Next for Volume 3 (aluminum carabiners, nylon ropes)

Tools for the Wild Vertical, Volume 2 finale

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Volume 3 will cover global developments of climbing tools and techniques, beginning in the 1940s and 1950s.

Developments during WW2 (brief overview)

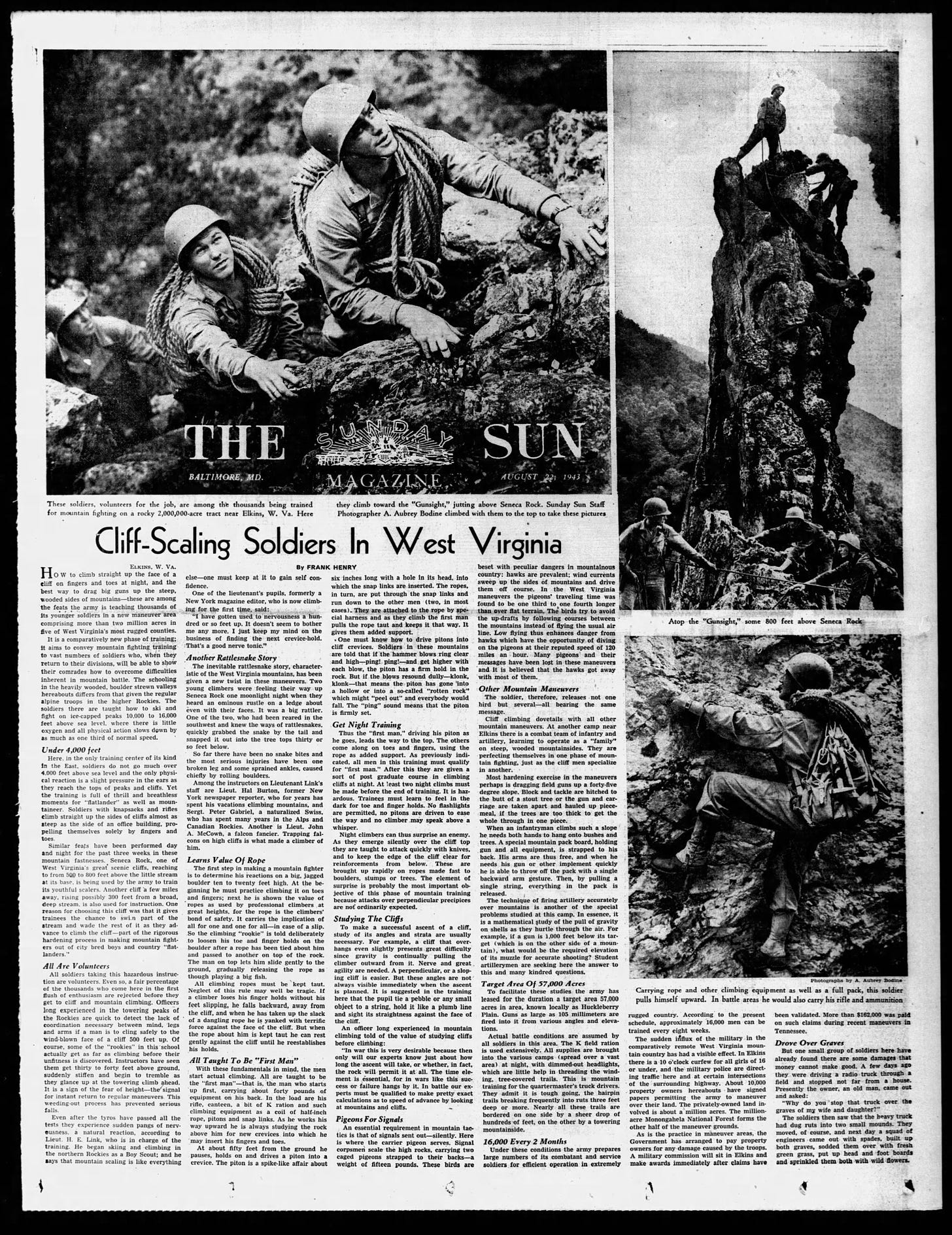

As war expanded in Europe, in December 1940 the American Alpine Club established the Defence Committee, with the goal of “supplying the Army with information concerning equipment to be used in mountainous regions.” The initial crew was chaired by Walter Wood and included Richard Leonard, Kenneth Henderson, Charles Houston, and Bestor Robinson. With military funding and inventive climbers, mountaineering and survival equipment advanced considerably in the period between 1940-1944, leading to improved outdoor gear made for arctic conditions, ski gear, and other camping equipment.

