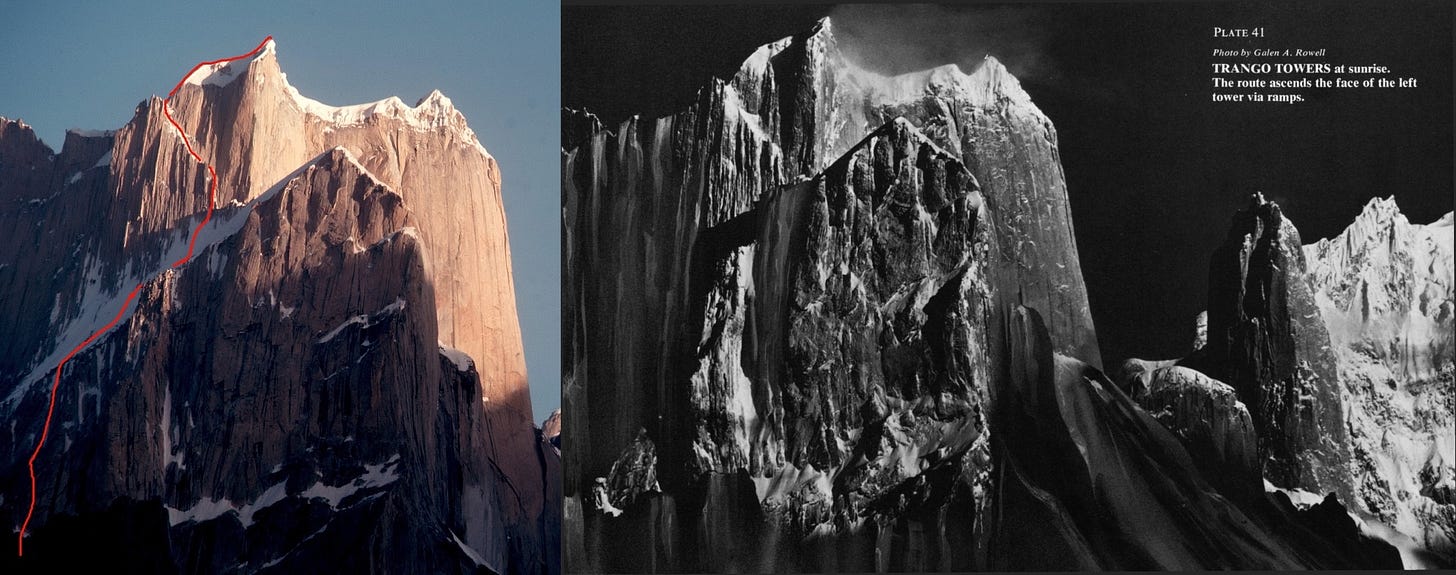

First ascent of Great Trango Tower (1977)

Trango History Series by John Middendorf

The first route on Great Trango Tower, then known as Middle Trango Tower, was climbed in 1977. Galen Rowell called it ‘Shipton’s Dream’, referencing the response of Eric Shipton, who died that year, when asked what he would have done differently in his climbing and mapping career: “I wouldn’t have spent as much time mucking about Mount Everest. I would have gone to lower peaks that could be climbed with a few classic tools by a few friends.”

