Trangos 1988 (part a)

Trango History Series (continuing from 1987)

Reports and gorgeous photographs in international magazines of the inspiring 1987 Trango first ascents spread throughout the climbing community, kindling new awareness of what was possible on the tall and sheer granite cliffs of the Baltoro. By 1988, Great Trango Tower only had three routes to its summits, including the visionary Norwegian Pillar established in 1984. The neighboring Trango Tower, then generally known as “Nameless Tower,” had three elegant and natural lines to its summit (see this page for chronology).

It was becoming clear that Nameless Tower, with its searing 1000m crack lines on all sides, was a futuristic first-ascent arena for the most accomplished global bigwall climbers. 1988 witnessed the first two-person team succeed on a new light and fast ascent of Trango Tower, as well as the first free climb of the tower by a German team; there were also significant geologic discoveries. 1988 also saw a boom of exemplary attempts and ascents elsewhere on the Baltoro batholith (footnote).

Footnote: Up to this time, bigwall teams on these massive remote vertical walls had generally been teams of four people or more, then thought to be more efficient for this type of toiling wall, especially if climbed in alpine bigwall style aka a “push”, so a team of two could always be climbing, while others continuously hauling the heavy kit required for extended weeks and sometimes months living on a vertical wall.

But first, a little geology:

The story of the Trango Towers begins 50 million years ago with the India-Asia geologic plate collision, with the Himalayas rising on the thickening crust on the subducting Indian plate, and the Karakoram rising above the Asian plate. As the two continental plates crushed together, eventually creating the youngest and highest mountains on the planet, the high pressures and temperatures at the base of the crust melted the crust and formed granite. Granite is less dense than the “country” rocks (the surrounding unmelted metamorphic and sedimentary rock), so the buoyant plutons intruded upwards towards the Earth’s surface, forming a gigantic geologic feature known as a granite batholith, a relatively homogeneous contiguous igneous mass lying deep underground. Meanwhile, to the south and north the continental crustal folding of the pre-collision rock continued, forming the giants of the Karakoram: Nanga Parbat, Broad Peak, K2, and the Gasherbrums. (footnote)

Footnote: Mike Searle clarifies: Nanga Parbat is made of incredibly young migmatites on Indian plate. The Gasherbrums are made of limestones mainly north of the Baltoro batholith on the Asian plate. Broad Peak is similar but has a major diorite intrusion ( the vertical black/white line seen on Gasherbrum IV) - older than the Baltoro granites. K2 is metamorphic rock intruded by small white leucogranite dikes similar to the Baltoro granite. Other peaks along the main Baltoro batholith are the Latoks, Ogre, Masherbrum, Uli Biaho, Shipton, Paiyu spires, K7 and Saser Kangri.

Around 20 million years ago the Baltoro batholith was still 25 kilometers underground and began to cool, a process that took about eight million years, during which the batholith remained relatively intact amidst the surrounding chaotic continental folding and faulting. When the batholith finally reached the surface (or rather, the surface finally reached it), further eons of weathering and glacial carving of the young granite shaped the long span of tall vertical cliffs we see today, from Latok and the Ogre in the northwest, Trango Towers and Masherbrum roughly in the center, to K7 and the Charakusa spires in the southeast, comprising the most spectacular vertical granite faces anywhere on Earth.

The geology of the Himalaya and the Karakoram had been of great interest to scientists since the 19th century, but in the 1980s there were still many unknowns, as most geologists had access only to the view of peaks considered “inaccessible” (footnote).

Footnote: Some of the 19th century scientific and mapping expeditions are covered in Mechanical Advantage: Tools for the Wild Vertical, Volume 1 (John Middendorf, 2022). Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/MechanicalAdvantageVol1

Starting the late 1970s, geologist and alpinist Mike Searle, now at Oxford University in UK, began a series of annual expeditions sampling rocks from the high peaks in the region, in order to determine the rock’s chemical composition, as well as the age using radiometric U-Pb dating techniques. Mike spent five summers in the 1980s “trekking and geologizing in the mountains of Ladakh, Zanskar, Kulu, and Kashmir” and had “a pretty good idea of the general structure of the Indian plate side of the collision”, but there were still many unanswered questions about the three-dimensional structure of the Asian plate. In 1985 Mike began a series of expeditions to the central Karakoram range, recruiting some of Britain’s best climbers and alpinists to geologically map the Baltoro batholith and its surrounding mountains.

