Trains and Kain (part 2)

Mechanical Advantage Big Wall series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Summary: focus on Konrad Kain’s early life and use of climbing tools and techniques in the Alps. Previously: Trains and Kain (part 1). These research and story articles are best read on tablets using the Substack app.

Introduction

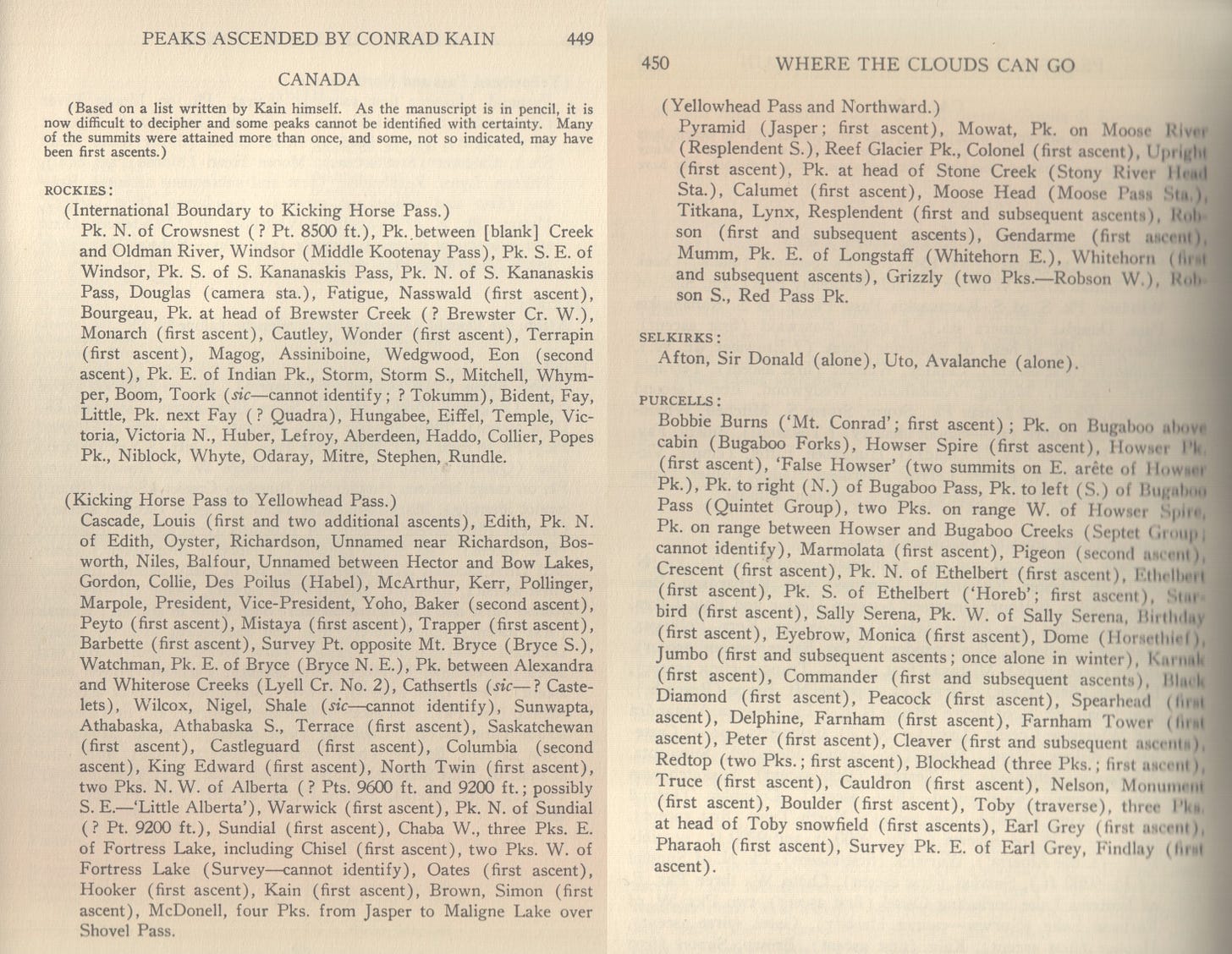

In 1935, J. Monroe Thorington (1894-1989), a prolific historian and editor of the American Alpine Club Journal from 1934 to 1946, published 500 copies of Where the Clouds Can Go, a collection of essays written by the internationally renowned mountain guide Conrad Kain (1883-1934). Kain elegantly captured many of his climbing experiences on paper while he was actively guiding; some he had submitted to periodicals, but most were just filed away or passed to a friend. Thorington had climbed with Kain for six seasons in the Canadian Northwest, and knew him well. After Kain’s death, Thorington was able to collect Kain’s writings from “broken diaries and scraps of paper in a dozen countries of the world,” which he chronologically interspersed with his own articles well researched from Kain’s letters, notes, and other sources, including many personal recollections, to create the classic climbing book, Where the Clouds Can Go (footnote).

Kain’s engaging autobiographical tales and personal letters not only present an amazing climber, but also a great illustration of the professional mountain guiding of the era. Conrad Kain’s history provides a further glimpse of how the steep multi-pitch rock-climbing techniques that originated in the Eastern Alps spread and transferred to the rest of the world, new ideas that are core to how long routes are climbed to this day.

Footnote: A major source of Kain’s life and climbs were over a hundred letters Kain wrote to Amelie Malek, a client whom he had guided in 1906 and became a lifelong penpal and family friend. Thorington used the letters to fill many of the details of Kain’s life and climbs in Where the Clouds Can Go; but after publication, the original letters were lost. In the 2001 Canadian Alpine Journal, Chic Scott wrote that the “greatest Canadian mountain mystery is what happened to Conrad Kain’s letters, journals, and diaries. These are perhaps the greatest single treasure in Canadian mountaineering, and they seemed to have disappeared.” Around the same time, Gerhard Pistor, on a tourist visit to Banff, had seen a picture of Conrad Kain on a tourist visit to Banff and remembered that his father, Dr. Erich Pistor, had told him of Konrad Kain. He visited Don Bourdon at the Whyte Museum, who knew exactly what material might be out there, and Dr. P’s (as Kain wrote of him) archives found their way to the museum in 2005. Pistor had intended to write a book about his former guide and had obtained copies of the letters from Thorington after he had completed Where the Clouds Can Go (the letters had been painstakingly typed up by Amelie after Kain’s death to share with Thorington). These letters are now published in Zac Robinson’s Letters from a Wandering Mountain Guide (2014), an excellently presented and footnoted book. No doubt further insights of this remarkable climber remain to be discovered in the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

Footnote2: In his letters to the Malek sisters (reference below), he used the Konrad spelling until about 1911. When he became a Canadian citizen in 1912, it was Conrad with a “C”. So in this recounting of his story, I will use a K in reference to his adventures to about 1911, and with a C thereafter.

Let’s get to Kain’s story:

Konrad Kain—from Tramp to International Guide

Konrad Kain had a rough start. His father, an Austrian miner, died when Konrad was nine years old; his kind mother destitute. In the early 1900s, Austria-Hungary was in the dying throes of its dual monarchy and was a time of rising nationalism, proxy wars, and harsh economics.