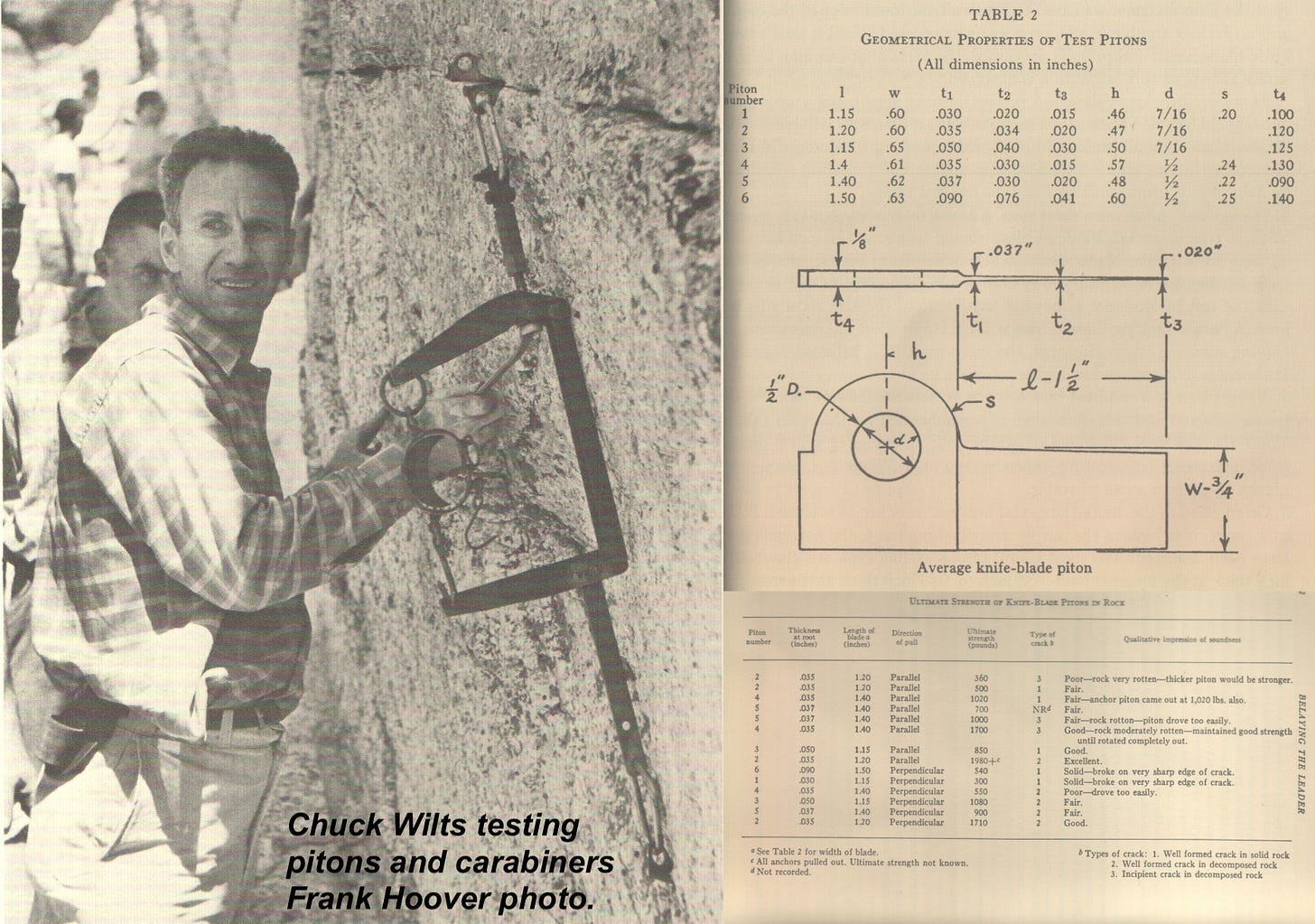

Pitons

A selection of pitons, including some of the first angle pitons (with ring) were developed for the army with the help of The Mountaineers’ Exchange in San Francisco (footnote) and manufactured by the Ames Baldwin and Wyoming Co., in Parkersburg, West Virginia. During trainings in 1943-1944, thousands of army pitons were hammered into the cliffs of nearby Seneca Rocks. As a typical pack carried by mountain troops could weigh over 35kg, designers strove to make additional climbing equipment as light and functional as possible.

