Trango 1987 (part a)

Trango History Series

Author’s note: The concept of a “Grade VII” wall didn’t exist until the mid-1990s, during a boom of wild multi-day bigwall routes around the world climbed “alpine style’ living on the wall for extended periods through storms on bigwalls using the latest portaledge technology. There had always been a differentiation between routes that were ‘sieged’ (i.e., fixing ropes up the wall bit by bit, sometimes entirely to the summit, with a comfortable basecamp at the end of each day vs. the more committing ‘alpine bigwall style’). But by trying to define (and to answer the pesky media question of ‘What was the first Grade VII?”), it was clear that many bigwall routes going back to the 1970s were Grade VII bigwalls by any definition, even though graded as Grade VI by the first ascensionists. When asked, I always referred to Charlie Porter’s ten-day solo climb on the 800m north tower of Asgard in Baffin Island in 1975 as perhaps the first Grade VII—big, remote, and highly technical—and climbed in a bold and committing style (and because he was a big hero of Yosemite where I lived and climbed for many years). Although who is to say the east wall of the Central Tower of Paine in Chile climbed in 1974 or the west face of Fitzroy in Argentina in 1973, or for that matter, some of the great climbs of the 1960s such as Mount Proboscis in northwest Canada also “Grade VII’s?— a label that seems to require some degree of style. But just as ‘style’ leads to cans of worms, attempts to define an extended adventure with numbers are often futile, and some bold emprises are best shared with contextual stories, my goal for this writing and research project.

in the 1980s…

Trango Tower 1987

After over a decade lull of anyone standing on its summit despite many tries, including three separate attempts in 1986, in 1987 two spectacular new lines were climbed to the summit of Trango Tower.

The most fearsome rock walls on Earth

The 1960-1970s bigwall era, when many big remote ‘Yosemite-style’ bigwalls were first climbed around the world, many were the first-ever ascent of technical high peaks and towers. The ten-day ascent of the east wall of Uli Biaho in 1979 set the standard for the decade that followed, when a new phase of bigwalls up even harder and more dangerous faces began, such as the futuristic Norwegian Buttress on Great Trango in 1984, which set a new high bar of elegant bigwall ‘style’: a small team of extremely competent climbers, with minimal equipment and rope, committing for days and weeks of technical vertical and overhanging ascent, and with no easy means of escape (see earlier chapters).

Fixed ropes

Among the fearsome giant walls of rock first climbed in the 1980s as distinct and more challenging ways to reach a summit, some required first establishing fixed ropes up a significant portion of the wall, often largely due to the nature and conditions of the envisioned line. The measure of the final “push” became the story; bigwall expedition reports often begin in the format: “After traveling and establishing basecamp, for the following ‘xx’ weeks we fixed ropes up to ‘xxx’ meters up the wall, and after returning to basecamp, continued for an ‘x’ day push to the summit.” Such an introduction, with various ‘x’ values, often led to the more exciting tales of the challenges above the safety lines encountered during the final summit ‘push’.