Himalayan Climbing

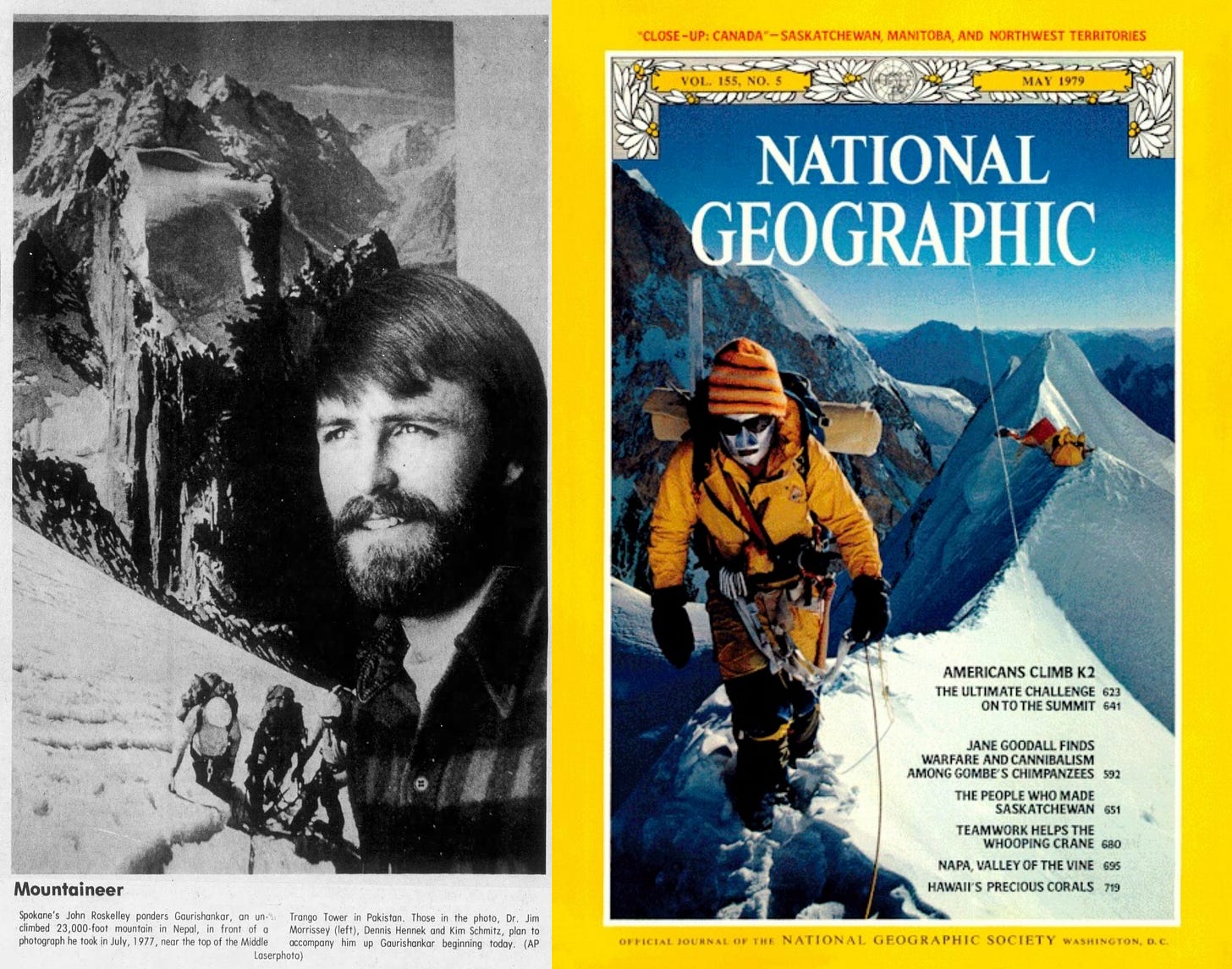

The expeditions to the 8000m peaks like Everest were generally huge affairs in the era, with leaders managing multiple teams partnering with high-altitude Sherpas. John Roskelley reflects on climbing the third ascent of Dhaulagiri (8167m) via the northeast ridge in 1973 with Nawang Samden and Lou Reichardt, a ‘quiet, introspective man’ and the sole survivor of the ‘Death of the Seven’ (AAJ, 1970), when on the same peak in four years prior half of his team perished in an avalanche: “I didn’t really get to know (Reichardt) despite months on the same team. In ten days of living in separate tents within twenty feet of each other in Camp III, we had talked only once or twice.” Objectives and strategies on peaks like these involved multiple teams working on different dangerous components of the ascent to get someone on top, which then becomes the success of the team.

