Mystery Mountain, part 2

draft for Tools of the Wild Vertical, by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Sierra Club attempts, 1935-1936

After climbing the ‘impossible’ summits of the Cathedral Spires in Yosemite, the Sierra Club rock climbers heard of the Mount Waddington attempts. Richard Leonard reflected, “After we read in the newspaper that some British and Canadian climbers had been trying to climb Mt. Waddington, the highest peak of provincial Canada—they had made ten attempts, and all ten had failed. So we said, ‘Gee, it is time that we went.’ It was a rock climb, so we figured we could rock climb there as well as anywhere else.”

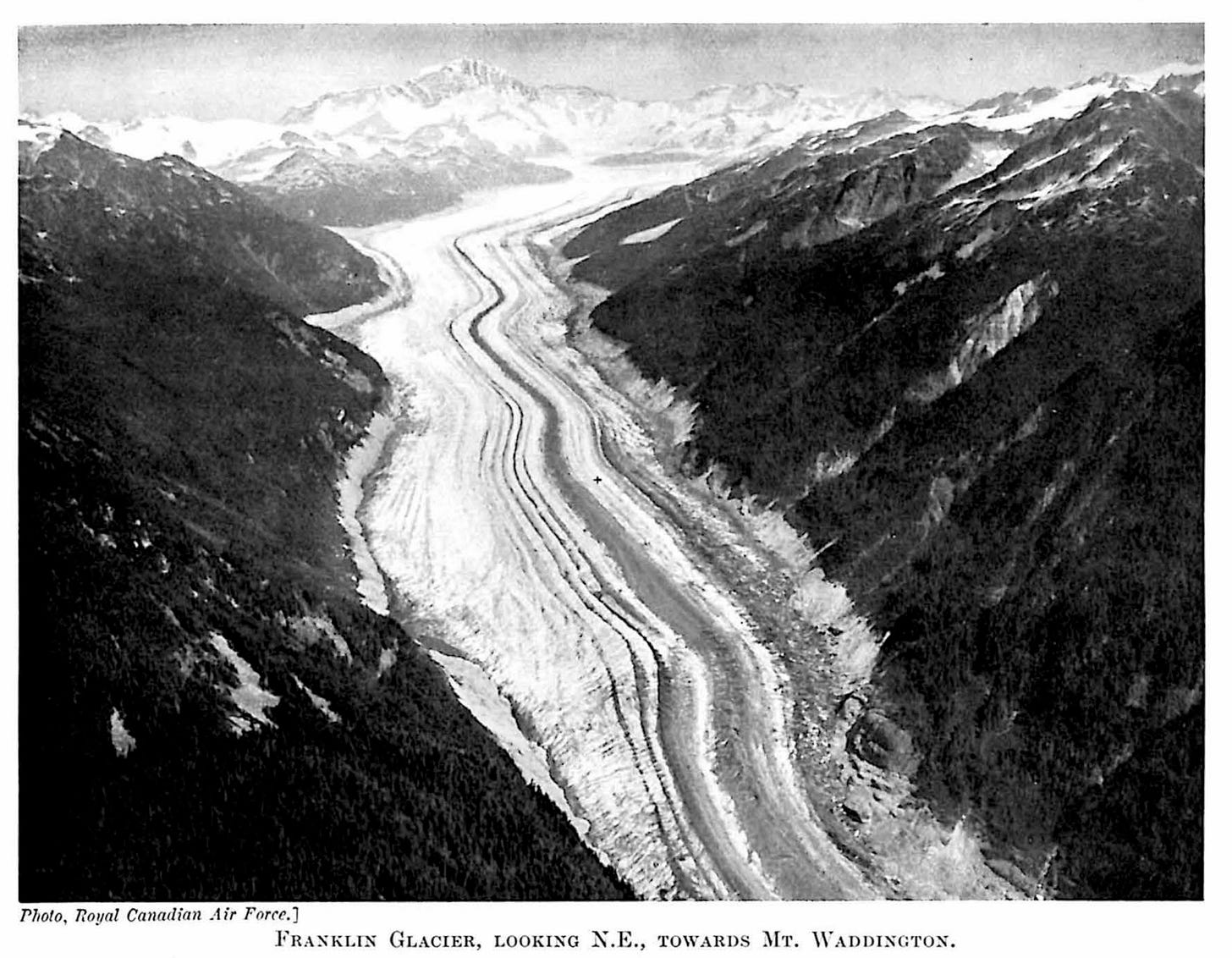

A team of eight was assembled for the challenge: Bestor Robinson, Jules Eichorn, Richard Leonard, David Brower, Jack Riegelhuth, Don Woods, Bob Ratcliff, and Bill ‘Farnie’ Loomis (the latter from the Harvard Mountaineering Club). While their Sierra Nevada climbs had honed their rock climbing skills in high alpine conditions, they soon realized that the Coast Range's rugged and glaciated mountains posed a significantly greater level of remoteness and exposure to risk. Leonard describes the first attempt in 1935: “We had to go up a twenty-five-mile glacier, starting at three feet below sea level. We had a seaplane and got out of the plane in salt water and started the climb up this twenty-five-mile glacier to reach the snow summit at 13,000 feet. At that point, a very severe storm came in, and we had to retreat in the blizzard because of avalanches and couldn't make the rock summit.”

The 1930s marked a period of significant expeditions in the Himalayas, following the first attempt at Everest in 1922 (footnote), and perhaps inspired by the progression of larger teams as a key strategy for the ‘big jobs’, the 1935 Sierra Club attempt of Mystery Mountain was tooled up to the gills. Bestor Robinson lists some of the 800 pounds (363kg.) of equipment the team loaded onto two floatplanes to fly them to Knight Inlet: “There were one hundred and twenty pitons, seven hundred feet of rope, carabiners, piton hammers, crampons, ice axes, snowshoes, tents, sleeping bags and the hundreds of other items necessary for a self-sufficient expedition.” The team planned for three weeks in the range, with a daily food ration of 2.5 pounds (1.1 kg) per person.

footnote: Robinson also relates the technique of carrying heavy hardware on one’s person to avoid baggage limits for the Canadian Airways flight, a tried and true technique of many future expeditions. Expedition tools and techniques—clothing, cook systems, ice gear, tents, the quest for lightness, etc.—will be covered in another section of this volume, featuring Paul Petzoldt’s innovations, especially as to how the equipment was essential crossover gear for remote bigwalls and vertical living.