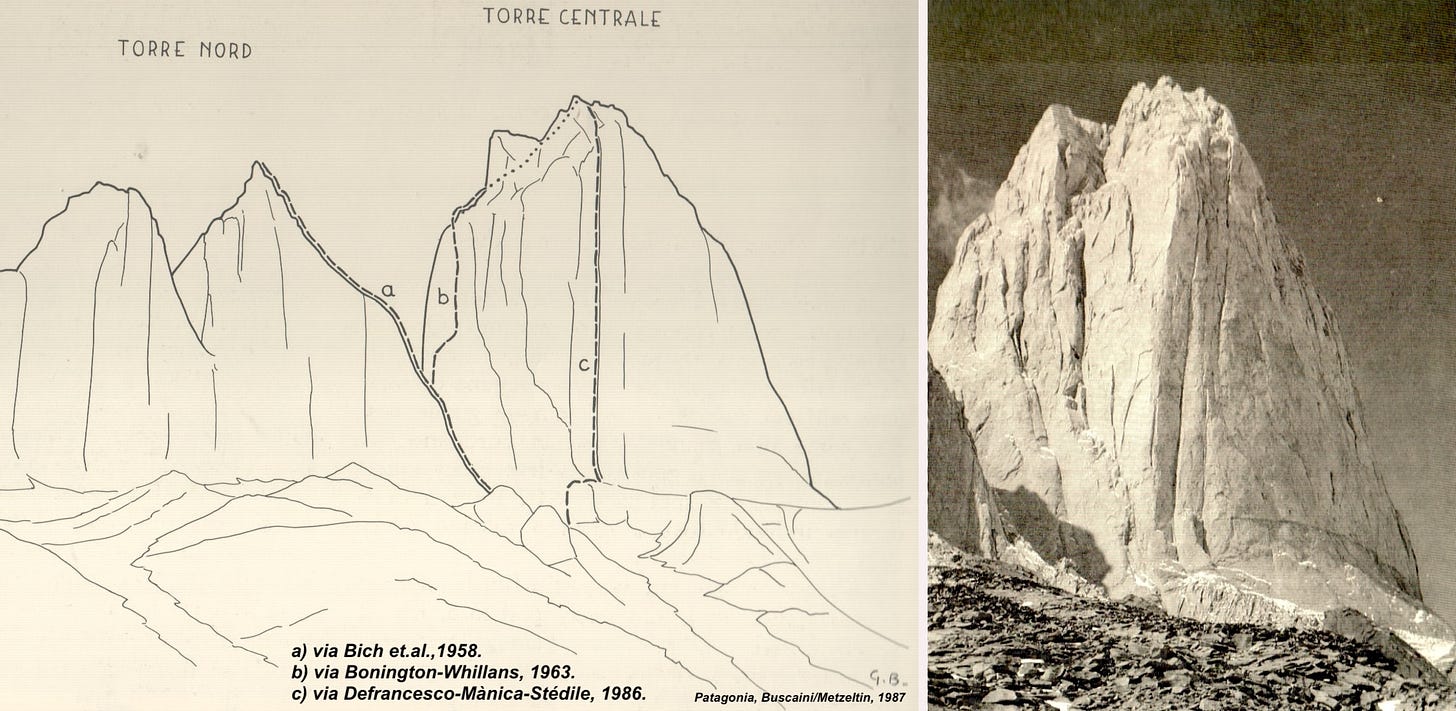

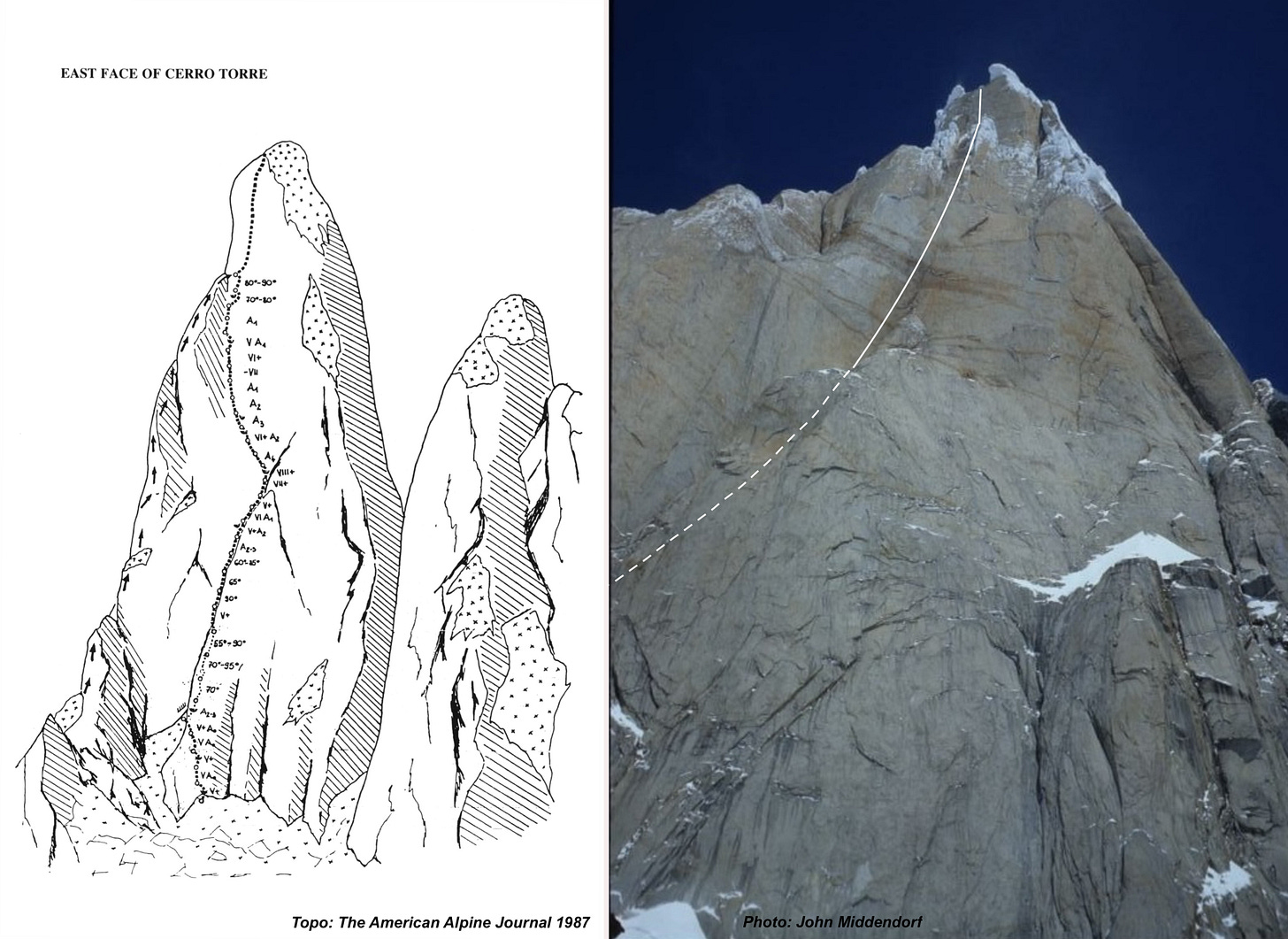

With its concentration of large unclimbed walls involving extremely technical climbing, and with improved access when a bridge over a dangerous river was built and the town of El Chaltén founded to secure Argentine Patagonian territory, the nearby Chaltén massif in Patagonia became a central proving ground. And unlike the remote mountains where teams live isolated on a lonely remote glacier and can drive each other crazy, the annual congregation of global climbers in the area was growing, as was the camaraderie that made the daily grind of approaching and attempting mountains more sustainable over the typical months of continuous high winds and inclement weather. In 1985, Cerro Torre had only been climbed nine times, but by the end of the decade, many more would find their way to its summit, including by a new route up its 1200m steep east wall.

Ever since the controversies revolving around Cesare Maestri and his team’s climb to the rim of Cerro Torre in 1970, where a gas-powered drill enabled long bolt ladders over blank sections to create a direct line sometimes independent of natural features, there was no glory in just summiting a bigwall—excessive bolting would surely wreak the wrath of the fellow climbers, and the camaraderie would end. Climbing the most obvious features up these unclimbed giant overhanging bigwalls, with a minimum of bolts, became the bigwall style accepted by the wider community, even if these lines of weakness were the wall’s most dangerous. Among the small subset of climbers of the 1980s whose main focus was bigwall climbing, who would step up to the attempt the biggest unclimbed faces in Patagonia?