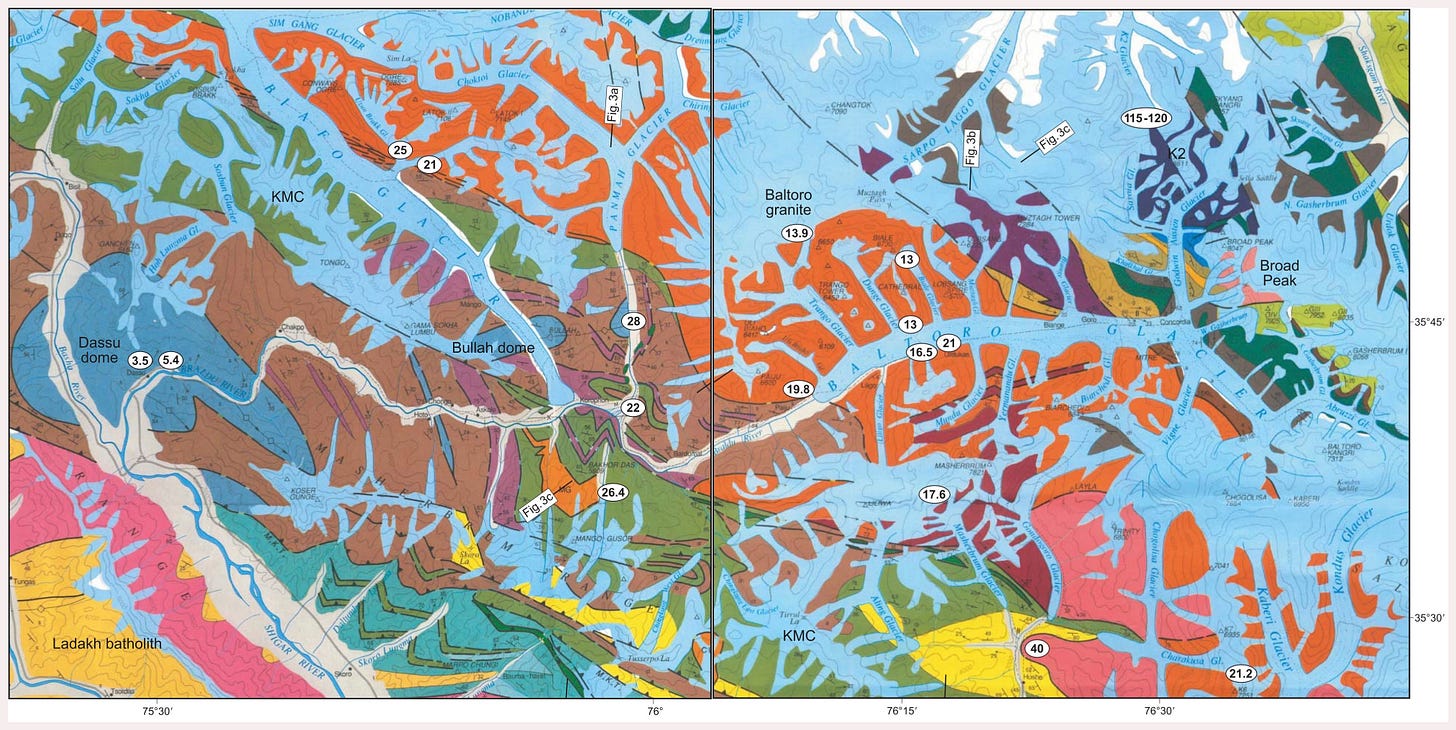

On many of these trips, Mike would transport hundreds of kilograms of rock samples down mountains. Sean Smith remembers, “Beyond Mike’s encyclopedic knowledge of Karakoram geology, is his ability to convince you that an extra chunk of granite in your pack won’t be that bad, as you're only taking it downhill!” In 1988, he climbed to over 6000m on Biale with Nick Groves, Mark Miller, Simon Yates, and Sean Smith, “managing to collect a suite of granite samples from the summit ridge down to the Baltoro Glacier,” which involved traversing a dangerous ridge and ten rappels. Eventually, in 1999, his research and fieldwork resulted in the geologic map below, showing the Baltoro batholith in orange, with Latok and the Ogre in the upper left, and K7 in the lower right. The Trango Towers are roughly in the middle and are the tallest exposed part of the batholith, with “2500 m high cliffs of Baltoro leucogranite exposed in the east face of Great Trango (6452 m) and Nameless (6650 m) Spires” (Searle, 2010).

