1950s USA Climbing Gear notes V2

Mechanical Advantage series by John Middendorf for Volume 3

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

REVIEW (see Volume 1)

Prior to 1906: pitons were used sporadically, usually a spike placed for a hand or foothold in the same realm as the many via ferratas of the period. Also acceptable as a rappel anchor by most mountaineers.

1906-1914: Eastern Alp climbers take piton-protected free climbing to new heights, led by bold and naturally skilled practitioners like Tita Piaz. Engineered climbing really begins, and the design of the most lightweight, functional tools begins.

Post WWI: European piton-protected climbing really takes off with spectacular new rock routes, and about a decade later, a similar boom erupts in North America.

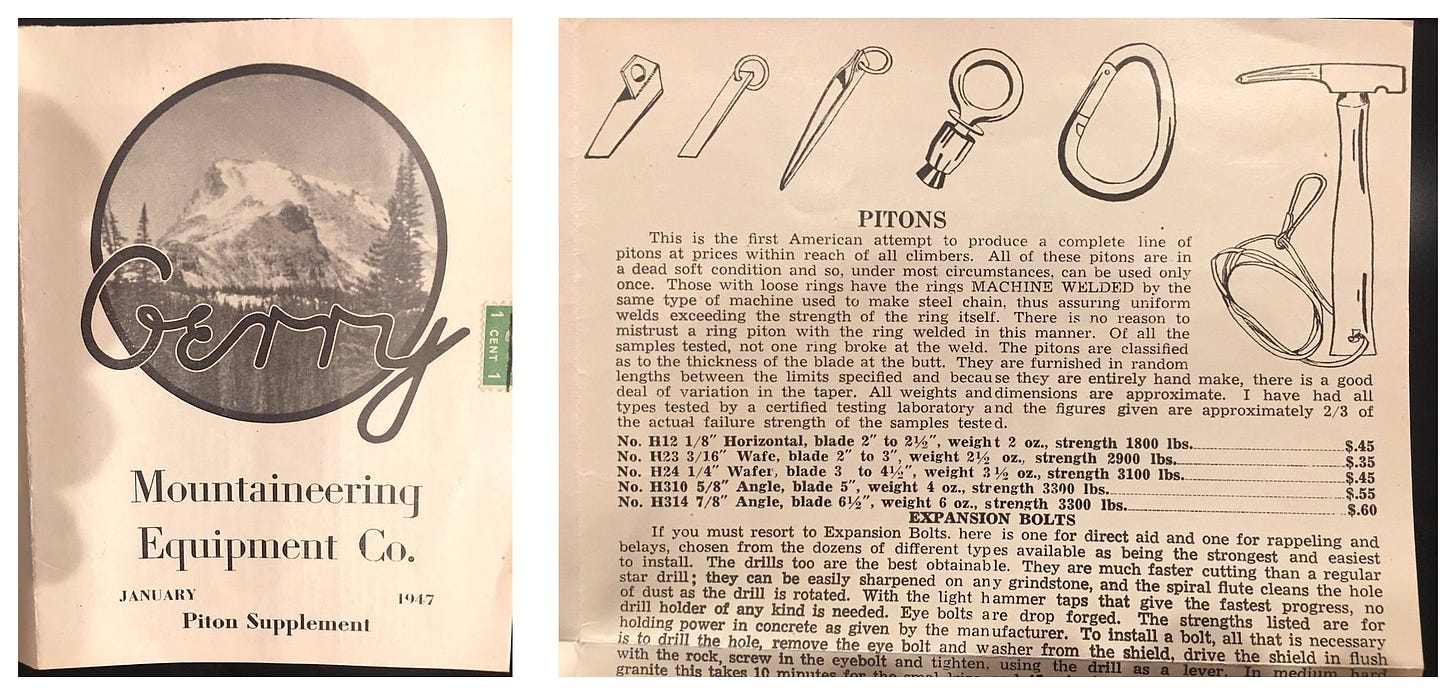

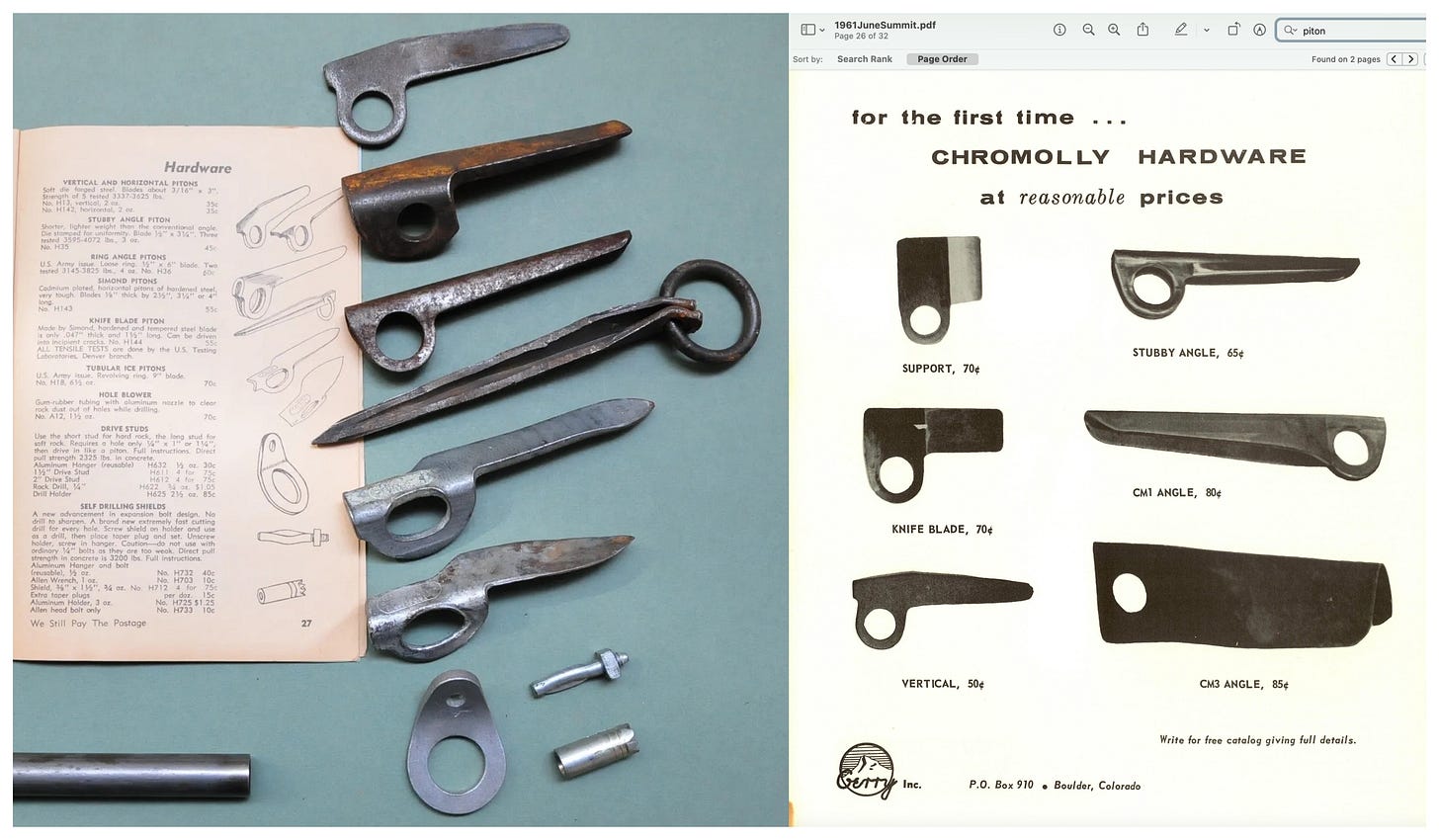

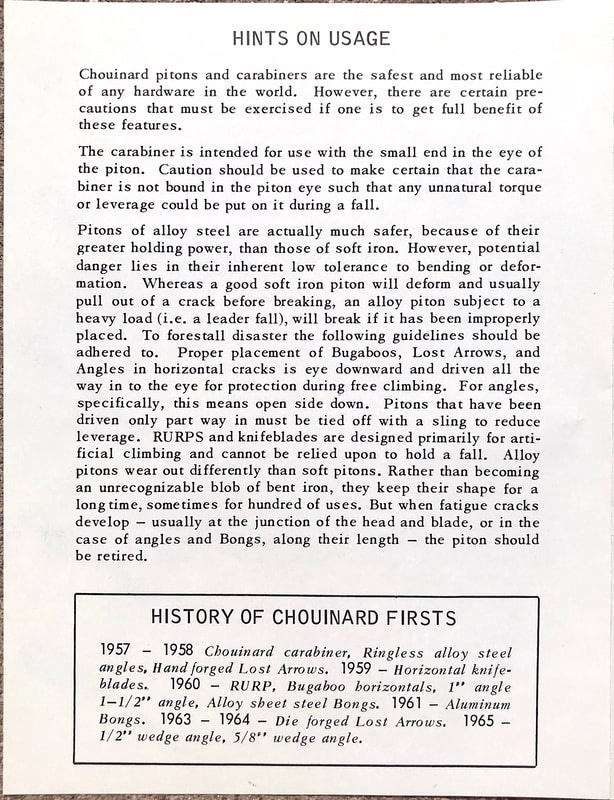

Regarding steel pitons: In the later 1920s, American climbing and piton production began a steady evolution, piggybacking on new developments in the USA steel industry, leading to the high alloy steel pitons of the 1950s which in turn led to opening the doors of Yosemite’s big walls, and to visionary big wall climbing elsewhere on the planet. The well-known as the “Golden Age” of Yosemite climbing, noted by historian climber Steve Roper as the quarter-century between 1947-1971, when many huge technical big wall routes in Yosemite were first climbed, was an accumulation of many new tools and techniques merging at the time. There are many great online collections of mostly post-WWII pitons and other mainstream equipment of this period, but the exact chronology of hardware needs refinement. In the age prior to the widespread use of clean climbing protection, piton craft was an essential art for hard rock climbs; this post is an attempt to add further detail in the chronology between the 1940s and 1960s—also see this post covering the major brands of climbing gear available in 1964.