The Sierra Club rock climbers were unabashed in their reliance on pitons, having climbed the Higher Cathedral Spire in 1934 with a rack of 55 pitons and 13 carabiners. The 120 pitons they packed for their Mount Waddington expedition signaled their expectation for even greater difficulties and considerable aid. Their climbs in Yosemite had required only short sections of aid, but the Coast Range terrain was less familiar. As team leader Bestor Robinson noted, “The Bavarian two-rope technique for overhangs, pitons for direct aid, rope traverses, and other phases of technical rock climbing will probably be necessary.”

footnote: For the “Bavarian two-rope technique” see Volume 1 for more on the various aid techniques, the 2-rope system basically uses one rope held in tension by the belayer to hold the climber in position while placing the next piton as the winch point for the second rope. Variously called the “Munich technique” and a number of less polite names. Single-step aid ladders were sometimes used (or a sling), but multi-step aid ladders used in Europe had not yet become a “Yosemite technique.” As discussed previously, the mild-steel pitons were often removed for future use, but often did get fixed in the hard Yosemite granite. In the gneissic-schist of Waddington, the soft steel pitons would have been more easily removable (mostly because the placements are generally not as solid).As a rack size comparison, the initial 250m of steep overhanging limestone of Cima Grande required 75 pitons in 1933, where big aid climbs had advanced much earlier than in North America.

The Sierra Club team’s vision of a direct line up the south wall was daring, but it wasn’t their expectation of a hard aid route and a large rack of pitons that was their undoing. Granted, there were only short spells of decent weather during their attempts in early July 1935, but they made some critical errors in strategy. They established their base camp low on the eastern side of the Dais Glacier, 6000 feet (1800m) lower than the summit, requiring an initial 3000-foot ascent up the Dais icefall to the base of the rock for each attempt, likely requiring a bivouac and extended periods of decent weather. More critically, they opted for relatively safer and steeper rock lines directly up the south wall, rather than risking the snow and ice couloirs on either side in order to quickly gain the upper headwalls. After several attempts, thwarted by weather and time, five members of the team snowshoed up to the NW summit, their high point for the year.

