Prologue to Tasmania Treesit Research

bits of early environmental activism history in the forests of Australia and New Zealand

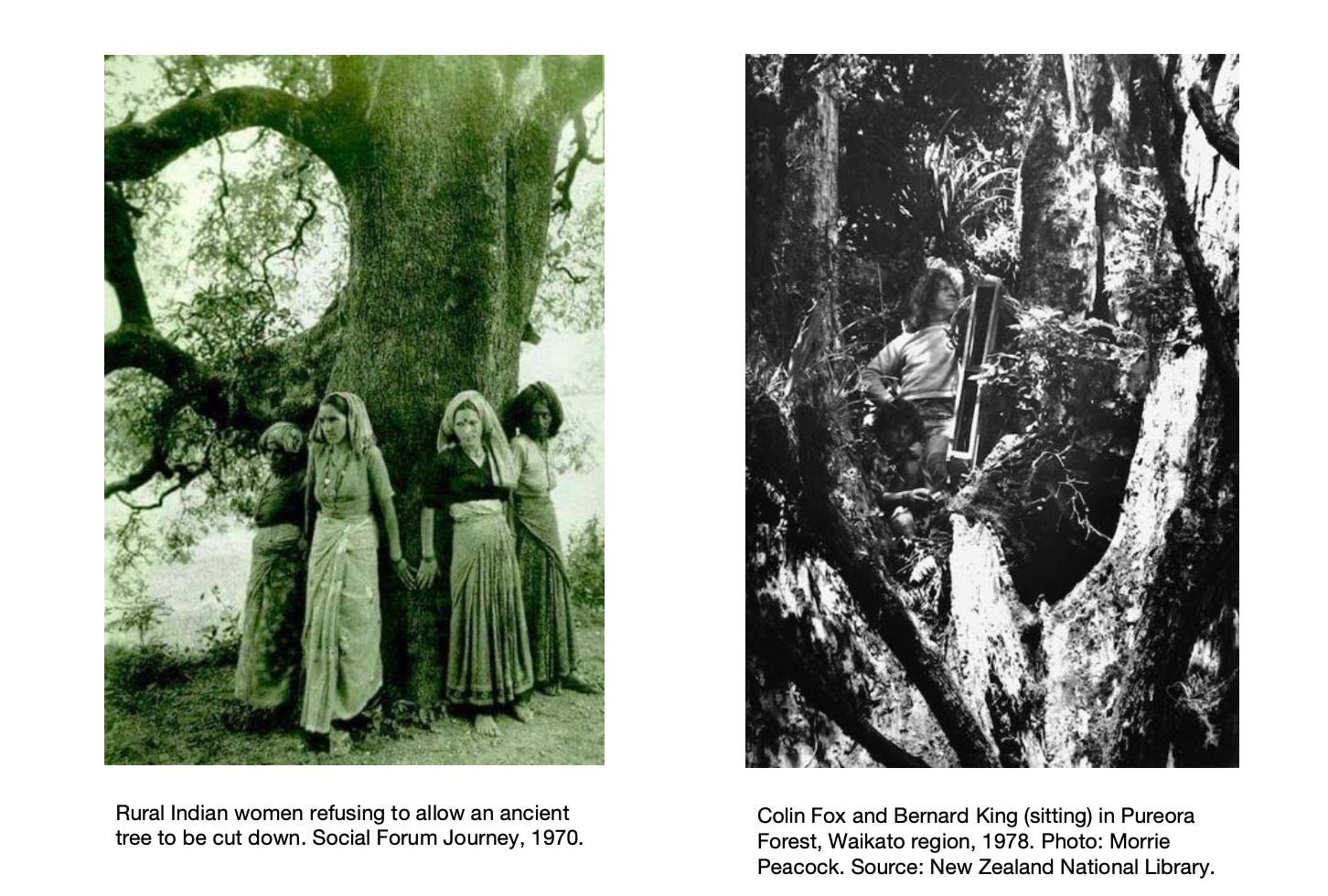

Trees and humans periodically work together to stall the decimation of their mutual benefit. In 1973, the Chipko movement began an effective human blockade in India to preserve a forest ecosystem. Their tactic was simply to hug the trees soon to be felled by axe, and not let go. What began as a small group of tree-huggers spread to over 150 villages in the valleys of the Garhwal Himalaya. The wide-scale actions clarified the importance of top-tier ecosystem preservation at the headwaters of great rivers and led to a tree-felling moratorium and acknowledgment of Himalayan forest rights by the state government.

