Why Tasmania's native forests call for direct action.

Rambles about techniques and equipment by John Middendorf

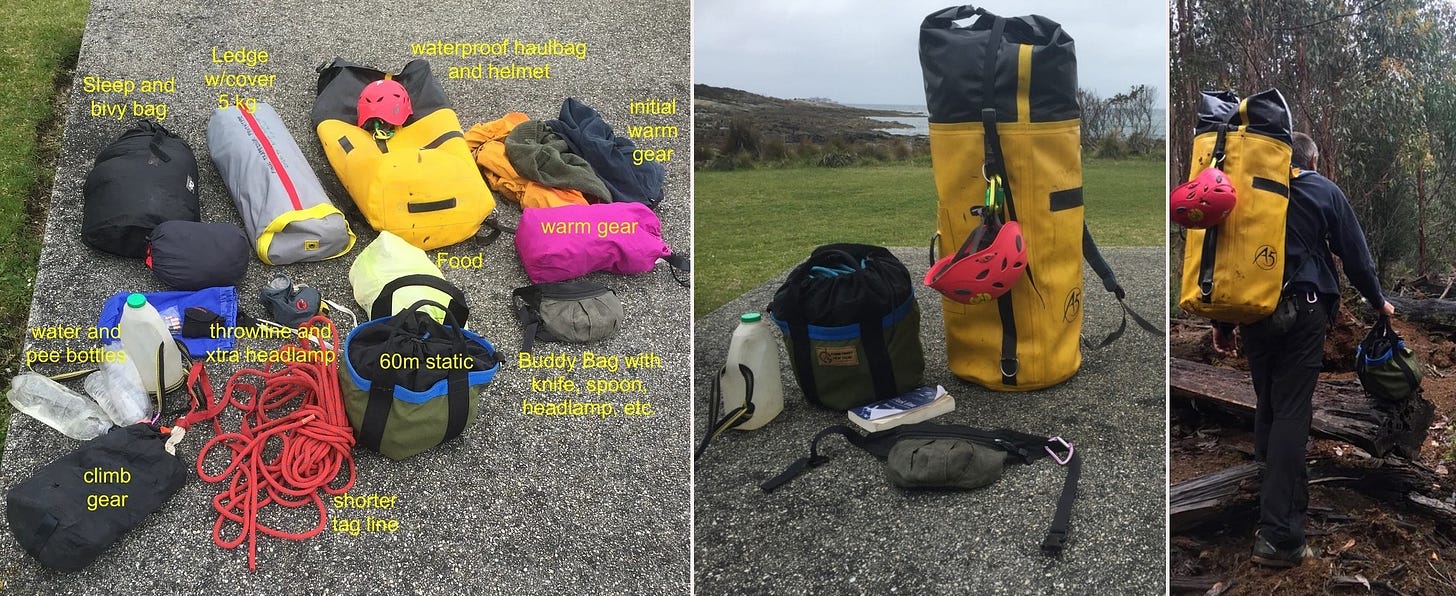

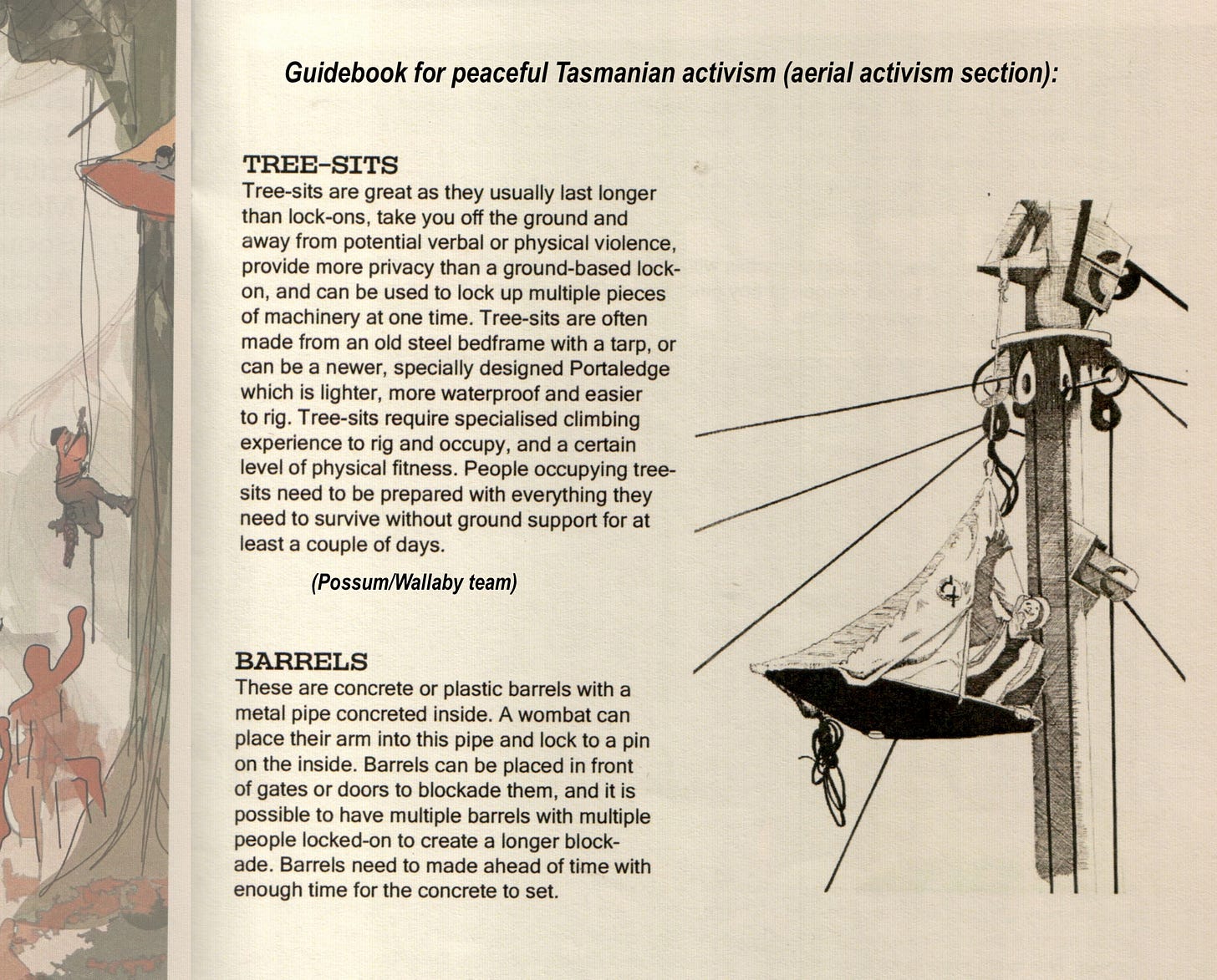

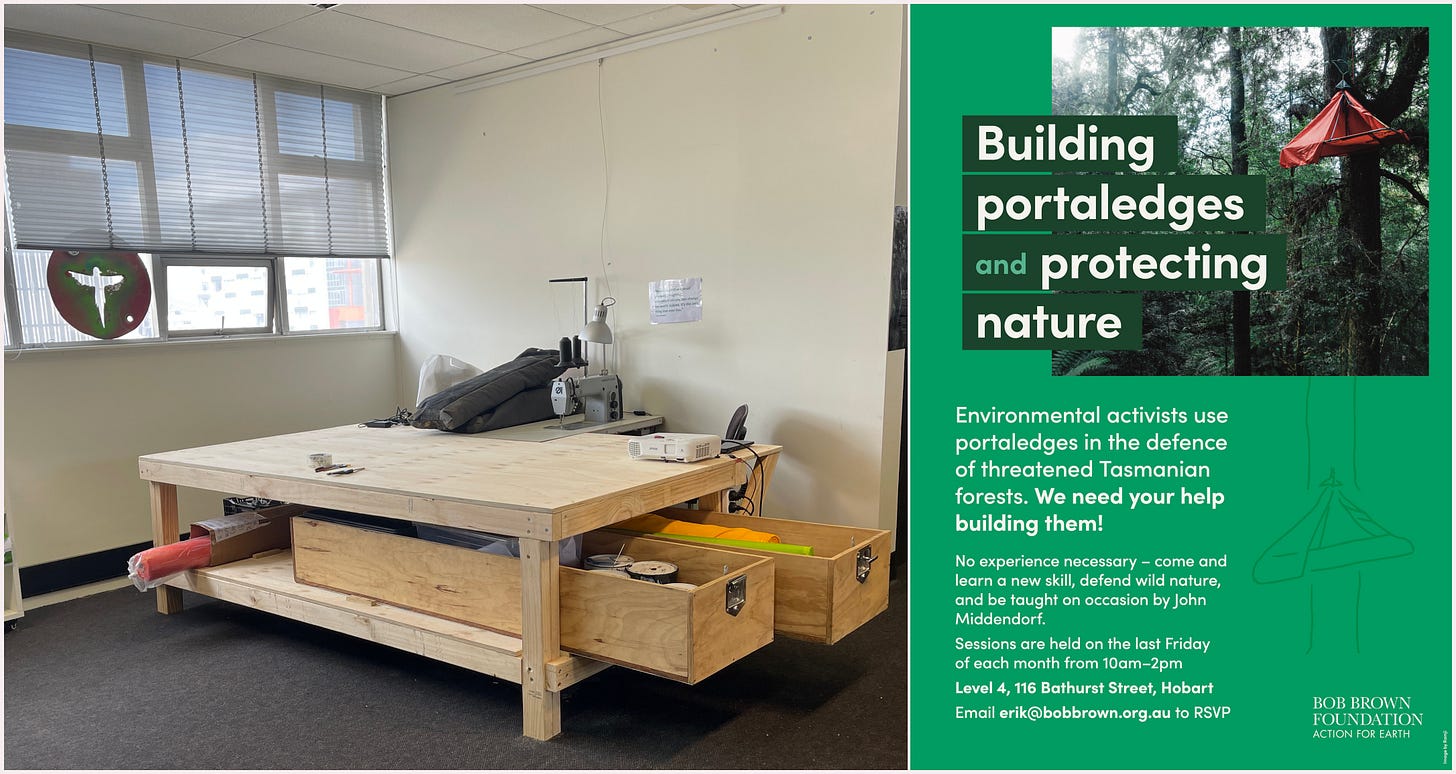

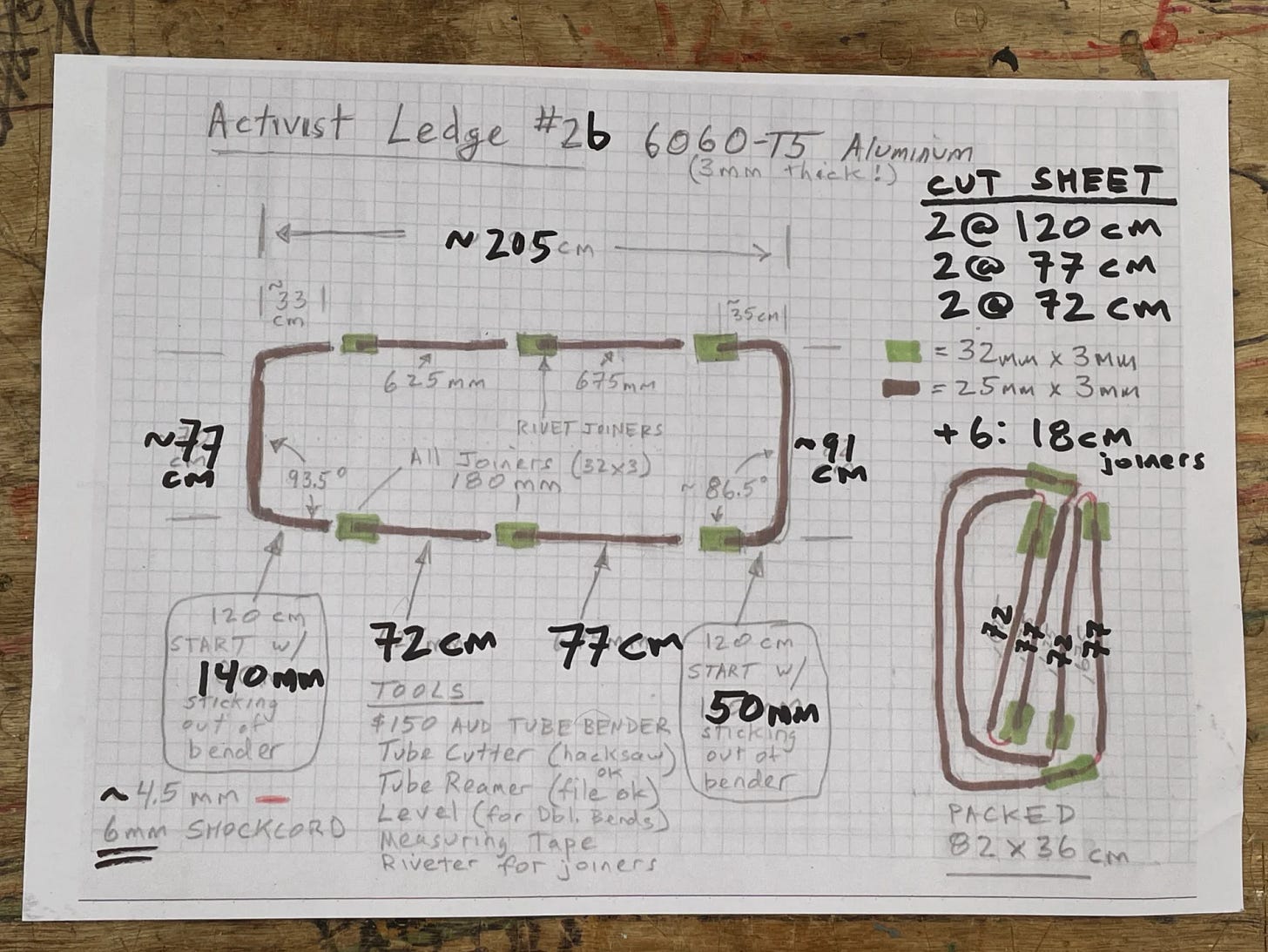

Recently, in my home state of Tasmania, I have been working on systems for a small two-person team to quickly move through the forest and set up a multi-day camp in the canopy of a tall native forest. The portaledges for bigwall rock climbers that I have been making have been helpful, compared with the heavy wood and steel bed-frame technology previously employed for aerial activism, as the weatherproof system reduces the setup time by hours, not to mention being compact and relatively light for transport into remote wildernesses.

Here are some photos of the complete kit for a lightweight team of two to set up an aerial camp for several days in a tall Eucalypt or giant Myrtle (In Tasmania, the Possum/Wallaby Team—the possum is the person in the tree, and the wallaby safeguards the local environment with communication with basecamp).