Footnote: not much is known about the Mountaineer’s Exchange in San Francisco, cited in the Quartermaster Equipment for Special Forces, by Thomas M. Pitkin, Office of the Quartermaster General, 1944.

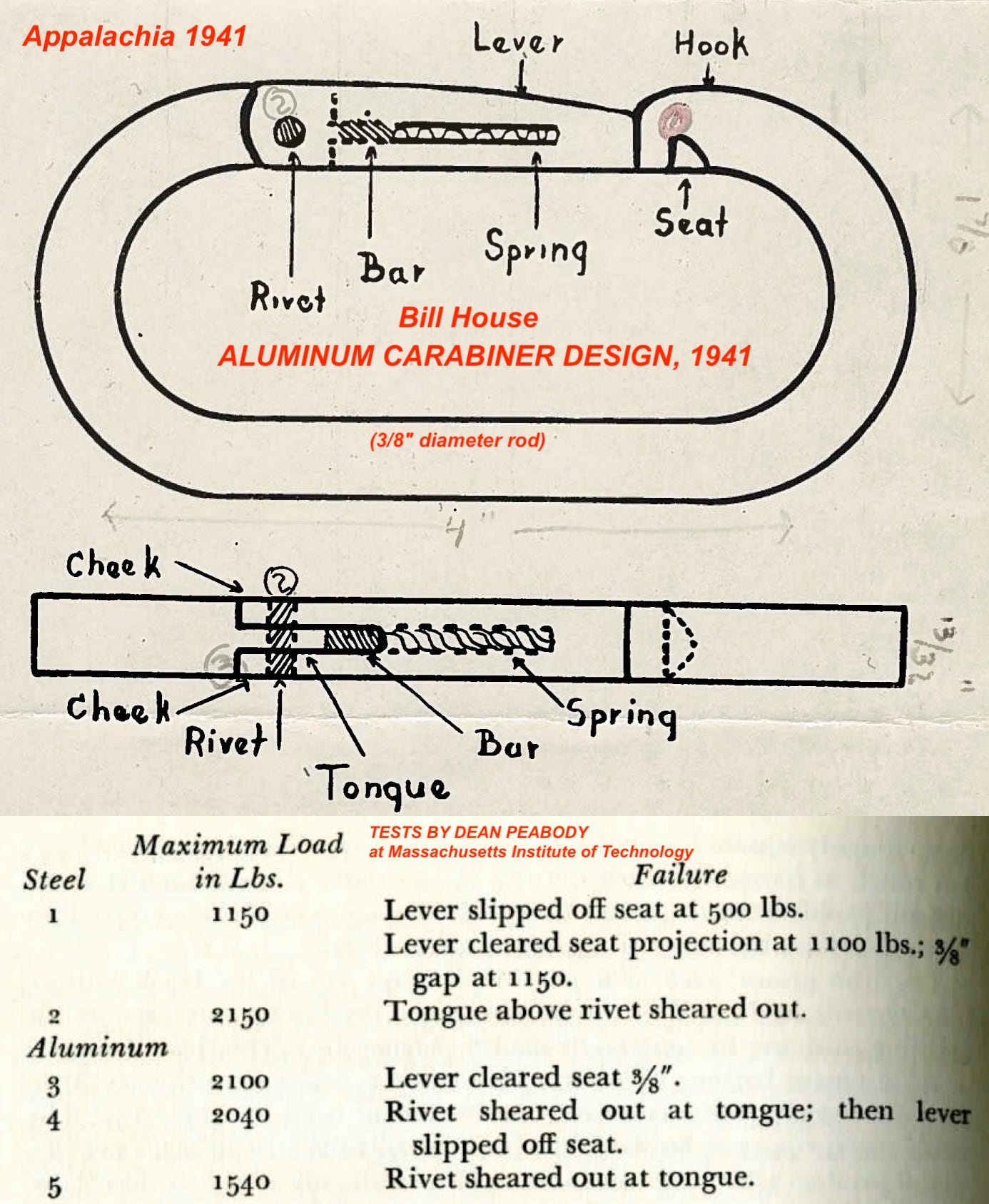

Carabiners

Bill House became head of the Army’s Quartermaster General Mountain Unit, responsible for determining mountaineering equipment specifications. In 1941 he began working with the Aluminum Company of America to develop new light and strong carabiners (then still called ‘snap-links’ or karabiners—Pierre Allain in France had been developing aluminum carabiners prior to the war, but it wasn’t until the later 1940s that aluminum carabiners became commercially available). House had begun with the standard toothed gate (‘hook and seat’) design, but by 1943 the Army carabiners had evolved to a pinned gate design, which became the standard for most aluminum carabiners for the next four decades.