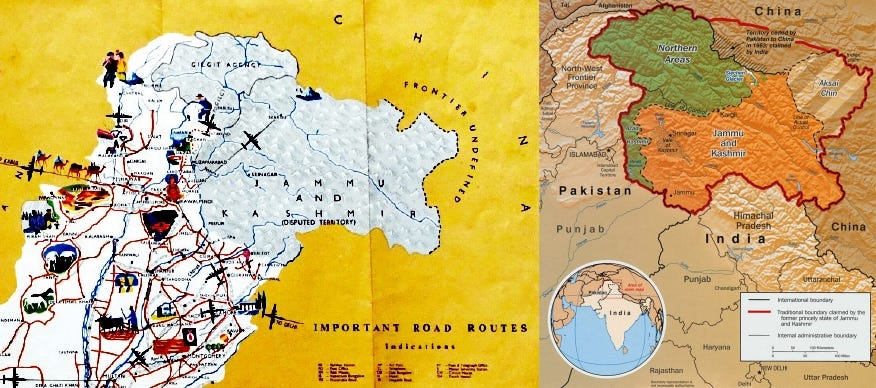

Karakoram Access

Mustagh Tower was first ascended by two routes in 1957 (British and French teams), and Masherbrum in 1960 (American/Pakistan team), but by 1963, most of the technical challenges of the Karakoram were closed to mountaineering as border conflicts between Pakistan, India, and China flared (footnote). As regions along the Baltoro batholith re-opened, an Austrian team in 1970 climbed K6 in the Hushe Valley, and initial forays on the steep walls along the Biafo Glacier began with an attempt on Baintha Brakk (the Ogre) in 1971. In 1974, Momin Hamid fell to his death during an attempt at Paiju, and Masherbrum La was traversed, but the rocky granite towers further along the Baltoro Glacier were among the last Karakoram peaks to open due to its access to Sia La, the pass to the Siachen glacier near the line of control between Pakistan and India.

footnote: On one of the last 1960s mountaineering expeditions to the Baltoro, on August 4, 1963 a team from Japan summited Baltoro Kangri (formerly Golden Throne). Professor Seihei Kato, leader; Dr. Hyoriki Watanabe, deputy leader; Sumio Shima, Keiko Fujimoto, Kiyoki Okada, Takeo Shibata, Shoji Seki, Masaru Kono, Matoo Yanagisawa, Naoyuki Morita, Yoshichika Takenouchi, Tokutaro Noguchi; and the Pakistani liaison officer, Captain M. Afsar Khan. 200 porters stocked basecamp and Camp II.

Tools

In the decade of the Baltoro’s closure, standards had risen, and as access increased, and in contrast to expeditions with dozens of personnel and hundreds of porters stocking basecamp, the idea emerged that small lightweight teams could climb even the giant alpine challenges in the Karakoram. Lighter-weight expedition clothing and shelter, improved ice and clean climbing tools, and increased skill simplified the trade-offs between the climb’s technical severity and natural hazards, as smaller teams could more efficiently dispatch dangerous ice couloirs, often found on the approaches to major features. New Karakoram challenges became envisioned as the new tools enabled faster vertical travel on ice and rock, expanding ideas of what was possible.