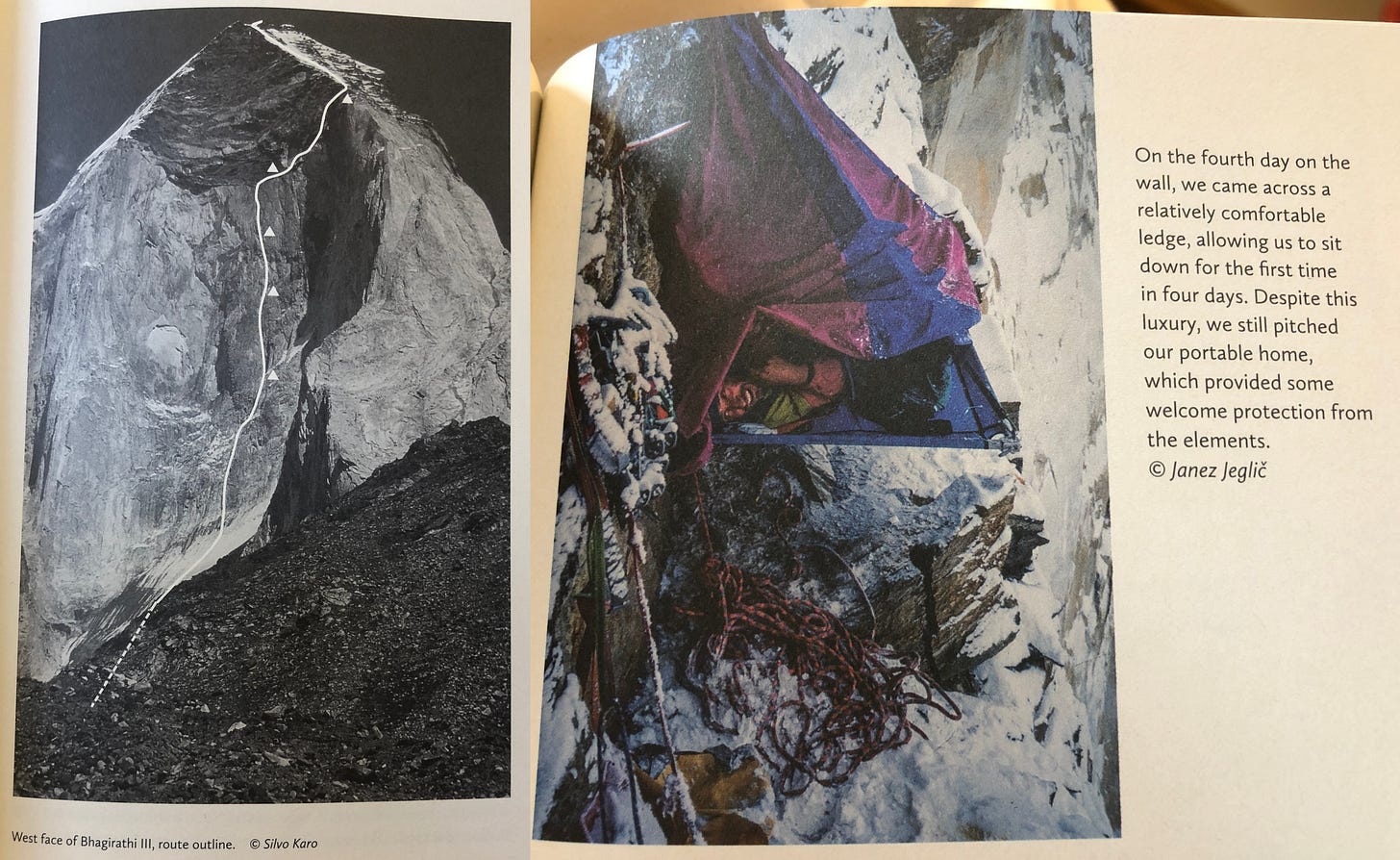

Hell’s Direct (Peklenska Directtissima), Cerro Torre, January 1986

Hell’s Direct is the first climb up the east wall of Cerro Torre in Argentina, climbed in the Patagonian summer of 1986 by a nine-person team from Yugoslavia organized by Stane Klemenc with climber/cameraman Matjaž Fistravec and Dr. Borut Belehar. One only has to sit below the east wall of Cerro Torre for a few hours to witness terrifying tonnage of falling ice and rock. On the east wall, the most obvious feature is a large corner that arches up to the wall’s midpoint. Directly above the corner are ice towers that constantly cleave ice and rock that fall hundreds of meters and funnel into the corner. The only possible strategy to climb this line was to spend as little time in the corner as possible, and then establish fixed ropes on safer sections of the wall for a subsequent push upwards. With alternating teams of two, Silvo Karo, Janez Jeglič, Franček Knez, Pavle Kozjek, Peter Podgornik, and Slavco Svetičič fixed ropes in dangerous conditions.

Klemenc reflects on the first week, “On the following day the invasion of Cerro Torre began. Eight of us carried food and supplies to the bivouac. December 22 was beautiful. Knez and Karo climbed 145 meters of the couloir, luckily surviving a half-day of bombing by ice chunks. Again it stormed for five days. Podgornik and Kozjek were waiting at the bivouac. Every morning they had to dig themselves out. More and more snow and ice coated the face day by day. Although December 27 dawned beautiful, they couldn’t start climbing until eleven A.M. because continuous avalanches thundered down the couloir. The fixed ropes were frozen, in places a foot, into the ice. It took them four-and-a-half hours just to get to the top of the ropes. They managed to climb another two rope-lengths of 60° to 80° ice. The day after, they climbed three more difficult pitches. While the lead climbers worked upwards, Jeglič and Svetičič started up the wall. After 16 hours of hard work, they had fixed the 500 meters of rope on the right side of the couloir down the slabs. No longer would we be exposed to the continual danger in the couloir. Climbing the fixed line would be much faster since the rope would not be frozen in day after day.” (American Alpine Journal 1987).

After a month’s effort establishing 800m of fixed rope up the wall, Janez and Silvo set out from basecamp for the final new climbing to the ice towers, with Knez and the Fistravec following close behind with camera and bivouac gear. Finally, Kozjek and Podgornik joined the team after ascending the fixed ropes and led the final three pitches of Maestri’s bolt ladder to the summit. With another storm looking likely, the team descended quickly, abandoning their bivouac gear and fixed ropes.

This synergistic effort, with alternating teams leapfrogging and strategically making upward progress, then embarking on a commiting final push to the summit, was a successful strategy on the world’s most imposing and dangerous rock wall ever climbed at the time. After their safe return to basecamp, two weeks of storms frustrated their attempts to retrieve the equipment left on the wall. Stane finishes his report in the American Alpine Journal, “After we had struggled back up in bottomless snow, strong winds drifted everything over as quickly as we dug. We couldn’t save the equipment.”