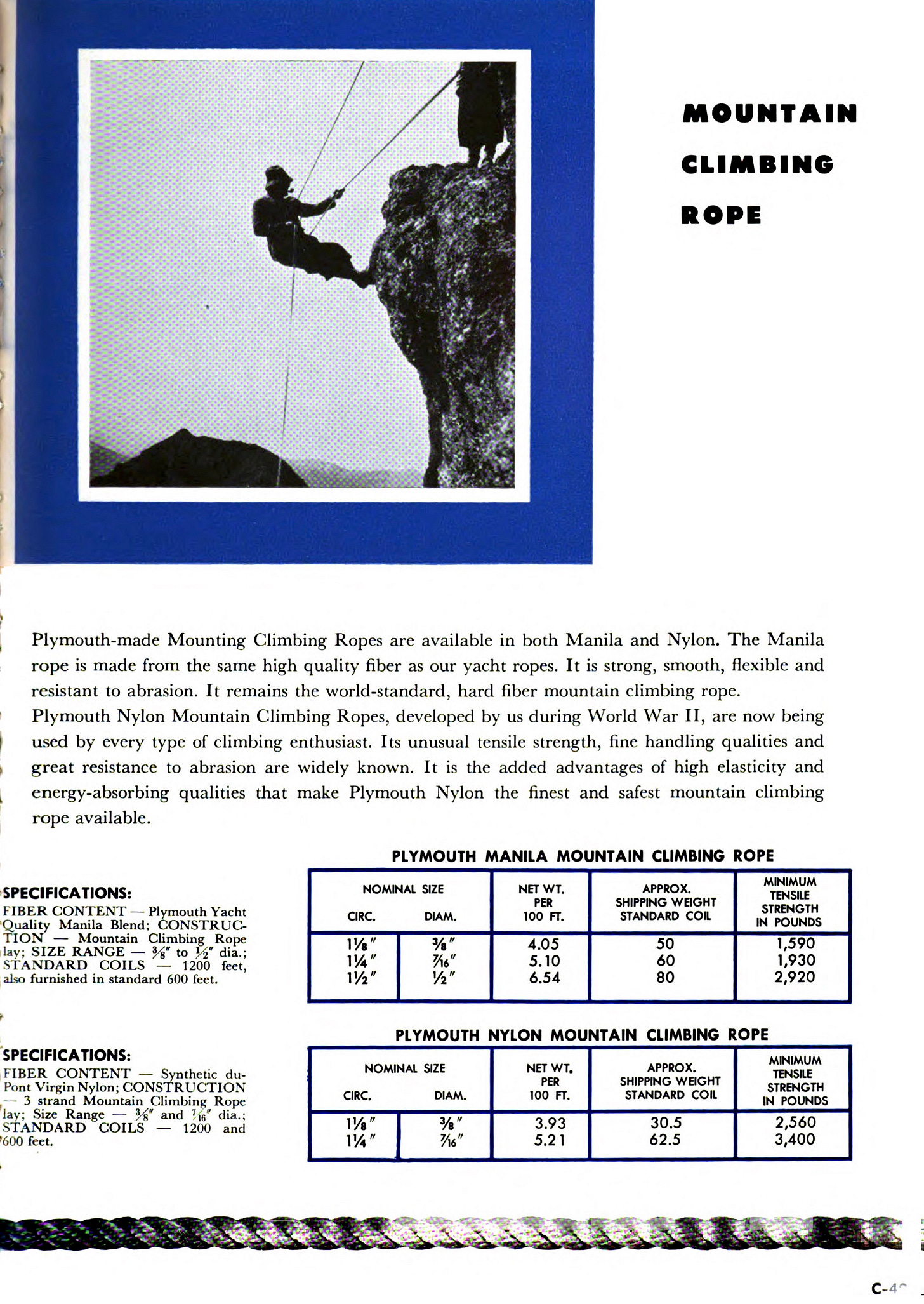

Nylon Ropes

Richard Leonard, meanwhile, as the leading expert in rope dynamics, became executive officer of the Quartermaster General's Special Forces equipment unit, and working with the Plymouth Cordage Company in Massachusetts developed and standardized the first 7/16” diameter, 120’ long, 3-ply nylon climbing ropes (weight: 6.5lbs, strength: 3400 lbs). Leonard worked with the engineer Arnold Wexler (1918-1997), working at the National Bureau of Standards in Washington D.C., who developed a comprehensive theoretical analysis of the forces involved in climbing falls with the new, high-elongation nylon ropes (thus, low-impact), and tested his theories with ‘Oscar’, his 68kg. dummy, at Carderock near Washington D.C. Nylon ropes improved handling and did not absorb as much water in wet conditions as did the natural fiber ropes (though many still preferred the natural fiber ropes because they were low stretch—those who were not doing much falling, in other words, perhaps using the rope more like a lasso or as a way to hoist your second up).