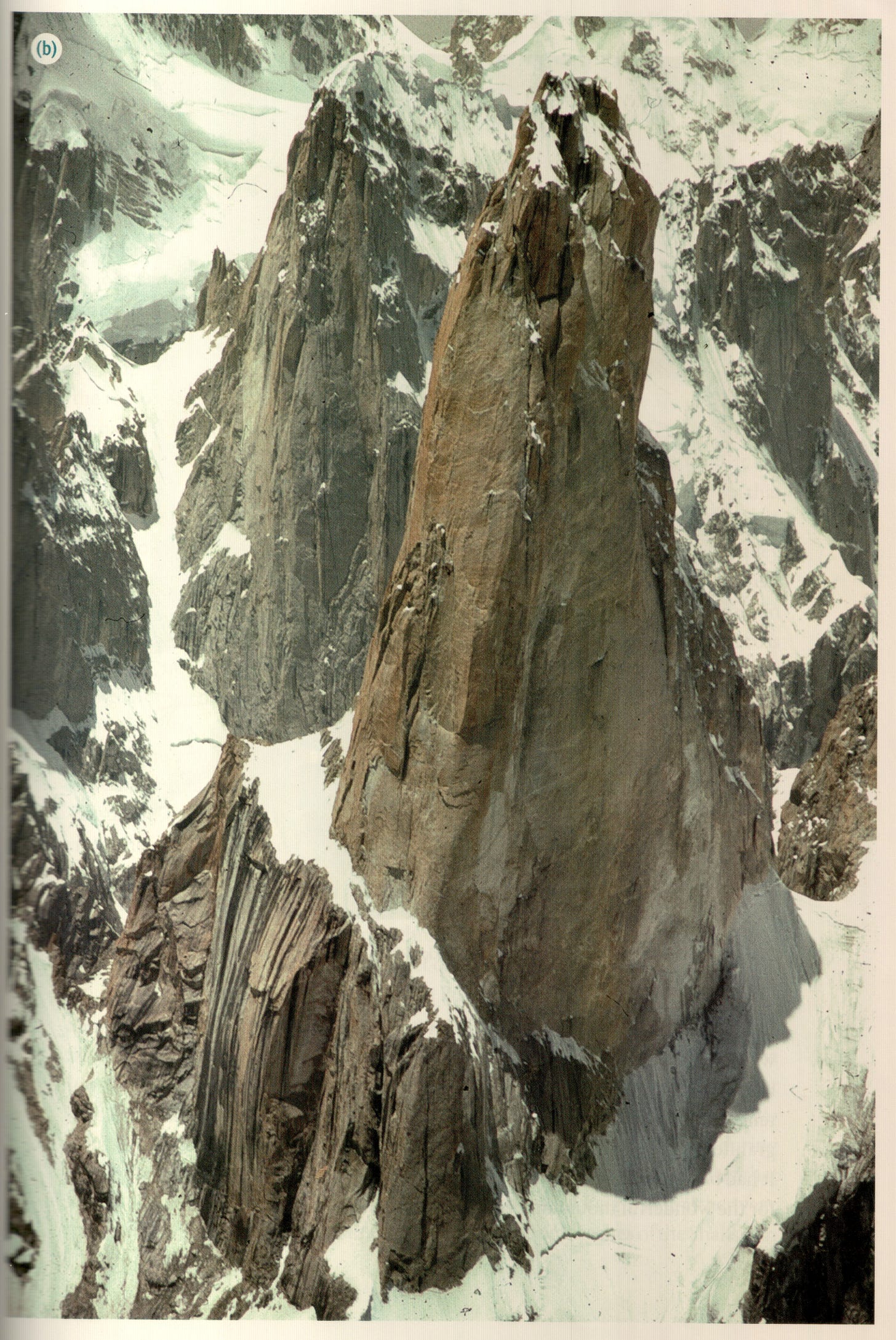

In addition to groundbreaking geologic discoveries, Mike Searle also captured for the first time inspiring views of the Trango Towers from the east, originally published as Baltoro: The Wild Side in Mountain 135 (1990).

Photos copyright Mike Searle, used with permission:

The photos of peaks within the Baltoro batholith that Mike has published have inspired many climbers. Below are a few from one of his scientific papers. SOURCE: Searle, M.P., Parrish, R.R., Thow, A.V., Noble, S.R., Phillips, R.J. and Waters, D.J. (2010) Anatomy, age and evolution of a collisional mountain belt: the Baltoro Granite batholith and Karakoram Metamorphic complex. Journal of the Geological Society, London, vol 167, p. 183-202.

The next part (Trango 1988 part b) will be about the 1988 bigwall breakthroughs in-depth and in context.

In the meantime, below are two 1988 trip reports published in the American Alpine Journal.

The East Face of Trango’s Nameless Tower July 1988

Wojciech Kurtyka, Klub Wysokogórski Kraków, Poland

THE EAST FACE OF THE NAMELESS TOWER of the Trango Towers rises for more than 1000 meters. From June 24 to July 14 Swiss Erhard Loretan and I worked out a new route on that virgin face. This was the first two-man ascent of what may be the most beautiful rock spire in the world.

The 29-pitch line runs up excellent, crystaline, golden granite in a region of unsurpassed beauty. The route rises in the center of the face up a distinctive line of big dihedrals topped by rock roofs and occasionally by huge snow mushrooms that cling precariously to the wall. The upper part ascends a seemingly compact, smooth, golden shield where we were lucky enough to find excellent cracks which we could connect together by three pendulum traverses. Most of the pitches required aid climbing, done almost exclusively with nuts or Friends. It is worth mentioning that the rock is very attractive and promises the opportunity for a totally free ascent in the future. The aid-climbing difficulties at times reached A3. Free climbing at such a high altitude is more difficult to assess. Therefore, I would simply grade it as of UIAA Grade VI.