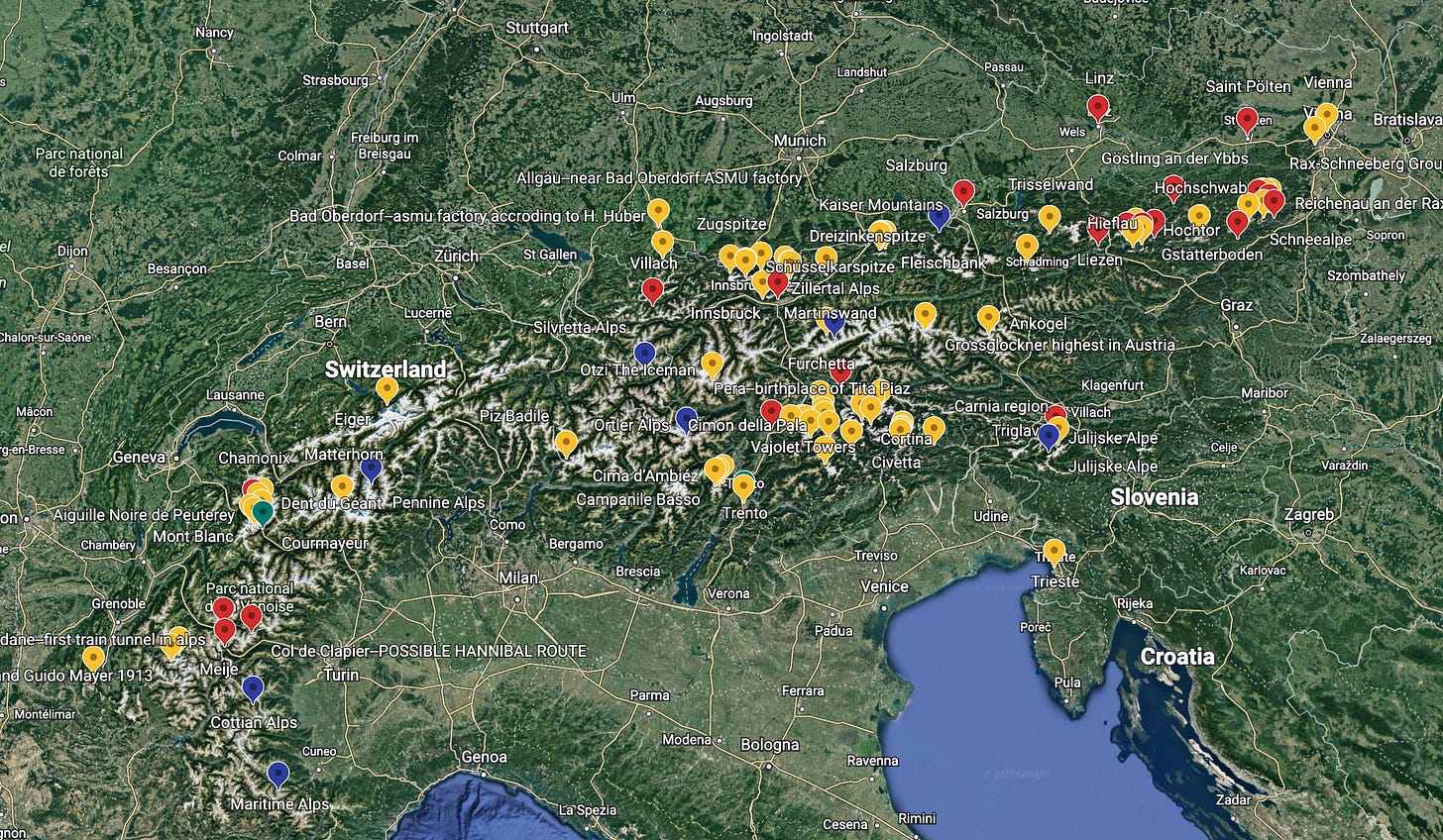

Kain’s home village, Nasswald, is nestled in a valley in Rax mountains, a small but rugged range in the farthest north corner of the European Alps. Just east, the Alps flatten at Vienna and then onto rolling hills until the High Tatras rise. Growing up in the Rax, climbing was a natural way of life; the Alpenstock and decent boots were first child possessions. After finishing school at age 14, he lived in the mountains for a year tending goats, worked as a miner for a while, then left home at age seventeen and “unexpectedly found himself on the road as a tramp.”

Footnote: The mining town Hirschwang, where Kain lived and worked as a quarryman, is just up the valley from Reichenau an der Rax. Mining in Lower Austria and Styria goes back over 3000 years, primarily iron and copper. According to Hauswirth (1989) the mines around Hirschwang had an average iron ore content of 34%, and 4.5kg copper, 201g silver, and 6.3g gold, but smaller remote mines like the ones in the mountains around Hirschwang were mostly becoming un-economical by Kain’s time.

In his writings, Kain recounts rambling on foot around economically depressed Austria as a teenager, finding only sporadic work, stealing bread to survive, and evading police. Vagrancy was illegal and Kain spent time in state work camps, doing hard labor in exchange for a temporary respite from the law, and bare rations. He was tough; with badly blistered feet, no socks, and worn-out boots, for three days Kain hobbled miles and miles on frozen roads seeking medical help, unable to work, and relying on the kindness of strangers and quick wit. Finally, hat in hand, Kain returned home broke and wounded both physically and mentally—“the whole village knew that I had been a tramp. Oh, how dreadful!”, Kain laments. But the experience did not diminish his wanderlust.

A Mountain Guide Evolves from a Poacher (1903-1907)

Helping care for his mother and five siblings in Nasswald, Kain worked as a quarryman in the nearby mining town of Hirschwang until he was twenty-one. Wages were meagre, and he tried poaching for chamois in the Rax Alps to help make ends meet. Chamois (Gämse in German) were quite valuable for their skin and tufts, but hunting them was not only illegal but also quite dangerous. “It is impossible to go through a single day of real chamois-hunting without passing many hundred places in which one false step would be inevitable destruction,” a hunter wrote in 1830. But a tuft of fur from a buck’s back was worth as much as Kain could make in two months of mining; the “Gamsbart”—the long black hairs of the male chamois were coveted decorations for the traditional felt hats of the region (“the bigger the Gamsbart, the greater the status”).

Once plentiful, Chamois had been hunted to near-extinction in many Alp ranges and were protected by gamekeepers in Kain's time. Part of the mountain-goat family, the hooved chamois are quick to evade hunters by out-climbing predators on the steep cliffs of their habitat. Kain recounts stories of rock climbing and scrambling in the canyons around the Höllenthal (“Hell Valley”) in winter, chasing chamois on his free Sundays, twice involving near-death experiences and the eventual loss of his catch through various mishaps (footnote), all while traversing up and down treacherously icy cliffs. On his final attempt, descending at night, Kain fell off a cliff and then tumbled down a steep slope for some distance, “wordless with terror.” Seriously injured, he crawled and hopped for hours in the dark to a tavern. Poaching was illegal, and he was grateful that the hospital in Reichenau recorded it as an “accident on the street” for his discharge certificate, thanks to a sympathetic doctor. Another close call for Kain’s life and freedom but a good example: “Good judgment comes from experience, but experience comes from poor judgment”. Though an unsuccessful poacher, Kain gained a taste for adventure and yearned for more “wanderings in the woods and rocks”. In early 1904 he sold his gun and instead devoted himself to alpine sport for his quarrying days off, and soon became an accomplished alpine skier.