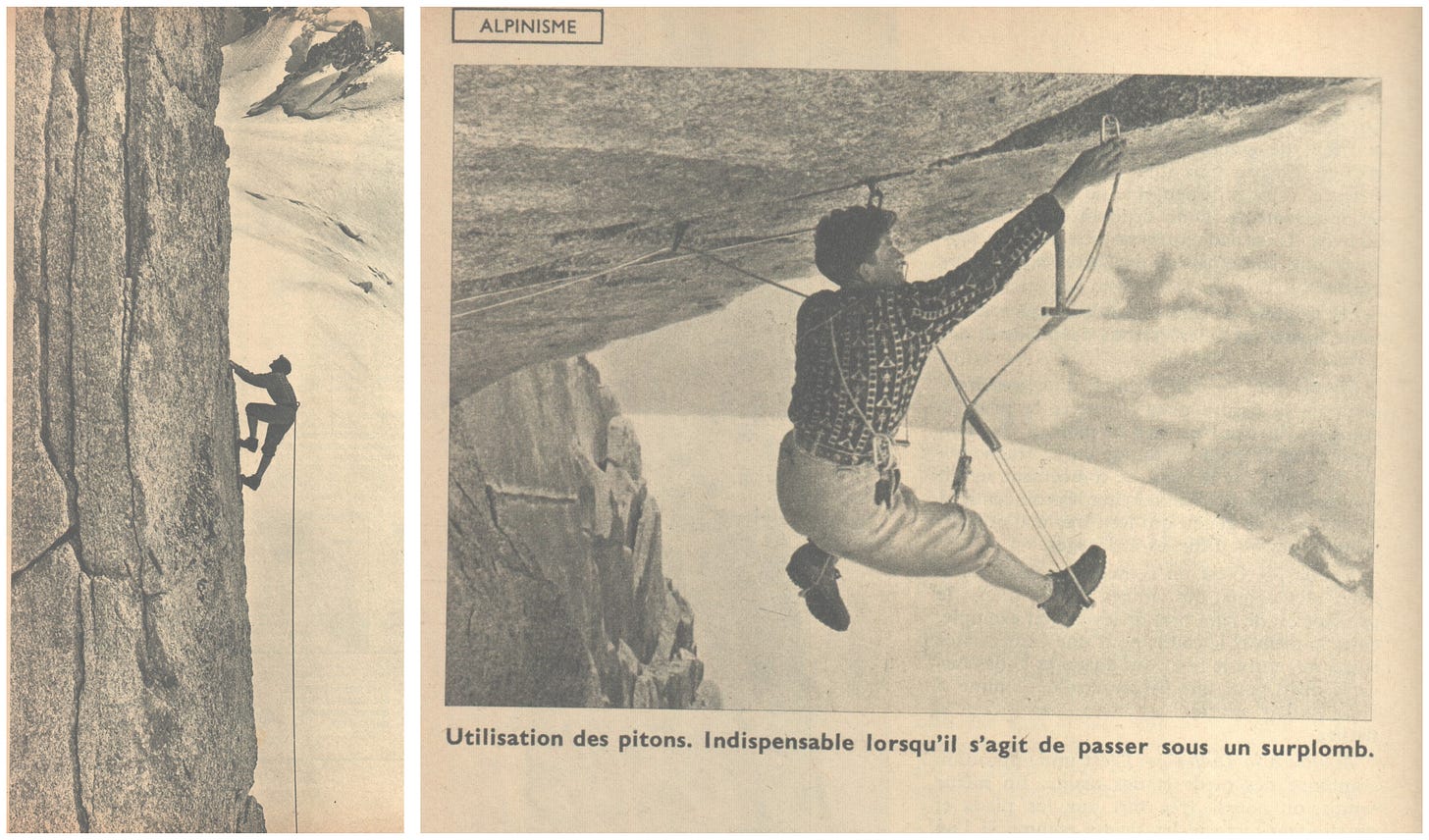

The 1950s

In Europe in the 1950s, climbing had become a mainstream sport, and heroes appeared regularly on the covers of national magazines. The legends of climbers needing to forge their own pitons prior to a first ascent had long passed, and there were a number of manufacturers competing for market share by offering wider availability of relatively inexpensive, mild steel pitons of varied designs. Pitons were mostly the “vertical” and “horizontal” designs developed in the 1910s, now with dozens of design variants and thicknesses, though the largest pitons on offer were suitable for only about the size of a fingertip—anything bigger was thought climbable without protection, though wood wedges (“coins de bois”) were sometimes used for larger cracks if aid was required. And of course, bolts were becoming more common (bolting technology will be covered in a separate post).

Though most European mountaineering equipment in the 1950s was mass-produced as mature products, in the 1950s USA, a blacksmith-driven period of innovation was about to begin.