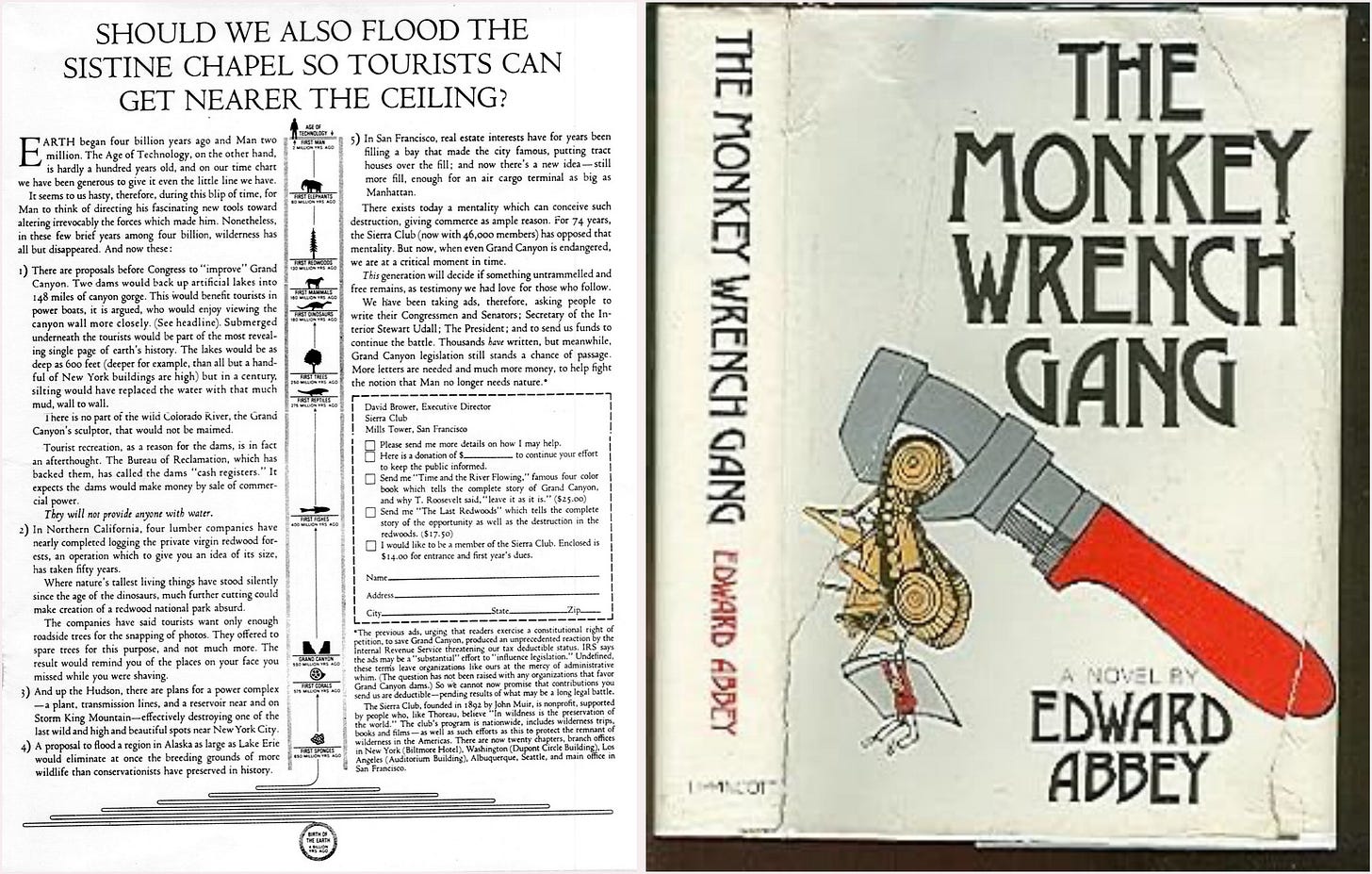

In the antipodes, organised protesters took the tree-hugging idea further, and in 1978, a group of conservation activists built small platforms in Totara trees within the ecologically diverse Pureora Forest on the North Island of New Zealand, as part of a structured campaign organised by the Native Forest Action Council (NFAC). Totara trees can be 4m in diameter and grow up to 35m tall and provide perfect notches for constructing tree house platforms high in their canopy. With protestors on the ground also preventing access to the base of the trees, logging was fully halted, leading to public awareness and political action, and the rainforest gained legal rights as Pureora Forest Park.