Footnote: It is unclear what happened to the Gamsbart from the last buck he shot, he reports skinning the buck, but then losing it in the fall at night. Kain later references searching and finding fallen bucks on his climbs, skinning and selling their valuable “beards”.

Guiding in the Rax Alps

In his home area, Kain was a pupil of the decorated guide Daniel Innthaler (footnote), who was noted in the 1902 German-Austrian Alpine Club (DuÖAV) journal as the “only suitable guide for really difficult tours” in the Rax mountains. Once the sole domain of goat herders and traveling tramps (the Archbishop of Vienna once said he could not conceive of "a lonelier and more horrible …wilderness”), by 1905, over 15,000 people were coming to the Raxalpe for recreation, mostly from Vienna to climb established routes (DuÖAV). As elsewhere in the Alps, more and more mountain routes were becoming equipped with “security”: ladders and anchored wire cables for the “high tourists”, but there was also increased demand for roped climbing with local guides on the more technical climbs—there were fifteen routes of various difficulty in the Rax at the time. Kain was well poised for this boom, and began his guiding career on his 1904 Easter holiday, by meeting tourists as they arrived in town, and inviting them up climbs. His first two days of guiding work earned him two weeks’ quarrying wages. “I went every free day to the Höllenthal in order to learn all the climbing routes,” after that, he writes.

Footnotes: Daniel Innthaler of Nasswald (1847-1925) climbed many of the hardest routes in the late 1800s and was awarded the Cross of Merit in 1903 at the Reichenau Alpine Rescue Station for his zeal and dedication on rescue efforts in the Rax and Dachstein Alps. He continued guiding to an old age. Although Kain only writes of a few encounters with Innthaler (but noting that he was his pupil), Thorington notes that Innthaler was Kain’s ‘teacher’. Kain once wrote chapters of a story with Innthaler as a character (referenced in Letters, 1933) but it has been lost.

Regarding the fifteen routes on the Rax at the time, history on the old routes is patchy (current guide here) but Kain writes about a few: the Katzenkopf, Akademik, Quartette, and the Karl Berger route. Routes can be as long as 800m in this Northern Limestone Alp range. Kain climbed a difficult variation to the Weiner Neustädter Steig in the Rax. Karl Berger had first ascended some of the hardest technical rock climbing spires in the Tyrol and Dolomites; he is most famous as one of the first ascentsionists of the technical rock climbing breakthrough Campanile Basso in 1899. In the appendix, there is a postcard of Karl Berger on a steep rock climb possibly in the Rax Alps. Berger, like the great climber Hans Dülfer, was killed in WWI.

A boom in guideless climbing was also happening in the Viennese Alps, prompted by the Naturfreunde (Nature Friends) movement, an environmental organisation started in 1895 in Vienna, with thousands of members, who sought to share their love of mountain recreation and to provide rescue services. Kain writes of his friend and Naturfreunde member Franz Hahn, who fell and died on a climb in the Rax: “Only those, who like poor Hahn, buried today, laying out his own hard-earned kreuzers for nature, and finding his joy in the mountains; only those can be called nature friends” (Kain was very cognizant of social/wealth divisions). From 1890, the Gebirgsfreund, (Mountain Friend) was a monthly from the Austrian Mountain Club based in Vienna with Mizzi Langer advertisements and Gustav Jahn illustrations; in its first issue, the editorial encourages alpine excursion in more distant ranges like the Ennsthal high mountains (~150km east of Vienna), which were “touristically” connected to Vienna via the “pleasure train of the Austrian State”. Innovation was happening in Vienna.

Four Tenets of Guiding

Learning from early epics with rockfall, dropped equipment, unplanned bivouacs, and wild weather, Kain polished his craft and soon became a sought-after guide, as well as a rock-climbing prodigy. Later Kain was to describe four points of confident guiding:

Never show fear.

Be courteous, and always pay special attention to the weakest in the party.

Be witty, and be able to tell convincing white lies at the spur of the moment.

Know when to show authority, and when the situation demands, to give a good scolding to those who deserve it.

Indeed, within a few years, he developed the qualities of an invincible outdoor guide through hard work, grit, “go-for-it”, and learning from his epics. Kain felt these tenets critical to hold the confidence of any party, and helped him gain devoted clients and create partnerships on legendary mountain climbs all over the world.

Footnote: On my first time down the Grand Canyon rowing an 18’ raft for two weeks with clients, my friend and mentor Roger Dale provided me with nearly the exact timely advice, learned from experience as a professional.

Kain’s Clients and Mountain Climbs

In 1904, the wealthiest Viennese mountaineering “amateurs” were touring by automobile to alpine towns on new motor roads; patrons would contract local guides on planned trips to distant mountains. Guides would travel via train and foot, sleeping in guides’ huts and or hotel stables, then meet their clients at resort hotels for the day’s climb. Kain’s guiding work in the European Alps was seasonal and remained a sideline to his quarrying job (when he could negotiate time off), but Kain was soon contracting guiding work all over the Northern Limestone Alps.

Kain writes of many clients only by initials: Mr. H, “one of the wealthiest in all Vienna” was a real stinker, shafting Kain on his wages and refusing to pay for his return travel, abandoning Kain far from home. He once got benighted on the Pfannl route on the Oedstein with Dr. B. who feared death and became irrational during a long cold unplanned night perched on a ledge (Kain responded with tenet #4 above). He climbed a lot with Dr. B over the years, a very difficult client who often wanted to climb something too hard for him, then blamed Konrad if they didn’t make it (once Kain had to haul Dr. B “almost two meters through the air!” on the Schmitt chimney on the Fünffingerspitze). But with each epic, his experience on how to safely handle situations in the vertical environment grew. He also developed an eye for a line, both for the approaches and for the often complex route-finding on the steep rock walls of the Alps. If he couldn’t find a client, he climbed solo, taking rest days only for storms or injury (footnote).

footnote: On days his clients were late or needed a rest day, Kain would be on the lookout for work found on the spot. On his first trip to the Ennsthal Alps (various spellings), seeing a team of two men and a woman who looked like climbers, offering to carry “the lady’s rucksack” and following them up to the base of a wall. Then, in conversation about their ropework and their experience, further offered to lead the team up the route on the Hochtor. The climb was much harder than the team had imagined and were grateful for Kain’s help and ropework. He was tipped twenty Kronen, about 10-days mining wages; it was the most money he had ever made in a day. Generally, he would try to solo each route prior to taking clients, but that was not always possible and led to some epics of route-finding and getting benighted (back in my day, spending an unplanned cold night half way up some climb was a rite of passage—on cliffs like Cathedral Ledges, Cannon, and even the Gunks (going for that one last climb and taking longer than expected), if you were not getting benighted every once in a while, you were not really going for it).