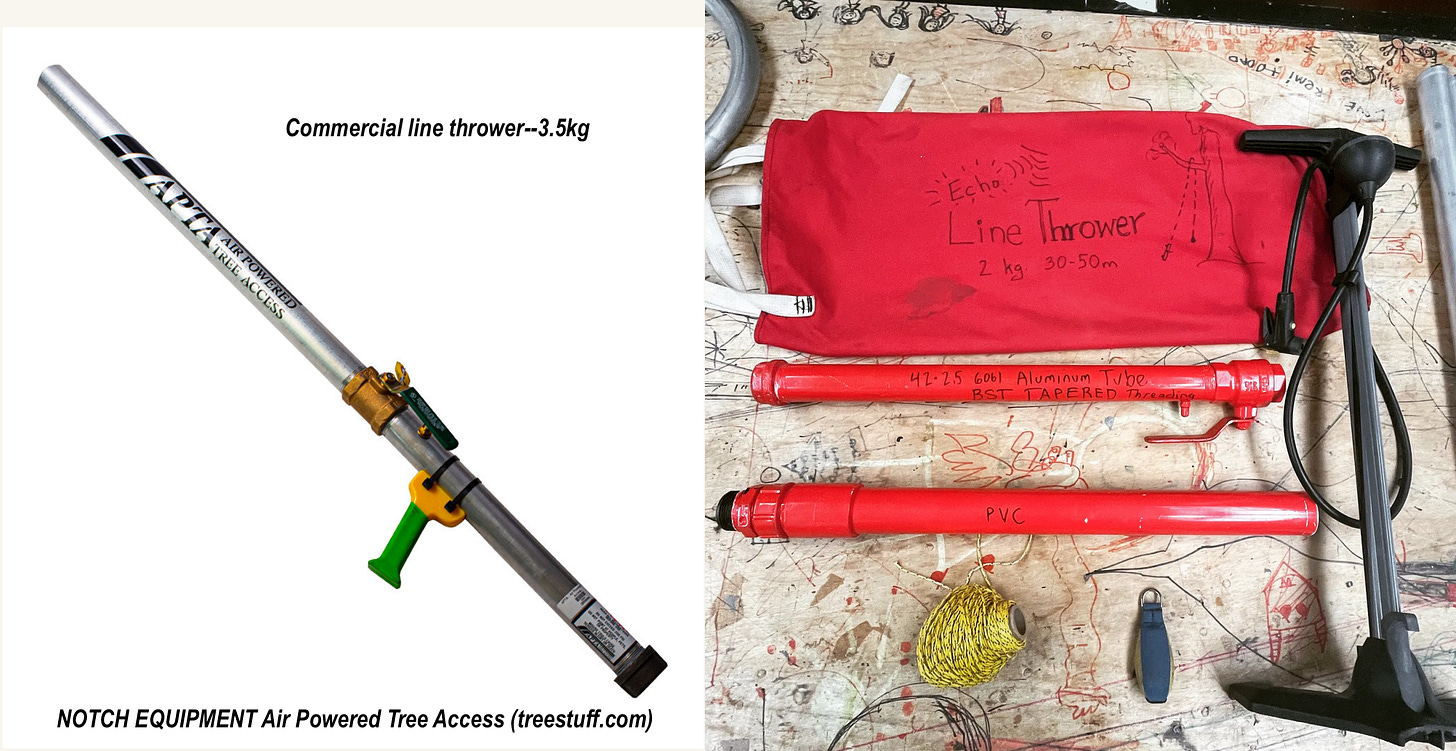

“How do you get the ropes up there?”

A classic question for rock climbers, for tree climbers the answer is a bit simpler. To get the initial line up the tree, we use a pneumatic beanbag thrower, aiming for a high branch. We’ve made custom aluminum tube versions, tested to over 200psi (2x safe pressure), and can easily shoot a line, even by beginners, over a branch 40m+ into the canopy. Once the light line is hooped over the branch, it is used to secure a strong static rope fixed to the branch.

Once up in the tree, it is possible to maneuver higher into the canopy, using advanced tree climber techniques and tools, but I prefer being at the bottom of the canopy—peering down at the diverse and open ecosystem below is especially magic from the canopy’s lower edge: the thick canopy above providing additional shelter and an optimal spot will have a natural opening in a cardinal direction, so it’s possible to gain glimpses of distant rainforest that stretches to the horizon (footnote).