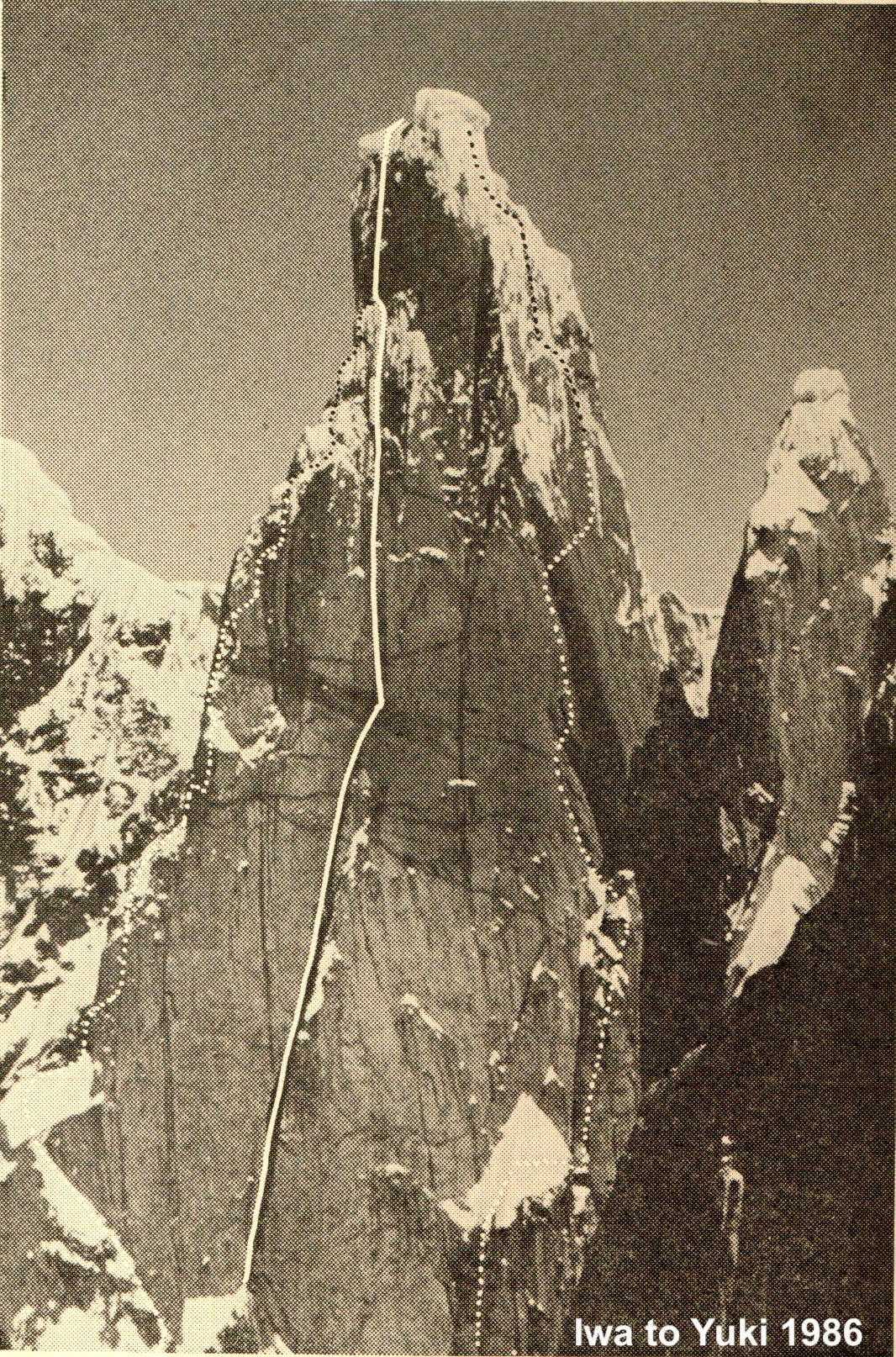

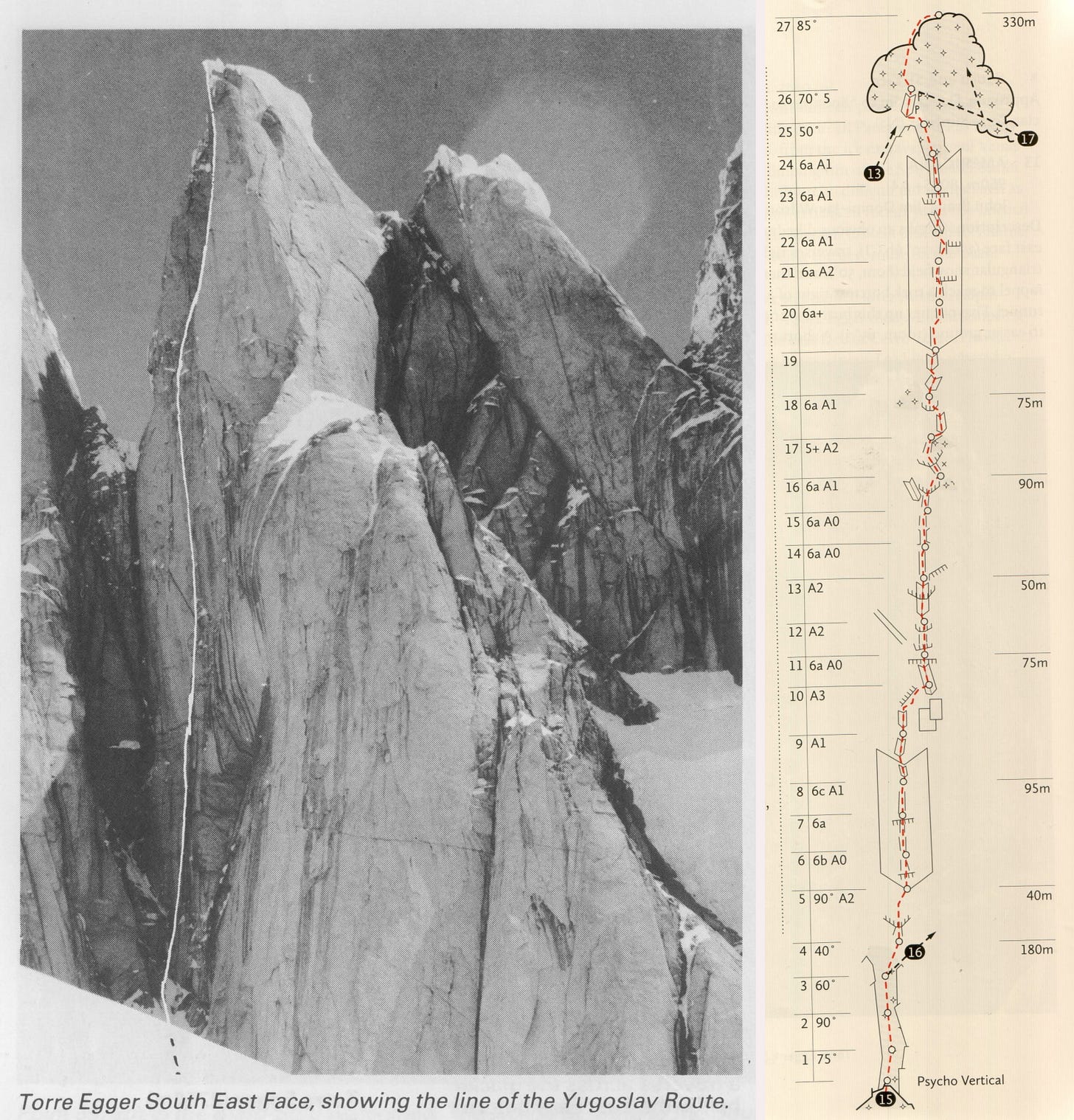

Psycho Vertical, Torre Egger, December 1986

Later that same year, Franček Knez, Silvo Karo, and Janez Jeglič returned to Patagonia and climbed a new route on Cerro Torre’s neighbor summit, Torre Egger. The trio were a dream team for this objective, proficient and efficient in all types of vertical terrain—strenuous free, technical aid, and mixed steep ice and snow climbing, as well as rigging vertical ropes, not a simple task in the Patagonia winds (some of their professional work back home involved technical vertical industrial rigging work). Amidst constant falling ice and rock in the initial section between Cerro Torre and Torre Egger, there were few safe spots to stay overnight, so again they strategized with fixed ropes, eventually establishing 550m of line over 18 days, followed by a final 18-hour technical and committing push from the base to the summit, creating a direct 950m vertical and overhanging climb to the summit of Torre Egger.