Bill House describes Leonard’s work on ropes in 1946 ‘Special War Number’ American Alpine Journal, “The almost incredible performance of some of the synthetic fibers suggested an investigation there. Under the able direction of Richard Leonard work was undertaken in cooperation with the Plymouth Cordage Company, and tests were made of many different types, consistencies and lays of nylon rope. With no exceptions the final choice of medium lay bright nylon was found to be superior to the highest grades of Manila. Chief and foremost was its great resistance to shock. It was found to absorb over three times the shock loading as the same weight of Manila. As an example, the best grades of Manila could be stretched only to approximately 13% of their length before breakage, whereas the nylon rope would stretch over 39%. Use of this rope in army rock climbing schools, where it received very heavy use, justified the confidence placed in it, and at the present time only high price should keep all mountaineers from using it.”

Plymouth was to later commercialize, using gold dye, the famous Goldline climbing ropes with improved strength (4850lbs. for 7/16” diameter), which became the standard American climbing rope for the next three decades. British Ropes Limited created the Viking nylon ropes in the UK, and a number of European brands also began manufacturing a variety of nylon ropes. The 3-ply, medium lay carried over from the manila design, remained the standard until the increased availability of reliable kernmantle ropes in the 1960s.

Post War

In Volume 3, we’ll examine more nuances of the evolution of climbing tools and technology, that parallel the well-known climbs which pushed new boundaries and amazed everyone, including often the participants themselves. As North America prospered, Europe rose like a phoenix from the ashes of war, a global network of mountaineering organizations bloomed, and so did the climbing standards in the periods to follow, along with the rapid evolution of the stronger, lighter, and more versatile climbing tools made possible with advancing technologies. The notion of what was considered possible on the wild vertical became a global phenomenon, and we will zero in on the highly specialized kit required for the biggest rock challenges.

Other topics

We’ll also try to decipher various definitions of climbing itself as it evolved in different regions. For example, consider these two mentions of climbing styles in the same journal in the same year:

Balance Climbing: “Since layback piton-pounding proved too difficult, Soler drove in six pitons for direct aid, skillfully edging on top of the one he had just placed in order to drive the next one. This maneuver whereby each piton was used first as a handhold, then as a foothold, without a rope sling, was a beautiful example of balance climbing. The 23rd piton, placed in a horizontal side crack in the left-hand overhanging column, permitted a short traverse and rétablissement (footnote) to its sloping, splintered top-the first belay point on the climb. After the other climbers had "prusiked" up to this platform, three more pitons were used before the party reached the big ledge at the N. end, from which an easy scramble led to the summit. During the 9½-hour climb, 26 pitons (24 of them angle pitons) had been used. The first pitch of what is now officially known as the Soler Route was belayed through pitons from the bottom during a 240-ft. lead!” (A.C. Lembeck, A New Route on Devils Tower, Wyoming, 1952 AAJ)

footnote: rétablissement is a French word for reestablishing, here a named maneuver.

Climbing Free: “So we started out. The extremely difficult part begins with a long piton traverse to the left, some 100 meters above the base. Emilio climbed most of that pitch free-hanging by pitons and little holds, not using the rope for pull at all. He put in very few karabiners, thus making it necessary for me to climb free, too. I found my way to a piton that he had used for a belay. As I removed the karabiner, I lost my grip on the piton, my only hold, and fell. For what seemed an endless time, I became a terrifying pendulum, swinging in space. Emilio held me with the help of some pitons. When I finally stopped moving, I found myself several feet away from the rock. It took much effort and time to swing back to the rock, anchor myself, and work my way back. This incident ended the attempt and the season. (Hans Kraus, Summer in the Dolomites, 1952 AAJ).