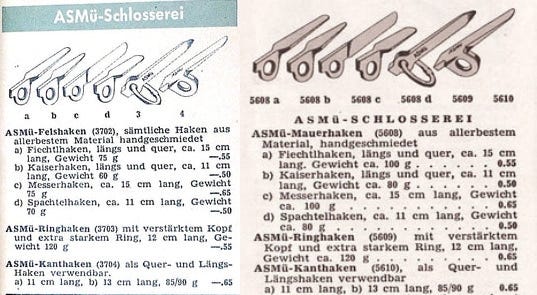

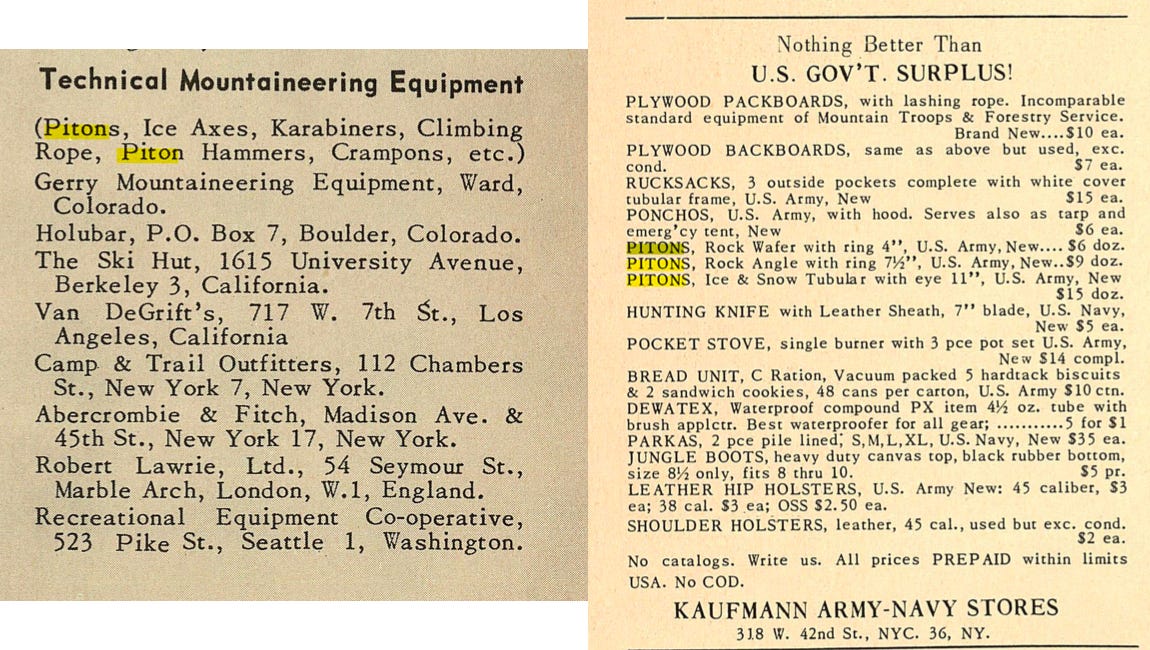

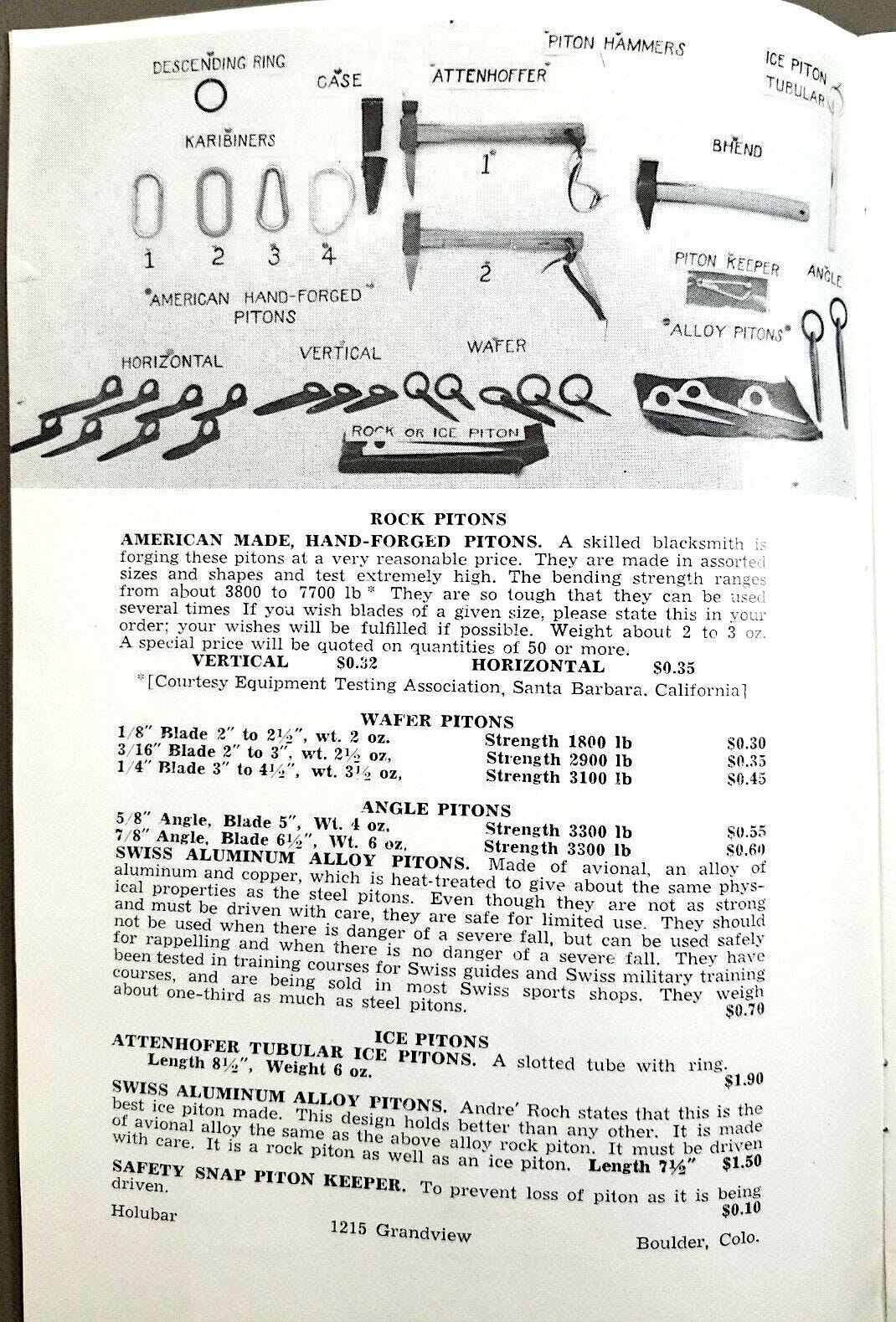

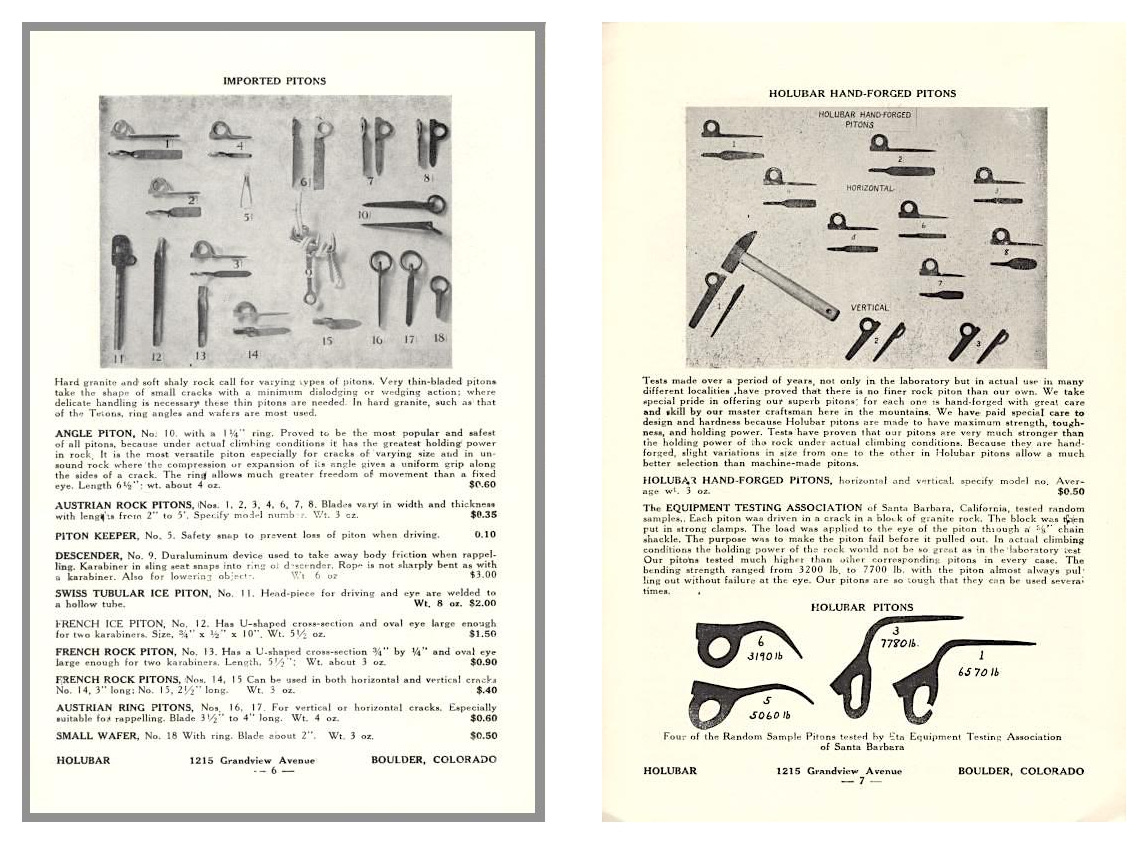

In the 1950s in North America, most pitons used for climbing were made in Europe, where the fullest range of size and price options were available. There are a number of references of climbers buying equipment from Sporthaus Schuster in Munich, including the ASMü pitons (produced by August Schuster) used by the Stettners on Longs Peak in 1927 (story next post). Some of the highest quality pitons came from Switzerland, though these were only available in the USA from specialty retailers such as Abercrombie & Fitch, who were selling pitons made by Hupfauf. Fritsch and CCB also produced quality pitons in Switzerland. The Swiss pitons appear to be made from higher grade steel than the typical mass-produced mild steel pitons from the major post-WW2 brands: Cassin, Simond, and Charlet Moser, and Stubai, but further metallurgical analysis would be needed to confirm this. Throughout Europe, there were still a number of smaller manufacturers creating custom pitons for climbers, all using various grades of mild steel, but store-bought pitons were plentiful and relatively cheap, so they became the mainstay of a climber’s ‘rack’ of gear.

Review of Steel

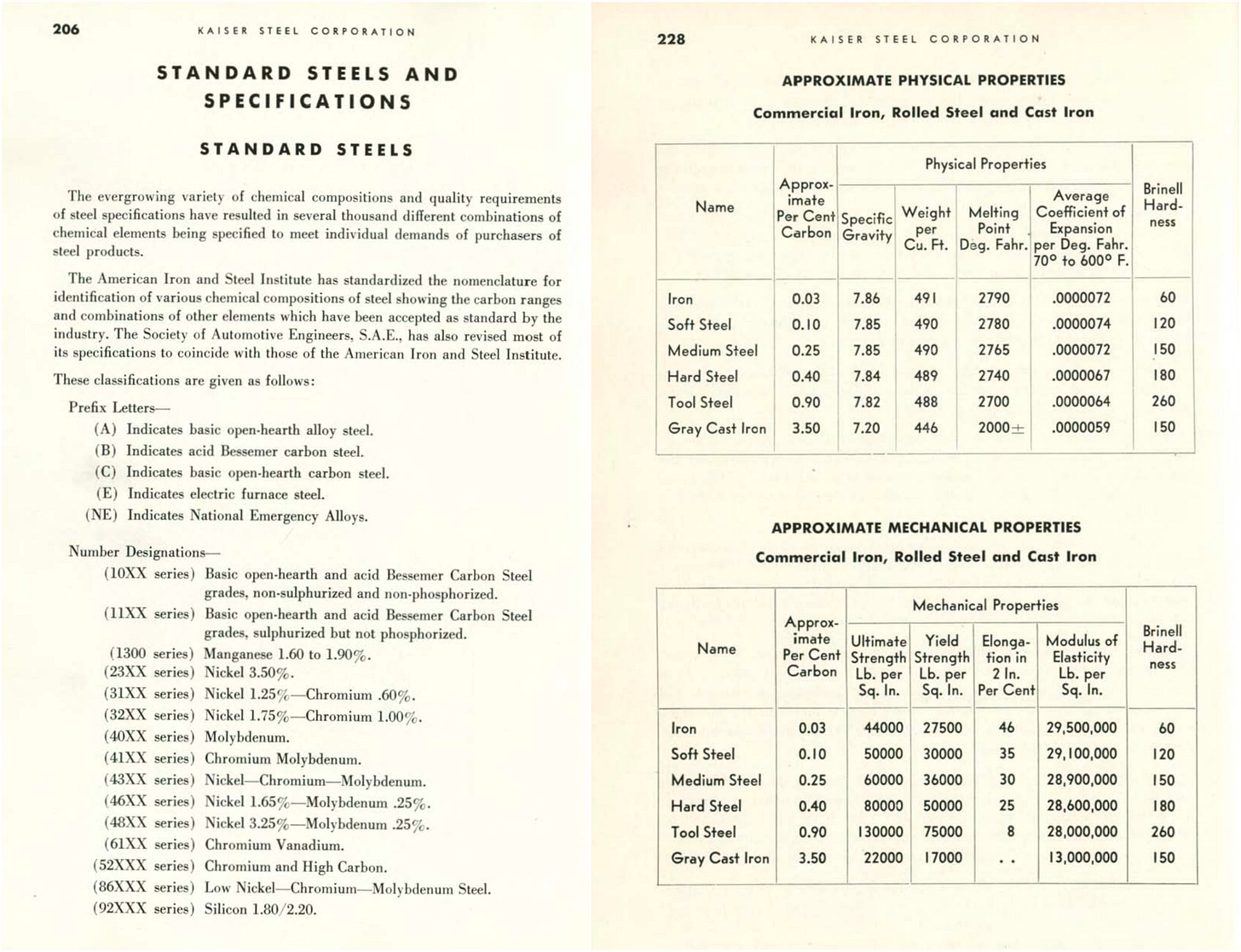

Most pitons made in Europe, well into the 1960s, were made from mild steels. Engineers and climbers have all sorts of confusing names for steels with various amounts of carbon, such as low-carbon/low tensile steel, 10/10 steel, ST37 (Europe), ‘sweet homogeneous iron’ (Bonatti), etc. (“soft iron” is a long-standing misnomer, as the pitons are steel, not iron). Mild steels (SAE 1000 series) are relatively soft and malleable with a maximum hardness of around Brinell 120, so not suitable for super-thin pitons (as they will buckle) or for angle pitons (as will tend to flatten out when getting hammered into a crack). But for the mainstream mass-produced “horizontal” and “vertical” piton designs optimized for the limestone cracks of the Alps, mild steel is strong and robust enough for a few placements, and was suitable for a low-cost piton.

High-strength steels used for pitons also have a number of names, Chromium-Vanadium (CrV), Chromium-Molybendum (ChroMo, Chromoly, etc.), as well as many other alloyed steels. Alloys steels like these can be hardened to Brinell 300 and still be tough (RC41/42 makes for a nice knifeblade piton hardness).

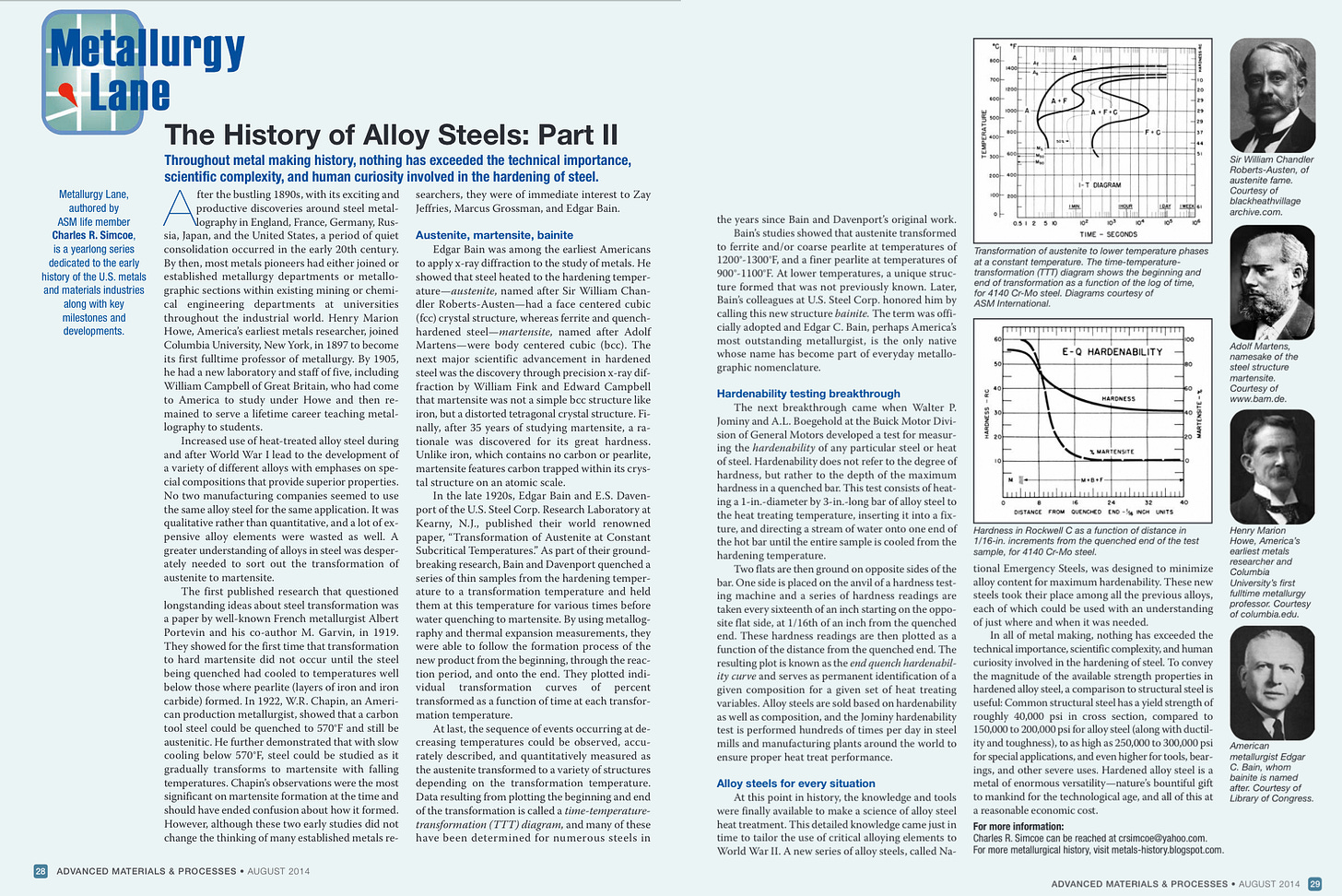

For the purposes of steel climbing pitons, perhaps it is easiest just to refer to the original steels used for climbing pitons as “Mild Steel”, and higher strength piton steels as “Alloy Steel”, with alloys such as chromium, vanadium, molybdenum, etc. in just the right trace amounts enable the steel to be stronger and harder by optimising grain structure with heat treatments, which fine-tune the hardness and toughness—the measure of bend before breaking/ductility—of the steel, which are inversely related for a given type of steel. More on 20th century global steel evolution here.