The next year, the Sierra Club was back, this time a combined expedition with the British Columbia Mountaineering Club comprised of 15 people (footnote). With 1200 pounds (545kg.) of food and equipment, and multiple teams trying various lines, they were no more successful in 1936. The first ascent would require a more lightweight alpine approach, a smaller kit of climbing gear, and the willingness to accept additional risk.

footnote: Under the joint leadership of Bestor Robinson (Sierra Club) and William Dobson (BCMC), members from the Sierra Club on the 1936 attempt included Jack Riegelhuth, Kenneth Adam, Hervey Voge, Bestor Robinson, Richard M. Leonard, and Raffi Bedayn. From the BC Mountaineers: William Dobson, James Irving, Elliot Henderson, and William Taylor. Lawrence Grassi, of the Alpine Club of Canada, was also on the team. Kenneth Austin, Denver Gillen, and Donald Baker from Vancouver worked as packers. Arthur Mayse, a reporter from the Vancouver Province also accompanied the team, along with twelve carrier pigeons to relay information to Vancouver (In an interview with Dougald MacDonald in Climbing 87, Bill House later said of the pigeons, “I don’t think any of them made it”). Anders Ourum notes that the BCMC president Roy Howard, in exchange for the help he provided to the Sierra Club, received “a whole bunch of carabiners and pitons. I was probably the first in the mountaineering club to use pitons.” (Anders also notes that Mount Fairweather is actually the highest point in provincial Canada, being half in B.C.)

In 1975, Richard Leonard reflected on the Sierra Club attempts: The easiest way to climb that side of the mountain was up what they call a couloir or gulley--a chute 3,000 feet long at an angle of about 65 degrees. Any rock or ice would come down that gulley so fast that you couldn't even see it. It would zoom, zoom, as it went by. We stayed out of it because we decided that it wasn't safe. There was nothing you could do about those falling rocks except not to be where they were. That is why we stayed out on the steep ridges, but the climbing was so slow that we weren't able to make it. Another party from the American Alpine Club made it the same year we were there. They climbed up the dangerous route and had a very severe rock fall during the dark: they couldn't see it either and were just lucky they weren't hit.

Footnote: From Wiessner’s point of view, after his and House’s successful ascent, the risks were calculated: Under no conditions would I abandon the principles of 'safety first' and would never indulge in an uneven match with objective dangers, no matter how desirable the goal might be. (1937 Alpine Journal).