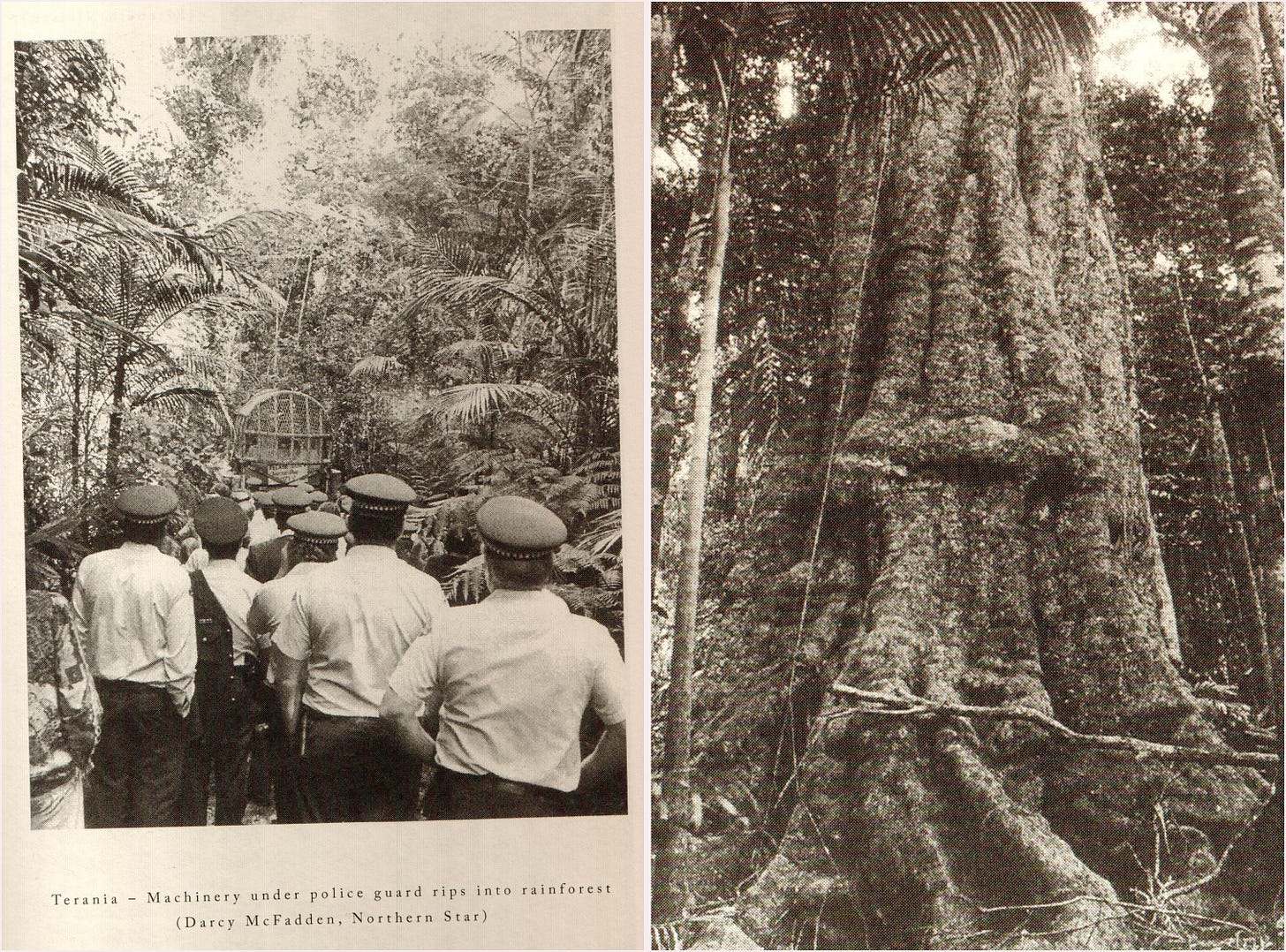

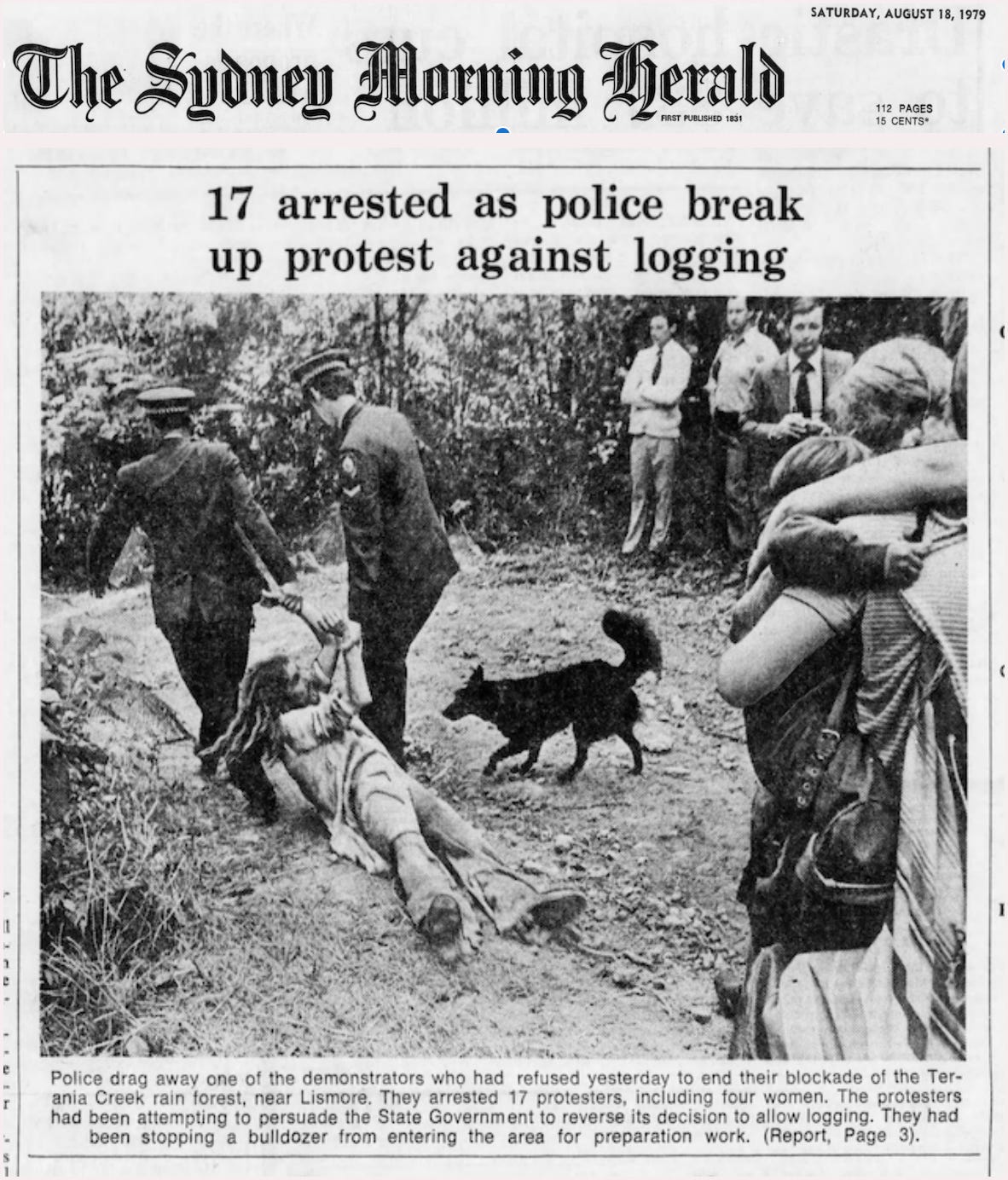

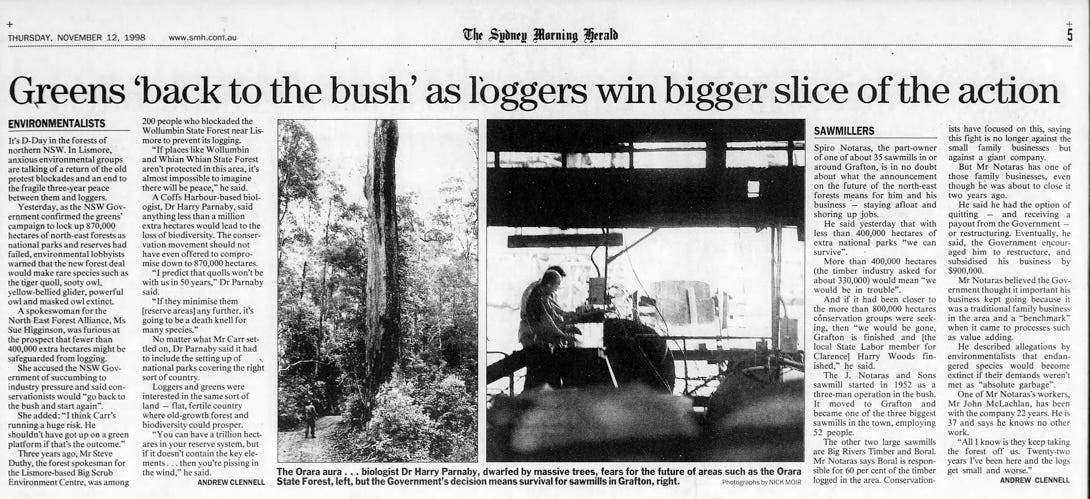

In Australia, an era of organised logging blockades began in the Nightcap range of northern New South Wales in 1979, with established hammock camps high up in the canopy as the last line of defence. Despite protestors warning loggers that people were in the forest and in the trees, tree-felling continued, and in the path of advancing machines, massive trees dropped amongst the protestors led to some near-misses. Stymied, the group retreated and some resorted to stealthier activity, sawing felled logs into unusable pieces, and "spiked trees with nails to deter cutting and identified them with spray paint" (Green Fire, Ian Cohen, 1996). Nan Nicholson referred to such tactics as "the most questionable act, and that which lost us most public support, actually saved the day." Destructive practices such as tree-spiking and cabling trees polarised the environmental community, yet brought awareness that continued logging of the area would likely lead to dire consequences, and a logging moratorium was declared.1