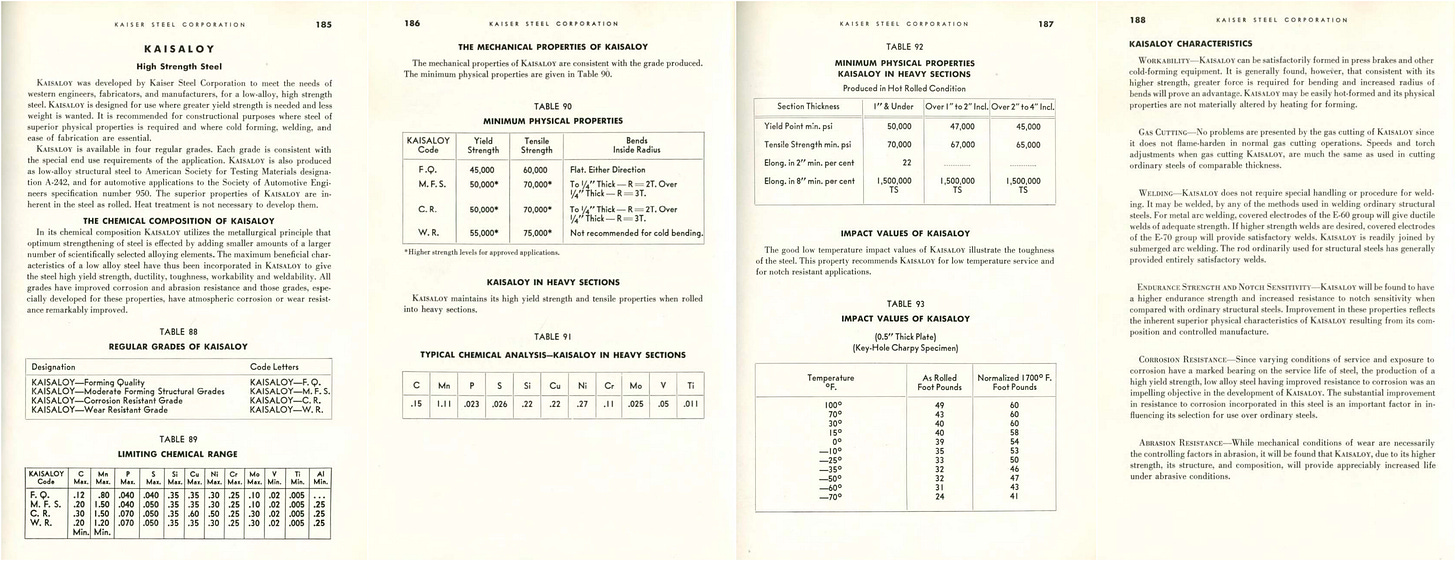

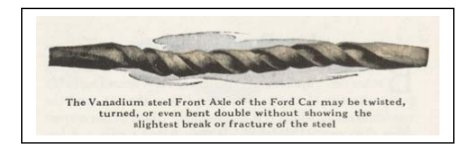

There might be other types of steel used in the evolution of pitons, perhaps we can call them “Medium-Strength Alloy Steels” to differentiate from the more common high-strength alloy steels available today—steels with a higher degree of hardenability than mild steels with good toughness properties and with some alloying elements, a developing science in the 1930s-1940s. I believe most climbers of this time could intuitively differentiate when pounding different types of steel pitons on their racks from various sources, though knowledge of the types of steel was often not shared between manufacturers and nations. USA steel producers became the world’s largest in 1901, and for the next five decades were global leaders in high-strength steel research, driven by the automobile and aircraft industry. (See also Simcoe). It appears that some of the early USA pitons were made from higher quality steel than was commonly used for pitons in Europe at the time. It is not unthinkable that a blacksmith’s simplest source for high-grade alloy steels was from abandoned industrial parts like the crankshaft of an old Ford (it is still a point of pride among backyard blacksmiths to repurpose metal parts and tools). After WW2 in USA, many new alloy steels with a wide range of properties became more common and were used for small batches of pitons and other parts by the occasional crafty blacksmith among the climbing community.

Chuck Wilts is acknowledged as the definitive source of awareness of 4130 steel as a piton material. He also clarified, from the material science engineering perspective, how the heat treatment process was the most critical design feature of making pitons. Chromoly steel (4130) in the 1950s was becoming one of the more common high-strength steel alloys, with very versatile heat treat hardenability for a variety of steel tools. See this post on the A5 Hammer production for a more detailed example of creating a forged 4130 steel part in the 1980s.

By the 1950s, small-scale heat treat shops were a growing industry. In the 1940s, John Salathe probably heat-treated his famous Lost Arrow pitons in his shop. Heat treatment involves quenching the piton in oil or water from a high temperature to lock in the martensitic grain structure and results in a very hard and brittle piece of steel. Then the part needs to be tempered in an oven at a very specific temperature and for a very specific time (the developing science w/ 20th-century steel production and use).

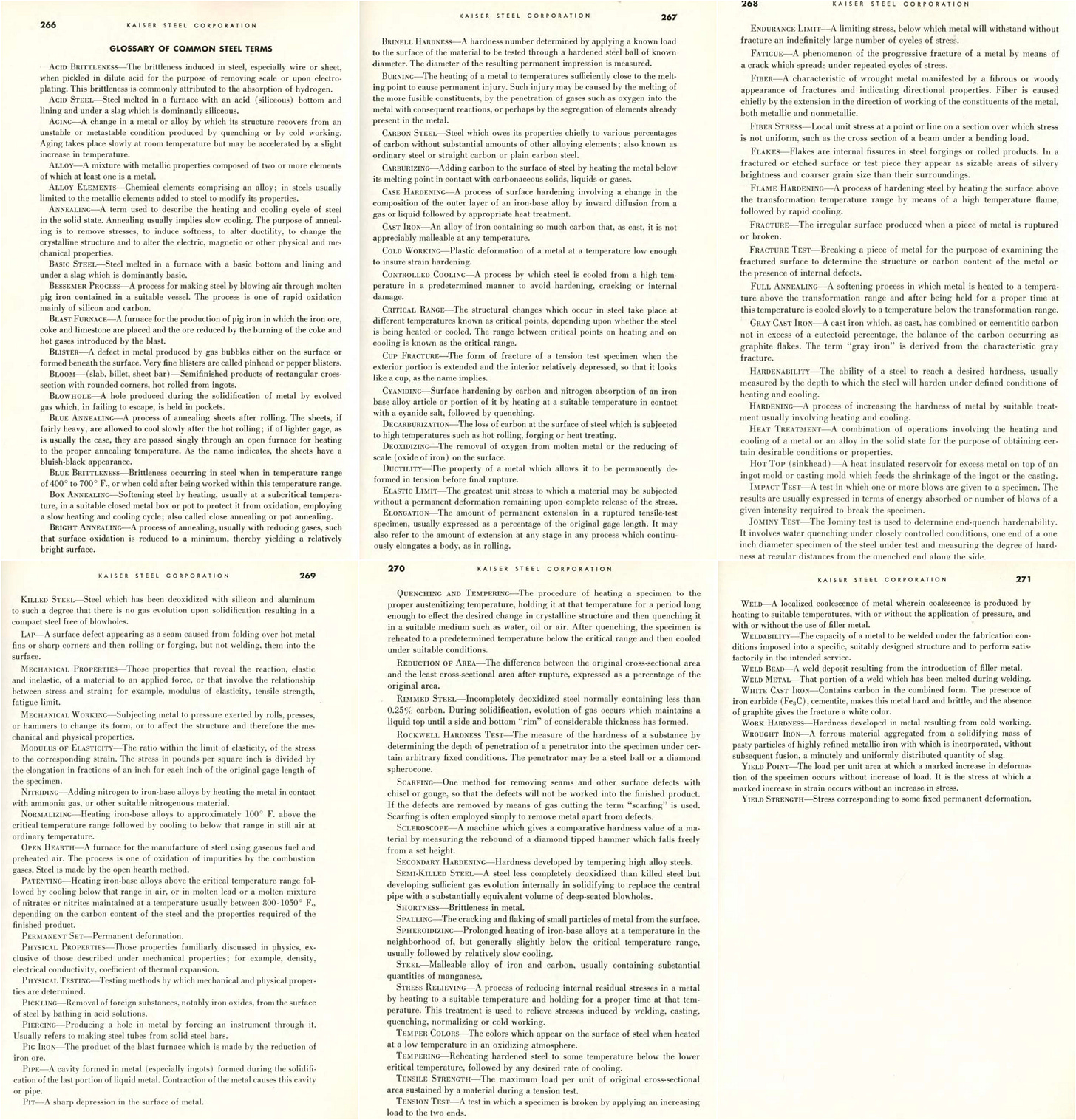

Steel Reference Information, 1953

Steel catalogs like the 1953 Kaiser Steel General Catalog were (and still are, in fact) valuable references for a blacksmith in terms of workability and production of steel parts from billets, plates, sheets, and other semi-finished steel products used as raw material for new tools.

Chromoly Steel

Lots of names: Chrome-Molybdenum, ChroMo, Chromolly, Chrome-moly, take your pick. These 41xx series of steels (4130, 4140, and 4340 are common grades for high-strength pitons and hammers). Today, these alloys are some of the most common high-strength alloys found from most suppliers, but in the 1950s and early 1960s, the major producers did not list a wide range of sizes in these alloys in their catalogs (interesting history of 4130 tubing here). So the original material for a range of medium- and high-strength alloy pitons prior to the 1950s would probably involve a wide range of alloys. But when Chuck Wilts published his research in the Sierra Club Bulletin, 4130 was recognized as the ideal material for climbing pitons, and suppliers found.

Rough Material Chronology

So with that in mind, here is the rough idea of steel piton material evolution:

1900-1960s Europe—mostly mild steel pitons. Some of the early Swiss pitons (1930s+) might have been made from higher quality European steel than commonly used mild steel for most pitons at the time.

1920s-1940 USA made pitons: mostly mild steel, though some pitons made in smaller quantities might have been made from medium-strength alloy steels (Dwight Lavender and Bill House pitons TK).

1943: US Army mild steel ring angle (probably 1020), vertical and horizontal pitons. Tens of thousands of these were made for anticipated mountain warfare, and unused stock flooded the market in 1946.

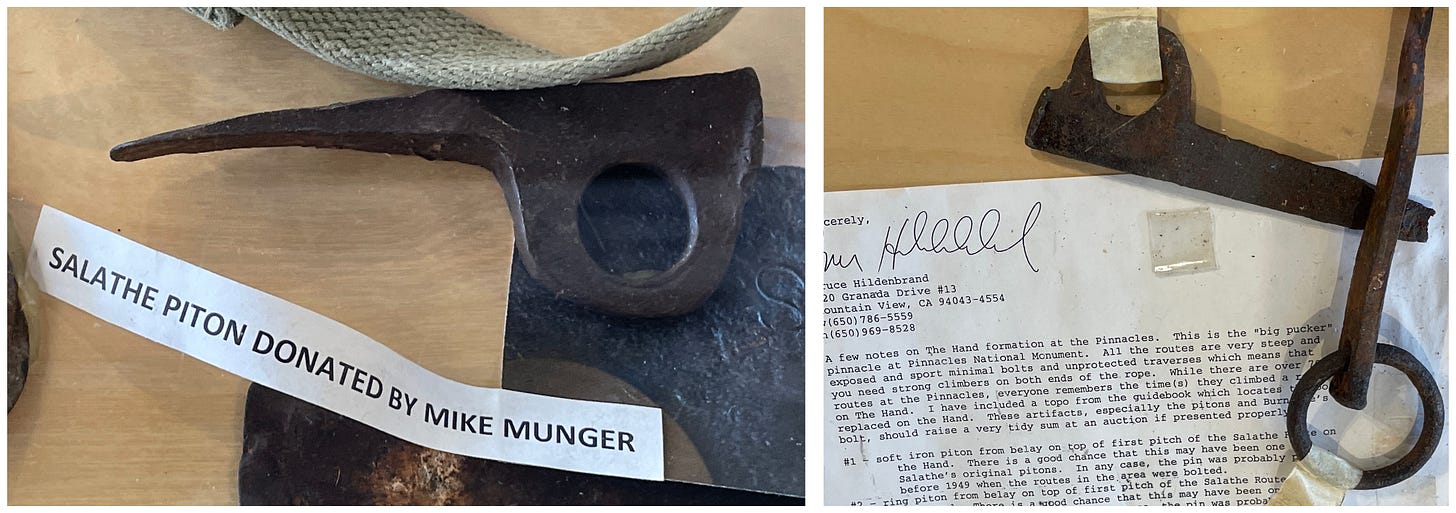

1943 US Army pitons made from mild steel. Not many of the Army horizontals seem to survive. Note also the reference to “soft iron.” Image courtesy Karabin Climbing Museum ~1946: John Salathe uses high-strength Chromium-Vanadium (CrV) alloy steel to make pitons for his climbs in Yosemite. CrV can be hardened precisely with heat treatment, quench, and tempering to get the optimal balance of toughness, hardness, and strength.