Footnote: Though sometimes in view are open smouldering, wounds where logging has taken place, and where the fire resistant natural rainforest is being replaced with a patchwork of dryer timber (if the goal were to cause wide-scale destruction of one of the largest temperate rainforest that has survived centuries without a major bushfire, creating a grid of tinderboxes within the rainforest would be an effective method).

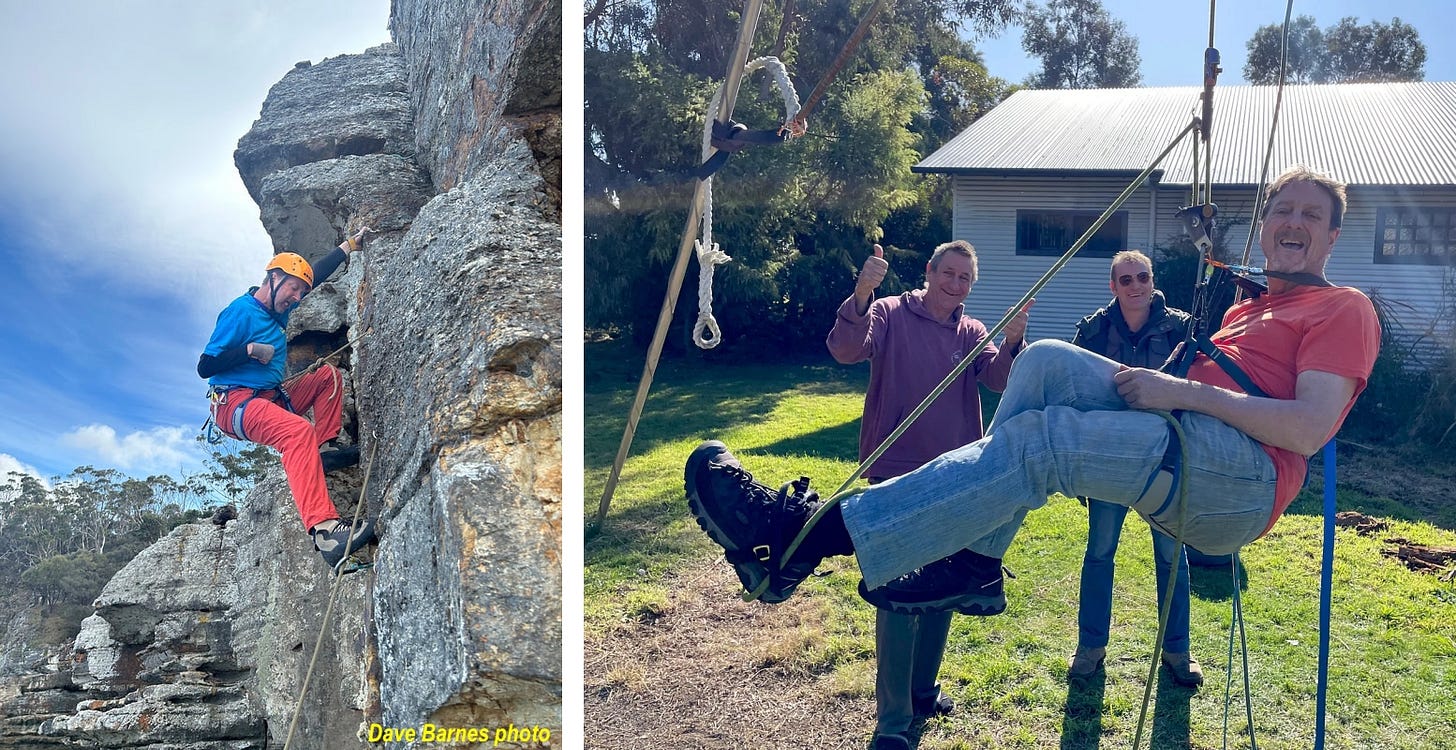

Paul Pritchard and I have been working out ways to set up camps in our favourite trees. We recently worked out a way for Paul to more efficiently ascend fixed ropes, a skill he once mastered on the giant remote rock walls of the world, but now is learning new systems optimized for his alternate abilities that are ever more versatile to help him accomplish his growing list of climbing goals (he recently began leading new routes again, with his first ‘trad’ FA since his accident on his home cliffs in Tasmania, though he is also refining his pure rope ascending skills, the technique he used to climb the Totem Pole in 2016).

Around 2017 I started working with my friend and activist Erik Hayward, first to make weatherproof coverings for his bed-frame and plywood tree-sits. Erik never fails to arrive at my workshop without a housewarming gift—a choice dumpster dive find, or most recently, a huge stump for my anvil, a remnant of an ancient tree that had been left to burn in a recently devastated coupe. Sometimes he offers a fresh wallaby roadkill (the live babies removed and already in the hands of a wildlife carer), and with expert preparation, is the only meat he eats. I met Erik on my first visit to the Tarkine/takayna—I was on a mission to check out the rock climbing in Tasmania’s west, seeking to find the route to Conical Rocks, a remote collection of granite boulders, reminiscent of Joshua Tree but in a coastal environment and exposed to the massive surf of the Roaring 40’s that perpetually pounds Tasmania’s west coast.

On my way, as I was driving along a windy road threading through patches of rainforest and long stretches of logged forest, a hand-painted sign appeared along a side road: “Welcome, come up for a tea and see the forest.” So I did, and first met Erik, and also Lisa Searle, another committed Tasmanian activist who lives in threatened forests whenever she is not doctoring in dangerous regions around the world with Médecins Sans Frontières. Erik and Lisa were blockading a logging road into the roadless Sumac area of the Tarkine, directly protecting the giant trees on the proposed route. A much larger group of activists had recently been disbanded by police on charges of trespass, and now Erik and Lisa were re-establishing the blockade with mostly tip-shop materials not yet confiscated. I was amazed at the high degree of engineering in their rigging, not only of several high tree camps that had been established but also of other architectonic structures such as a 10m tripod blocking the road. Within a few minutes walk from the road into the rainforest along a trail Erik and Lisa had marked, the transformation was sudden, and in the many wild places of the world I have experienced, the intensity of the wave of grandeur amidst takayna’s giant trees matched that of times such as my first visit to the California redwoods, or the first sight of massive foothills of the Karakoram—nature on another scale of beauty and awe.