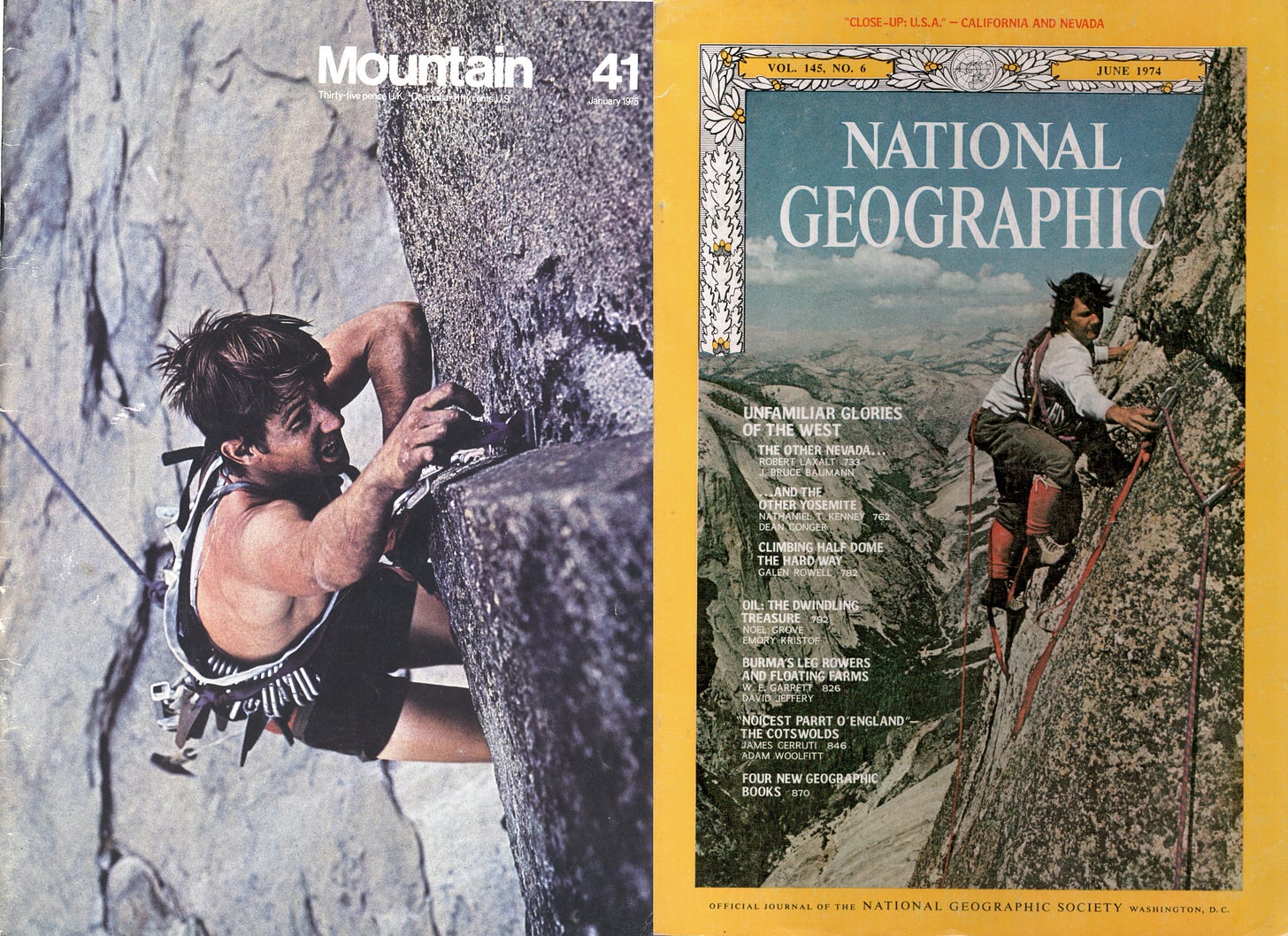

Yosemite Super-Alpinists

In the 1963 American Alpine Journal, Yvon Chouinard predicted that "Yosemite will, in the near future, be the training ground for a new generation of super-alpinists who will venture forth to the high mountains of the world and do the most esthetic and difficult walls on the face of the earth." James P. McCarthy, Layton Kor, Richard McCracken, and Royal Robbins immediately proved the prediction in 1963 with their ascent of the southeast wall of Mount Proboscis, "one of the most elegantly direct routes that one can hope to climb." (Jim McCarthy); in the decades that followed, Yosemite continued to foster super-alpinists who ventured forth, and it was in this spirit that the 1977 Great Trango team gathered.

Footnote: In the 1966 Alpine Journal (UK), Chouinard’s quote appears with a ‘merely’: “Yosemite Valley will in the near future be merely the training ground for a new generation of alpinists who will venture forth to the high mountains of the world to do the most aesthetic and difficult walls wherever they may be found.”

