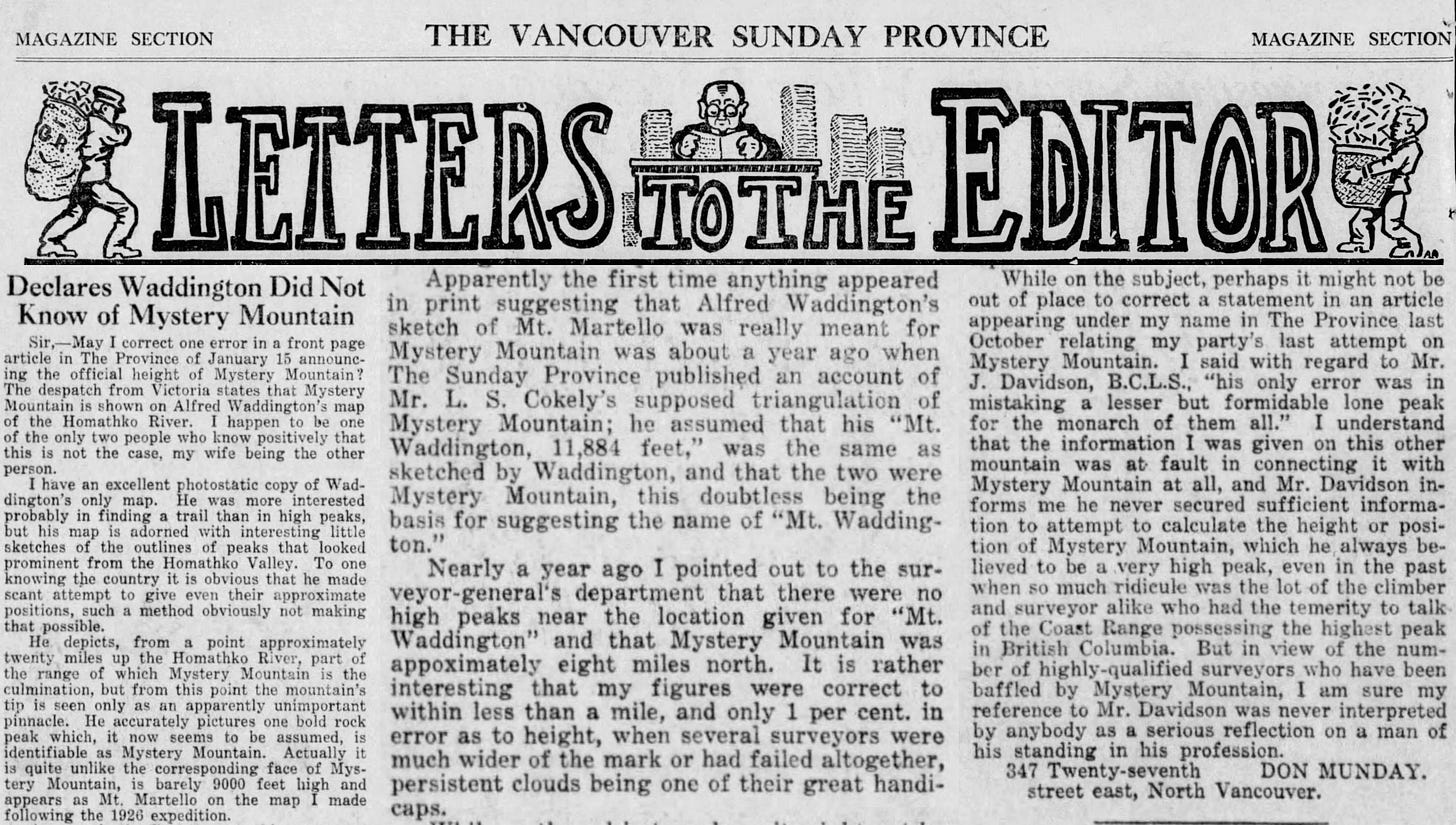

As the peak became famous as the highest in British Columbia, several articles in newspapers reported that Alfred Waddington, an early Canadian explorer, had noted a peak of “extraordinary height near the head of Jarvis Inlet” and that he had noted a mountain on his 1862 sketch maps corresponding to the position of “Mystery Mountain”, and thus deserving of the mountain’s name. Waddington first came to the area during the Fraser Canyon and Cariboo gold rushes and had attempted to construct a wagon route from Bute Inlet to the Cariboo goldfields on the eastern side of the Coast Range, an incursion into indigenous lands that created conflict with the Tsilhqot'in Nation in what became known as the Chilcotin war of 1864 (aka the Bute Inlet Massacre, as the leaders, believing they were attending peace talks, were first arrested, then executed).