The Road to Trango

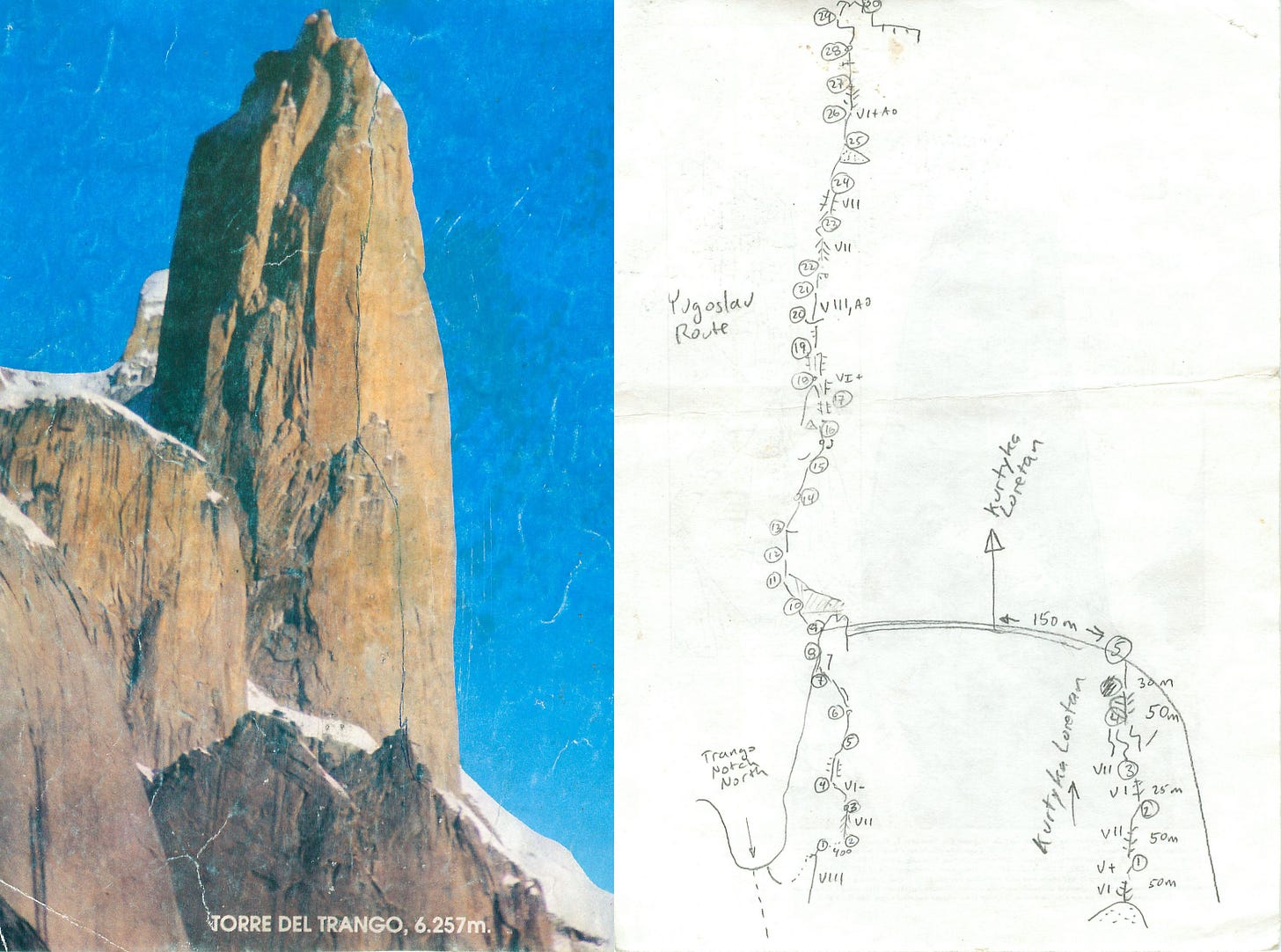

By 1987, Franček Knez had climbed the hardest mountains and walls of the world, including testpiece routes in Alps, Peru, Yosemite, and Patagonia, as well as considerable high-altitude experience, and while his mentees Silvo Karo and Janez Jeglič teamed up for the ascent of the 1200m south wall of Cerro Torre later that year, Franček joined an expedition to the Trango Towers in Pakistan. The second ascent of Trango Towers, unclimbed since the first ascent in 1976, was becoming a coveted prize, and in 1987, a Swiss-French team was also planning an expedition to the area.

The Slovene team comprised of seven people, with a primary four-person climbing team of Franček Knez, Smijan Smodiš, Bojan Šrot, and Slavko Cankar as leader. Dušan Glažar, Slovenska Bistrica, and doctor Zvezdan Pirtošek were also part of the expedition, which began with a long drive from Slovenia to Pakistan (“great adventure and much cheaper than plane” said Bojan). The same tactics that proved successful in Patagonia were employed for this high-altitude challenge. The team picked a stunning line on the ridge that divides the south and east walls of Trango Tower, and from the Dunge glacier, fixed 900m of rope over six climbing days, to the point where “only a day separated us from the summit” (Bojan Srot, 1987). On their summit bid day, Smiljan fell ill, and on June 15, the “well-oiled machine” team of Franček, Bojan, and Slavko ascended the fixed lines where they camped on natural ledges, the next morning continued on the technical terrain above and by 2pm were on the summit.

It was the second ascent of Trango Tower, over a decade since the first. Bojan reflected, “In that moment, I experience all the meaning and nonsense of alpinism at the same time. How much time and money have we sacrificed for the fact that we are now standing here on the mountain! I feel no particular joy; I know it will come after me. I am standing on the top of a beautiful mountain, but I do not dare to say that I have reached any goal, because the goal is something that comes at the very end. Once you reach it, it's game over. But my match is far from over. Now I know that the summit is only here so that once and for all our struggle and suffering is over, that we can return to normal life — and that we can look around and see where we will go tomorrow. We will shift our goal to the future and prolong the race, which is one of the meanings of our lives. And I ask myself: is alpinism really nothing more than an exhibition of the individual, intended for his self-affirmation?” (Planinski Vestnik, Dec. 1987).

Original: V tistem trenutku doživim ves smisel in nesmisel alpinizma hkrati. Koliko časa in denarja smo žrtvovali za to, da stojimo zdaj tu gori! Ne čutim nobenega poseb nega veselja; vem, da bo to prišlo za mano. Stojim na vrhu čudovite gore, am pak ne upam si reči, da sem dosegel ne kakšen cilj, ker cilj je nekaj, kar pride čisto na koncu. Ko ga dosežeš, je tekme konec. Moje tekme pa še zdaleč ni konec. Zdaj vem, da je vrh tu samo zato, da je enkrat že konec našega garanja in trplje nja, da se vrnemo v normalno življenje — in da se razgledamo naokoli, kam bomo šli jutri. Prestavili bomo naš cilj v nego tovo prihodnost in podaljšali tekmo, ki je eden od smislov našega življenja. In vprasam se: ali res ni alpinizem nic drugega kot ekshibicija posameznika, na-menjena njegovem samopotrjevanju?