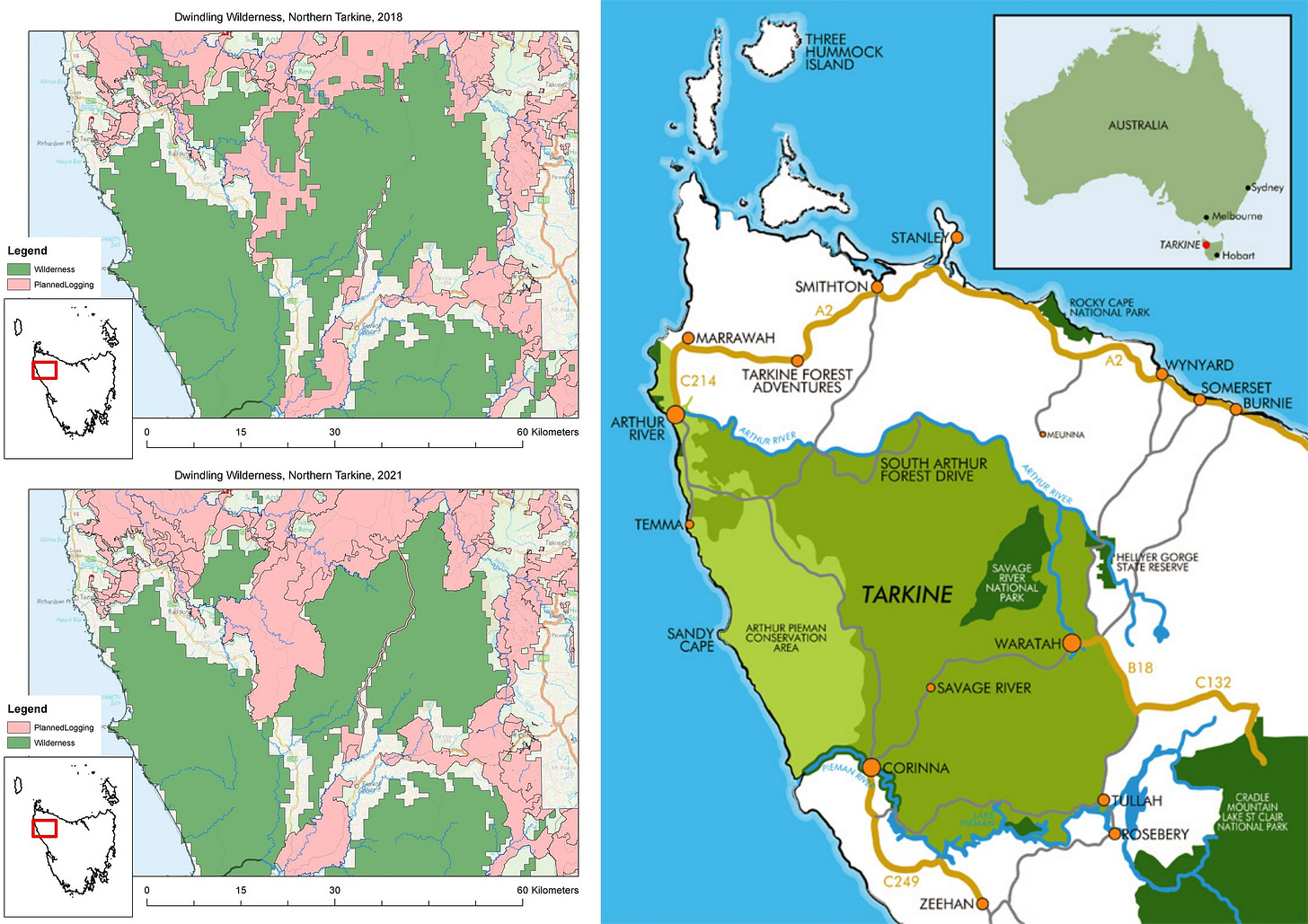

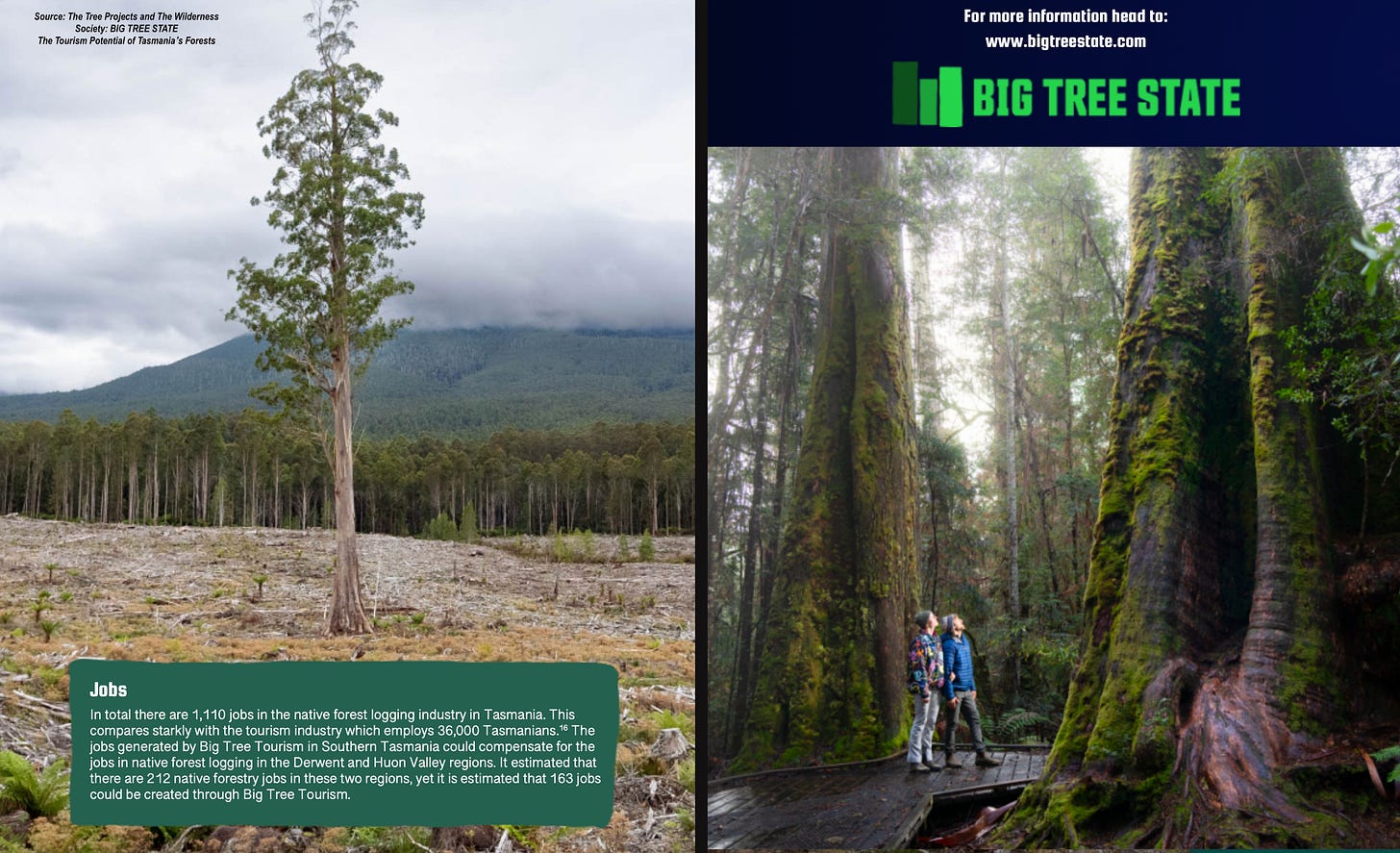

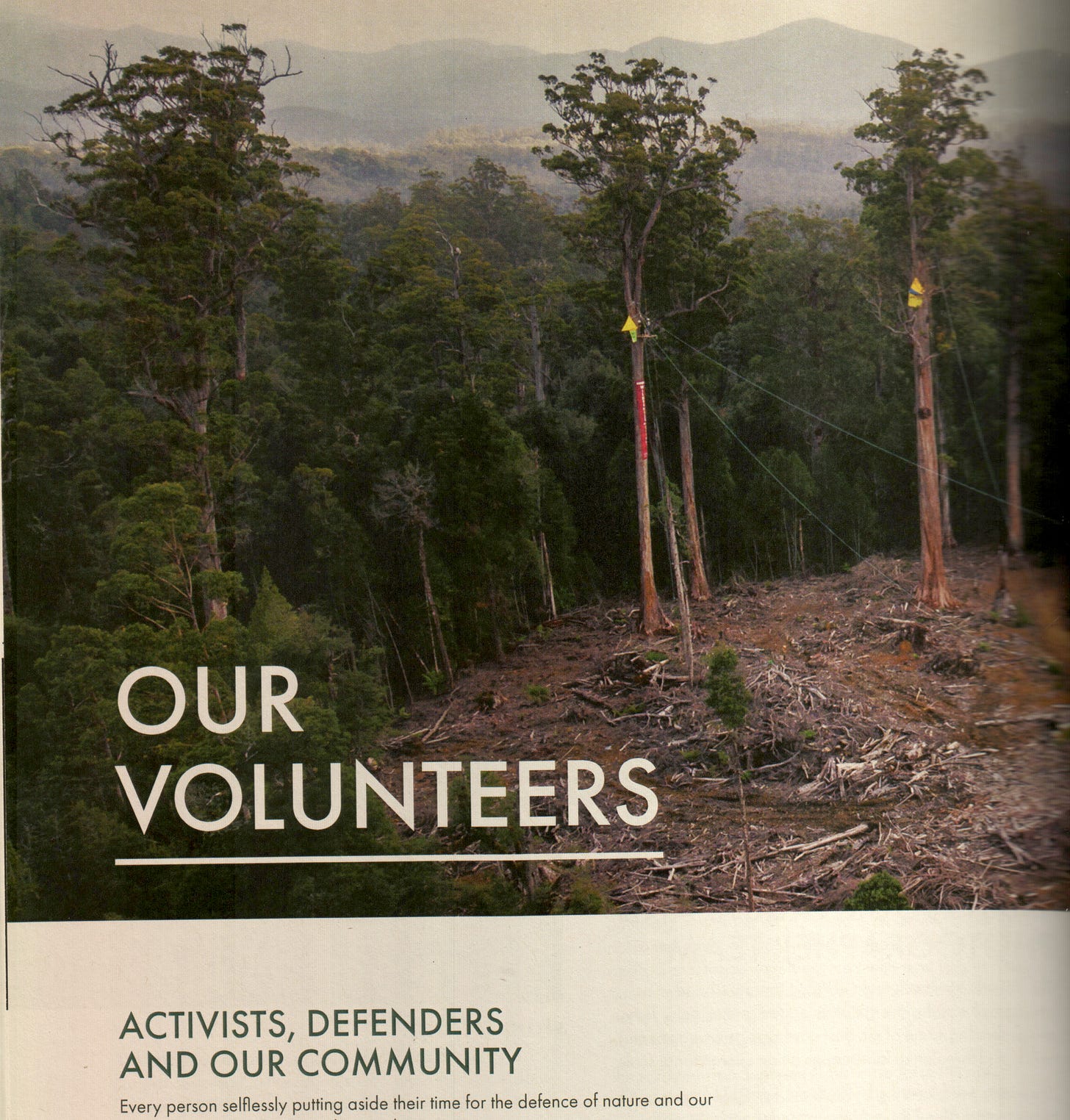

I learned that these lands are Crown Land public forests, with a top-level state mandate to “securely protect conservation values.” A considerable amount of wilderness in Tasmania has been protected, but sadly huge areas of some of the most unique forests in the world, perhaps the best gems of Tasmania’s wild landscapes, are designated “Timber Production Zones.” Not only that, but the Tasmanian government mandates an unsustainable quota of sawlog to be removed from the forests every year, so subsidized companies like Sustainable Timber Tasmania have no choice but to bulldoze into ever more remote native forests for a quota they rarely attain, at a significant financial loss to the state. Most of the native forests end up as woodchip, as naturally hollowed centuries-old trees shatter when felled, so bizarrely, Tasmania, once known for Australia’s finest craft wood, has become primarily a low-value woodchip exporter.

takayna

The most beautiful thing about the area now known as takayna/Tarkine is that, unlike the southern rainforests in Tasmania, where going off trail often requires serious bush bashing (Tasmanians are world champions in this regard), in the takayna, northwest Tasmania’s vast temperate rainforest, the understory is open and easily walkable, and as you wander through it, you will likely be struck with wonder as you approach the realm of an imposing living giant. Sometimes the trees are within a ‘coupe’ and slated for destruction, listed in the annually updated three-year wood production plan, which in aggregate and when extrapolated into future decades, chronicle a grim future for this natural global rainforest treasure.