Innovation origins by small shop producers

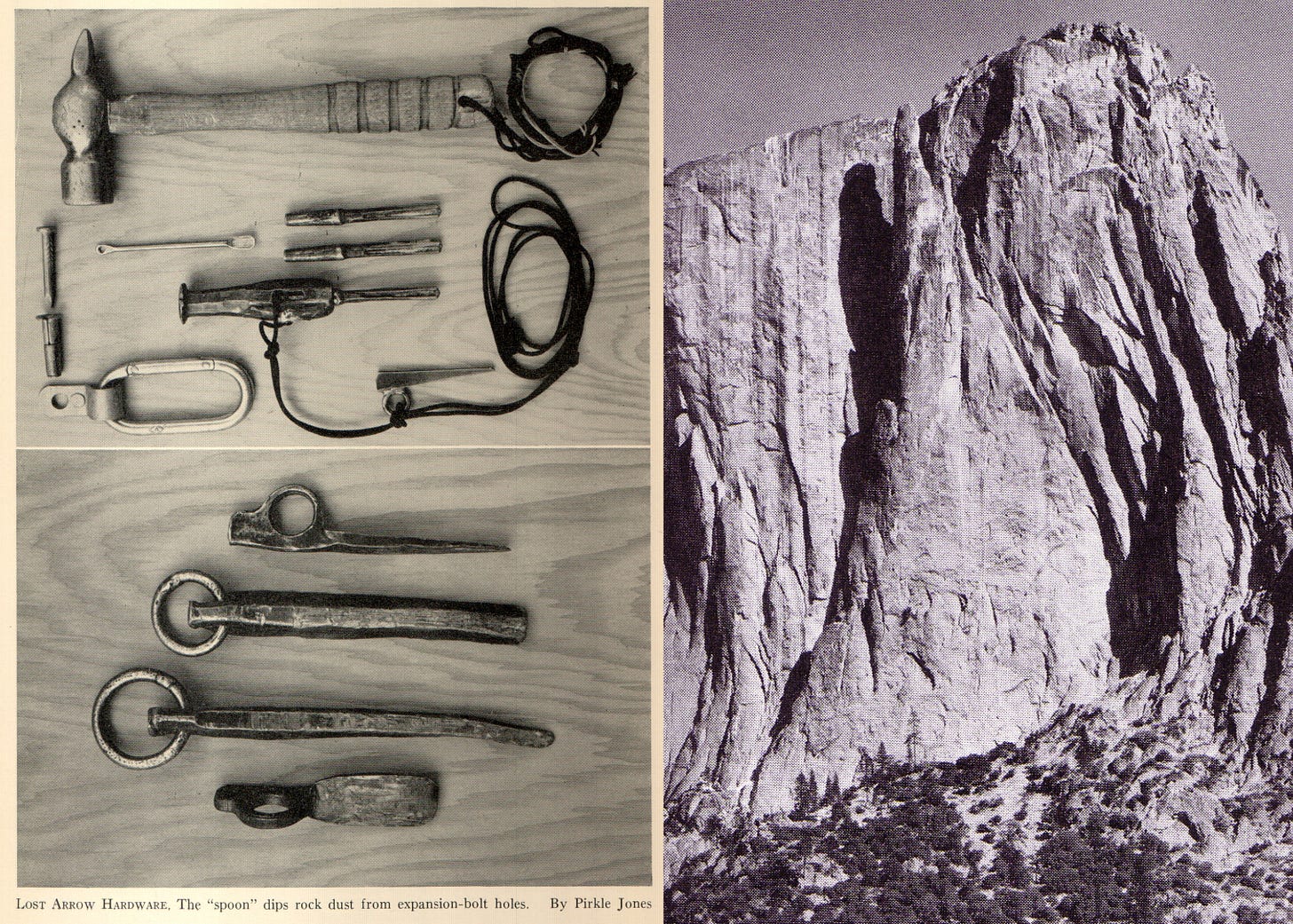

We will also look at the home shop innovation of the 1950s USA and also consider the engineering and sources of steel for some earlier European pitons as well as the famous chrome vanadium used for Salathe’s original Lost Arrows, and the chrome-molybdenum piton era of the mid-1950s.

Two mysteries outstanding:

Early complete bigwall ‘kit’, 1947:

As always thanks for reading, and comments are especially appreciated, as I hope to have a few more for my blurbs on the back of Volume 2, which should be finished shortly!

Thanks so much for all your research and hard work, John. I'm fairly new to climbing but am obviously a climbing tragic/nerd in the making because I'm finding your content extremely interesting.

I'm shocked at how pitiful my collection(s) of military/medical books look next to your climbing ones. I have much more nerding out to do!!

Can't wait for volume two to be ready for printing!!

Kind regards,

Nick.