Australia and the United States have shared heritage in progressive environmental policies, but in the 1980s, so-called "extreme activism" traveled different paths. Both countries established their national park systems in the 1870s, and over the following century, both countries continued to legislate increasing protection for the natural environment. Whereas the USA passed the Wilderness Act in 1964 to protect large tracts of undeveloped land, Australia welcomed the global recognition that UNESCO's 1972 World Heritage Convention provided to preserve natural sites from ongoing degradation, among other modern environmental policies.

But with a global energy crisis in full swing in the 1970s, the political appetite for further environmental conservation legislation was on the wane, and the rapid conversion of unprotected wilderness to “productive land” accelerated with the development of ever-mightier industrial machines, like the globally exported Caterpillar D10 tractor introduced in 1977. The effective tactics of the previous era by major environmental groups swayed the tide of preservation with simple public exposure and argument, such as the Sierra Club's full-page challenge in the New York Times in 1966 to protest more Grand Canyon dams, "Should we also flood the Sistine Chapel so tourists can get nearer the ceiling?" But in the 1970s, these kinds of campaigns were less effective in generating the public and political will for sensible land management. And as the extraction industries pushed into ever-more remote and rugged wilderness, concerned activists developed new strategies to shine a public light on the ongoing devastation of majestic and irreplaceable wild ecosystems.

In the southwest USA, Edward Abbey famously inspired activists to employ means of sabotage of wilderness-destroying machinery to slow progress, such as the shearing of bulldozer hydraulic lines, dumping sand in oil and fuel tanks, and other means of temporarily and permanently disabling industrial equipment. The practice became known as "monkeywrenching" or “nightwork”, and the general rule was that violence was not to be directed at people, but machinery and infrastructure were fair game. The use of explosives was mostly fantasized, such as the only way to bring down the hated dam that flooded Glen Canyon, as the potential harm to humans could not be eliminated. Human vs. machine monkeywrenching was popularised by some American environmental groups, such as Earth First! and other groups actioning even more violent tactics, and would continue for decades in America's environmental battles. In the 1990s, actual 'eco-terrorism' was rare, but real in the United States, polarising ecologists in their level of acceptance, and ultimately ineffective in the broader environmental agenda of preservation.2

For environmental activists in Australia, the transition to non-destructive and non-violent protest methods was swifter and earlier, and by the early 1980s, "conservation organisations disassociated themselves from the political futility and ethical emptiness of violent protest" (L.J. Christensen, The Re-Enchanted forest, Murdoch University, Australia, 2005). 3