1946-1954: in the USA, Bob Owens (Kachinas), Bob Bruning (Holubar), and Norton Smithe possibly also made pitons with a medium- or high-strength alloy steel in this period.

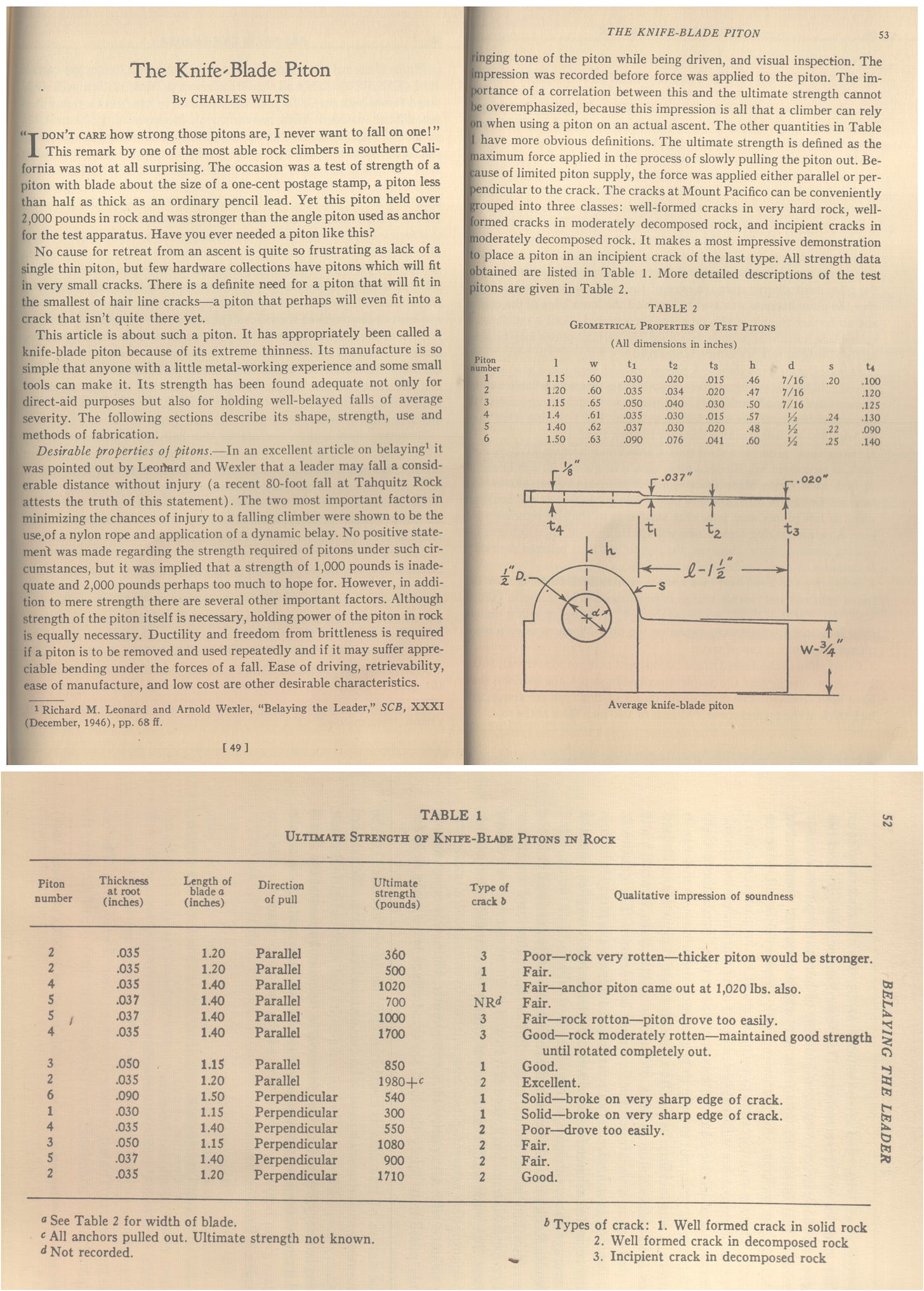

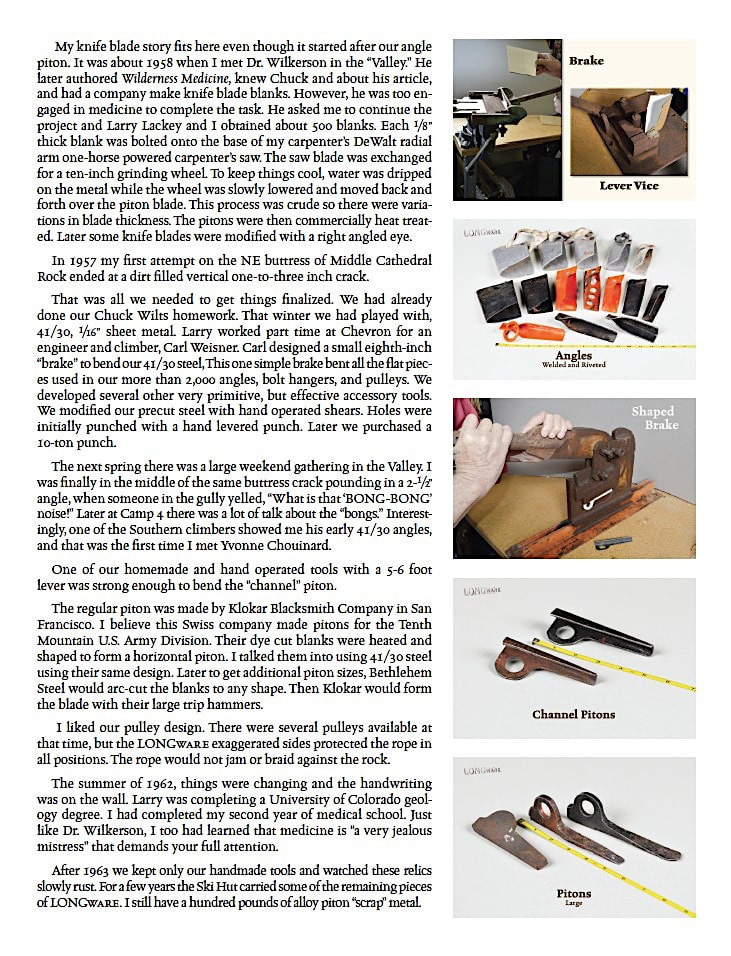

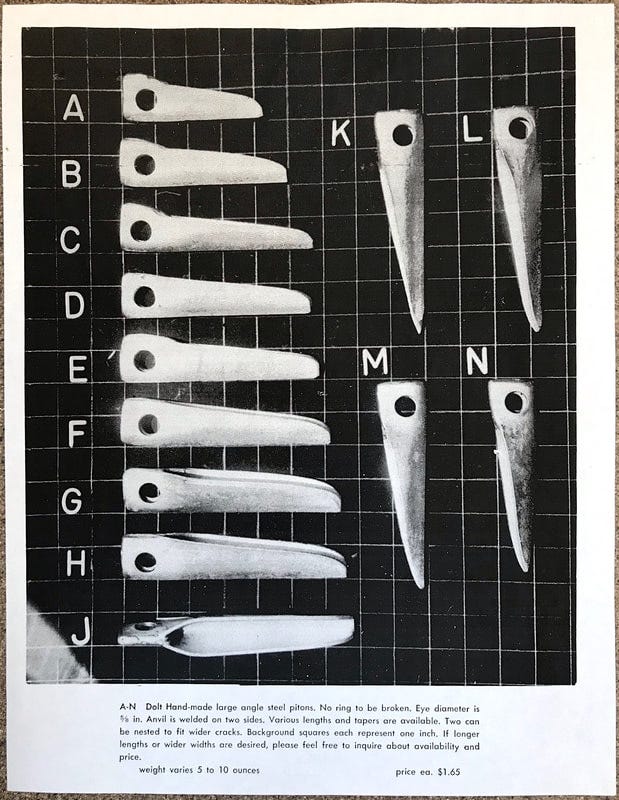

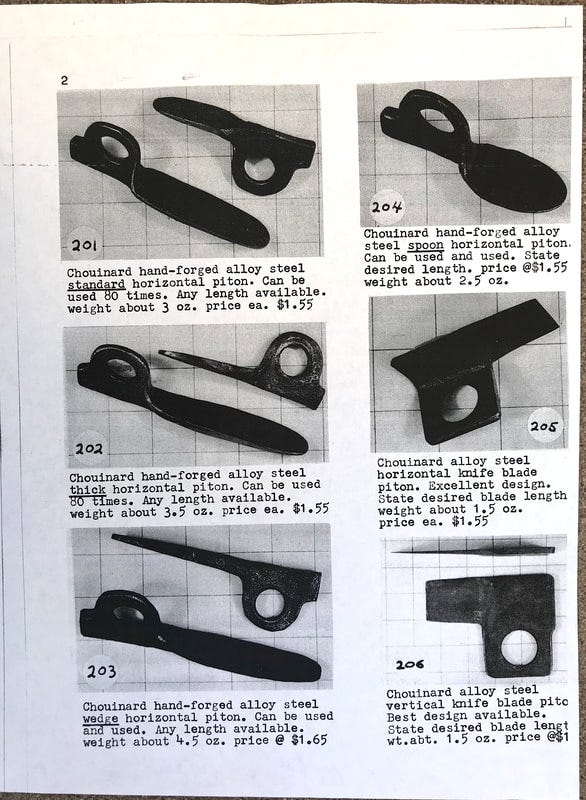

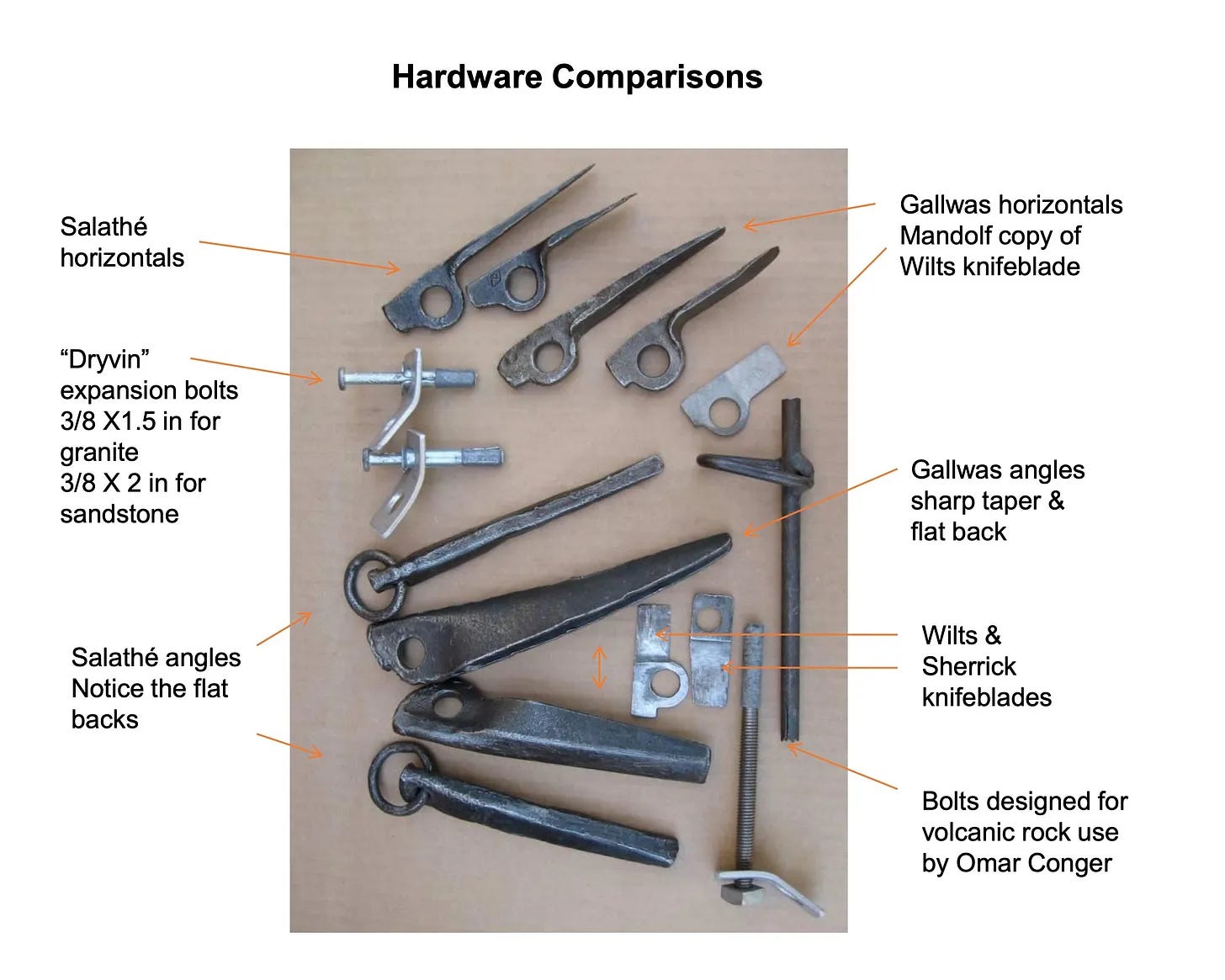

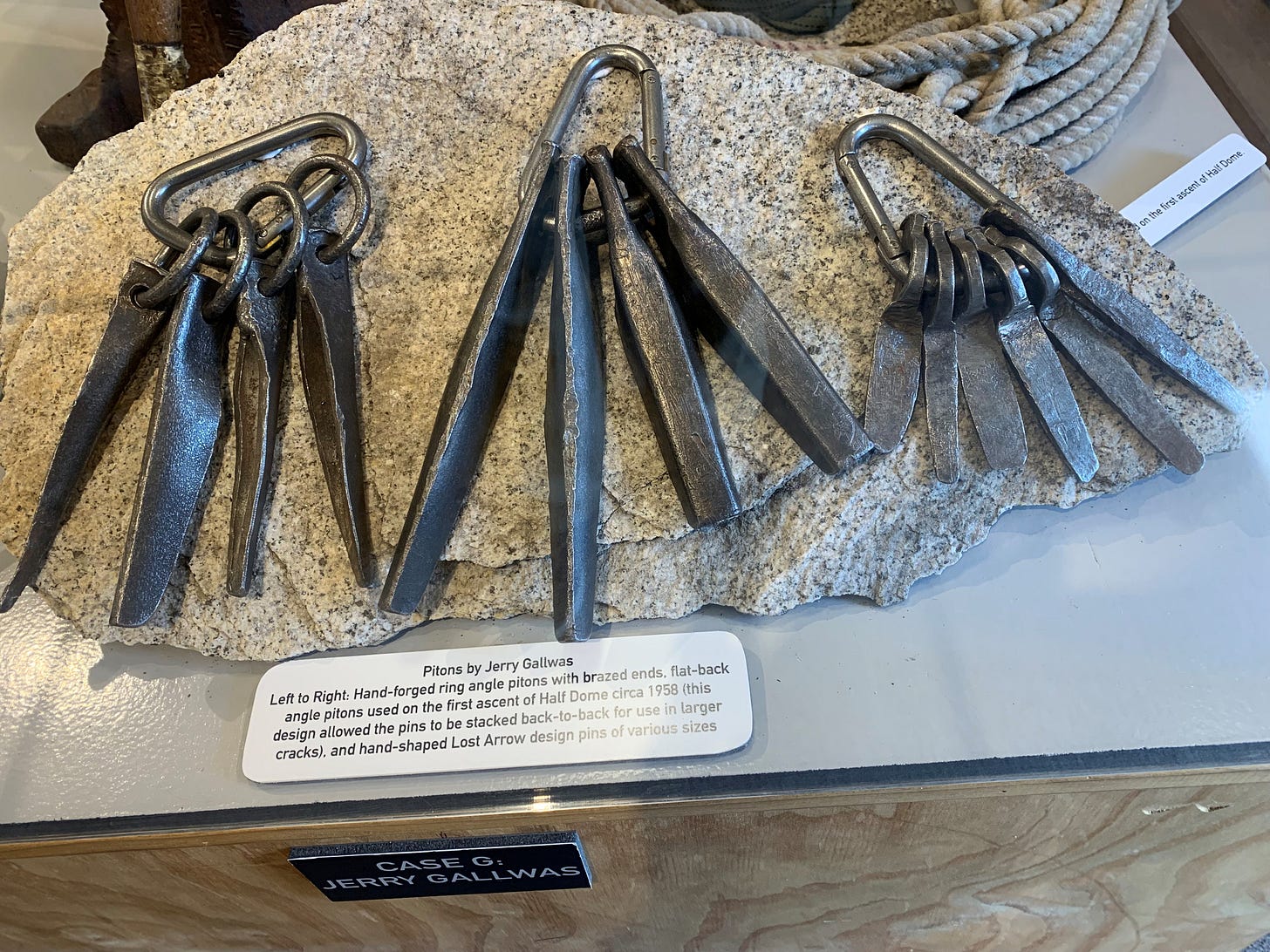

1954: Chuck Wilts shares information on his 4130 Chromoly thin pitons in the Sierra Club Bulletin (and in “Belaying the Leader, an Omnibus on Climbing Safety”, 1956) and soon a number of makers begin making Chromoly pitons, which then becomes the standard for all high strength steel pitons, craftsfolk include Richard Long, Jerry Gallwas, George Rea, Bill Feuerer, and Yvon Chouinard.

1950s USA-an age of piton innovation.

Typical climber’s“Rack”: In the early 1950s, most American piton climbers would have had a few army Gov’t surplus pitons, a selection of “soft-iron” (mild steel) pitons brought over or shipped from Europe, and perhaps a few high-quality hand-made steel pitons from a USA designer and maker. Carabiners would have been a mix of steel and some aluminum. Racks of gear were heavy, and limited in the range of sizes (~3mm to 10mm widths). The time was ripe for another gear evolution.

Designing new gear for the new big wall challenges on the granite and sandstone mountains of the North America led to a productive period of equipment innovation in the USA, with arguably four ‘centers’: California, Colorado, Washington, and the East Coast. This story will be told in two parts, 1920-1940, and 1940-1960s. This page as reference material below, and will be updated with further research and as others contribute. Many thanks to Marty Karabin (MK) and Ashby Robertson (AR), whose images are noted below. Other sources TK.

Information from those who were there:

Writing online has been a great process. My initial research is often enhanced by contributions from historians around the world, and I am able to update pages with new, relevant evidence in the ongoing story of tool and technique evolution in climbing.

Richard Long, Jerry Gallwas, and Jim Erikson have recently responded with experience and more details of materials and processes, and along with historical American steel manufacturing records, a clearer picture emerges of early USA steel pitons.

Richard Long Recollections 8/29/2022

(See Longware hardware collections in prior post). Of interest to tinkerers!

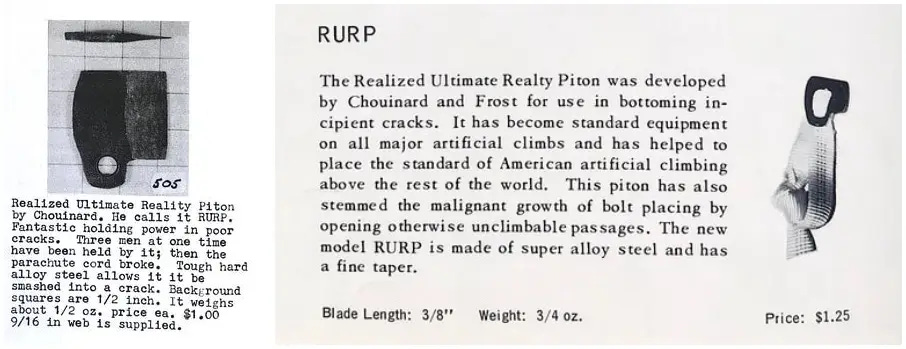

RL: Longware was initially formed by Larry Lackey and me. After his injury on the Higher Spire, Larry gave up climbing and went on to be a successful “precious metals" hard rock geologist.

Q: Do you recall your material suppliers, and what stock material you were ordering (billets, sheets, etc.).

We purchased 41-30 steel and later 7075 aluminum alloy from, I believe, Bethlehem steel in Oakland CA.

Q: Did you do your own heat treating?

Heat treatment was done commercially. I would wait until I had several hundred pounds of finished material and send in one big batch. After the initial high-temperature treatment, the metal was held for an additional 24 (?) hours at 450 degrees. I had items treated with a phosphate coat as anti-rust and suitable for painting.

Could you tell me a bit more about how you designed/made your angles and your knifeblades?

One of my friends was Dr. Wilkens, MD from LA. and had also read Wilt’s article. He had enough money to hire a machine shop to make a dye punch to Wilts’s specifications. It would punch through 0.093 inch 41-30. I figured out a way to grind the blanks to the proper size. Ideally, they should have been pounded to that size. After several years he lost interest and asked me if I wanted the dies. Dr. Wilkens went on to write several mountain medicine books.