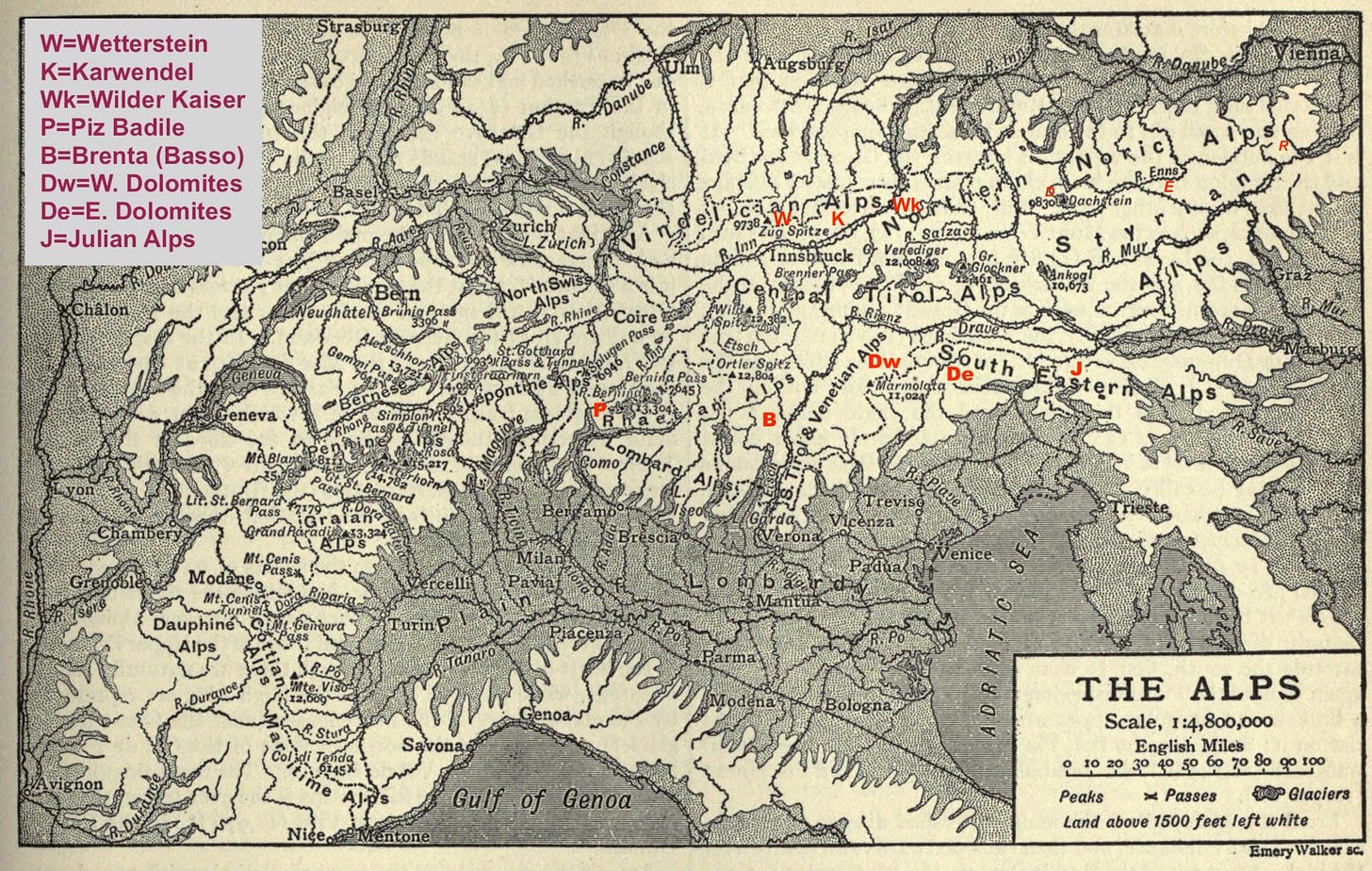

One client, Dr. P (Dr. Erich Pistor, introduced in the last chapter) became Kain’s prime guiding benefactor and with his wife Sara, both good climbers, toured all over Europe with Kain. Within a year of chopping his first step with an ice axe on an icy approach slope, Kain was guiding the most famous and feared peaks all over the Alps: the Matterhorn, Monte Rosa, Mont Blanc, Meije, Weisshorn, Barre les Ecrins, des Grands Charmoz, and dozens of others in the years following. He was also meeting many of the established Alps guides whilst traveling through all the cool mountain towns: Chamonix, Courmayeur, Zermatt, Interlaken, and others, and gaining a reputation of his own.