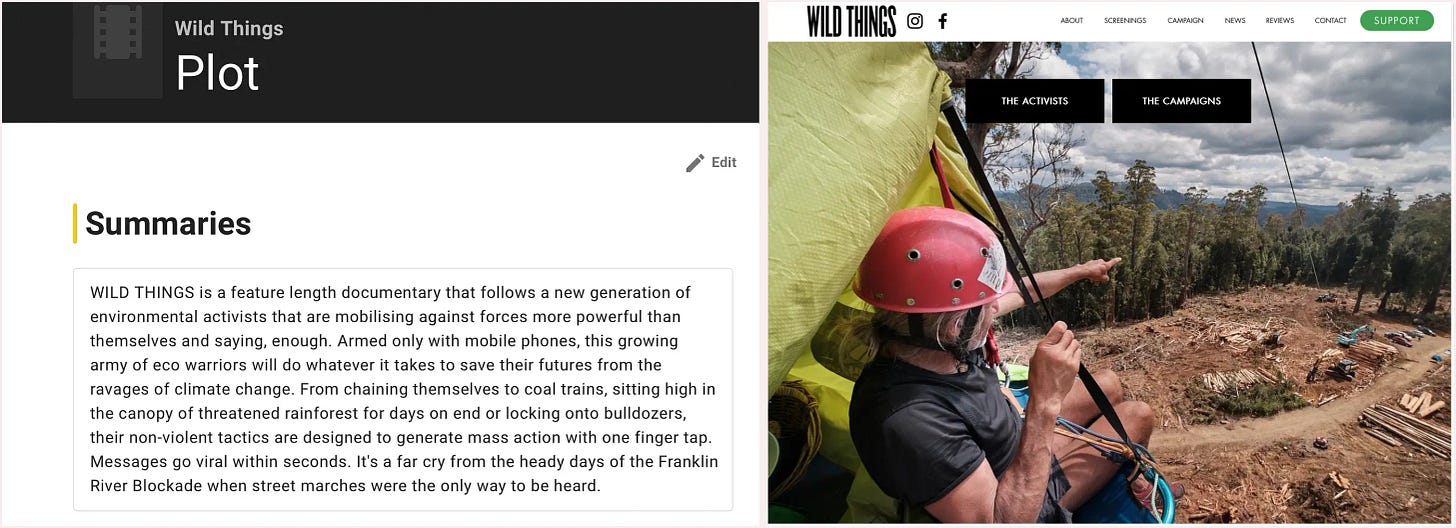

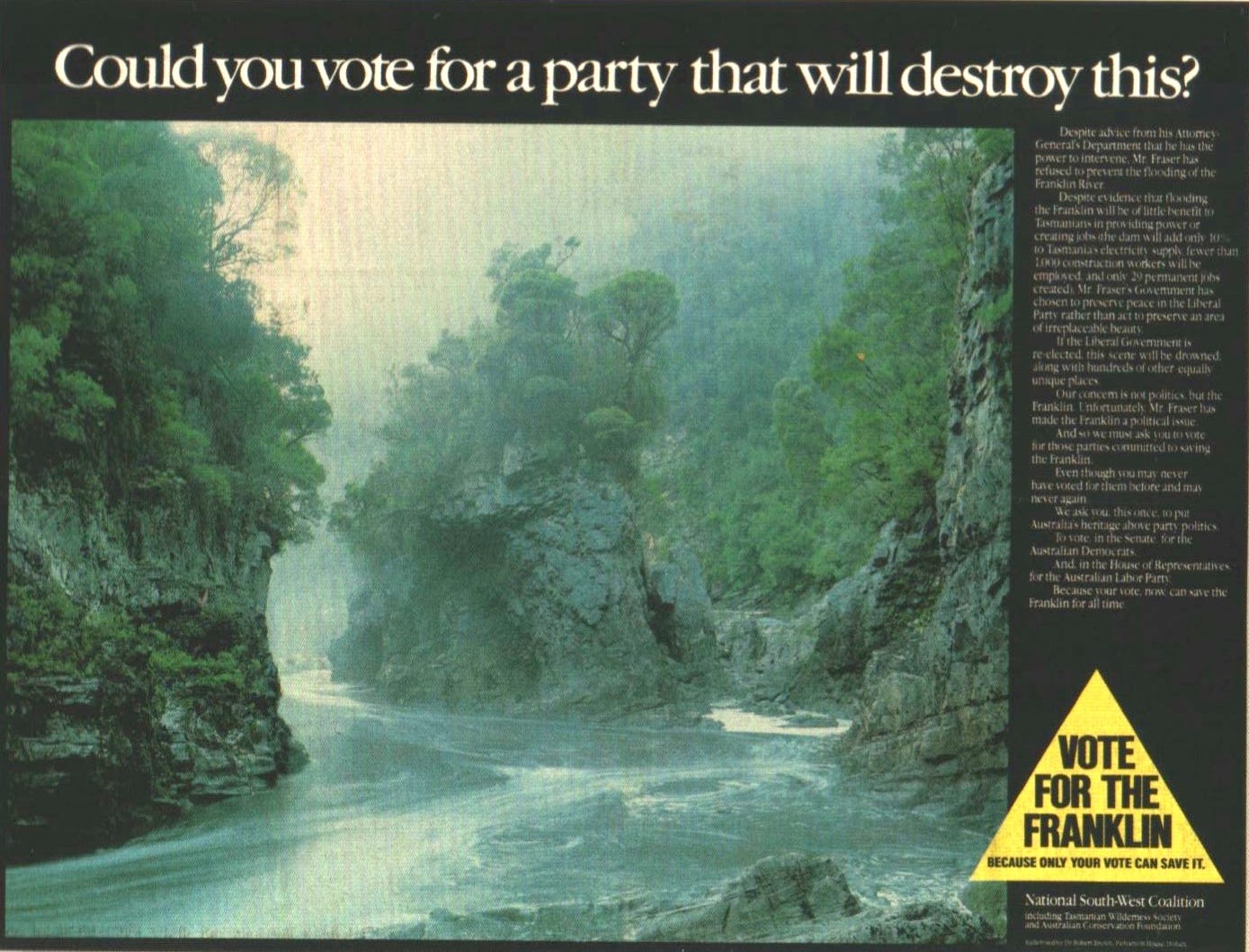

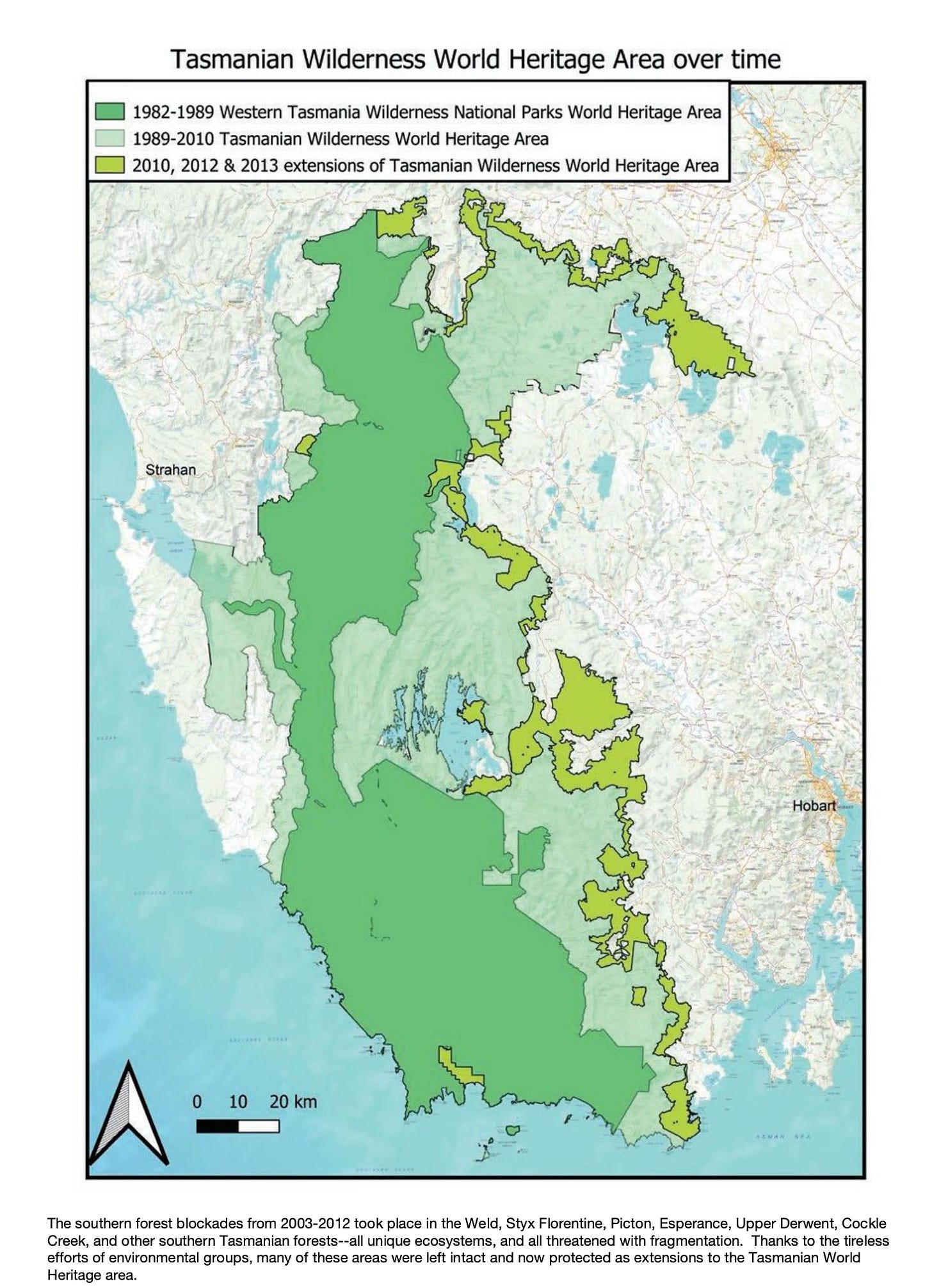

Amongst the groups peacefully protesting and risking arrest for the Australian wilds, ecotage tactics were purposely abandoned and alternate strategies of non-violent direct action (NVDA) were pursued, as long as there were mechanisms in place that ensured that protestors’ lives were not recklessly endangered, as they had been in the 1979 Terania protest. Campaigns were organised with police liaisons, compulsory NVDA training, and organised control of protesting sites and media exposure. The three-month blockade that began on December 14, 1982, and interrupted the relentless damming of Tasmania’s treasured wild and scenic rivers was a cumulation of a seven-year strategy that began with the establishment of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society and ended with a new World Heritage Site and protection of the Franklin River, a unique wild-river ecosystem.

Unlike in the USA where a ‘radical environmentalist’ connoted a stealthy outlaw disabling machinery in the dark of the night, in Tasmania, it referred to those who could create a community in rainforest conditions. As Ian Cohen writes, "At best the radicals were a powerful extreme wing of the environmental movement, prepared to undertake tasks and survive for long periods in conditions which saw moderates head home after a few weeks." During the Franklin Blockade, there were over 1200 arrests of people impeding access to key sites, often in fierce west coast Tasmania conditions.4