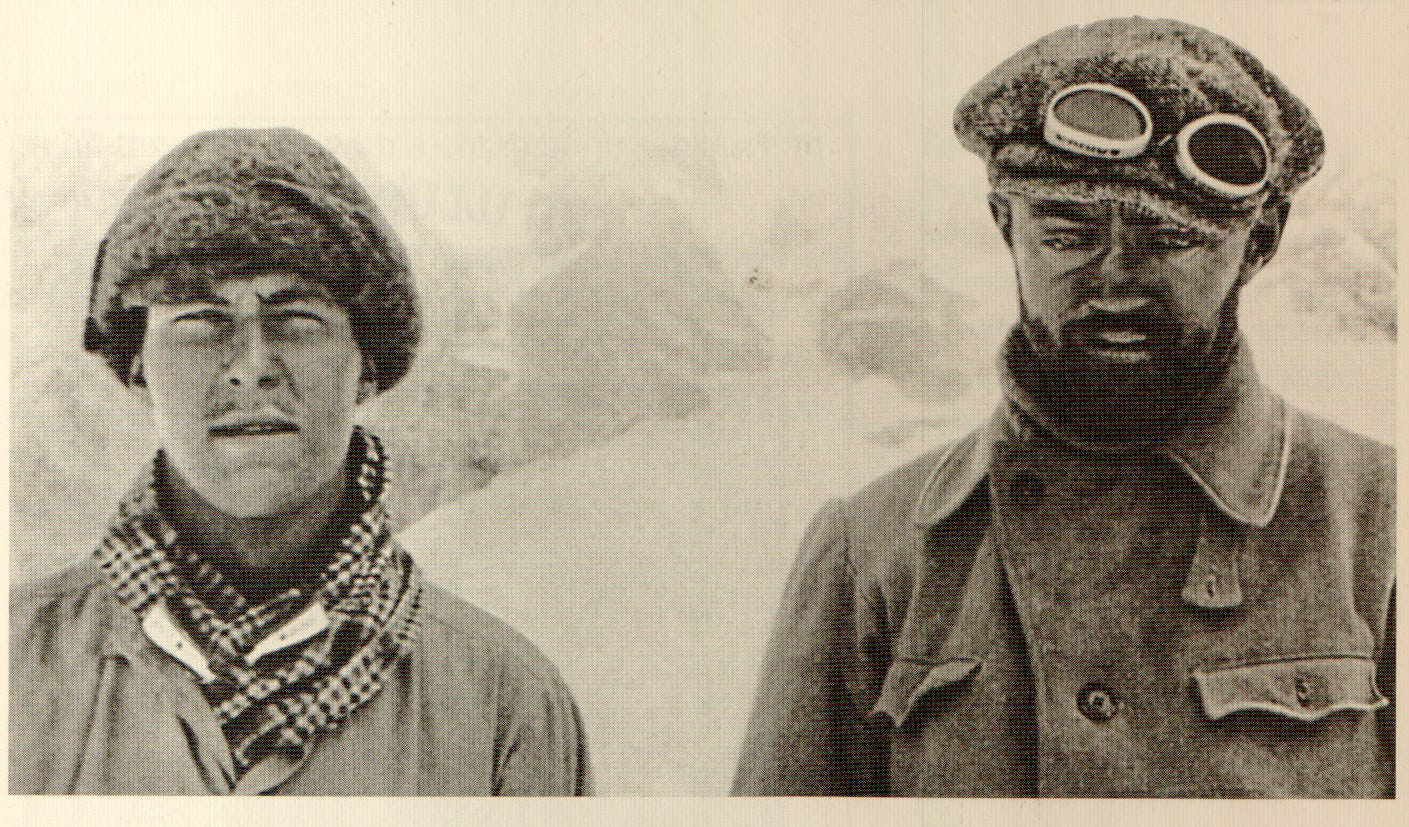

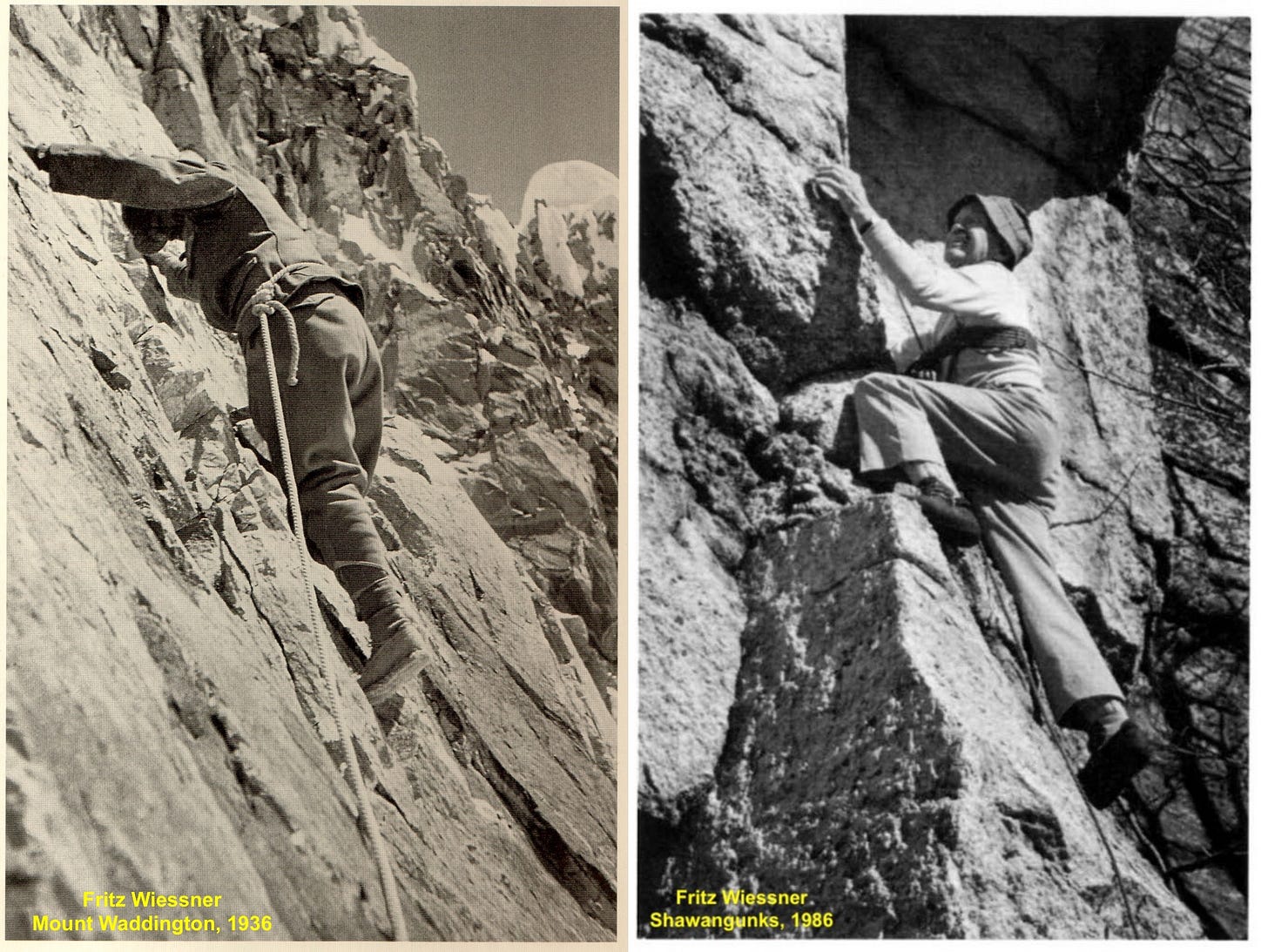

Enter the Wiessner/House team

Fritz Wiessner (1900-1988) needs no introduction to students of American climbing, who established many of the hardest climbs on the crags of the East Coast in the 1930s, often demonstrating the expert use of pitons to protect bold free climbing. Prior to his immigration to the USA in 1929, his level of climbing on the sandstone cliffs near his hometown of Dresden (see Oliver Perry/Elbsandsteingebirge notes in Volume 1) was several grades above the USA standard at the time (~5.9 vs ~5.7, though not always comparable as styles varied and human assistance was not considered aid). Also in his repertoire of experience were some of the longest mostly free walls in Europe, and a bold early attempt on Nanga Parbat on the joint American-German expedition of 1932 reaching 23,200’ (7070m). In the 1930s, Wiessner was developing new alpine ski waxes and was a member of the American Alpine Club, based in New York.

William Penrose House (1913-1997)

Bill House, 13 years Wiessner’s junior, was a young protégé. Born in Pittsburgh, as a teenager he climbed (with a guide) the Dents du Midi during a family holiday, soloed cliffs near his high school (Choate), and in 1932, climbed the Grand Teton, which by this time had become a rite of passage for American climbers. While studying at Yale, he became well-versed in nighttime building climbing (inspired by the post-curfew British university ‘roof climbing’ tradition), and in March 1934 journeyed into Huntington’s Ravine in New Hampshire for the coveted second ascent of Pinnacle Gulley with Alan Willcox, then considered one of the hardest ice climbs in the East (footnote).