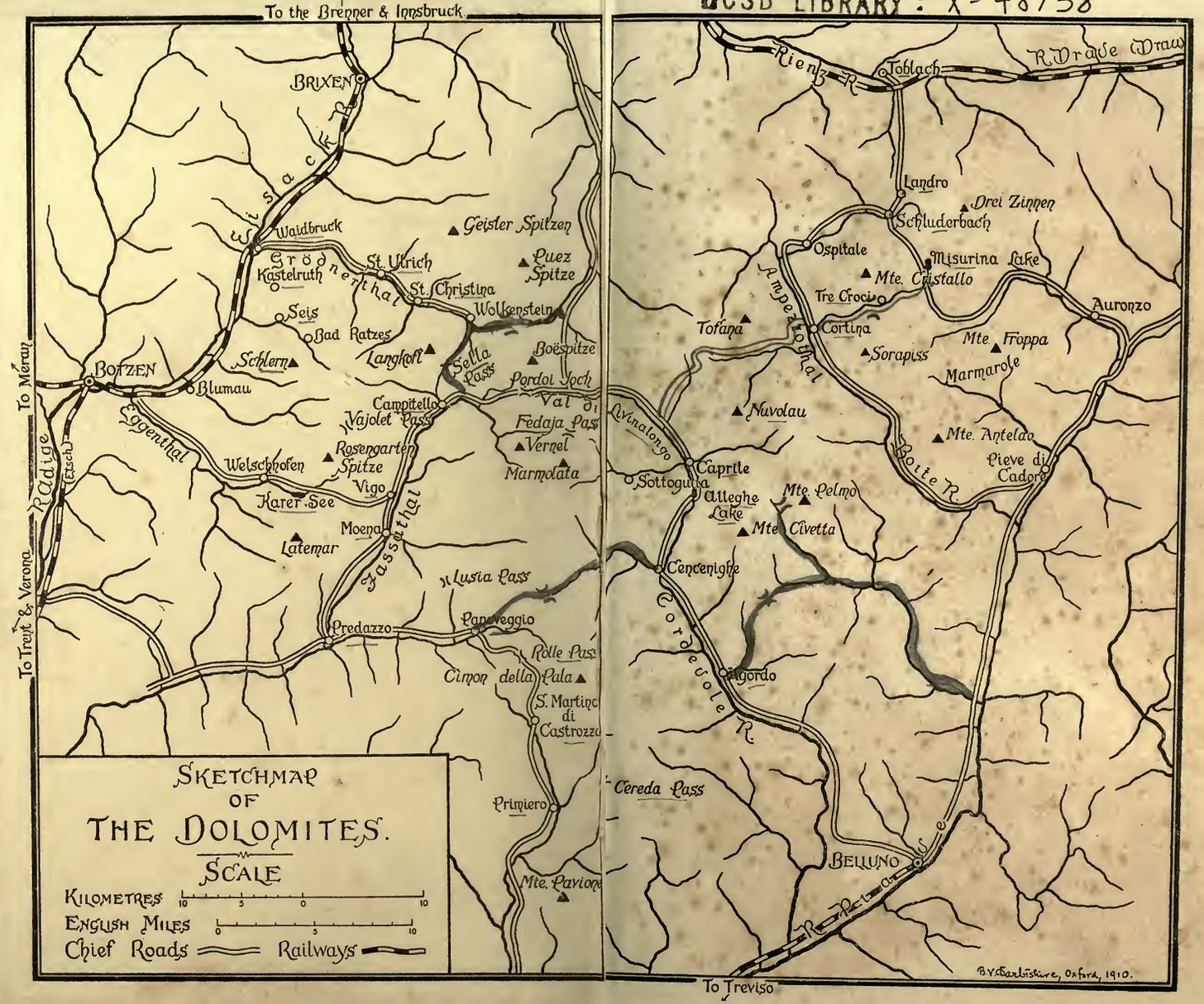

Not only was Kain learning the art of safe alpine mountaineering, but was also becoming an expert rock climber and capable of efficiently guiding clients on the hardest technical rock climbs. As was the case with his later guiding in Canada and New Zealand, his primary business was guiding the highest and most famous peaks, but Kain writes most intensely about his steep rock days on the limestone walls and dolomite towers. He soon became a top-tier technical Eastern Alps rock climber, approaching the abilities of specialist rock guides like Tita Piaz from Pera, Franz Schoffenegger and Franz Wenter from Tiers (who often recommended each other when clients were looking for steep rock objectives in the others’ areas). Let’s consider a few of the climbs of Kain’s experience.

footnote: Kain got into a few fights with local guides, as an ‘out-of-towner’, but he also made good friends with many guides who were helpful in tips and information, (i.e. Schroffenegger, Wenter, Steiner, Müller, Zettlemaier, Schneeberger, Kaindl, Innerkofler, his “teacher” Innthaler, Piaz), as well as other luminaries who offered good advice, e.g. the eminent painter and illustrator Gustav Jahn and Franz Kauba, husband of the famous ski racer and outdoor shop owner Mizzi Langer (where Kain purchased his climbing gear and pitons). He was also noted by the highly regarded Vienna climbers Vineta and Alfred Mayer, whose two sons, Guido and Max, would soon be climbing the longest and hardest big wall routes in the Dolomites in the 1910s.

Onsight solo of the north wall of Hoctor in 6 hours (1904)

With only a few months of formal rock climbing experience under this belt, in the summer of 1904 Kain free soloed the north wall of the Hochtor, considered by the Tyrol climbers as one of the most difficult Eastern Alps ‘tours’. The 1905 DuÖAV journal noted that Kain climbed it “in six hours from Gstatterboden!” (a rare exclamation point from the editors). Kain wrote, “One can only do it this quickly if one is alone. With one of two persons in addition there can be no fast going.” Kain reports finding his way by following fixed pitons. He sometimes trailed a rope and “roped up” his rucksack on steeper sections. En route, he came to the “Flying Ledge” where there were several pitons used for upward progress, but Kain said, “that did not seem so difficult for me.”

Fast climbs on the Zgimondyspitze and the Dachstein

Back then as now, there were classic routes of repute that were rites of passage. One of the very first long modern granite rock climbs (1879) was the Zgimondyspitze, a centerpiece of the Zitterthal Alps and in 1904, a testpiece for multi-pitch rock climbers. Kain with Sara and Erich Pistor (Dr. P) climbed the route in an astonishing 32 minutes. Leading talented clients on technical ascents like these were more partnerships than the typical high-altitude (4000m) mountain tours, where tedious step-cutting up ice and snow was the guide’s most arduous task.

On the south wall of the Dachstein in 1905, which Kain climbed with his friend “R.” (a “keen scrambler from the Rax”), they were an efficient team and climbed the El Capitan size wall (~1000m) in 3.5 hours, almost certainly a record at the time. A month later he led the same route with a client (Mr. St.) in 10 hours. Only a small percentage of alpine guides were at this level of guiding involving endurance, quick thinking, and careful route-finding and anchoring skills on these big walls of rock.

Footnote: In 1936, the British alpinist L.S. Amery wrote after climbing the south wall of Dachstein with a partner in nine hours and placing a few pitons, wrote, “My experiences of these limestone climbs in the last few years have, I may say, entirely converted me to the view that, used in moderation, the piton or ring-topped peg driven into a crack in the rock and the Karabiner or snap-ring by which the rope is attached to it, are perfectly legitimate mountaineering devices, adding greatly to safety as well as calling for their own technique.” Climbers in the British Empire were about thirty years behind the climbers in the Eastern Alps to accept their legitimacy.

“All-Alone” Guiding

In the 1904 and 1905 fall seasons, Kain was gaining experience on the long steep routes of the Dolomites and the Tyrol, multi-pitch climbs with secure anchors for belays. Kain started guiding in an era when two guides per team were considered a minimum for challenging climbs, but Kain was often guiding two patrons by himself even on the steepest and most complex routes. Talented guides like Tita Piaz were further developing a single guide technique on mostly vertical multi-pitch routes, with the ability to secure clients at belays, eliminating the need for a second guide to safeguard clients. It took another two decades for these techniques to begin to filter to the rest of the world as the optimal team system.

On his first trip to the Dolomites, he guided Sara and Erich Pistor (Dr. P) up the Gross Fermeda Tower, first climbed in 1887 involving steep slabs, overhangs, and an icy ridge to finish. Kain writes, “That evening a fight occurred between myself and a guide from Taufers. He said to me: "‘What, you are going all alone with both these people on the Gross Fermeda? Even the best local guides don’t do such a thing. Then everyone crowded me and threatened me with blows. In spite of it I could not be quieted for a while, and the quarrel lasted for some time.” He admits later that he took some risks on the snowy ridge, but had no issues keeping his team moving quickly and safely on the vertical walls.

Eastern Alps Rock Climbing Technique with Schroffenegger

After meeting the Tiers guide Franz Schroffenegger on Grasleiten Tower, they guided together with their clients on Vajolet Towers, where Kain learned new single-guide belay techniques. On the Torre Delago, which at the time Kain considered “a tour on the border of human possibilities,” Franz taught him the “mealsack technic,” the advancing art of organizing “security” (a belay), then holding, raising, and lowering a client on hard steep routes. Kain writes: “Once I read in the paper: ‘Meal-sack technic on the Delago Tower.’ A man described how he had been handled in this fashion. He was an honest fellow to tell everything truly which most Delago climbers hide.” (footnote).

footnote: Clients were generally lowered from the rock towers, then the guide descended using a doubled rope using the around-the-leg & foot-brake abseil technique. Franz Schroffenegger from Tiers, one of Tita Piaz’s partners on the west wall of Totenkirchl, was one of a handful of guides doing the hardest steep rock climbs, often first establishing pre-placed anchors at belays. In his book, Kain refers to Schroffenegger as Hans and Johann. Later, Kain guided many of the hardest routes on the Vajolet Towers and other testpiece Dolomite towers.