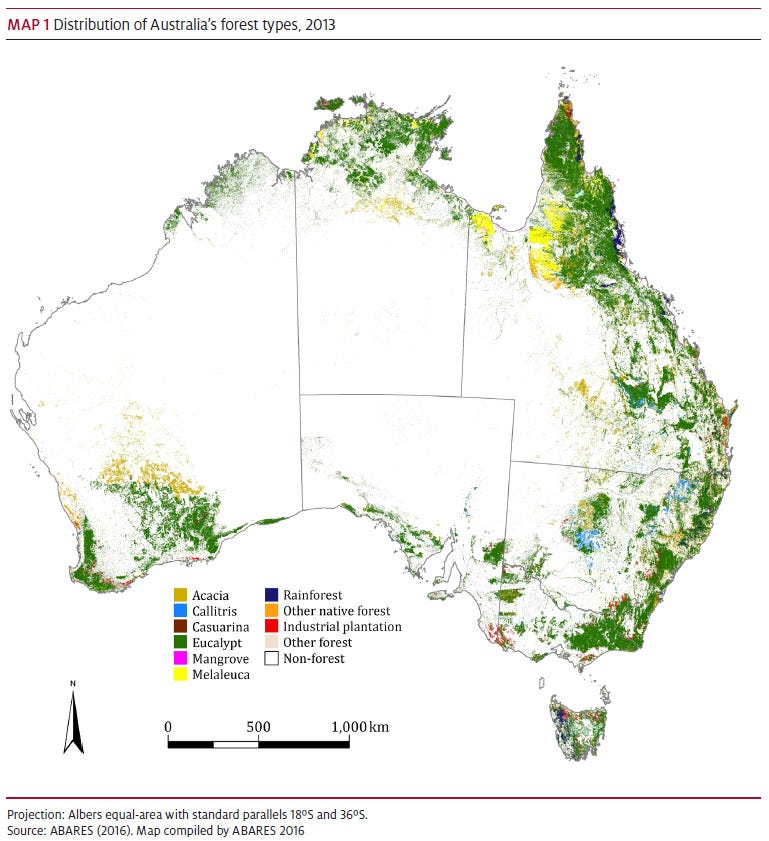

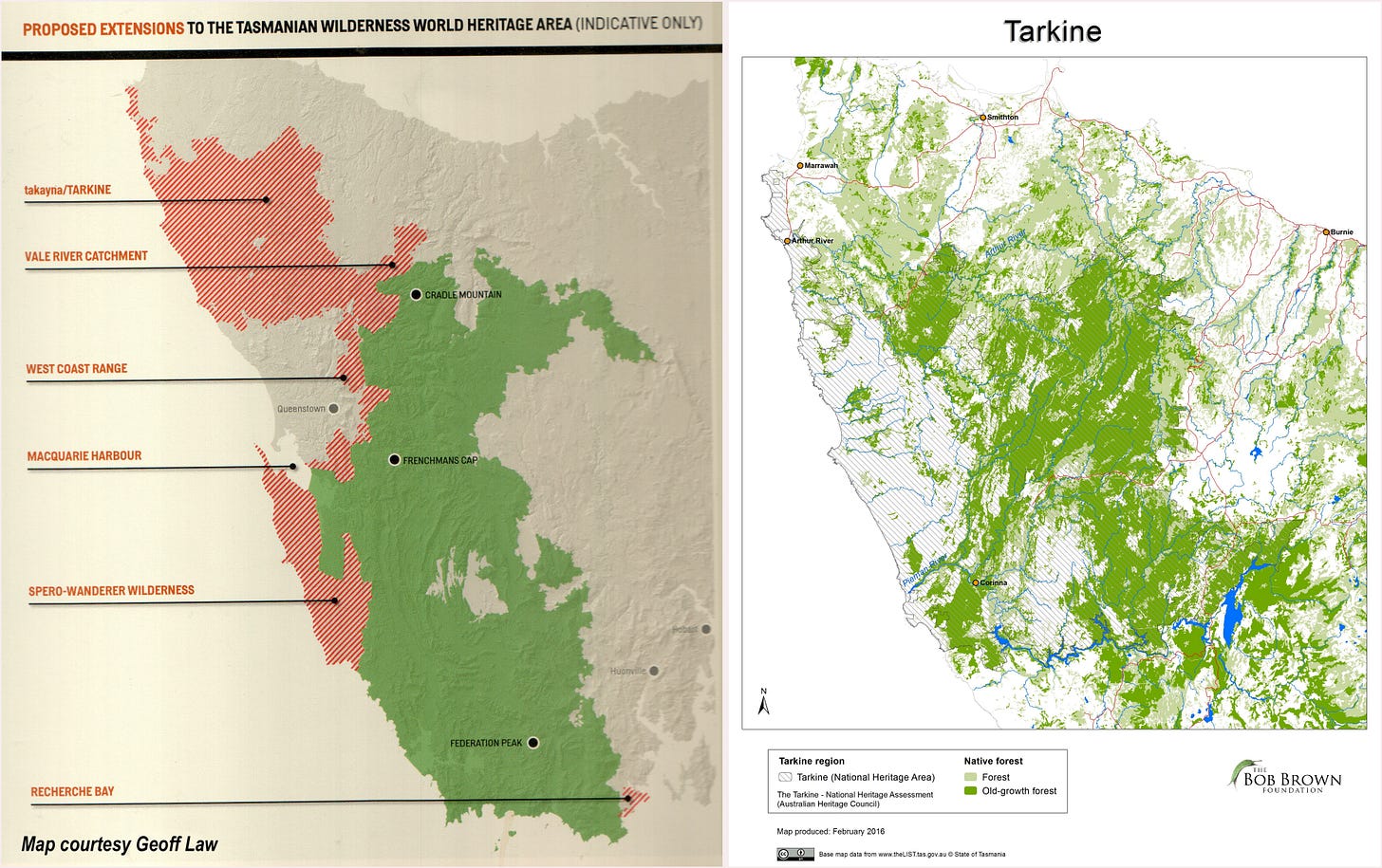

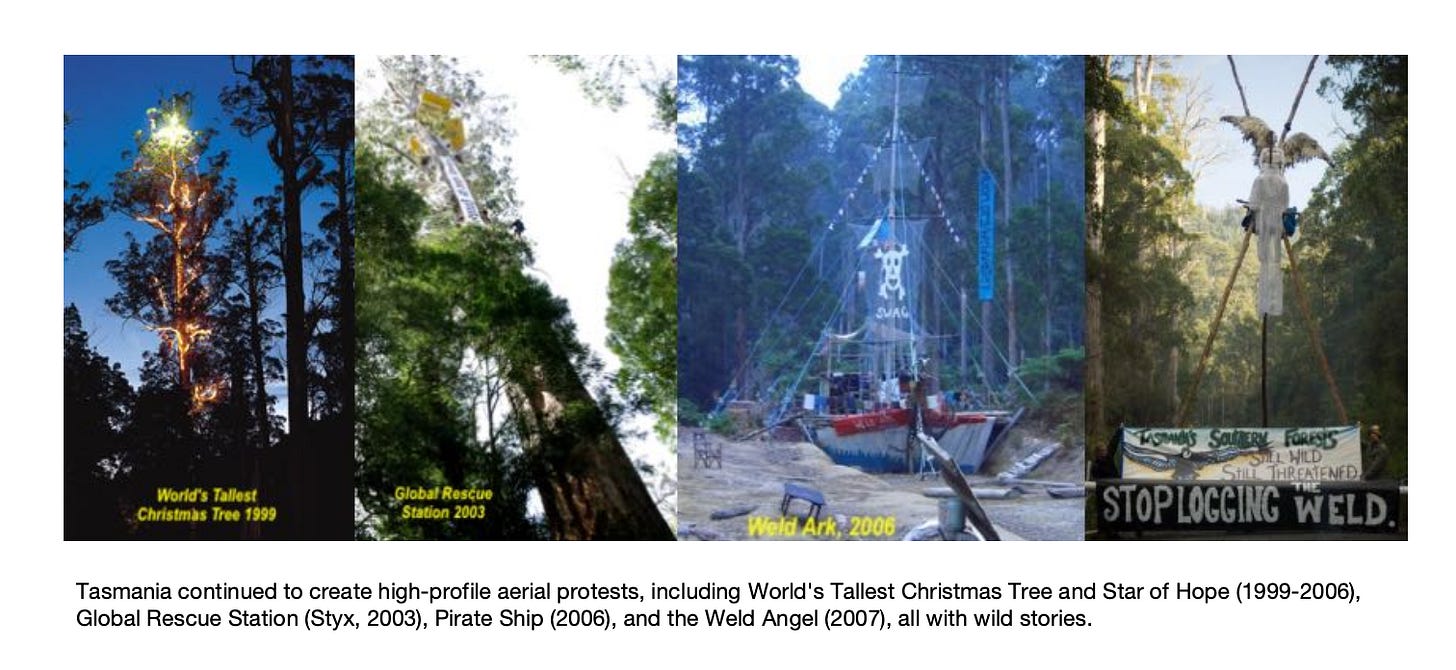

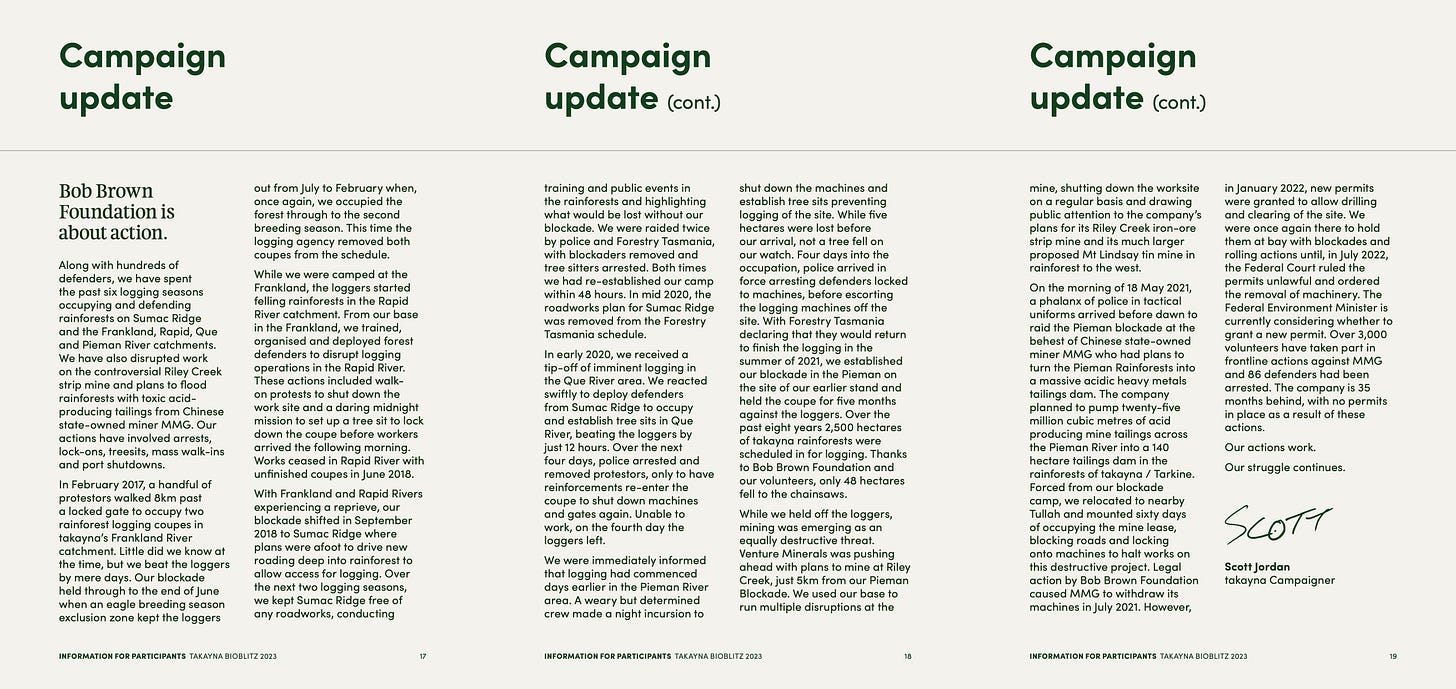

After the Franklin River blockade, the next target for the Tasmanian NVDA activists was to stall the ongoing conversion of native wet and dry eucalypt forests into woodchip plantations, especially in the threatened forests within the proposed extensions to the World Heritage area. TO BE CONTINUED.

—The history of Tasmanian NVDA Aerial Activism is the next article in this series, submitted to Wild Magazine and due for their winter publication.

FOOTNOTES

Adam Burling comments, "Tree spiking is folklore in Australia. Either used by industry to bash environmentalists in media or spoken in bravado by activists who want to claim they are more radical than others," and that John Seed asserts that there wasn't any spiking of trees at all in Terania. Bob Burton adds, “As far as I know there has never been an instance of tree spiking/sabotage by environmentalists against the logging industry in Tas (and I have investigated a lot of industry claims about specific instances). That created a problem for the industry -- Tassie activists were too much into peaceful protest -- so some in their ranks sought to create a lot of hype about Earth First/sabotage/tree spiking etc. They did this for a few reasons: it undercuts the development of broad public support for forest protection, allows the industry to get close to police and mobilise the "anti-terrorism" arm against activists, makes it easier for the industry and police to conflate peaceful protest with terrorism, and also was used to justify violence against environmentalists.”

The three editions of Earth First's Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching (1985, 1987, and 1990) were focused on destructive protest tactics. The 1997 Earth First! Direct Action Manual advocates non-destructive methods, and emphasises safety and peaceful contact with authorities during actions. In the USA, activists like Judi Bari led American campaigns that advanced peaceful actions to effectively slow and stop the destruction of natural spaces, incorporating music into daytime human blockades, rather than destruction in the dark of the night. Despite being a known non-violent activist, Judi Bari was nearly assassinated with a motion sensor bomb placed in her car in 1990, and then framed for making the bomb(Bari was later vindicated and the city of Oakland now commemorates May 24—the day of the attempted murder—as Judi Bari Day. Though monkeywrenching and ecotage practitioners captured the public’s attention (popularly merged with outlaw legends), actions that involved