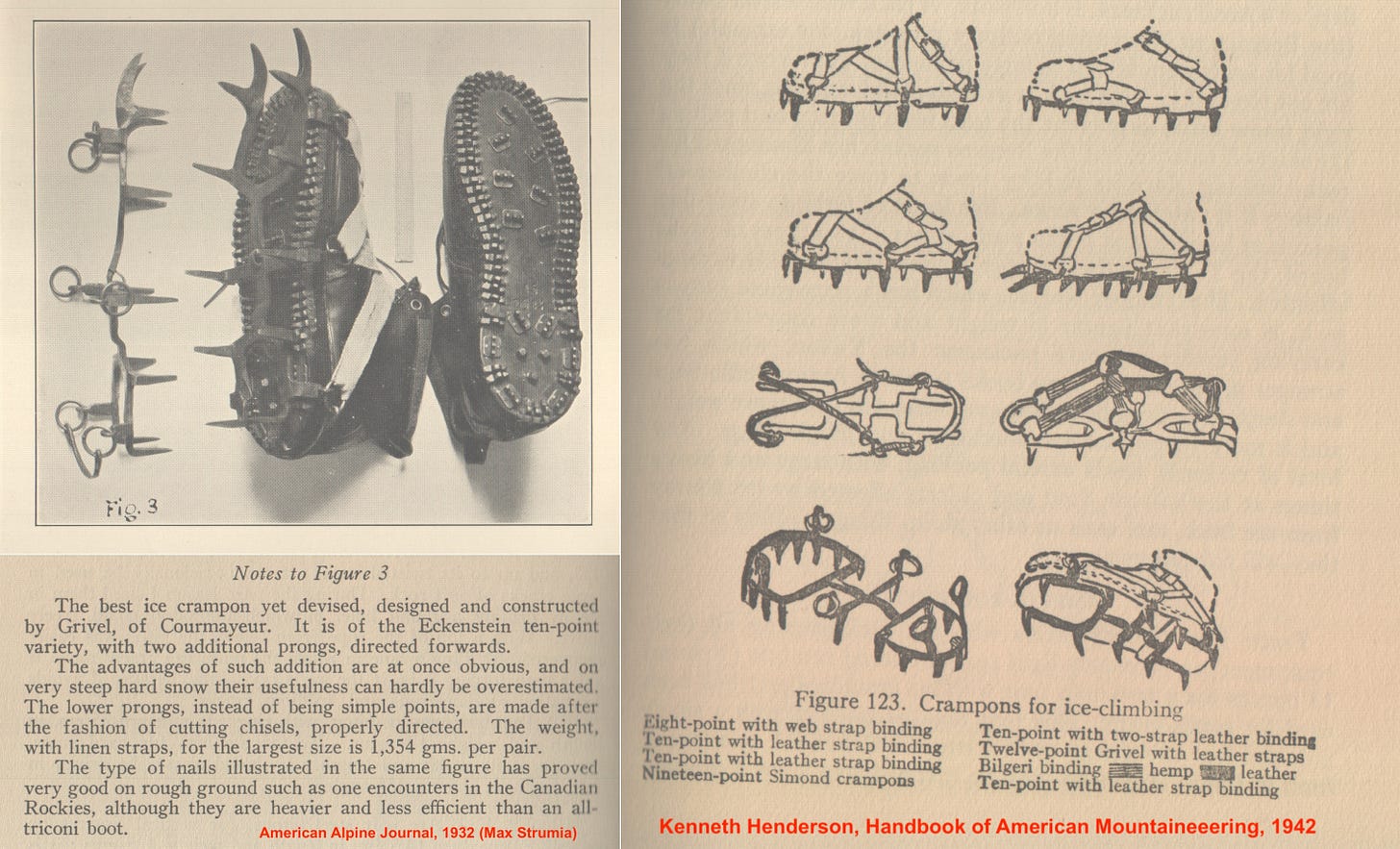

Footnote: On Pinnacle Gulley, House and Willcox chopped the initial steps in the ice one day and completed the route the next. The first ascent four years prior, by two novice climbers from Yale in 1930 (mentored by Willcox), required 5.5 hours of step-cutting and was considered ‘beginners luck’ by the more experienced climbers. As an interesting delay in technology acceptance, even though front-point crampons had been developed in Europe, well into the 1940s East Coast climbers chopped steps (rather than front-point) to ascend steep ice climbs. The availability or reliability of the early models might have been factors. In 1978, Thom Engelbach and I soloed the route with front-point crampons in about an hour or so (see winter pics of Pinnacle Gulley earlier in this volume).