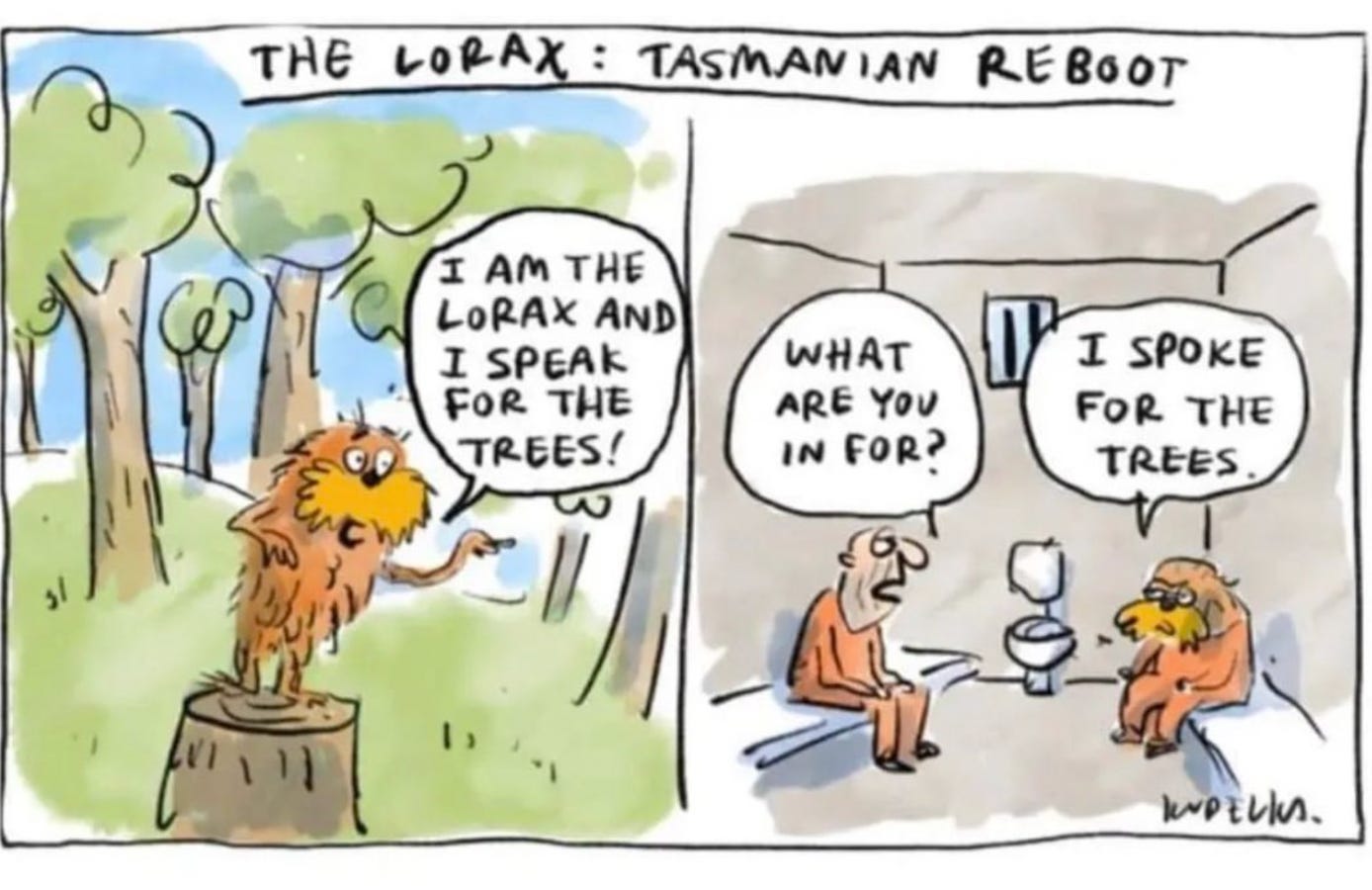

Bob Brown, who needs no introduction as a champion for the wilds, originally coined the term Tarkine for this region, which has now become the more accurate ‘takayna’ (not capitalised as per Aboriginal nomenclature), bringing wider awareness of this region, and the feisty Bob Brown Foundation coordinates multi-tiered campaigns to protect this region (along with many other threatened areas in the southern hemisphere) with legislative change, public awareness, and direct action. Bob still, after decades of challenging encounters and serving in the highest levels of government, is often the first to get arrested by refusing to move out of the way of bulldozers in unique but threatened areas, and inspires others to do the same in defense of the wilds (footnote).

Footnote: For many, the BBF-sponsored annual Canopy Campout (tree camping), Bioblitz (citizen’s science), Art for takayna, takayna Trail, and peaceful and permitted forest training camps are memorable introductions to unique areas with no risk of trespass in Tasmania’s public lands.

Paul Pritchard and I have both visited the takayna/Tarkine many times thanks to Bob—it is a long drive from Hobart, sometimes seven to eight hours, even though the island of Tasmania spans only a couple hundred miles at its widest point—there is still a lot of remote wilderness here. On forest trips, we’re drawn to different trees—sometimes I prefer the more slender ancient myrtles up to about 50m tall, Paul at times has opted for higher camps 70m off the ground in a giant stocky eucalypt. Sometimes there are multiple potential camps in a patch of tall trees, where a group of aerial tree sitters become a community, even though each tree-dweller has incredible solitude in their own giant.

History

Tasmania has a long history of hard-fought ‘battles’ for preservation; many are chronicled in Greg Buckman’s Tasmanian Wilderness Battles (2008), though most of these historical struggles are hardly battles in the traditional sense, as the ‘world’s best practice’ of non-violent direct action (NVDA) have been refined over the decades, often with amiable relations with the authorities. The strictly peaceful methods employed in Tasmania have made a difference, slowing—but certainly not stopping—the march of industry, even in cases where legal mandates of environmental and species protection are clear.

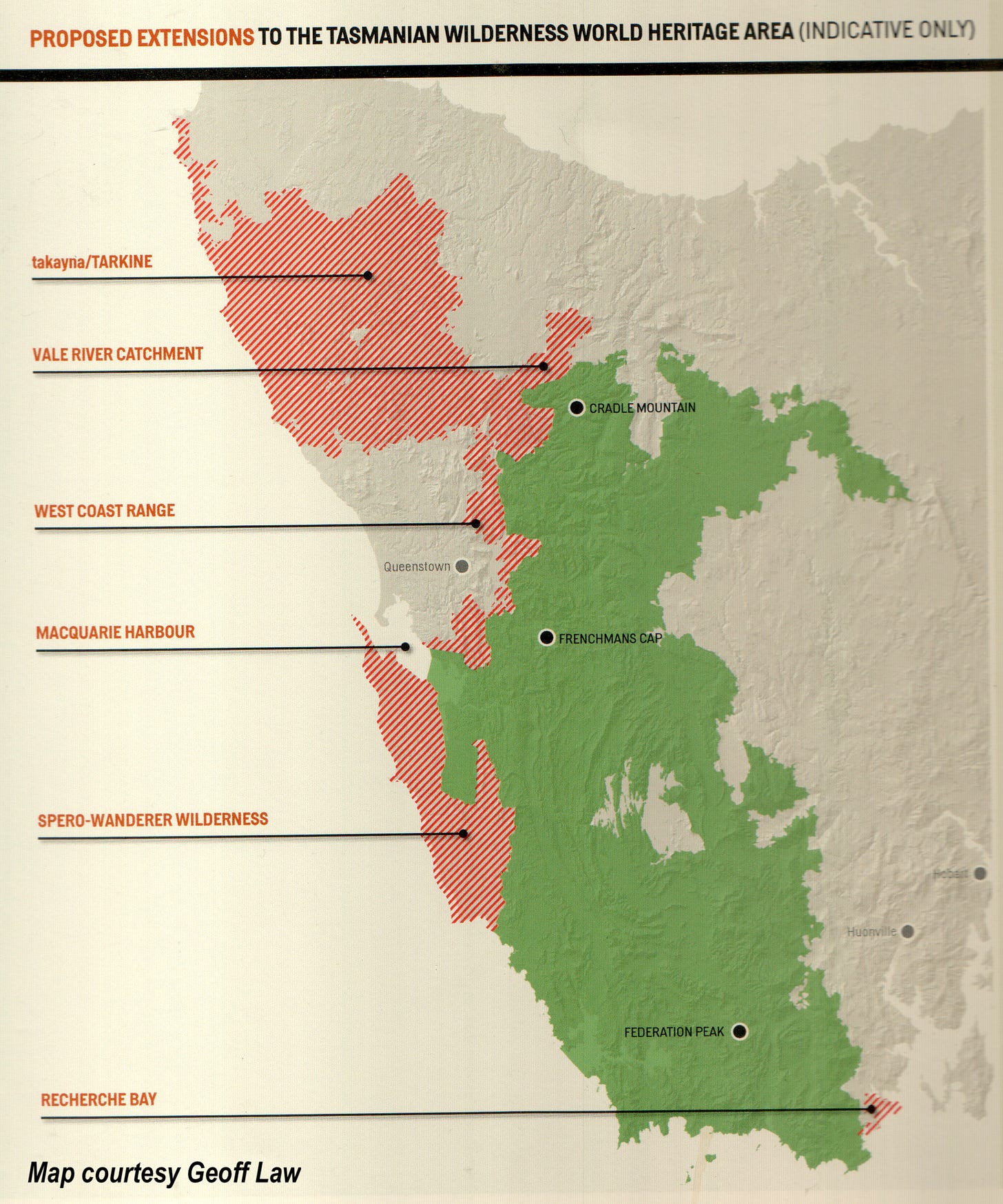

Buckman’s book highlights a pattern going back to the 1950s: the march of progress destroying wild places often reaches a limit, when a broad public outcry necessitates action—often an “agreement” is established, which calms both environmental and industrial stakeholders, but then the march resumes, sometimes with complete abandonment of the environmental side of the agreement. For example, in 2013, the public uproar over the accelerating conversion of massive swaths of native forest into woodchips resulted in a ‘Forest Peace Deal’, which provided foresters with two hundred million dollars (AUD) in taxpayer funds to exit native forestry on Crown Lands, in exchange for nearly a million acres of mostly native forest to put into ‘reserves.’ The public was calmed, and while many believed the reserve status meant reserved from logging, industry advocates clearly saw it as ‘reserves’ of vertical logs, and the following year, the ambiguity was legislatively clarified when the region was redesignated with no hint of reservation as ‘Future Potential Production Forest Land’. Historically, agreements negotiated by citizens and elected environmentalists have slowed the death of the forests by a thousand cuts—but only when the strongest legal boundaries are established, such as World Heritage, does the global voice for protection prevail. Meanwhile, the industry-friendly Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) blueprints the extinction of more species by de facto exempting forestry from external regulation of federal statutes like the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) of 1999.