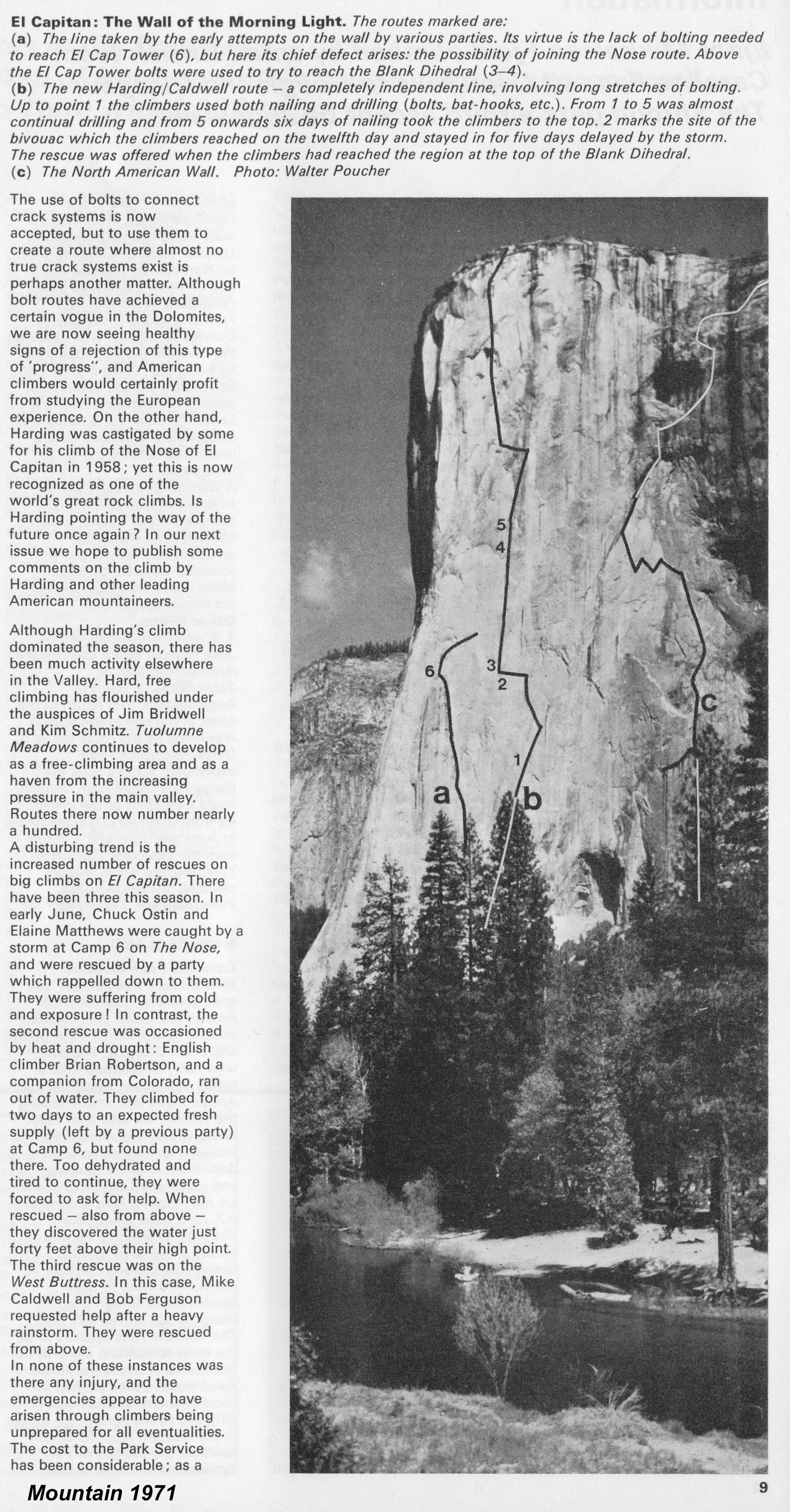

Dennis Hennek

The 1977 American Karakoram expedition was led by Dennis Hennek, who thrived in one of Yosemite’s interim periods, between the fading ‘Golden Age’ of the later 1960s and the well-known long hard and free climbing era of the early 1970s (when Hennek was venturing in the high mountains). In 1966, Hennek climbed a three-day first ascent on Sentinel with Ken Boche, quite a feat in the days of only pitons for protection and aid, and in 1968 the five-day second ascent of the North American Wall with Don Lauria, then considered one of the hardest bigwalls in the world. In 1971 and 1972, Hennek spent his summers among the rock walls of Baffin Island, climbing many Sentinel-sized bigwalls in arctic conditions in fast time with various partners. With Doug Scott, Paul Braithwaite, and Paul Nunn, they climbed the east pillar of Asgard and attempted the prize bigwall line envisioned on the imposing west wall of the north tower, which was later soloed by Charlie Porter in 1975. Hennek was also at the forefront of new clean technology with the first clean ascent of the northwest wall of Half Dome with Doug Robinson and Galen Rowell in 1973.