Equipment

Kain did his early rock climbing in wool socks rather than his heavy mountain boots, but soon acquired a pair of the new tight-fitting ‘Kletterschuhe’ for his rock climbing. The canvas climbing shoes with braided hemp rope soles were starting to be popular in the Eastern Alps and considered essential for real rock climbing. On the Grépon in 1905, Kain writes of pulling a Chamonix guide struggling up the Mummery Crack: “He had nailed boots, for the Chamonix guides do not understand Kletterschuhe and are not willing to try them. ‘He kept calling: Hold tight! Hold tight!’” On trips to new areas, hiring a second, local guide was considered obligatory, but Kain found it much easier on hard rock climbs to guide on his own, especially if he had to employ the mealsack technic for the mountain guide (footnote).

footnote: Word quickly got out on Kain’s ability to seamlessly guide steep routes, and other clients, many good rock climbers, sought to hire Kain to lead routes as their only guide; he climbed the Grépon three times while in Chamonix, for example. The French guides threatened, but the respected Swiss guides stood up for him (he was remembered for having “fled from a volley of stones in the streets of Chamonix”). Kain also mentions the Chamonix guide’s “new spikes (which the Swiss guides have instead of climbing irons)” ←for ice tool historians (1907).

Kain and Pitons

Kain only mentions Mauerhaken (pitons) a handful of times in his writing, but it is clear he was both using fixed pitons and placing new ones on many of his climbs. On some first ascents on the granite cliffs of Corsica in 1906, he was equipped with a hammer and pitons: he took the time to show—and perhaps practice—the techniques to some locals: “I showed the herdsmen how to climb on the big granite block (our house), put in a Mauerhaken and roped down. They had never seen anything like that!” Kain writes. Then Kain and Mr. G, “a good rock-climber”, climbed the center peak of the Cinque Frati (Five Monks), then traversed to the two highest towers involving exposed overhangs and rappels. Von Albert Gerngross (Mr. G.) writes in the Austrian Touristen-Zeitung (a bi-weekly newspaper), “We climb the Cinque Frati (2003 m), those five sharp jagged rocks that rise from the Virotal have never been climbed, and we want to climb. We have provided ourselves with Mauerhaken and rope slings and expect a tough tour from this last day in the beautiful Niolo.”

footnote: Quote from Kain letter to the Maleks; the event is included in the history of mountaineering of Corsica is La Corse des Premiers Alpinistes 1852-1972 by Irmtraud Hubatschek and Joël Jenin (2021). Many climbers made their own thin pitons at this time, probably thin blades of steel with a hole for a rope sling; Kain, with no blacksmithing skills, was most likely procuring pitons from Mizzi Langer in Vienna, which were probably the L-shaped “wall hooks” also popular at the time. Franz Kauba (husband and co-owner of the Mizzi Langer’s shop) organized the client for Kain’s Corsica expedition, where they met and bought other equipment for the trip, including ice axes. See the piton chapters and Mizzi Langer pages of this series.

Footnote: Kain and his client Albert Gerngross climbed over eight peaks in Corsica, primarily rock climbs, and at least three first ascents. The French journal La Montagne (June 1911) also reports Kain and Gerngross’s first ascent of the northeast wall of Punta di Castelluccia, with its “superb vertical wall” (the author, André Lejosne, tried but failed on the route in 1910). The others are listed in the appendix below. Photos:1909 Alpine Journal, Austrian Tourist News (Vienna, Oct 16, 1909). Thanks to Stephane Pennequin for the third photo and further details on Corsica climbing.

Kain had gained his official guiding license from the German-Austrian Alpine Club in 1906, which he had applied for in his first year, but by this time he realized he did not need the official recognition to gain clientele, and usually left his Führerbuch (leader logbook) at home; he writes, “I did not like to show that I was a guide.” He was fully booked by word of mouth. In between his big mountain tours, he was arranging back-to-back clients for long rock routes in the Wild Kaiser, Ennstahl Alps, Sella Towers, Dachstein, and other rock climbing areas. And he often climbed harder routes solo. On his way home after a month of guiding high peaks in Switzerland and France in 1906, he stopped by way of the Ennstal and set about rope-soloing a new route on the north wall of the Planspitze, a “Kain route”, he writes. But after reflecting “going alone over such smooth walls is too dangerous, and I had no Mauerhaken”, he retreated.

Campanile Basso/Guglia di Brenta (1907)

By his third year, Kain’s guiding seasons were long and full, and he was traveling throughout the Alps working and climbing. After another summer season in Chamonix and Zermatt, he climbed the Campanile Basso with Dr. L., and like many on this 300m testpiece tower, he found his way on the complex route by following the fixed pitons along the route (theirs was the 42nd ascent), as well as marking papers left by others. At the Garbari Pulpit, a large ledge high up on the route and only a half pitch from the summit, he saw “two iron spikes and a new rope-off ring. Without doubting I was on the proper route I stormed upwards to the overhang. That stopped me! I tried three times. Impossible. Dr. L became impatient as he was getting cold. I told him to rope (me) down, and I anchored myself.” After Kain consulted the guidebook, he followed the original route, the famous bold and blind traverse around to the steep north wall where there were more fixed pitons (including one generally used for upward progress), and writes, “to this day I have never done another bit so exposed” (footnote).

footnote: Little did Kain know, but several years before the guide Nino Povoli from Trenti had climbed the difficult direct variation, finally redeeming himself after having failed on the first ascent attempt of Campanile Basso in 1897, when he was ordered by his client Garbari to climb the headwall without pitons, but refused (see also Campanile Basso di Brenta chapter).

Later Kain was to reflect on the “following climbs as ideal: the Vajolet Towers, the east face of Rosengarten, the Fünffingerspitze by the Schmittkamin, the south face of Marmolata, and the north wall of the Kleine Zinne. I was so infatuated with the Guglia di Brenta that I went many miles out of my way to climb this majestic pinnacle. In the (first) three seasons I spent in the Rockies I had not made a single climb, and did not expect to make one, that could be compared with any of these” (1909-1911). Perhaps like phonically related Citizen Kane, Kain’s “rosebud” was the Guglia di Brenta, perhaps the longest continuously steep rock climbing route of his career. In one of the many times Kain felt deep Heimweh (homesickness) for his homeland when living in Canada, in a 1929 letter home he wrote, “As you expect to go to the Tyrol I will ask you a favour. If you see a picture of Guglia di Brenta, please buy one for me, put it in your suitcase and send it when you get home. Bon Voyage.”