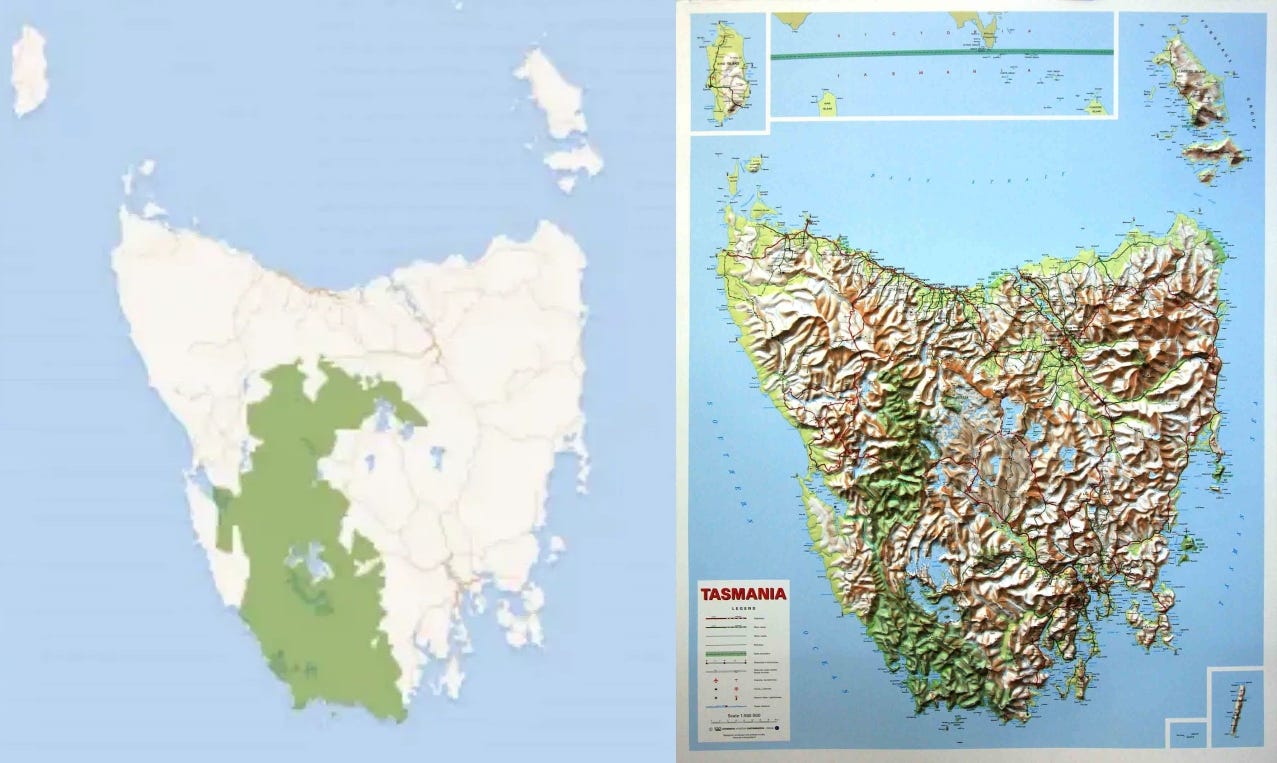

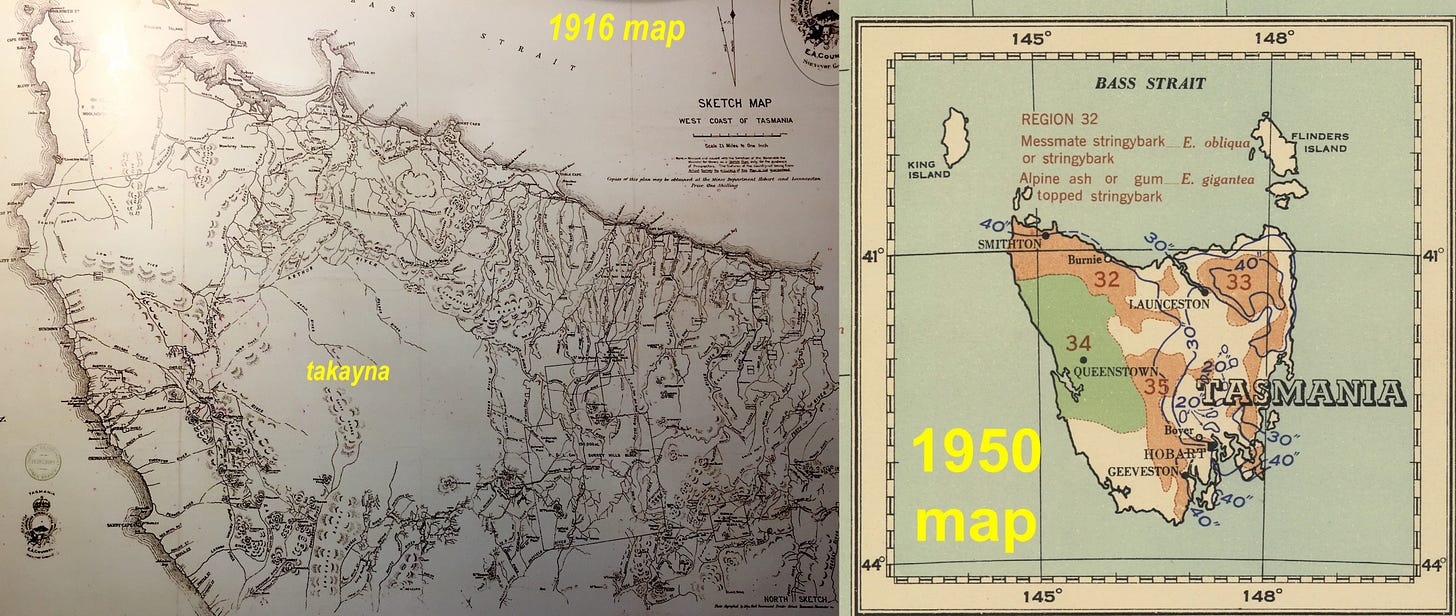

One of the issues in the takayna is remoteness, far from the current tourist circuit primarily due to its still-primitive wildness, with access only being possible more recently from industrial-scale mining and forestry roading. The old maps provide insight.

Newer maps are confusing—I lived in Tasmania for nearly a decade before I realized there was an incredible rainforest in the northwest, the largest temperate rainforest in Australia. Once my family and I had traveled for days to see Queensland’s incredible tropical rainforests, a huge tourist draw for the state, while ignorant of our very own native rainforest close to home—the maps on my wall often highlight World Heritage areas in green, but little else to indicate where vast forests reside in Tasmania.

Geoff Law, one of the main Tasmanian architects of World Heritage Areas, provided me with a more realistic boundary map of regions of the highest conservation value lands in Tasmania. Geoff is confident that The Bob Brown Foundation’s “titanic battle for takayna/Tarkine will ultimately be rewarded by World Heritage status. It's a question of how much can be saved in the interim.”

Current legal protections for Tasmania’s natural landscapes and habitat for endangered species are weak—having been involved with legal wranglings with various US land managers on preservation issues—the Bureau of Land Management in Utah, the National Park Service in Yosemite and Joshua Tree, and the Forest Service in the northwest—the top-level American legislation such as the Wilderness, Endangered Species, Environmental Protection Acts provide various means to legally challenge clear violations of public policy. In Australia, where there is not even a requirement for land managers to inventory natural areas such as mandated at least once a decade by the USA’s 1964 Wilderness Act, and here it seems a bigger challenge to oppose clear breaches of international and national laws. For example, if an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is required (with its high bar to trigger), no alternatives need to be presented, but worse yet, the environmental assessment is often cursorily performed by the proponents themselves (talk about foxes in the henhouse) and fails to identify the significant risks to flora and fauna, or offers only ineffective remedial measures.

Local academics seem to have bought into the idea that “forestry best practice” involves the continuing destruction of ancient natural ecosystems, providing exceptionally effective greenwashing, but anyone witnessing firsthand the impact of clearfelling native forests will see the stated impacts do not disclose the real loss to Tasmania’s greatest resources (footnote). I like to bring my kids up to see these places before they are gone, and was able to visit the remote and unique Rapid River area of takayna before it was logged, and then again after, and it is truly hard not to shed a tear when you think of all the habitat destroyed in the wasteland of shredded stumps and ferns. In one of the massive clearfell coupes a few years ago, my 6-year-old daughter asked me, “The animals—where are they going to go?” I had no answer.

Footnote: Though only a minority of Tasmanians have visited takayna, most feel it is important to improve the protection of Tasmania’s natural landscapes for which the state is well known, providing the lion’s share of tourism revenue, but thanks to greenwash such as native forest timber companies using ‘sustainable’ in their branding, many are unaware of the scale and speed of the actual forest destruction.