destructive means were often were broadcast in the news, but as a long term strategy, failed to gain broad public support, as any act of civil disobedience, no matter how trivial, was widely framed as “eco-terrorism” performed by “radical environmental organizations”. For example, in an environmental theatre event to expose the scale of the redwood trees logged in California, a giant stump of a recently cut tree was delivered to a congressman’s office—the act was noted in the records as perpetrated by “terrorists and criminals” and was likened to the delivery of a bomb. Source: June 9, 1998, ACTS OF ECOTERRORISM BY RADICAL ENVIRONMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS SUBCOMMITTEE ON CRIME HEARINGS IN THE US HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.

The context for this quote is from a conflict inspired a singular act of violence on July 19th, 1976, when John Robert Chester and Michael David Haabjoern attempted to blow up the old growth woodchip terminal in Bunbury. Chester and Haabjoern’s actions resulted in them being sentenced to seven years in prison. These actions crystallised the Campaign to Save Native Forests (CSNF) interest in non-violent, direct action. L.J. Christensen, The Re-Enchanted Forest, Murdoch University, Australia, 2005.

The Nightcap Action Group joined the Franklin blockade and were primarily in the deepest upriver regions of the campaign. Jill McColloch recalls the timing of their upriver blockade (prior to the finish of the Uni term) as critical to the campaign, as “without them, we wouldn’t have been able to start as soon as we did.” In his book, Green Fire, Ian Cohen describes the 'love hearts' action, where crepe-paper chains of hearts were stealthily wrapped around guarded industrial equipment on Valentine's Day in 1983, signalling the message of potential ability of ecotage ("Our message was clear. 'You fear us and accuse of of eco-terrorism. We could sabotage. We have the ability but choose not to."). Of the police reaction to Franklin, Cohen writes, "For many of them it was an 'other worldly experience'. They had never encountered the nonviolent philosophy and accompanying forest strategies. The normally quiet backwaters of Tasmania reverberated with peaceful yet confronting communication." The subsequent Daintree blockades in Queensland are also examples of alternate strategies of cat and mouse protesting, with treesits as a core blockading tactic.

modern tactics:

John,

Much more than a gear-head, your investment in & probable contributions to Australian environmental efforts mark you as earnestly honorable. Thanks!

John is gone now. Rest in peace thank you for your enduring contribution to our environment💔