We spent a total of 14 action days on the climb, split into three sections. Eight were exclusively climbing days. Three were spent both climbing and hauling loads. Another three were used retreating and load carrying. It would be unwise to expect too long a stretch of fine weather in the Karakoram. Therefore, we had to resort to a semi-alpine style. While sleeping on the wall in one or the other of the only possible bivouac places, we progressed day after day, fixing rope and abseiling for the night to the bivouac site. Thus we did not lose the benefit of our hard work when the inevitable breakdown of the weather forced us back to Base Camp.

We set up Base Camp on the Dunge Glacier at 4000 meters on June 20. On June 24, after a night approach with huge, 35-kilogram packs, we reached the base of the tower at 5200 meters. For the next two days, we fixed 300 meters of rope on the initial rock spur and up the snow band. Then on June 26, we returned to Base Camp.

We planned the next trip as the final one, provided the weather would allow it. Of course, it did not. On July 2, with loads of only 25 kilograms but still heavy enough nearly to sabotage us on the fixed ropes, we again reached the snow band, where we arranged our first bivouac site. During the next three days we climbed the big dihedrals. On July 5, we got to the base of the pyramid in a soaking snowstorm. That night, the weather grew even worse. The wall got plastered with wet snow and our bivouac equipment was running water. On the morning of July 6, we had no choice but to retreat, but we had fixed another 300 meters of rope above the snow band.