Bethlehem steel used an arc plasma cutter to form the shape for my horizontal pitons. They were cut out of 1/4 or 3/8 inch 41-30 or 86-30 flat sheet metal stock, Then I hired Klockar Forge in San Francisco to drop hammer forge the blade. I punched the eye at home with my personal punch.

All my equipment was made by hand. It was cheap, but worked.

Richard adds: “I really didn’t pay much about who and what was going on or being done. Of Interest, Harding and I would go to the Bay area local practice climbs. I would show him my heavy angle iron attempts and he would show me his latest “stovelegs”. However, when Chuck Wilts knife blade article came out, I learned about 41-30 steel and knew this was the answer! I also knew Chouinard was doing something. In 1957 or 8, I was on the Higher Cathedral buttress, the people who heard the sound named them “bong-bongs”. After the climb, Chouinard and I showed each other what we had been doing. His wide angles went to 2” and mine to 3” and some of mine were relieved. The competition was on. I believe Chouinard would have won regardless. He was totally devoted to climbing! Not afraid to develop something that might work. I had many interests including a wife, two kids, high school teacher and I was trying to get into Med School. To this day Chouinard and I have always remained good friends.”

Thanks Richard!

(more pictures from Richard will be added soon)

Jerry Gallwas

Jerry Gallwas also recognised 4130 as the ideal choice of alloys early on, and was influential in the development of American climbing hardware.

Jerry summarises his contributions below (8/24/2022):

John,

Please pardon the delay in my answer to your E-mail on my exploration into the development of pitons in the 1950s. Sandy and I have been in Scandinavia for the past few weeks, and I have been delinquent in keeping up with E-mail. This is being written as we wing our way over the North Atlantic. I summarized my experience in piton craft in my writeup of the First Ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome. I was inspired to go into rock climbing by the Ansel Adams’ photo of Salathe and Nelson on top of the Lost Arrow that was displayed on the front of Best Studio when I visited Yosemite in 1949. I knew nothing of rock climbing but at the moment I saw the photo I knew I wanted to stand where Salathe was standing and take that photo. A few years later I did just that when Wayne Merry and I made the 5th ascent of the spire. The Ansel Adams’ photo led me to the Sierra Club Journal article by Anton Nelson of their experience and thus the information on heat-treated alloy steel as the intelligent alternative to mild steel which was the basis of all commercial hardware at that time. I lived in San Diego, an aircraft industry city, and so had friends familiar with 4130 Chrome Molly steel and its heat treatment. Chuck Wilts’ experience reinforced my conviction that 4130 was the right choice. Over the years I climbed from 1951 through 1957, I made pitons, horizontal, wafer, and angles for my own use and for friends. Most of the remaining pitons from my climbing days are on display at the Yosemite Climbing Association Museum in Mariposa California. I still have a handful of unused ones but all the hardware and associated gear is in Ken Yager’s possession including the anvil. My grades and draft notice came in the same mail in 1962 and so the climbing student moved on to defend the country. In 1966, I took a 150 fall that ended my climbing years.

