on Skunkworks...

musings of the old days by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Sometimes I get a sort of vivid flashback while taking a long warm shower of Tasmanian rainwater that we collect from our roofs. This one was a flashback of walking around skunkworks.

Sometimes I post things on some sub-forums specific to big wall climbing and recently have been encouraging small makers to take up producing new generation portaledges. The big companies have not updated their portaledge products for over 20 years, and I started thinking about my current shop, and then other “skunkworks” I’ve helped set up, and then about a TV show we filmed the in North Face A5 skunkworks (small “s” not official).

In January, 1997, I transferred my A5 design/production shop to the North Face, the major outfitter for serious expeditions since the 1970s. The TNF athletes climbing big walls were requesting my A5 portaledges with TNF logos, so I figured, why doesn’t the company just buy my S-Corp and set me up with a better shop? That way they could get their ledges for free. That happened, and for a year and a half, a small team of us were collaboratively making a bunch of cool stuff for big wall alpine climbers in San Leandro, as well the challenging task of organizing super-high quality portaledge and haulbag production in-state.

By then I was part of the sponsored athlete team too, with a decent stipend, but I mostly liked the bi-annual free catered trips to climbing areas to hang out with a bunch of my friends and to get gear feedback on all the adventures. The TNF store opening slide shows were a bit of teeth-pulling for me, as I was mostly rehashing stuff from the 80s to early 90s (and my history slide show kinda flopped at the Taos Film Festival). I was mostly focused on design work at the time and had pretty much faded from the active big wall scene (it was the Stone Monkey era—Dean Potter blowing everyone’s mind with unimaginable feats), so the product development gatherings were a cool way to catch up with climbing friends—Alex Lowe, Jay Smith and Kitty Calhoun, Lisa Gnade, Bridwell, Conrad. I could usually still keep up with everyone on the days out on the crags, and even got in front of the lens once on the so-called “A5 pitch” on El Cap’s Excaliber route (A2 with beaks).

There was a lot of theory work involved with the idea of perfecting gear—one example would be applying my thermodynamics from engineering school to discover optimal venting for tent spaces (at one point, I created a few new tent designs for the acquisition department). Jim Penney had some interesting ideas he was bringing from the bike frame world, and we were thinking about new frame designs. The athletes were visiting frequently with all sorts of suggestions and improvements.

It was a very busy 18 months; I was also organizing and coordinating ways to efficiently process the feedback from the field, from a de-facto product development team in the field. A lot of times the very valuable feedback from the field can get lost as there are lots of other things going on in the design process with momentum, so keeping track and combining feedback to make more efficient products is quite a task in itself. It was a bit more difficult than in the old shop to develop whole new tools, as these were generally design projects similar to what you would find in an Architecture school—designs that required late nights and continual development of making models and prototypes, and generally being ruthless with the design process (it didn’t seem to work as well within the corporate walls, parking lot breaks were not the same in the big city). We came up with a few new designs, though—the haulsheath (Jay Smith idea), new haulable alpine pack, waterproof haulbags, a few other smaller things. One thing we did well was to really improve the existing designs. The kevlar Alpine Double portaledge we built for Jay and Kitty was really an optimal light portaledge design for the time made possible by access to improved fabrics and suppliers, all custom built in the shop.

Anyway, back to skunkworks. The term “Skunkworks” was coined at Lockheed in the defense build-up before WWII to come up with new designs and ideas. Wikipedia defines a skunkworks as: “a group within an organization given a high degree of autonomy and unhampered by bureaucracy, with the task of working on advanced or secret projects.” I wasn’t too big on the secrecy, but the advanced aspect really turned me on.