The third and final try started on July 9. On that day, we ascended the 1200 meters of the approach gully, jümared 600 meters and to end the day climbed one more pitch. To our great joy, this cleared the greatest unknown on the route. On the top of the pyramid we discovered a small rock ledge, detached from the wall. Although it sloped somewhat downward, it was good enough to use for our second bivouac site. Above the pyramid we found the “fantastic crack,” the “double crack,” then the “hidden dihedral” and the “wet slab,” and finally the “Mushroom Chimney.” The latter was choked with big snow mushrooms, but it emerged on the summit ridge. After two ice pitches and an unexpected 25-meter-high rock step, we reached the summit at three P.M. on July 13. On the last rock step, we joined a previous route and found old pitons, probably left by one of the successful 1987 teams. That night we abseiled to the bivouac site.

In the night another week of heavy snowstorms began. Still, we managed, after removing three fixed ropes below, to reach the base of the tower in the afternoon hours.

The fresh memory of the days spent on the Nameless Tower prompts me to compare this technically-extreme, big-wall ascent with two-man ascents on 8000-meter peaks. There are those who identify the forward phase of the sport with the 8000ers, a very false conviction to my way of thinking. The Trango climb called for much more versatile technical and physical faculties. The tactics on the Trango Tower were much more intricate since the wall section, though lower, was much longer and required much more gear. Even more surprising, the Trango climb demanded, at least from me, much harder physical effort than any of the 8000ers. We two carried 120 kilograms of food and equipment and each of us jümared 3000 meters. We worried about rope wear on the knife-sharp crystaline granite. We took occasional falls as our finger tips suffered in this heavy work.

Nameless Tower, Trango Towers. September 1988

Hartmut Münchenbach, Deutscher Alpenverein

Our expedition was composed of East German Berndt Arnold and West Germans Kurt Albert, Wolfgang Güllich, Wolfgang Kraus, Thomas Lipinski, Martin Leinauer, Dr. Jörg Schneider, Martin Schwiersch, Jörg Wilz and me as leader. Late summer and fall are ideal for the south and west sides of the Trango Towers. We had nearly perfect weather with a few snow showers and only two days of bad weather. These snowfalls made for bad conditions on the northeast buttress of the Great Trango Tower, since the sun no longer struck it at this season. Our climb there failed because of heavy icing. On southern faces the conditions were ideal with warm, dry rock because snowfields had melted. We divided into two groups. Kraus, Lipinski, Schneider and Wilz headed for the Nameless Tower. They chose a combined route. They followed the 1986 Kurtyka route to the snow band and then the 1987 Yugoslav route. They got to the summit on September 3. Albert, Arnold, Güllich, Leinauer and I attempted the Norwegian route on the northeast buttress of the Great Trango Tower. We failed at the beginning of the headwall, 500 meters from the summit because of bad conditions. This must be one of the most difficult Karakoram routes. In 14 days of climbing, we completed 25 pitches, partly free and partly with aid (VII, A3 to A4). After giving up there, we turned to the Nameless Tower. On September 3, we camped on the snow band. After a bivouac on the face, on September 5, Arnold, Leinauer and Schwiersch stepped onto the top, followed an hour later by Albert, Güllich and me. We latter three made the first free ascent of the Nameless Tower (26 pitches, 5.11 to 5.12).

Hi John,

Good article especially the geology bit. In the early 1990s we contributed to Mike Searle's work by carrying pieces of leucogranite and the country rock from below the intrusion down from the summit of Thalay Sagar.

Mike Searle's book, which I'm sure you'll have a copy of is "Colliding Continents", it's well written and explains many of the concepts and ideas in a layman's understanding of the evolution of our understanding of how and when the Indian-Asia collision took place. I did like his way of lowering a rucksack full of samples off Shivling!

Keep up the good articles.

Gordon

Superb stuff, John. Thanks for all the great work you are doing.