Extinctions ongoing

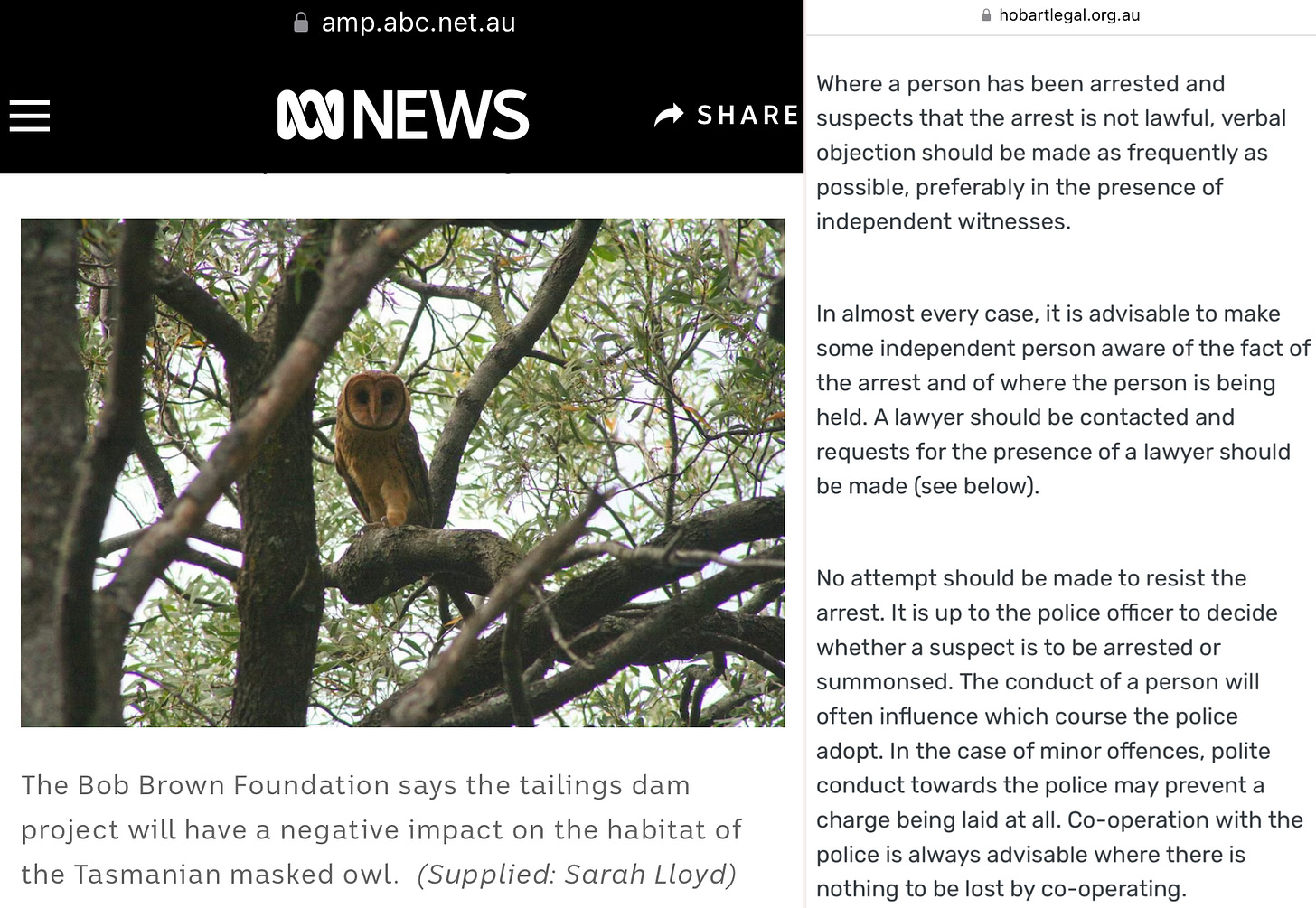

Australia leads the world in the rate of mammal extinctions, and we have seen many examples of citizen science clearly refuting the claims of the “self-regulating” forest industry. Recently Rob Blakers, a landscape and wildlife photographer, stood his ground in an area of the forest now designated as SH050B—AGR (footnote) in the forests of the Eastern Tiers. Working with the Bob Brown Foundation, Rob documented an exceptionally important breeding and feeding site of the critically endangered swift parrot, a species with an estimated 750 remaining birds, destined to be extinct in ten years if habitat continues to dwindle at the current rate. Although the self-regulated management approach published by Sustainable Timber Tasmania claims to “reduce threats to Swift Parrot breeding success”, and “to engage with species experts to improve conservation”, Rob (as one of the most knowledgeable experts), realized they were doing neither as they began logging the area, and after multiple attempts to contact Sustainable Timber Tasmania with no response, he and others blockaded and stopped the machinery for a day. He was arrested for trespassing on public lands, a court date was set, and logging resumed the next day. The Federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has foreshadowed new environmental laws requiring regional forestry agreements to meet national environment standards, but how and when that legislation will operate is currently uncertain.

Footnote: AGR stands for Advanced Growth Retention, a partial harvesting method that converts native forest to a quasi plantation, with old trees isolated or removed and evenly spaced young trees retained in a habitat detrimental to swift parrot breeding. Rob clarifies of the aftermath of the logging of SH050B, an area known to be a Swift Parrot Important Breeding Area (SPIBA): "Virtually all of the large trees here have been felled. The few older trees that remain are isolated and exposed to windthrow." The AGR style of logging was formerly known as “Overstory Removal” prior to Forestry Tasmania’s ‘sustainable’ rebranding.

The Tree Projects, led by Dr. Jennifer Sanger, a forest ecologist, and Steve Pearce, filmmaker & photographer of tall trees, is another organization doing careful citizen’s science in areas that lack independently regulated studies, often discovering and measuring trees with incredible volume and height that should trigger the protection of these ancient trees, yet repeatedly, these special trees are felled without consequence, justified by endless loopholes in Australia’s environmental protection acts.