Cheers, Jerry

Q&A with Jerry Gallwas:

Q: In 1952, you were using 4130 steel for making pitons in Coronado. Do you recall the stock material you were able to buy? (i.e. round or flat stock, size?). And regarding heat treatment, in your writings, you reference Henry Mandolf, was he an engineer? You were forging pitons, I understand--did you use a punch to make the eye, or some other method?

It was bar stock, 0.25” x 1.25” 4130 from a local metal supply store, a big place. The heat treatment was in a salt bath of a commercial operation. Henry Mandolf was an engineer and owner of Langley Corporation a supplier of parts to the airframe industry in San Diego. He had been chief engineer at Consolidated Aircraft in San Diego during WWII and formed Langley Corp. after the war to design spinning reels. He climbed or skied every weekend and was a mentor to us teenagers who had more energy than judgment. I forged the pitons by hand on an anvil we had found in an old mine on a backpacking trip, drilled the eyes, and finished off the edges with a grinder then had them heat treated on Henry’s account. He was a great guy. He provided the station wagon and gas and we did the driving.

Q: You mention using soft steel for your angle pitons--I am under the impression from talking to Hermann Huber (Salewa), that mild steel didn't really work well for bigger angles, as they would flare out when placed, and that is why they didn't make angles until after they had seen the successful USA chromoly versions. Maybe you had a medium-grade steel?

I originally made angles from bed stead stock and then wider angle soft steel. But the real success was to go to ‘U’ shaped stock that gave rigidity to the soft steel. The could be used in pairs for wide cracks and were very useful in sandstone. You can see the “U” shaped angles in the attached Half Dome gear display in Ken Yager’s Mariposa Yosemite Climbing Museum photo.

Q: Can you tell me any more about Chuck Wilt's process--was he cutting and milling to make the original knifeblades, or did he also forge some pitons? Do you know when he might have made his first pitons?

Chuck Wilts describes his Knife Blade piton in detail in the Sierra Club Bulletin of Jun 1954, page 71-77. He basically used a saw, drill, and grinder for the manufacturing process. They were very good and we used them a lot. Henry Mandolf had his model shop manufacture a couple of dozen for us so we were never with out.

Jim Erickson

When I started climbing in the mid-1970s, there were still a few diehards with hammer and pitons on their racks. But clean free climbing was cooler (I nailed a few pitons when I first started to climb, but only learned pitoncraft when I started climbing El Cap nailing routes in the 1980s). To me, the Colorado climber Jim Erickson was one of the most inspiring climbers of my early era, as he was one of the best on-sight free climbers, known for bold downclimbing incredibly difficult sections to avoid any fall or weighting of the rope, as any aid on the route diminished the spirit of any ground-up future ascent; Jim’s style became my ideal for most of my climbing career.

Prior to the clean climbing revolution in the early 1970s in the USA, Jim’s climbing in the 1960s involved pitons; in terms of piton-protected hard free climbs, Jim’s routes were some of the most feared and difficult. It is quite an art to place a good piton in the middle of 5.11 moves (we call this, “pitoncraft”).

Jim provides valuable information about the European pitons in the later 1960s, and more about Colorado manufacturers. The Europeans were also starting to use more hardenable steel, but it’s probable these were still mild steels with a maximum hardness of ~Brinnel 200. Jim reports the Charlet Moser pitons were best for multiple uses prior to Chomoly.

More Chronology 1940s-1950s

TO BE UPDATED WITH MORE EXAMPLES AND DESIGNS: Bob Owens, George Rea, Jerry Gallwas, Bea Vogel, others…

MORE 50s and 60s To Come: 4130 Chrome-moly steel consolidates as the standard piton material for all USA-made pitons.

Addendum with more information from Richard Long and Jerry Gallwas here.

CMI, Forrest, and SMC also begin making quality hardware in the 1960s (TK).