Another thread of that time was that the athletes were bombarded with requests all the time to get out there for some audio-visual exposure. At some point, I agreed to do a film with Mike Graber on canyoneering in Zion. I had mostly avoided getting too involved with the incredible booms of media demand for climbing footage, first with MTV in the late 80s, then with a number of TV shows & movies in the 90s, even though it was happening all around me and orgs like Nat Geo were asking expedition ideas. I liked very much being on the other end, either filming or rigging, and did quite a bit of work in that realm, but the idea of climbing for camera seemed too compromising. I admired Peter Croft in my time in the Valley, doing all the things he was doing in true solitude. Once in 1985 while walking to the Cafe one morning, I bumped into Peter—he had just soloed a few thousand feet in the Cathedrals, was heading up to solo the Sentinel, and planning to finish off the day on Half Dome—over a mile of vertical. You only heard about these things if you ran into him, and as he lived with his girlfriend in one of the Valley dorms, that wasn’t often. But it seemed to me, also, the right way to balance my connection with climbing of the risky sort, and frankly feared a slippery slope of failing to differentiate the two worlds (but hats off to those who do it uncompromisingly well!).

But the canyoneering film project in Zion seemed ideal—back to the place where I still had a home (an old adobe house in Hurricane in a long process of being rehabilitated), and with a sport where I was really only a beginner Zion canyon explorer; it seemed funner (perhaps a more interesting challenge) to do a semi-instructional with concepts I was only recently learning. I recently watched the footage, cringing often, thinking of the multiple takes I needed to get a few lines right, and the serious expression on my face when sifting through the wet sand talking about flash flood. But I really was quite serious about the risk of flash flood, and really feared them. I don’t think Graber really believed me, until a group drowned in Antelope Canyon on a cloudless day, just a week or two after our filming, when an upsteam desert monsoonal cloudburst cut loose a wall of rushing water. Even that relatively small amount of risk to do a film seemed a bit compromising, but it was a fun adventure with Mike to get the shoot done in a week, and for our finale, we descended one of the big ones with locals who knew the canyons and conditions much better (Tim Martin).

I thought about the shoot we did in the skunkworks— I posed with my favourite vest at one point theatrically exiting one of our production ledges and then showed off features of our unique haulpacks design. Posing is the right word—it really wasn’t my cup of tea, but I was doing it for the team, so to speak.