The team descended in a gathering storm and soon after moved basecamp to attempt the 8051m summit of Broad Peak. The ‘Yugoslav Route on Nameless Tower’ was relatively unreported in the rest of the world, with only brief details in the American Alpine Journal, and almost no mention in the major European journals (perhaps superseded by the French-Swiss route, a more widely published climb for that year), but it immediately became legend in the bigwall climbing world, as no longer were the horrors of the clefts and offwidths of the original British route imagined as best means to climb Trango. The newly established line was clearly a more elegant and cleaner route, visible even in distant photographs, with rumors of few offwidth cracks (which often tend to be full of ice) and with most of the cracks on the route hand-size or smaller, perfect for most climber’s growing gear-racks of small camming devices. Despite little published information about the climb, once the line was seen, it was a clear ride to the top via natural features, and like in other areas in the 1980s, word-of-mouth was the honored way to transmit bigwall beta. Originally coined the “Via degli Jugoslavi”, and until the 1990s known as the ‘Yugoslav Route’, the Slovene Route (1987) is now one of the most popular routes in the Trango Towers (footnote).

Footnote: Regarding the naming of the “Yugoslav Route”—in 1991, after a public referendum supporting independence from Yugoslavia and a Ten-Day War, Slovenia became a sovereign nation, and these routes are now known as the Slovene routes. On naming, Mire Steinbuch writes, “As far as I know, not one name of the Yugoslav Route has been changed into another one although climbed by Slovenian alpinists be it by themselves be it in mixed teams of other Yugoslav nationalities. Back then were different times when Slovenian alpinists sometimes invited climbers from other republics into expedition teams as an excuse for asking for money in Belgrade such as the 1979 Everest expedition on the West Ridge which was climbed by Slovenians, although there were also three members from other republics. It bears the name the Yugoslav Route aka West Ridge Direct. So, I think it is not disrespectful to call Franek Knez's route the Yugoslav Route. After all, it was Francek and his team that named it so.” Later adding that both names coexist, though the Slovene route is preferred.

postscript:

In the 1980s, routes that involved fixing rope left behind on the summit bid were not without controversy, and the use of fixed ropes on the walls of Patagonia, a common practice on the Himalayan giants, was shunned by many in the Patagonian climbing community. Some were outraged by the abandoned ropes on Hell’s Direct, but on Psycho Vertical, the team went back up the next day into the danger zone to clean the route of their ropes, an act that takes special courage after the objective is achieved. (footnote).

Footnote: Some writers barely recognized the Slovene ascents: in Mountaineering in Patagonia (1993), Alan Kearney completely ignores the dangerous “Diedro del Diablo”, a 900m line on the east wall of Fitzroy climbed by Franček Knez, Silvo Karo, and Janez Jeglič in 1983, and only lists the east wall of Cerro Torre and the Slovene route on Torre Egger in small print in an appendix. Today, these climbs and climbers are widely recognized as some of the most significant of the era, though styles that involve fixed ropes evolved, and by the 1990s abandoning ropes fixed on a bigwall after an ascent was less common (as were extensive fixed rope ascents in general).

Rolando Garibotti notes of the 1980s in Patagonia, "In early 1981 Englishmen Phil Burke and Tom Proctor completed some of the hardest climbing ever achieved in the area during an impressive attempt to climb the east and north face of Cerro Torre, reaching a point 20 meters shy of the Ragni route. like Bragg, Donini and Wilson, and like Campbell-Kelly and Wyvill who had tried the line before them, they climbed capsule style, relying on some fixed ropes but committing to the wall for the bulk of the ascent. This style was a clear step forward, but the message fell on deaf ears and for the ensuing decade most major new routes were climbed exclusively using fixed ropes, breaking the challenge presented by the height of the rock faces and peaks into more manageable pieces.” (Patagonia Vertical, 2012), and today notes that the Slovene routes “are still some of the hardest in the area, and there have been no climbers around in the last twenty years with the skills and experience to repeat climbs such as their South Face route. They are state-of-the-art, even if their use of fixed lines takes a little shine off. The ropes on the east and south face (of Cerro Torre) have not been removed, but likely little remains of them. But to be sure, abandoned fixed lines are a big nuance when climbing up. Of course, we should contextualize them being left in the historic time, when few climbers went there, and there was no thought given to future repeats. Unfortunately, some teams still leave ropes today.”

It should also be noted that hanging bivouac shelters that could withstand severe weather were very rare in the 1980s, and many of the biggest walls of the era such as the east wall of Fitzroy (1200m) by MiguelAngel Gallego & José Luis Gallego in 1984, and the west wall of Mount Thor (1100m) in Baffin Island by an American Team in 1985 also fixed sections of the route as a strategic style for multi-day bigwalls, but the degree to which extra rope was used was often questioned.

(The technology used for the ascents mentioned above, and the climbing styles facilitated by the technology, will be covered in this series…)

NEXT: Trango 1987 (part b)

—the third ascent of Trango via the 1987 Gran Diedre Desplomado on the west pillar by Swiss-French team.

—1987 Part c will cover the team from Japan summited the towering formation that rises above the Baltoro glacier (p.5753), first attempted by a French team in 1983, known as Trango Château or Trango Castle.

Photos from Paul Pritchard and Adam Wainwright’s ascent of the Slovene Route on Trango Tower in 1995:

Gone to soon John. Thank you for your enduring contribution to humanity