Footnote: The traditional territory of the Tsilhqot'in includes most of the drainage of the Chilcotin River and the headwaters of the Homathko, Kliniklini and Dean Rivers flowing westward through the Coast range. In 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau formally apologised to the Tsilhqot’in people for the wrongful conviction and hanging of the chiefs (CanadianEncyclopedia.ca). In 1858 Waddington published The Fraser mines vindicated, or the history of four months (Victoria).

As the name ‘Mount Waddington’ gained traction with the Geographic Board of Canada, several letters to the editors in the newspapers objected, suggesting that retaining the name “Mystery Mountain” was more fitting for the inaccessible and as-yet-unclimbed peak. One wrote that visitors “would be more likely to take a trip up the coast to see ‘Mystery Mountain’ than he could to see ‘Mount Waddington’—imagination counts both in publicity and advertising”. Don Munday, based on his extensive exploration and mapping of the region, made a clear case that Waddington had likely never seen, and certainly had not mapped the peak.

Footnote: Regarding naming, Dr. Glenn Woodsworth clarifies: “Very cool indeed. Based on what I know this is pretty accurate. The naming thing was a bit of a dust-up between provincial and federal forces, as I recall. Other names that were proposed included "Mt George Dawson" (for G.M Dawson, the great Canadian scientist, Dawson in the Yukon, Dawson Range, etc.) and "The Unknown Soldier" to try and preserve a bit of the "Mystery" theme.”

Despite the questionable naming, once it was discovered that the highest mountain in British Columbia was a little-known peak that some still preferred to call Mystery Mountain, it was not just the Vancouver alpinists who became interested in its ascent. The mountaineering world took notice, and the unclimbed challenge was broadcast on both sides of the Atlantic. The writer initially reporting on the official survey in 1928 predicted, “Now that the mountain is established as the highest in British Columbia, it is expected to excite keen rivalry among Canadian and foreign engineers with a view of achieving the first ascent.” Over the next eight years, it became the most coveted unclimbed summit for North American aspirants, and mountain climbers, alpinists, and rock climbers all came from far and wide.