Hennek’s first trip to the Karakoram in 1975 (see sidebar) did not go as planned or hoped, but the experience flowed into the 1977 American Karakoram Expedition.

SIDEBAR: 1975 American Karakoram Expedition.

When Galen Rowell wrote in Climbing Magazine in 1979, “To date, only a very few Americans had taken technical climbing in the Himalaya. In 1977 I was lucky to be a member of the only expedition from America that had successfully broken the trend. We climbed the virgin Great Trango Tower in the Karakoram Himalaya,” he was glossing over an expedition organised by Dennis Hennek in 1975. This included an all-star cast of climbers including Don Lauria, Yvon Chouinard, Doug Tompkins, George Lowe, and Micheal Covington, all among the best alpinists and bigwall climbers of the era. A film crew also accompanied the team. In 2017, Don Lauria wrote one of the best Supertopo trip reports of the 1975 expedition, which, unlike the famous First California Funhog Expedition to Patagonia with several of the same team who climbed Fitzroy in 1968, the trip sounds like a very trying expedition for all involved, with more than the usual spirit-destroying trip delays due to paperwork in Rawalpindi, stomach problems, transport and porter challenges.

The plan was to set up their main base camp at Urdukas, with a grand view of the Baltoro Cathedrals. From there, they would scout and climb objectives on the other side of the Baltoro Glacier and set up advanced camps. Without a specific objective, the team split into smaller groups with some successes and frustrating failures, often due to severe weather or sickness. After summiting Lobsang Peak (6225m) at 2:45pm, Hennek, Lauria, and Covington decided on the summit, “Such a nice day we decided to stay,” and Lauria wrote of the sunset scene: “Mustagh Tower, Pyramid Peak, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum IV, Chogalisa, Nameless Tower, Masherbrum – alpenglow like no one ever sees. Also noted some dark ominous clouds drifting in from the west – not a good sign.” Indeed, in the middle of that Karakoram night, exposed with no tent, at high-altitude on a steep peak, a storm moved in, resulting in an epic descent the next day back to Mustagh Meadows, their advanced camp, racing “the impending and certain avalanches that would fill our tracks”. The trip might not have extended technical climbing in the Himalaya, as Rowell noted, but the experience provided valuable information about alpinism in the Karakoram and a clearer strategy for climbing objectives in the future.

END SIDEBAR

Kim Schmitz, Galen Rowell, John Roskelley

The other super-alpinists of the 1977 American Karakoram Expedition team were Kim Schmitz, Galen Rowell, and John Roskelley, with a vast depth of experience; stories of their amazing climbing careers fill books. Schmitz was one of the fastest bigwall climbers of the era, having climbed a new route on El Capitan in three days in 1971 with Jim Bridwell (amidst media circuses focused on the longest time ever spent on El Capitan), and was known for his fearlessness and as a dancer on hard alpine climbs in North and South America. Galen Rowell needs no introduction, well-known for his mountain photography; in the 1970s he was among the leading Sierras climbers, honed on hard vertical alpine rock and ice, experience on K2, as well as an extensive record of technical bigwall climbs in Yosemite, Bugaboos, and other North American bigwalls.

The team had plenty of bigwall and alpine climbing experience but Roskelley perhaps had the widest-ranging ‘training grounds’ on the testpiece alpine and ice climbs. For Roskelley, Yosemite was not as much his primary training ground but perhaps more his exam room. During his ‘brief stays’ in Yosemite, including a full spring to fall season in 1971, he consistently made noteworthy bigwall ascents, and set records unmatched for years, including a three-day third ascent of the North American Wall with Mead Hargis (footnote). Also on the Great Trango team were two doctors: Jim Morrissey, a member of the 1969 and 1973 American Dhauligiri Expeditions, and Lucian Buscaglia, who helped fund the expedition.

Footnote: In the mid-1980s, Mead Hargis was a Park Ranger, and worked with our Camp 4 climber rescue team on many search and rescues. We often wondered at how he had climbed the North American Wall in the pre-cam days (1971) in three days (two point five days more precisely) with Roskelley. Mead always just said, humbly, ‘I guess we were fast.’ Note: In his collection of vignettes with morals, Stories Off The Wall (Mountaineers, 1993), Roskelley does not relate the story of climbing Great Trango Tower (but covers Uli Biaho in depth—next chapter).