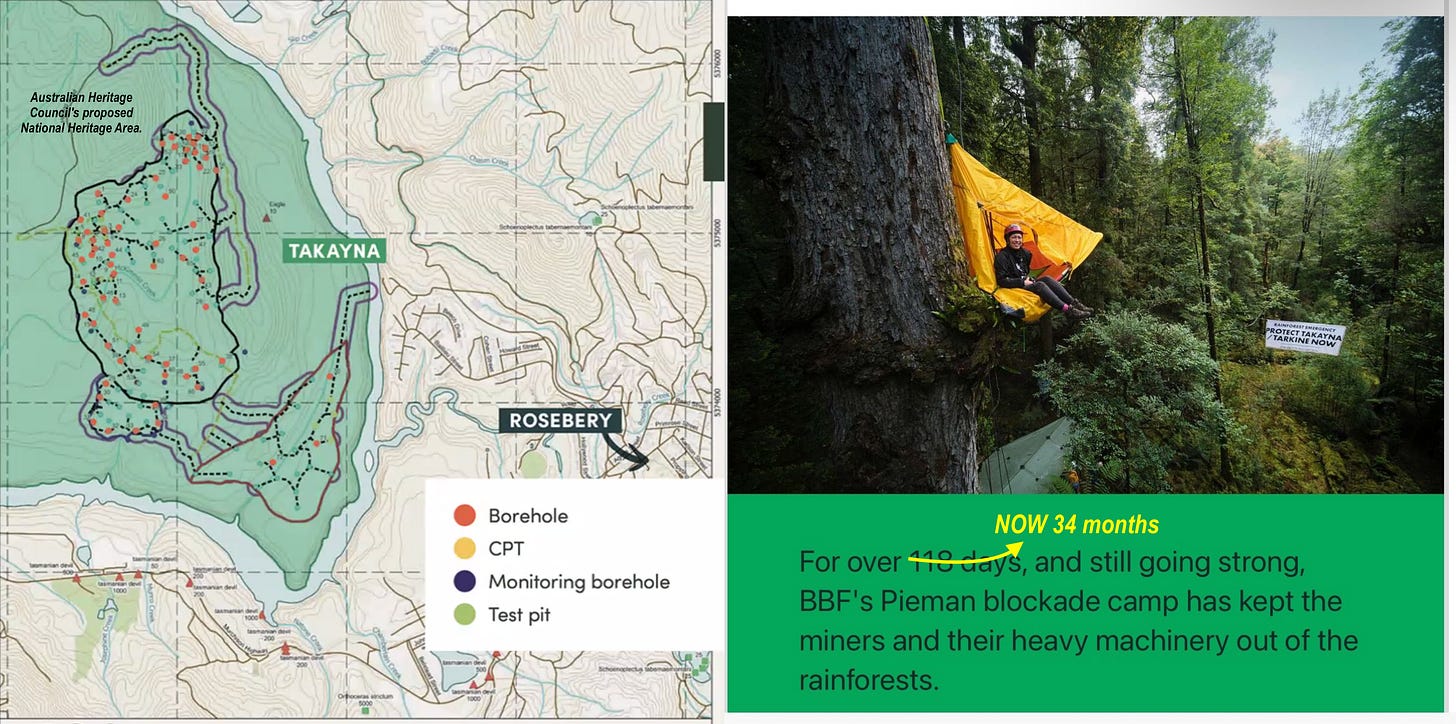

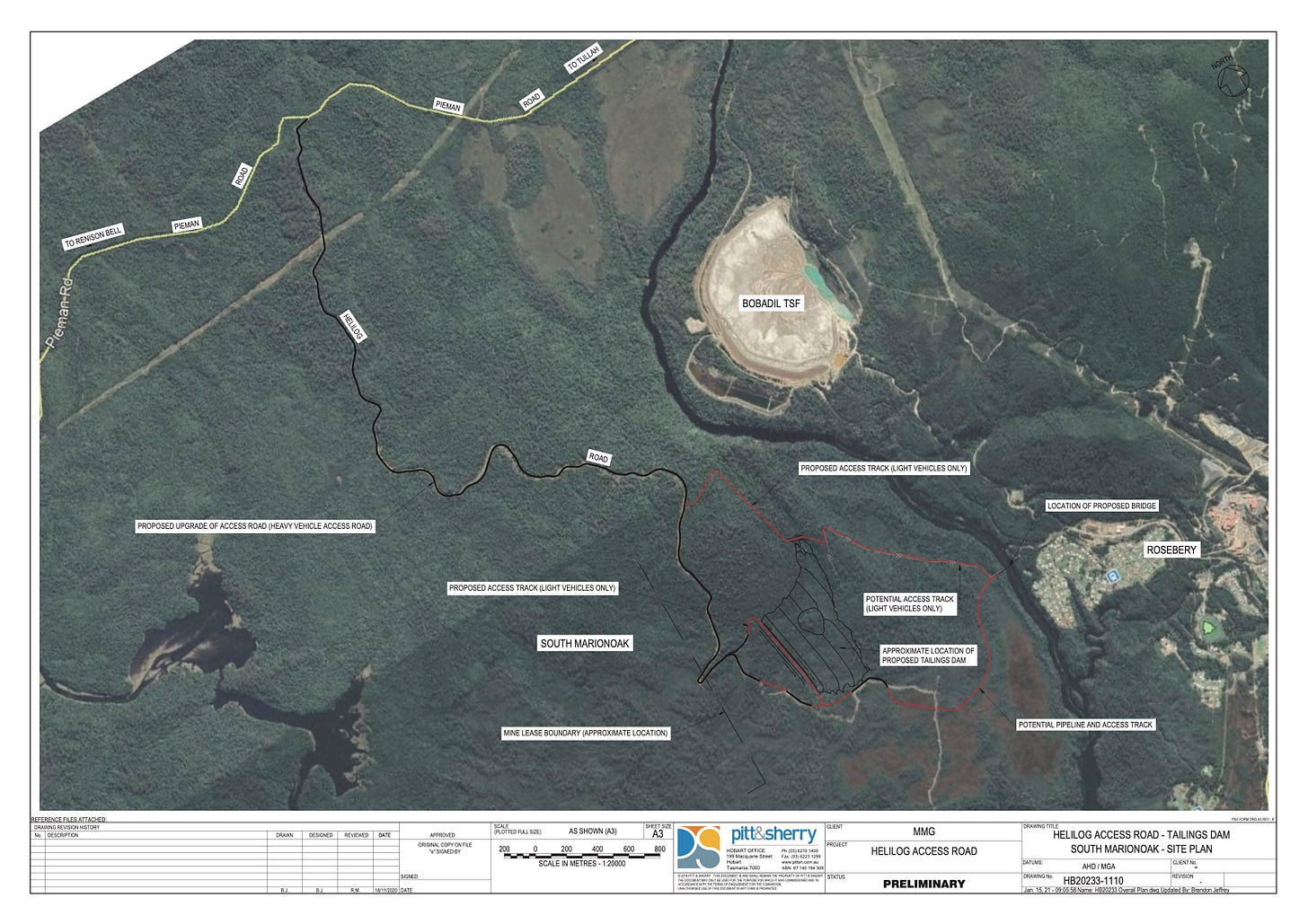

Direct Action

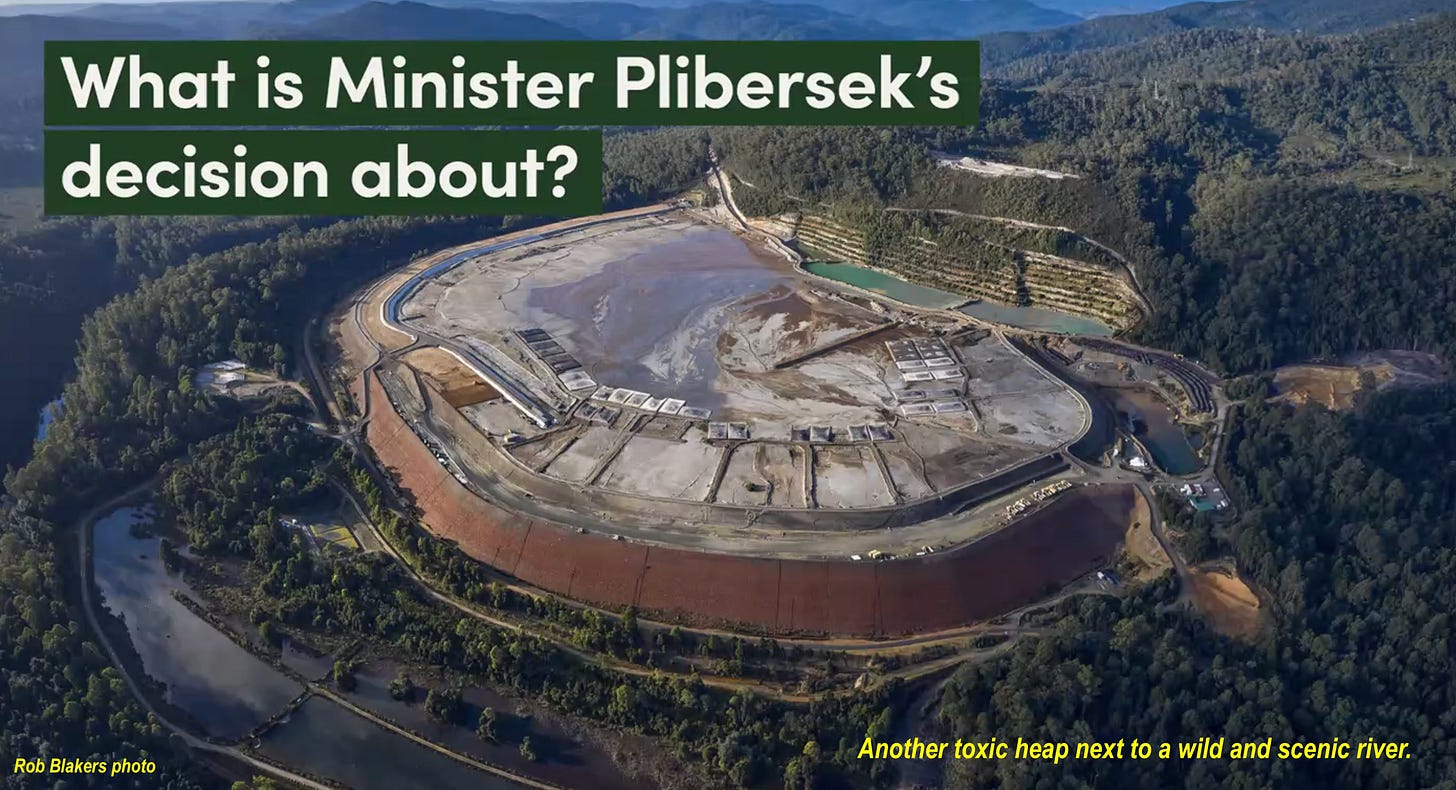

Widescale peaceful protest on many levels has been ongoing, but little has been done legislatively to change the status quo, so many see direct action as currently the only way to slow the final destruction of many of these areas. An imminent decision from the Environmental Minister looms over a proposal to dump 25 million cubic meters of toxic, acid-leaching mine tailings into a 140-hectare valley of 500-year-old myrtle and tall eucalypt forest in the Pieman area of takayna. This area of Crown Land has already seen countless trespass arrests of direct activists over the past several years preventing illegal and environmentally destructive work, along with ongoing legal challenges that have been delaying the proposed destruction of yet another unique Tasmanian ecosystem. Many are ready to directly act and help blockade the incursion into this wild landscape if the minister decides to allow the mining company to commence work here.

At some point, like so many brave activists who have already shown the way, reason demands that Tasmanian denizens who believe in its ecological future to stand in the way of senseless destruction taking place. For climbers like Paul and myself, it makes the most sense to climb and camp in the canopy—after all, the trees might be bulldozed the next day, and sitting in the way of its destruction seems a small price to pay for preserving its long life, even if just for a moment. And it is just truly beautiful camping in the canopy. Like the imaginative play of a traditional treehouse, it’s a place of adventure, solitude, a sometimes an act of solo rebellion (who hasn’t, if they were lucky enough as a kid to a treehouse nearby, find it the best place to “get away from it all”?). Bags are getting packed and ready for the expedition.

Appendix

Tasmanian Times Observations in 2021 (John Middendorf)

Forbes article on aerial protesting (Ari Schneider)

Portaledge protesting article (Joy Martin)

Activist Portaledge developments article in Gripped (David Smart)

Thanks to Scott Jordan, Rob Blakers, Steve Pearce, and Geoff Law for help with this article.

The natural world is the climber’s office. It’s here that we innovate we expand, and we learn from everything around us. Nature is not a part of us, but we are a part of it. Now is not the time to sit back, but to act.

I should mention, especially for climbers, that establishing weatherproof camps in the tall trees of Tasmania requires the most expert rigging and safety skills (BBF offers regular training camps). It's fully "heads-up" in climber talk in the trees, once I was in a strong gale and it is much more intense than the experience of a severe storm on rock, as the wind comes from all directions in a tree. Securing the ledge at frame level to the tree is essential. I have uncut footage of a couple nights in a wild storm here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NVjIq5Kszbc

And a short film I made back then: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=wkH9ZKQ8SBw

Another key moment in portaledge protesting (first cable logger): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M4SzXFIW5CU