In July 1934, House traveled to Colorado with Betty Woolsey (1908-1997), another top East Coast rock climber (and future captain of America’s first women’s Olympic ski team), and climbed a new route on Jagged Mountain in the San Juan Needles, a technical cutting-edge alpine rock climb. In this developing age of American piton-protected climbing, in 1933 Woolsey and Willcox also climbed difficult technical rock routes in the Wyoming Bighorns. In 1935, House, Woolsey, and Willcox began planning a trip to Canada’s Coast Range, and in May 1936, the elder Fritz Wiessner, who had climbed with the young talent on Connecticut’s traprock cliffs, joined the crew and they soon set out for the great ‘unsolved problem’ of the decade, the mountain of mystery, representing the American Alpine Club (AAC).

1936 Ascent of Mount Waddington

The AAC team planned for six weeks, with 700 pounds (320kg.) of equipment, including a (relatively) lightweight rack of 18 pitons, 8 carabiners, two piton hammers, a 35-meter-long lead rope (noted as a “supple” German rope), a 90-meter-long 8mm diameter rappel line, two pairs of ten-point crampons, ice axes, nailed boots, and Wiessner’s rope-soled Kletterschuhe (protection from falling ice and rock comprised of handkerchiefs and scarves stuffed in their caps). Perhaps with better seasonal weather intuition (footnote), they began their approach from Knight Inlet on July 3, and by July 19, had established an advanced camp at 10,700’ on the upper basin of the Dais Glacier (above the icefall and directly below the SW face). As they were setting up their advanced camp the Sierra Club/BCMC expedition—three teams of three climbers each—were at the end of their attempts at two different routes on the south face, thwarted by weather and difficulties of their chosen lines. Some of the potential lines had been eliminated as options, but a feasible route up Mystery Mountain had yet to be discovered.

Footnote by Don Serl on the 1936 season and Sierra Club/BCMC attempts: “I reckon it can be summed up in two words: "too early". The old timers ALWAYS went into the Coast Mountains too early. The weather in June and early July is (and was) very unsettled, actually with fewer hours of sunshine in Vancouver in June than In May, despite longer days. Plus the temps are higher in June and early July, so the snow (which continues to accumulate in poor weather) is busy falling off everything steep, and turning into deep slop on lower angled surfaces. Early July is perhaps the WORST time in the entire year to be climbing the high peaks in the Waddington Range, but the early parties did it again and again. The SCB group threw themselves into this cauldron of despair in early July. That some of them scraped up the NW summit was a 'just barely' moment, as demonstrated by the failure of the other half of the party the following morning. The weather ALWAYS gets better in the Coast Mtns around July 15 – 20. Witness: Weissner-House: July 21, 1936. Followed by: Beckey brothers: August 6, 1942. Conditions dictate success or failure. And weather dictates conditions.”

It was decided House and Wiessner would reconnoiter the main couloir between the two summits the next day, while Woolsey and Willcox “generously offered their assistance in establishing and supplying our high camp” for future attempts (Wiessner, AJ 1937). Their first nine-hour foray proved fruitless, as the last few hundred feet to the summit was steep rock “impossibly sheathed with ice.” Woolsey and Willcox ‘had not thought they would climb (the next morning), so had not reached the high camp until well into the morning” (House, AAJ 1937). On July 21, at 2:45am, House and Wiessner began climbing the more dangerous right-hand couloir, finding a left branch, “unimposing at first glance, but cutting up high into the upper part of the face.” It turned out to be the key to the route, and by 7am they had escaped the danger of the gulley and made it to the central triangular snowpatch, with 300m of buttressed rock rising above to the summit.

With expert route finding, free climbing at the highest standard, and favorable weather, Wiessner led most of the steep rock climbing on the upper part of the route, while House followed with a heavy pack, and after 13 hours of technical climbing, the pair arrived Mystery Mountain’s elusive summit, a narrow corniced ridge of snow with only room for one. The descent took another 10 hours, requiring all their skill, pitons, and slings, proving to be the most dangerous part of the climb, at one point narrowly missing “whirring and crashing” rockfall. Within 24 hours of leaving their high camp, they returned, heartily greeted by Woolsey and Willcox with hot drinks in hand. Woolsey and Willcox’s disappointment “at their not being in on the final climb was somewhat mitigated by the realization that two was probably the maximum advisable on our route—more than two would have been much slower and infinitely more dangerous.” (House, AAJ 1937).