Tools of the Trade

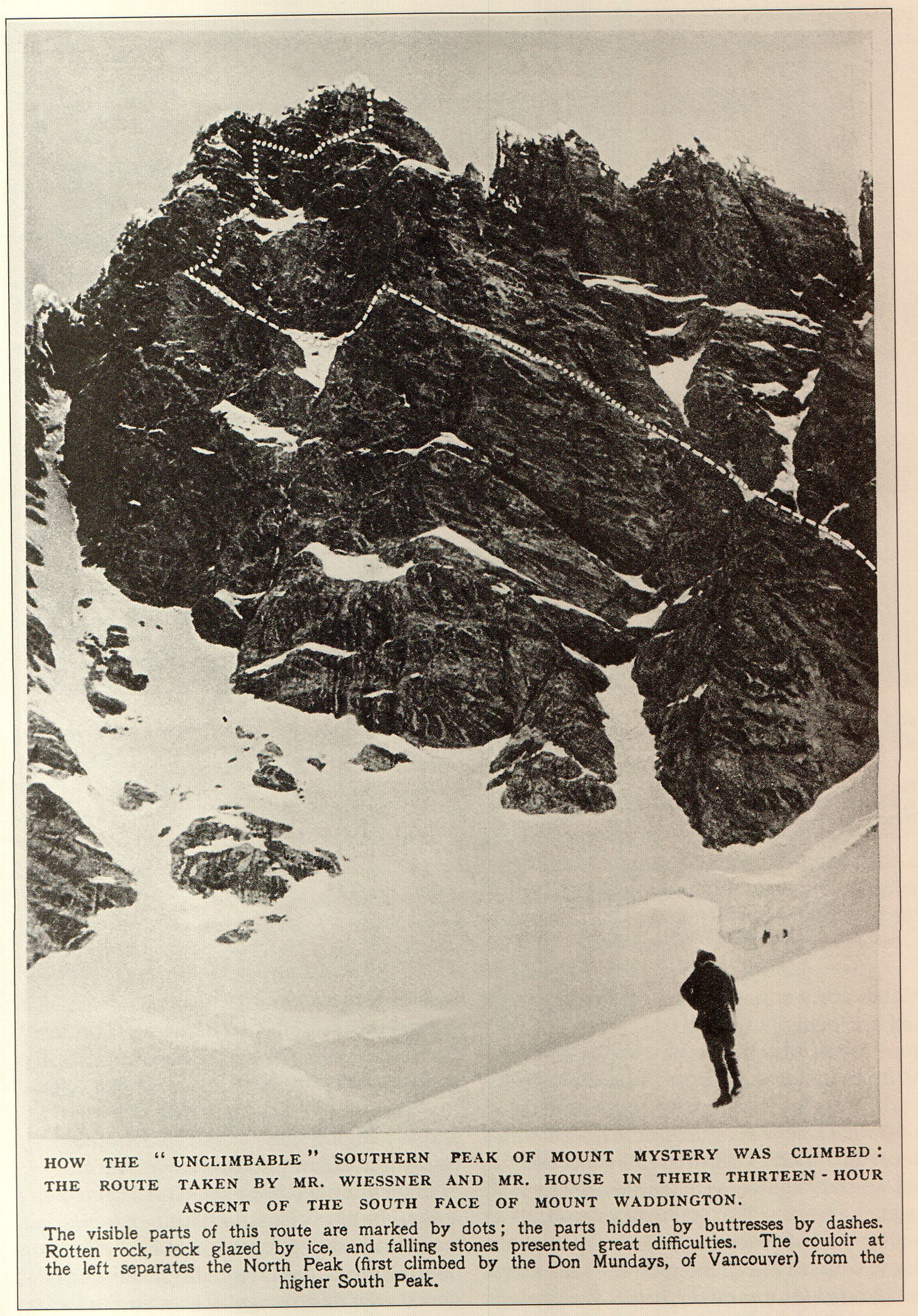

Skills and tools—machete, long ice axe, skis—that the Munday’s had mastered were essential in their approach and many climbs in the region, but they were insufficient for a long alpine mountain rock climb like Mount Mystery. Chasms were crossed with engineering prowess using felled trees, glaciers were traversed with expert roping, and steep ice faces were ascended in nailed boots and chopped steps, but even though the Mundays were also bold on rock, the steep buttresses and faces of Mount Waddington required climbers who had practiced and acquired more advanced rock anchoring skills and tools.

The Mundays and the B.C. Mountaineering Club were generous with providing assistance and information to the visiting climbing teams that came to try their luck on Mount Waddington. Henry Hall of the American Alpine Club initially believed the solution was from the north to gain the southeast ridge, but after three forays between 1931-1934, finally deemed the rock tower of the main summit “next to unclimbable”. A Canadian team from Winnepeg (Ferris Neave, Roger Neave and Campbell Secord) also approached from the north, and armed with pitons (perhaps only used for retreat), came within a few hundred metres to the summit via the southeast ridge in 1934, but were thwarted by the final headwall. The same year, Alec Dagleish died on the southeast ridge after approaching from the south; meanwhile, Norman Watson, E.B. Beauman, and the Chamonix guide Camille Couttet crossed the range from north to south on skis. The mountain was deemed impossible by most who had seen it, and several teams were content to repeat the route to the northwest summit, and the preferred approach became the route from Knight Inlet, as the thick bush initially cut by the Mundays in 1927 (a cabin was also built) had by now become a “usable trail” to approach the Franklin glacier and the mountain’s southern ramparts.

NEXT (part 2)

1935—Sierra Club attempt: Bestor Robinson, Jules Eichorn, Richard Leonard, David Brower, Jack Riegelhuth, Don Woods, Bob Ratcliff, Bill Loomis.

1936: Sierra Club/Alpine Club of Canada/British Columbia Mountaineers combined attempt: discussions and debate on risk and potential lines of ascent.

1936—American Alpine Club East Coast success—House and Wiessner (w/ Jack Tackle piton collection, and other Bill House USA-made pitons). [p.s. realized I have been spelling Wiessner incorrectly—has been corrected in Volume 1].

1942: Helmy and Fred Beckey ascent (at age 16/17 and 19).

Thanks to Don Serl (noted Mount Waddington expert), Anders Ourum (honourary member, BCMC) and Chris Cryderman (of J.T.Underhill Geomatics) for revisions to this piece.

Appendix Images

the "what if" picture in this series is of them looking at Mount Queen Bess from Homathko or Endeavour. Not the Wadd Range at all, but northeast across Homathko River and Moseley Creek about 40 km away.