Marmolada (1908)

Kain climbed the 19th ascent of the 600m south wall of Marmolada with Piaz and two clients in 1908. First climbed in 1901 by Beatrice Tomasson and her guides (see Early Piton Evolution 1a), in 1908 the route was still a renowned rock climbing testpiece. Kain only writes a brief, one-page recount of the climb in his diaries, acknowledging accepting a toprope from Piaz on an overhanging block pitch, but in a letter home to the Maleks, he credits the saving of Piaz’s life: “This has been my most difficult tour. Then came another critical moment: the guide, Piaz, and his gentleman started sliding and fell. And we were on one rope! Fortunately, I had a good hold with very good security.” The term “security” in those days meant a secure anchor—a tied-off strong horn of rock, or pitons and rope slings. They climbed the wall in 4.5 hours; “We climbed too quickly. It gave me no pleasure,” Kain writes, “I can only recommend this expedition to those who have already done the most strenuous things in the Dolomites.”

footnote: Kain had a few other close calls. Once, he fell when a grassy ledge collapsed on the Vienna Alpine Club route, Dr. P had a tree for security and belay and caught the fall. In letters, Nov 10 1908 rockfall on Stadelwandgrat. There’s more I will try to add later (rock fall Barre des Écrins in Dauphiné and Meije, also Canada & NZ avalanches provide some insight on Kain’s instincts, judgment and quick thinking).

Trisselwand with Elisabeth Benedikt (1908)

In the Totes Gebirge, the most northern of the Northern Limestone Alps, a beautiful 500m wall of stone rises above the dark blue Altausseer See. The southwest wall of the Trisselwand, situated in a more remote part of the alps, was relatively late among the prominent limestone faces to be first ascended by its easiest route. There were many legends about an inaccessible cave high up on its cliffs, known by geologists as a “Halb-höhle” a karst half-cave that soon ends in collapse but looks from below as if it was a deep passage into the depths of the mountain. Some stories tell of “wild women” living in the cave; others say it is the home of the Krampus, the horned half-demon that torments misbehaving children in winter seasons. Kain references the cave as the Tauben-Ofen (Pigeon Oven).

Footnote: Altaussee is the birthplace of Paul Preuss, born in August 1886 at his family’s summer home, and where he later found the strength to recover from polio in his first decade of life, gradually increasing his range of walking around the lake. These days it is a pram-friendly three-hour hike to circumnavigate the lake. Both Preuss’s and Kain’s fathers had died before they were ten years old, and Preuss’s trip to the Gesäuse to first climb the Austrian testpieces there were only a few years after Kain’s (who was three years older). Through the sisters Elly and Karin Benedikt, who lived in Altaussee, Kain and Preuss might have known each other, but certainly would have known of each other, one from a working-class background, and the other from a well-off family. See Paul Preuss, Lord of the Abyss, by David Smart. Note: I might be wrong about the Tauben-ofen, but I think it is the hole on the wall seen in a photo in the appendix below.

In Alt-Aussee (now Altaussee) lived Elisabeth Benedikt with her sister Karin. Kain first guided Elisabeth in 1905 on the Planspitze, then traveled and met her in Alt-Aussee. Kain writes of Elisabeth, whom he refers to as “Miss B.”: “For several years she had planned a first ascent of the Tauben-Ofen but had never found anyone in Aussee who would go with her.” Kain asked the local authorized guide, who bragged he was “the best of mountain climbers,” but when Kain asked about a direct route up the Trisselwand by way of the hole, the guide got angry and said, “None of us have climbed up there, and you arrive for the first time, understand nothing about it and want to go up? You will roll down right down into the pebbles.” Kain could see the route would not be difficult, and the next day he soloed up and explored the cave, and could see how the route would easily continue. Kain promised to return to climb the route with Elisabeth (footnote).

That same month (June 1905), Hans Reinl had the same idea, and also made some exploratory climbs. The next year on May 13 1906, Reinl with Karl Greenitz and Franz Kleinhans returned to climb the first ascent of the SW wall creating a classic “Reinlweg”. Kain apparently returned to the Trisselwand at the end of June, 1906 to investigate climbing it by way of Trisselwand Pass, which he said, “the people there did not believe it could be ascended from that side”. It appears Kain was on the hunt for a new route on the Trisselwand to do with Miss B.

Over the next three years, Kain climbed with Elisabeth, and occasionally with her sister, on successively more challenging climbs, first in his home area the Rax (April 1906), then the Pichl route on the Planspitze (Oct 1906), an attempt on the Bischofsmütze (Nov 1906, too snowy), climbs in the Ennstal (footnote) and cumulating with an exciting climb of the south wall of the Dachstein (Sept 1907), complete with rockfall—“an avalanche of stone, which for a short time placed us in the utmost danger”—and a swinging fall on the crux of the route—“she swung out nearly a meter and a half, and lost her hat.” Not to be outdone, Elisabeth’s sister Karin sent Kain a telegram to stand by for the same climb. During their ascent, Kain complains of her equipment (her four pairs of boots!) but mentions, “she was a very good climber, only self-centered and of different character than her sister. The lady made the difficult traverse very easily, and I must admit that she never put her whole weight on the rope.”

Footnote: Kain mentions planning to be in Aussee on June 30, 1906, but there is no record of his time there. In September 1907, he met Elisabeth in Aussee and they traveled together to Gstatterboden for routes in the Ennstal Alps. In the Hotel Gesäusse, Kain met three women “two girls with their mother”, whom he had guided up the Hochtor in 1906, with whom he was on friendly terms. Kain implies both jealousy and teasing from Miss B. on that occasion. He also mentions climbing the “Grat” (probably Stadelwandgrat in Rax) with Miss Benedikt in his letters to Amelie Malek.

Finally, in September 1908, Kain met Elisabeth in Altaussee for their long-planned climb of the Trisselwand. They were aware of the 1906 Reinlweg, which by that time had a reputation and been repeated several times. Theirs might have been a separate line, as Kain notes, “the native guides were aware of the lady’s project, they came to me and said we were both fools; it was impossible to surmount such a rock wall. I told them it had already been done by the engineer Reinl. ‘It has not!’, they all shouted together.”

It turns out they followed a route climbed by Paul Preuss alone, only days earlier, who had left Mizzi Langer Markierungsblätter (marking papers), showing the way. Kain also found a fixed rope in a chimney which he “rolled up and tossed down”. A young girl from Alt-Aussee had hiked to the summit, “curious to see whether a woman could really ascend the Trisselwand.” Kain writes, “If we had not had the boy at the start and the girl at the finish of the climb as witnesses, no one in Alt-Aussee would have believed we had done it.”