Fair means evolves

In the British Alpine Journal, Wiessner summarises the technical achievement, justifying the use of pitons for ascent and for roping down (as some still considered fair means depended on downclimbing rather than rappelling):

“Artificial means of overcoming the technical difficulties were not required during the ascent; pitons were used only to secure good belays on platforms and on four occasions between stances so as to give the leader a safer belay over the most difficult parts. Of course the climb could be made without the use of pitons should the party object to their use as a matter of principle, but I feel that this would reduce the margin of safety to an unjustifiable degree. As for roping down, this might be eliminated should the party be opposed to such procedure and if it be strong enough and can spend the additional time.”

Mystery Mountain once seemed impossible, yet a strong team with broad experience and a commitment to fast and light proved otherwise. The ascent marks a significant milestone in North American climbing, perhaps a key turning point in the ongoing debate between pure traditional alpine climbing (without pitons) and the more technical tools and techniques imported from Eastern Europe. Wiessner and House's impressive achievement, climbing the mountain all free in a day with 18 pitons and calculated risks, bridged a divide between the two camps and inspired climbers around the world. The success on Mount Waddington demonstrated the importance of appropriate tool use and helped refine ideal strategies for alpine wall climbing, paving the way for future generations of climbers to push the boundaries of what was possible.

Appendix: Bill House Pitons

In an interview with Dougald MacDonald published in Climbing in 1984, Bill House remembered having his own pitons made: “We had pitons. We had to have them made at a blacksmith, but we knew what they looked like and could tell him.” In the 1930s, European climbing technique books were circulating with images of pitons, and climbers who had visited the Eastern Alps would have been familiar with similar vertical and horizontal piton designs. The two Bill House pitons below have a very large eye compared to modern pitons and would have accepted thick rope rings as a way to attach to the running belay (in lieu of a carabiner).

Jack Tackle Mount Waddington Piton

Jack writes, “In 1977, we climbed a lot of the same terrain as Wiessner and House, I would say that they did have a fair amount of wet rock above the triangular snow patch- which is still 1200 ft below the summit- it has another smaller snow feature above it. What Ken and I did as a new major variation was 5.9 rock and WI4 climbing to get to the upper snow patch-House and Wiessner had gone out left on the much easier ground- but above that last snow patch is where our route crossed and I found this piton maybe 3-4 pitches below the summit on solid 5.8 climbing.”

Don Serl Mount Waddington Piton

Don writes, “I retrieved this piton from the SW face of Waddington, that during the attempt by Joe Bajan and I to climb the route in the winter. I now see that the initials are a stylized 'PH', for Penrose House! This too is a Bill House piton, from the first ascent.”

Dougald MacDonald’s Bill House piton

‘Unbent’ Piton found by author on Shiprock (story to come):

More Notes, stuff to come:

In the Alpine Journal report on Mount Waddington, Wiessner offered advice for future aspirants: “From what I saw of the mountain, I believe that our route is the best and safest way of attaining the summit. However, there are other distinct possibilities. For example, one might find an easier line over the final rocks by going somewhat to the right, S.E., of our route providing traverses can be made round several great overhangs.” These tips were appreciated on the second ascent by Helmy and Fred Beckey ascent (at age 16 and 19), and will segue into Beckey’s 1946 ascent of Devil’s Thumb.

The strong House/Wiessner team’s first ‘rock climbing’ ascent of Devil’s Tower in 1937, followed by Jack Durrance (Dartmouth Mountaineering Club founder) 1938 Devil’s Tower route; Durrance also pushed multi-day alpine rock wall standards in the Tetons.

Bill House was also involved with gear production, helping design and test some of the first aluminum carabiners for the U.S. Army in 1941, and was instrumental in the design and manufacture of the first nylon ropes. After WW2, House chaired the AAC Safety Committee and was the lead signatory on “The Need for a National Mountaineering Safety Program,” which began the AAC’s annual Accidents in North American Mountaineering journal in 1948. These stories and more will be related in future posts.

(photo credits for this research work TK).

Fascinating and fun, John! My father Bill (1935-2017) always wanted to climb Waddington but never did an expedition to do so. Through the Berkeley Sierra Club Rock Climbing Section he knew Dick Leonard, among others from that area and the Valley. I wish I had helped him pursue his Waddington dream -- or maybe he lived longer not going on such trips!