The first ascent of Great Trango Tower

With the team’s vast experience, it was time to merge their skills to summit the unclimbed high-altitude Great Trango Tower. The team arrived in Rawalpindi during one of Pakistan’s frequent military coups—the Pakistan army had recently deposed Prime Minister Bhutto and declared martial law. Remarkably, the team was able to fly to Skardu after a speedy week of expedition paperwork, and seven days later, with the help of twenty porters hired in Dasso, they established basecamp on the Trango Glacier near the junction of the Baltoro Glacier. Galen describes their basecamp as a sandy moat with running water and “countless wild roses, fireweed, buttercups, and the tracks of ibex, mountain sheep, brown bear, fox and snow leopard.”

The climb, day 1

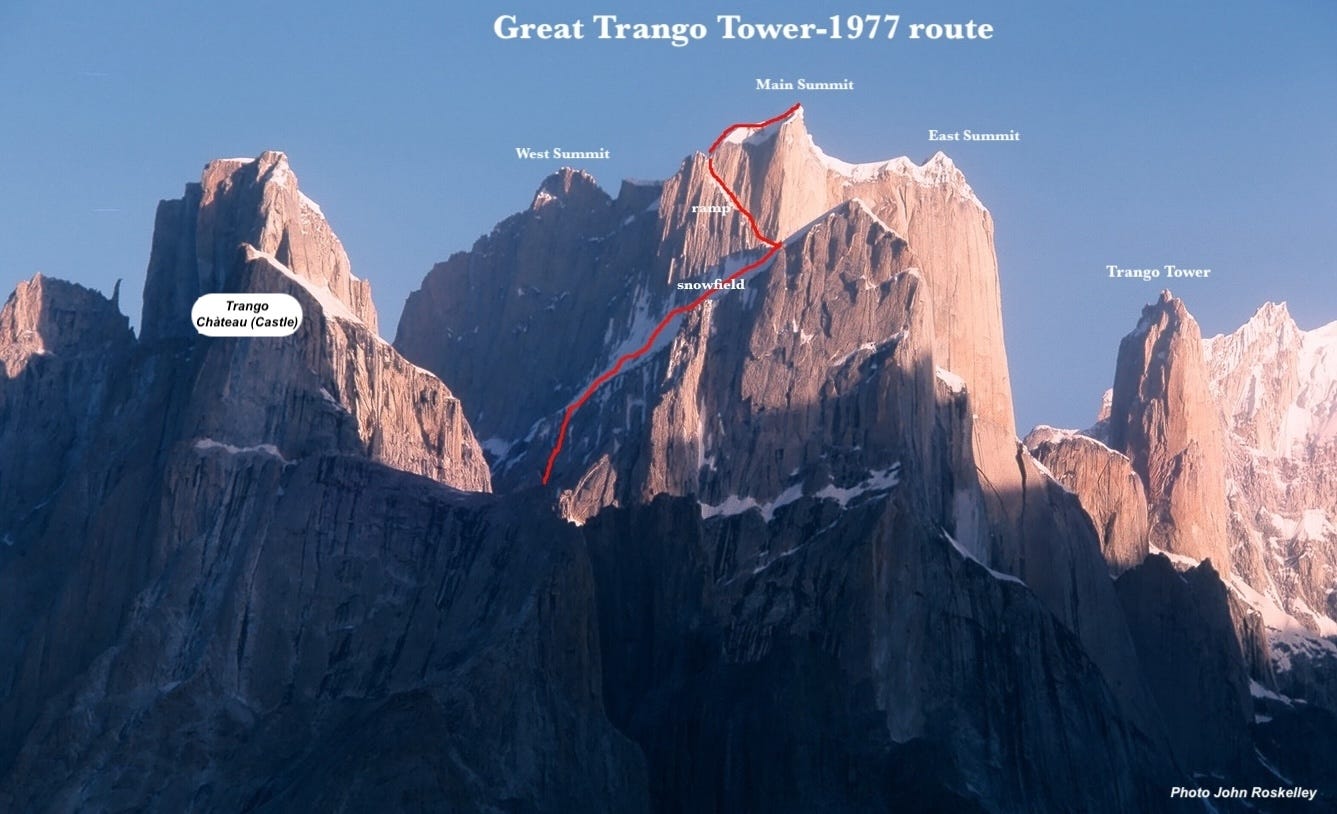

After waiting out a few days of storms and avalanches, the team began their ascent on July 19. A major objective hazard of their line on Great Trango is a huge hanging snowfield that forms the south side of the Pulpit. The snowfield frequently avalanches, funnelling debris into a steep couloir below the notch between Great Trango and the lower peak to the south (Trango Château). Starting before dawn, soloing with four ropes in their heavy packs, the team started up this funnel. After four hours of rapid climbing and ever-aware of the snowfield’s afternoon avalanche pattern, Galen, John, Kim and Dennis reached the notch at noon. Jim Morrissey, following behind more slowly, was in the gulley when the snowfield avalanched, and was nearly swept away with Lou Buscaglia but soon rejoined the team, and set up their first bivouac in the notch (footnote).

Footnote: In Baltoro,Montagnes de Lumière (mountains of light), Louis Audoubert describes this moment (translated from French): “On July. 19, as soon as the good weather returns, they begin with the prospect of alpine or semi-alpine style climbing. It is with great apprehension that they pack their bags and head out into the hallway. Around noon, they took shelter of the large bastion and began to prepare the bivouac. They believe that the time of choice has come: not everyone can climb, but who will give up? Should we eliminate the two doctors: Lou Buscaglia and James Morrissey? But they are precisely the ones who participated most financially in the expedition... However, they have less experience... They are at this point in their procrastination, when the much feared avalanche is triggered. However, Buscaglia and Schmitz are still going up in the corridor. The waterfall of blocks rushes into the corridor and it is by a miracle that the rope party avoids it. Faced with these dangers, Buscaglia withdrew. They will therefore continue with five, Buscaglia will be waiting for them in the tent.” note: both Hennek and Rowell report it was Buscaglia and Morrissey who were still in the gulley when the snowfield avalanched.