Seems like somehow this all fit into some story…

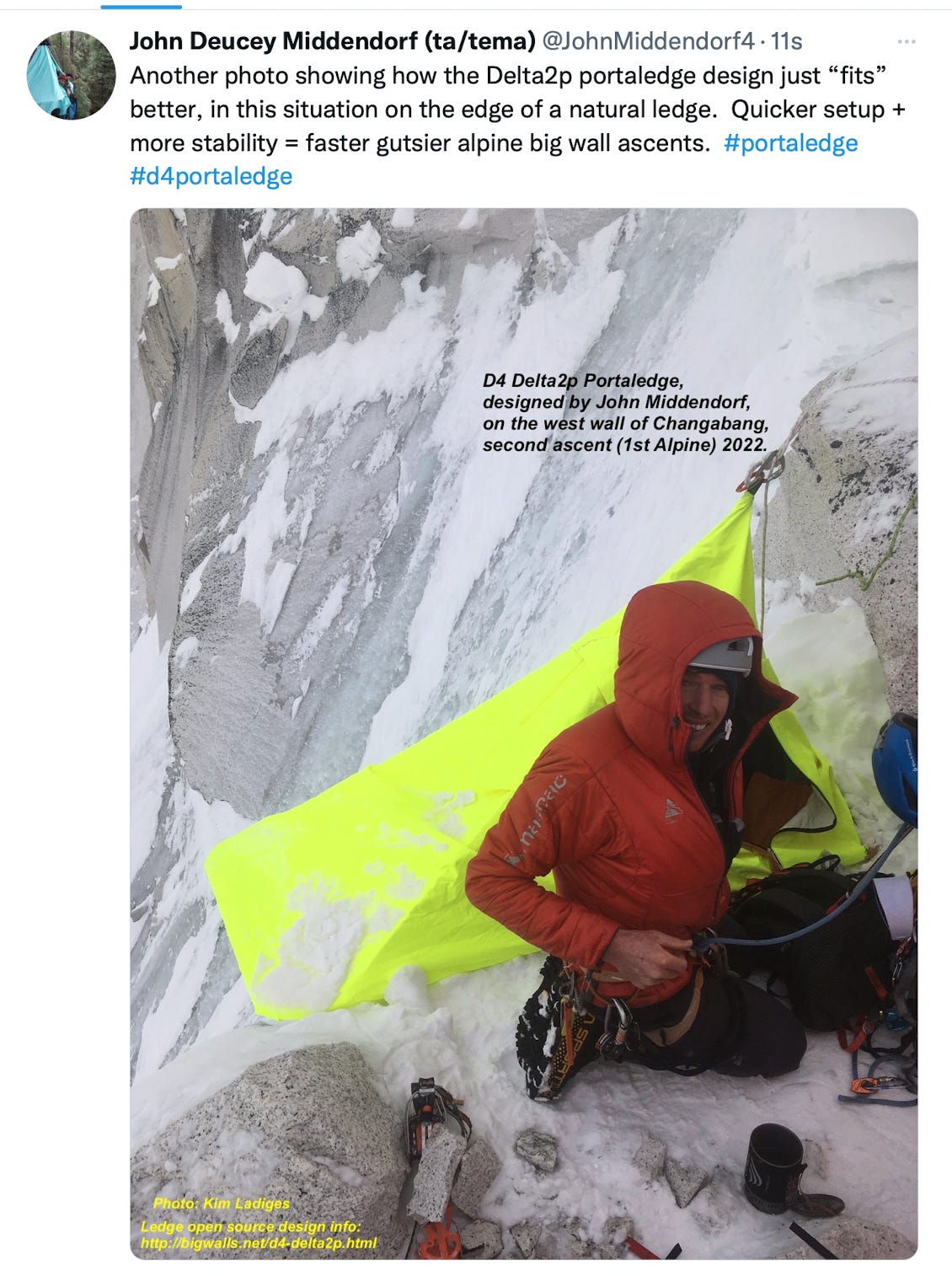

Oh yeah, I was kind of wondering why there are not more skunkworks within the bigger companies these days. Skunkwork collaborations are pretty fun. Maybe they are out there, I do not know. But I suppose this whole train of thought originated with thinking of ways to see my latest portaledge design, Delta2p, made. I made about 40 Delta2p’s in the past years but takes a lot of commitment.

Portaledge Skunkworks, anyone? Open-source portaledge design plans at bigwalls.net. The climbers that have used the Delta2p have said they are the best.

More skunkworks posts: https://t.me/bigwallgear

PS. Now I remember. I was also thinking that for about a dozen years after 1999, I had no shop to build stuff, and was very sad about that (but having tons of fun as a Grand Canyon river guide). But now very happy our house has a big shed—my shop now is pretty much the all the potential skunkworks I can handle these days!

PSS. Actually, we built another skunkworks recently in Hobart at the Bob Brown Foundation, and all sorts of hanging structures are being made there to help preserve Tasmania’s wilderness, and all sorts of creative folk are coming out of the woods (so to speak) to collaborate on projects to assist the brave and tough field protestors who are really the only thing preventing the last of magnificent and unique old-growth rainforests and habitat from being replaced with seeded trees. The table design is really quite simple, and we set up the whole activist skunkworks for a few thousand dollars.

psss. After 2000, I had a few stints in the outdoor industry as a consultant, but with a primary interest in design, I really needed a shop to contribute. On a short stint with BD, it was great to work Tom Jones, who had a pretty nice set up there, but the contract was stuffed by the dot-com financial crash. Had a lot of fun on some overseas business trips with some real pros, below, while working for a internet startup called XDogs, set up by one of my early climbing mentors, Hans Figi.

Psss. Interesting article here.

D4 skunkworks (2017 to 2021):

Hi John, I really enjoyed this trip down memory lane. I hope you get some funding to expand the D4 production process and continue your product development journey. I bought a few A5 tools back in the 90s... wall hammer from Mountain Tools, CA / software from Outside, Hathersage, UK. Still have it. We met once... at a Big Wall Symposium in North Wales around 1999. You were drinking scotch and did not seen very keen to talk to a person wearing a TNF fleece! (Not an employee - a customer!) Best, Michael