Slings in 1956: 1” military spec woven nylon webbing

Rock Shoes 1957

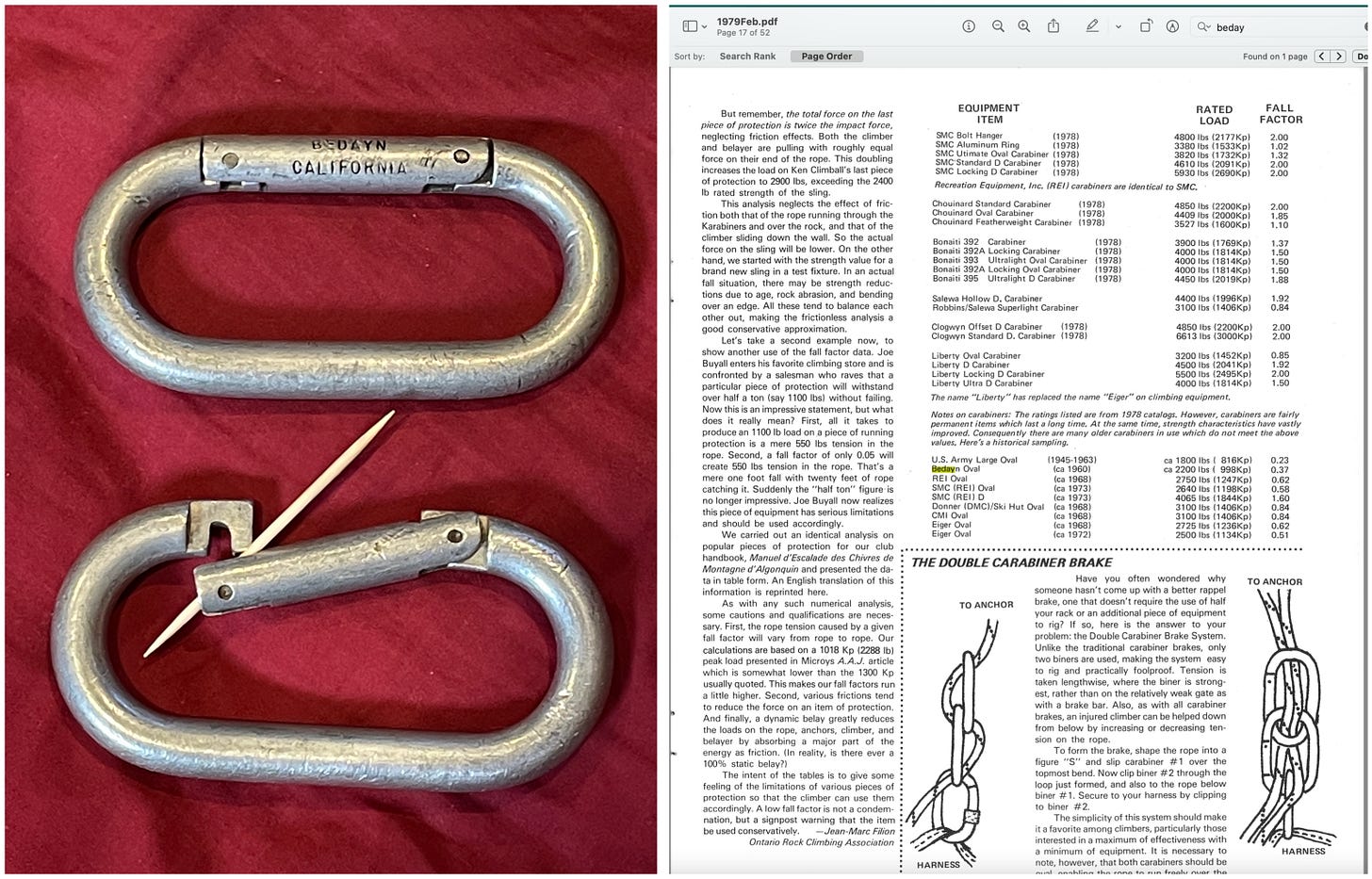

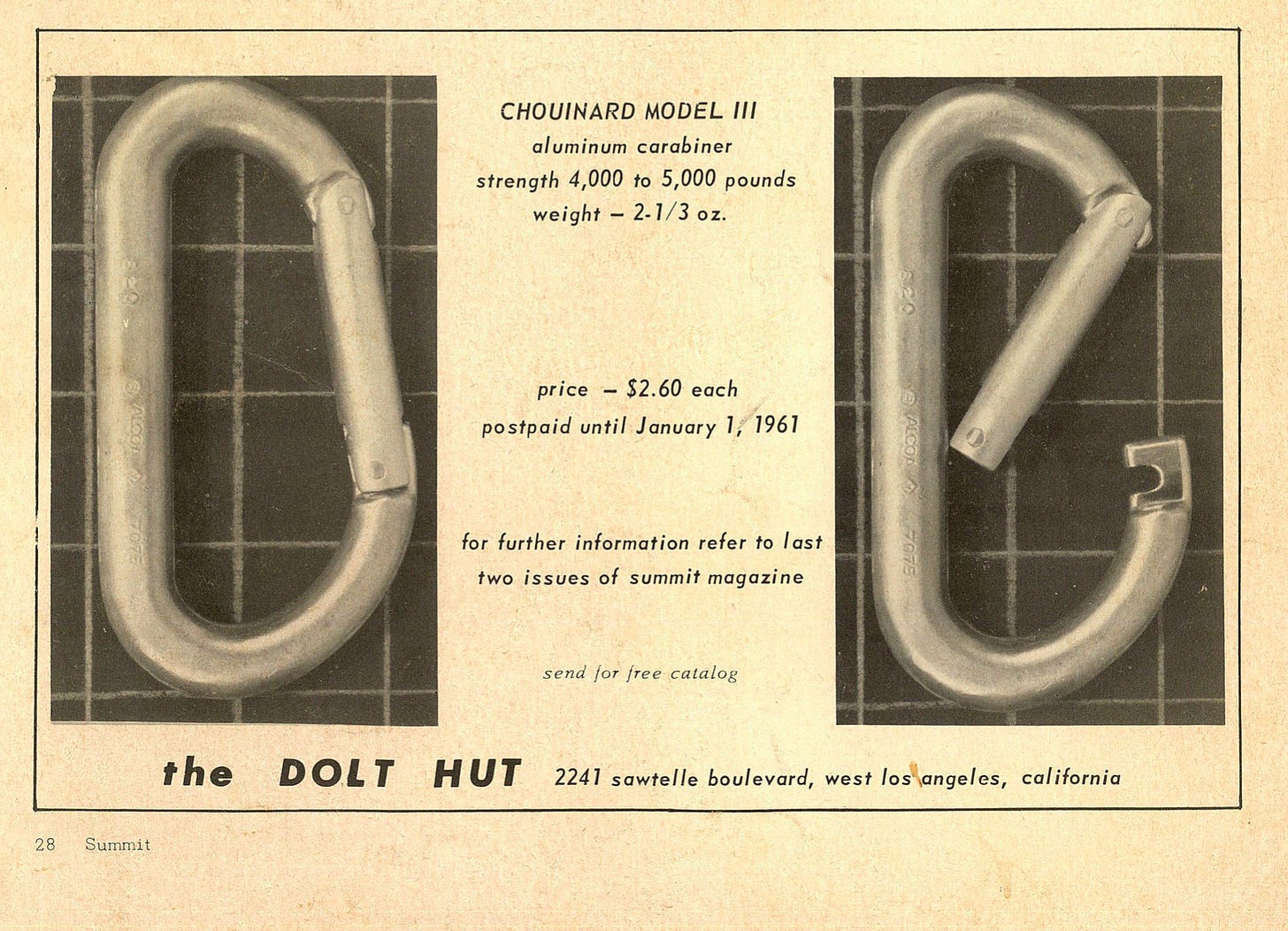

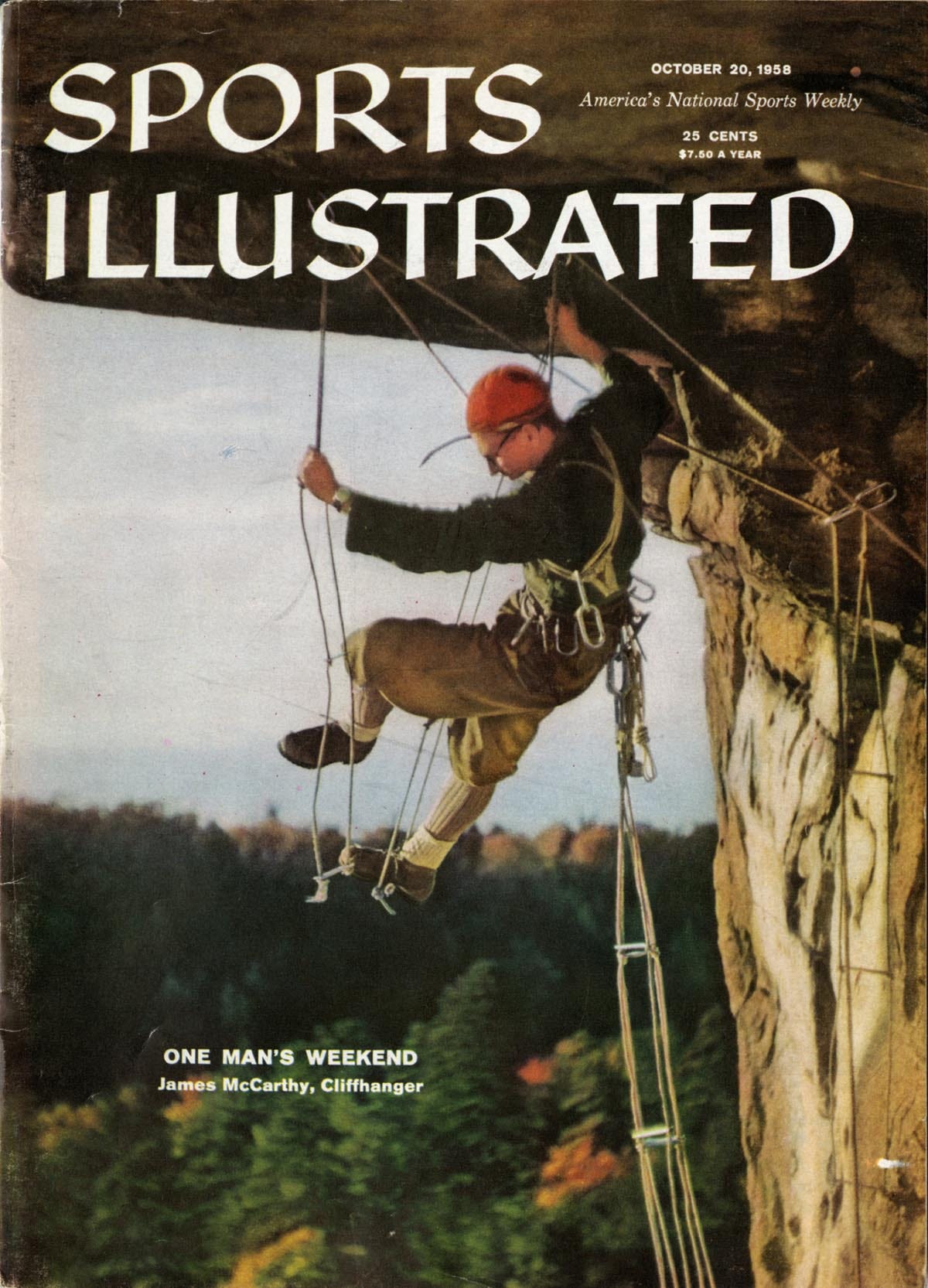

Best Big Wall Carabiner 1950s:

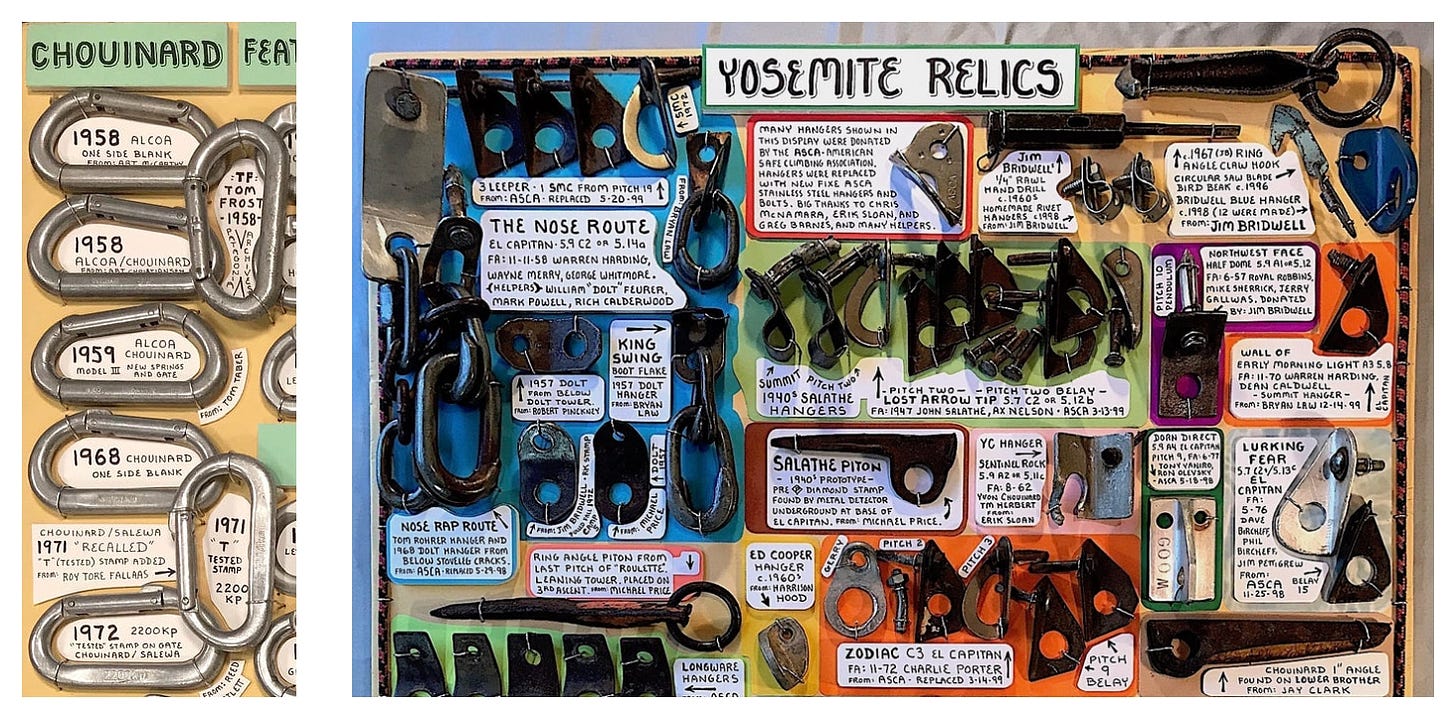

Best Big Wall Carabiners 1958-1961+

Studies/Tests

MUSEUM COLLECTIONS

American Alpine Club, Golden, Colorado:

Gary Neptune, Boulder, Colorado:

Marty Karabin, Phoenix, Arizona:

more random notes:

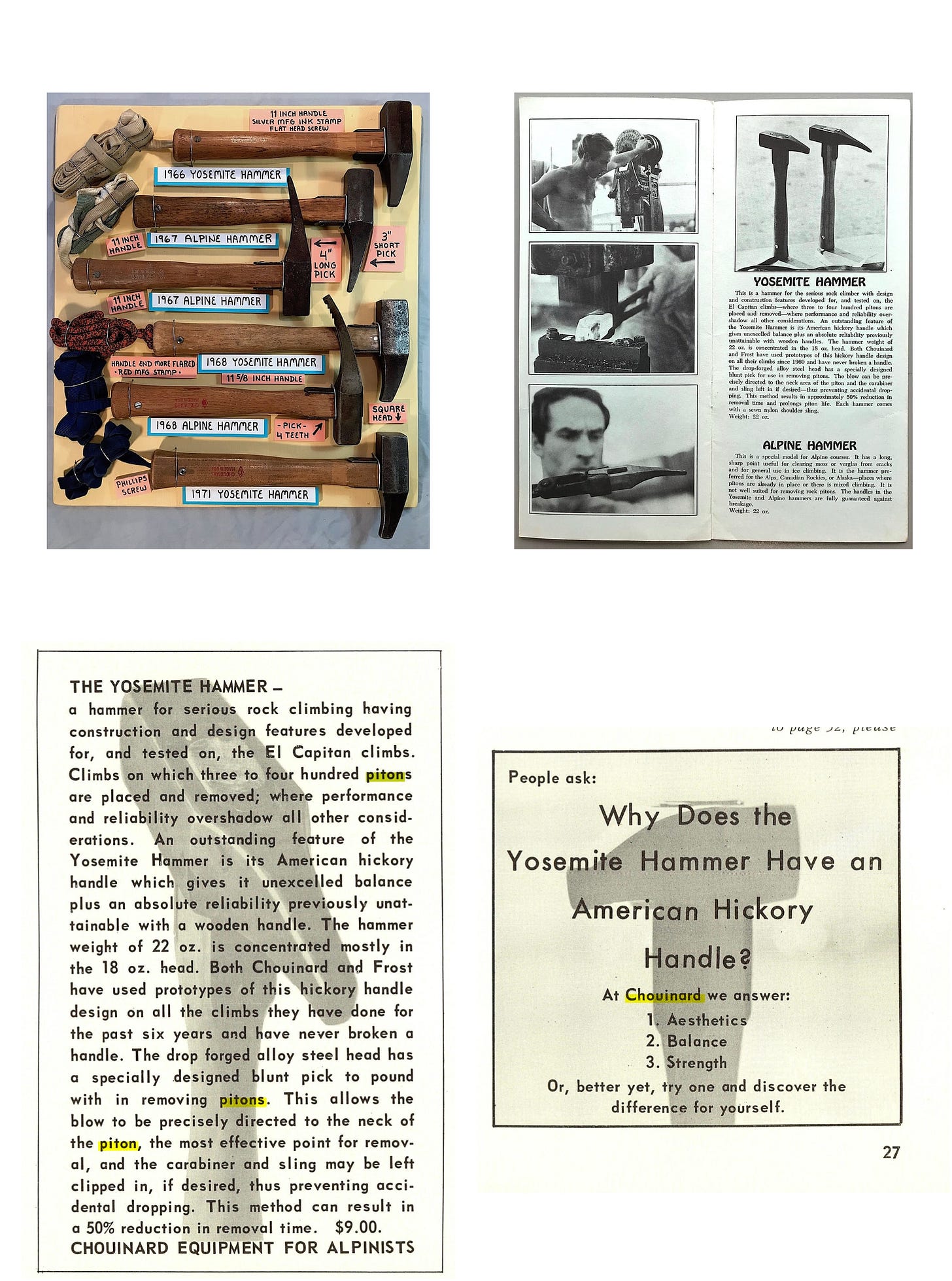

More on A5 hammer development as a study in chromoly production drop forging…

Appendix

Using my alloyed attention span, I read this whole piece. What a superb tour de force! Especially fun for me was seeing my acquaintance Jim Erickson's opening words: "Most of the following is probably true."