The climb, day 2

From their camp at the notch, the next morning Galen and Kim continued up steep rock to the lower part of the snowfield which involved difficult free climbing and some aid, trailing ropes for Dennis, John and Jim, who followed with the food and bivouac equipment (Lou stayed remained the notch camp with the team’s only tent). In repacking loads at the notch, somehow much of the food got left behind. Once on the snowfield, all five followed a fresh avalanche tracks up the snowfield, and at the base of a steep ridge that led to the summit, chopped out a bivouac platform for their second night.

The climb, day 3

The upper part of the route finally visible, on the third day, the team awoke to a clear, sub-freezing day—perfect conditions for the final climb. John and Dennis set off, trailing ropes for Kim, Galen, and Jim. Dennis recalls, “This section offered some of the best climbing of the entire route. Orange granite as solid as any I have ever seen, formed the gradually steepening walls of the chimney. Using nuts and (ice) screws for protection, we cramponed up the chimney’s back. In the upper section, mixed rock and crampon techniques brought us back on the ridge again. The ridge disappeared gradually into a gulley that led to a corniced notch below the summit. John led the last roped pitch above the notch that ended in some boulders below a snow plateau leading to the summit. By 4:30 all five of us stood on the summit. The afternoon was warm and clear, with an unobstructed unforgettable view in all directions. We all agreed that there could be no better view of the Baltoro Karakakorm” (Hennek, 1978 AAJ).

The team descended in two days, “bursting with joy inside”, and once safely back to basecamp, “renewed their contacts with running water, living things, level ground, and the trail homeward.” (Rowell, Climbing 53). As Rowell noted, the first ascent of the Great Trango Tower might not have raised the “standards of height or difficulty in Himalayan climbing,” but it merged the full range of climbing and alpinism disciplines, and the elite teamwork for their three-day ascent led the way for future small-team super-alpinism on the rocky challenges of the Baltoro. Hennek sums up in the 1978 American Alpine Journal, “We proved to ourselves that a small, well-organized party can be successful in the Himalaya.”

Postscript/reference

(notes on post-GT climbs and guiding tk)

APPENDIX more 1970s bigwalls:

What a great compilation of primary and other sources, John! At the breakfast table here in Boulder, Colorado, reading this I was on the other side of the world. Super job!