On September 26, the Steierische (Styrian) Alpen-Post reported the “daring tourist Miss Elisabeth Benedikt from Vienna,” who had dreamed of the climb as a child, climbed the 1000m high (sic) wall in less than five hours with Konrad Kain from Nasswald “without the slightest accident.” But Elisabeth took offense to the published praise, and downplayed her accomplishment as “second in rope.” In a response letter to the Alpen-Post, she writes, “Four days before our ascent, the Durchkletterung (route) was solo climbed in dubious weather and wet rock, namely from Mr. Paul Preuss from Vienna, who has spent the summer months in Altaufsee since his earliest childhood. We also owe our ascent to his marking of the whole route with red paper strips.”

footnote: On October 4, 1911, Preuss climbed the direct west pillar of the Trisselwand with Dr. Gete Loew from Vienna, and the guide Hans Hüdl from Aussee in 8.5 hours. In the December 2, 1911 Alpen-Post, Preuss admits to reluctantly placing two pitons on a tricky and risky traverse, the only pitons he placed in his short but brilliant mostly onsight-solo climbing career (though in his early career, he did sometimes use fixed pitons on rope solo ascents). David Smart found that in 1911 Preuss took the two sisters Elly (Elisabeth) and Karin Benedikt up the Reinlweg separately on the same day. The 1914 Mitteilungen also reports a new route on the West Pillar by Minna Preuss and Rudolf Redlich on July 24, 1912.

Elisabeth was known to be a painter, but very little else is known about her. As rock climbing the steep walls of the Alps developed, more women were entering the sport and soon climbing at top levels, and like many of the men even Preuss, they sometimes climbed with guides to advance their craft (footnote). Like the ten-year “missing history” of Beatrice Tomasson (1901-1911), very little information survives about the women who were big wall climbing in the first decades of the twentieth century.

footnote: Kain and Elisabeth did one more route: the Jahn-Zimmer on the north wall of the Hoctor, which was put up in 1906 and became the more classical route up the north wall of the Hochtor, with 28 pitches of continuous technical rock climbing (see “topo” above). It would have still been a fearsome route in 1908, and Kain reports, “At the difficult traverse I fastened the lady to the Mauerhaken.” He wrote of Miss B., “I was astonished at the endurance of the lady.”

Off to Canada

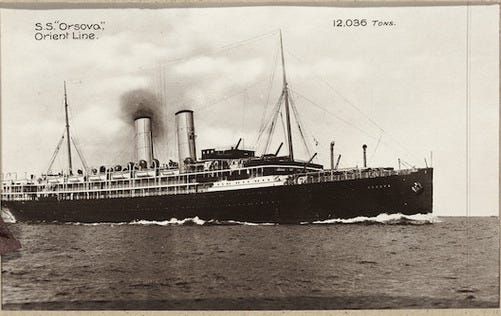

Even though Kain worked every day possible throughout the season, he ended the year with little savings. He writes, “Now the year 1908 is over. What is the result? The summer season was not much, the earning even less. I was just the same as in the year preceding—healthy, contented, but with nothing in my pockets! What would the year 1909 bring forth?” With the help of Dr. P., Konrad Kain procured a spot on the 1909 Alpine Club of Canada summer expedition to the Rockies, and amidst some skiing and climbing, earned and borrowed enough (150 Kronen) for the trip over. On May 29, 1909, he left Vienna with a large traveling bag, chest, rucksack, and two ice axes.

From 1909 to the 1930s, Kain climbed with members of Alpine Club (UK), Canadian Alpine Club, New Zealand Alpine Club, American Alpine Club, and the Appalachian Mountain Club, exposing to the English-speaking mountaineering world the new techniques of safely climbing multi-pitch rock routes primarily with one “all-alone” guide. He created strong partnerships with his clients that enabled new standards of difficulty to be overcome in the mountains. By all accounts, Kain was a great storyteller and a talented guide who worked harder than thought humanly possible, always maintaining a positive attitude no matter what the conditions. He once wrote that he enjoyed trapping in the Altai Mountains in Siberia more than mountain guiding, but nothing could be compared to the twelve-hour days smashing rocks underground of his prior life. Just months before he first left for Canada, he wrote in his beginning English, “I do no more want a work in the stone breaking.” And indeed, he never had to.

Appendix/Maps/More images:

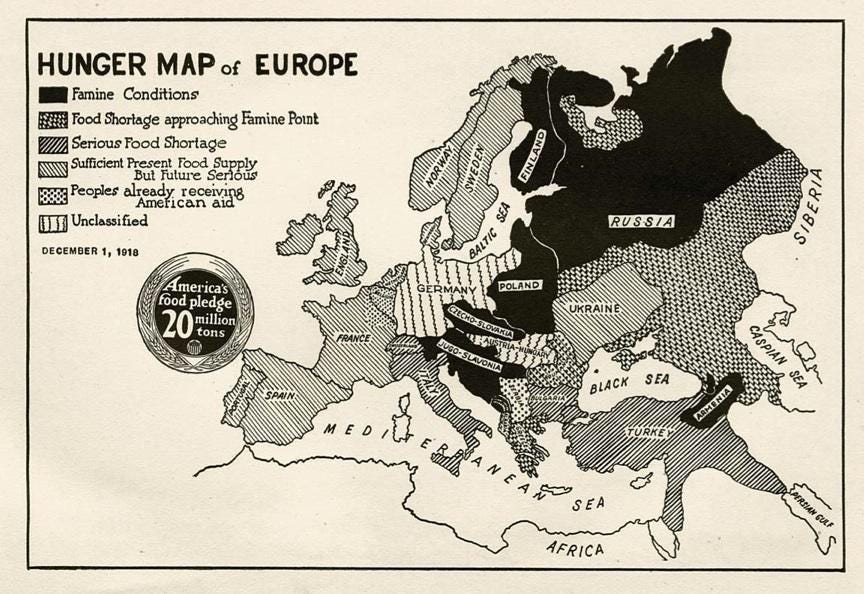

Altai 1912

In the Smithsonian archives, the Altai trip is summarised: “The expedition was a joint effort of the United States National Museum and the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard during the summer of 1912, to study sheep, ibex, and other large game in the Altai Mountains of the Russian and Mongolian region of Asia. The collection of small vertebrate animals, including birds, was also an important goal on the expedition. In total, around 350 mammal specimens were collected. The group departed St. Petersburg on June 8th and headed east. In total, the trip lasted four months and continually faced harsh weather conditions throughout the mountains. The long journey to the "scene of operations" resulted in only around thirty-five days of actual collecting. However, during the expedition an important collection of mammals was made, including thirteen new species and subspecies, along with others previously unrepresented in American museums. The expedition's routes followed that of the Demidoff and Swayne's "sporting" expeditions from 1900-1904. This included embarking Novonikolaevsk aboard a steamer on the Obi River, reaching Bisk, Kosh-Agatch, and the Chuisaya Steppe of Mongolia. Participants in the expedition included Ned Hollister (Assistant Curator, U.S. National Museum), and Dr. Theodore Lyman (Harvard University), Conrad Kain (Hollister's assistant), a Russian interpreter, and four native Tartars and Kalmuks.”

Full list of Conrad Kain’s climbs as compiled by Thorington:

REFERENCES (except journals, etc. where noted)

Where the Clouds Can Go, Conrad Kain and J. Monroe Thorington, 1954 (reprint from 1935 edition).

CONRAD KAIN: LETTERS FROM A WANDERING MOUNTAIN GUIDE 1906-1933 Zac Robinson 2014.

Fred Beckey in the Bugaboos

More Kain Portraits:

John Middendorf is a man of many talents. This is a great story

Josh Armstrong

John, Another out-of-the-ballpark story.

Sallie Greenwood