State of the Art Climbing Gear, 1976

Trango History Series

Tools—Introduction for Trango history series.

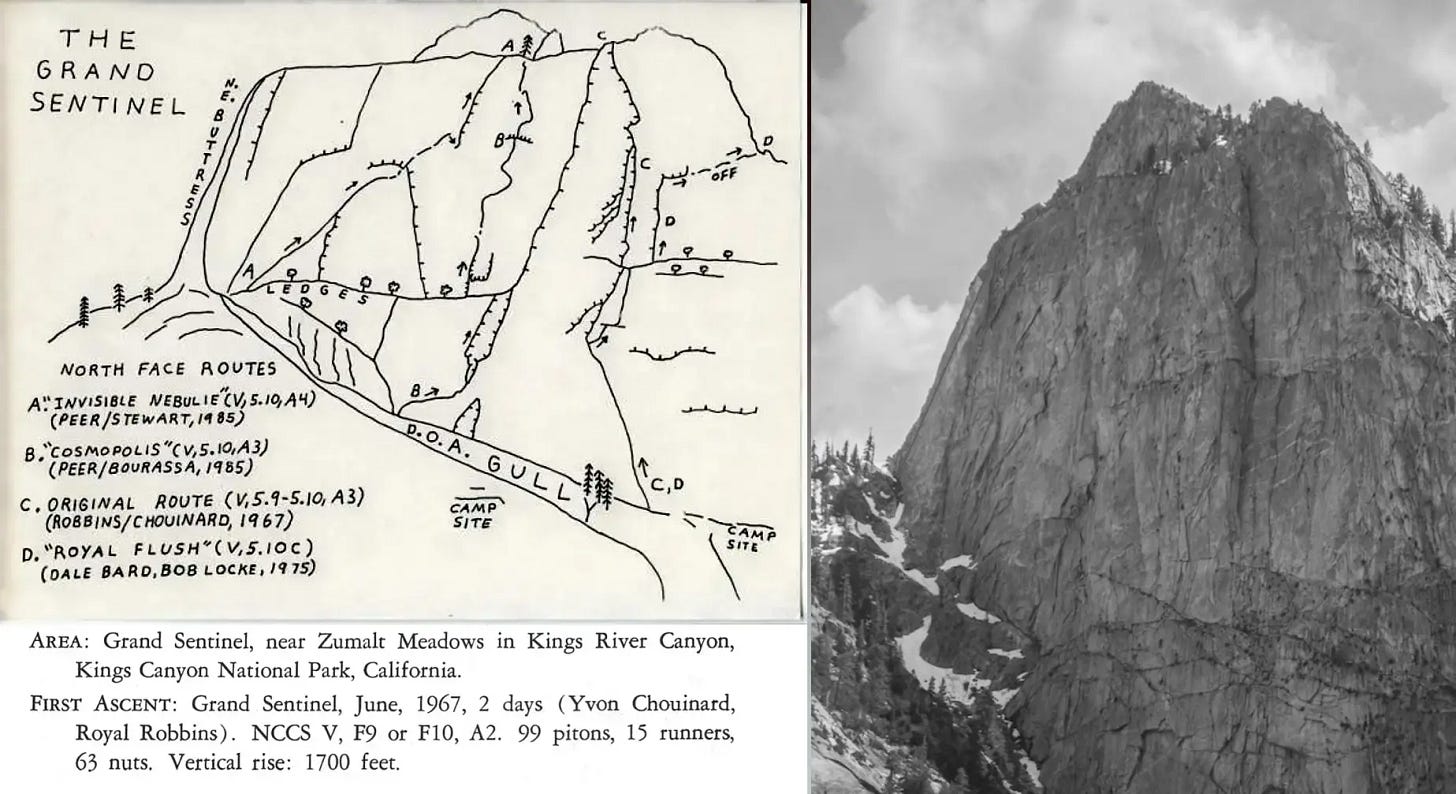

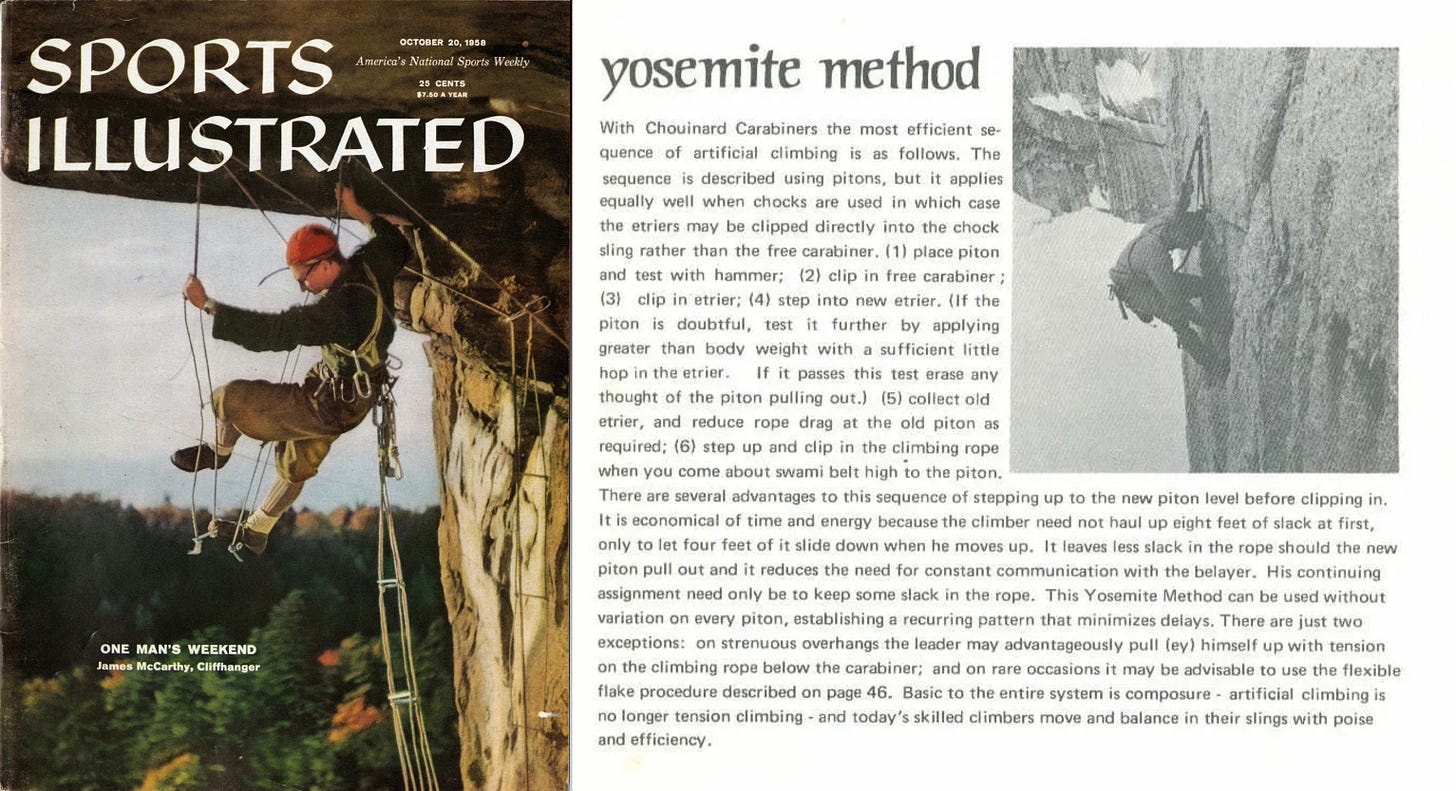

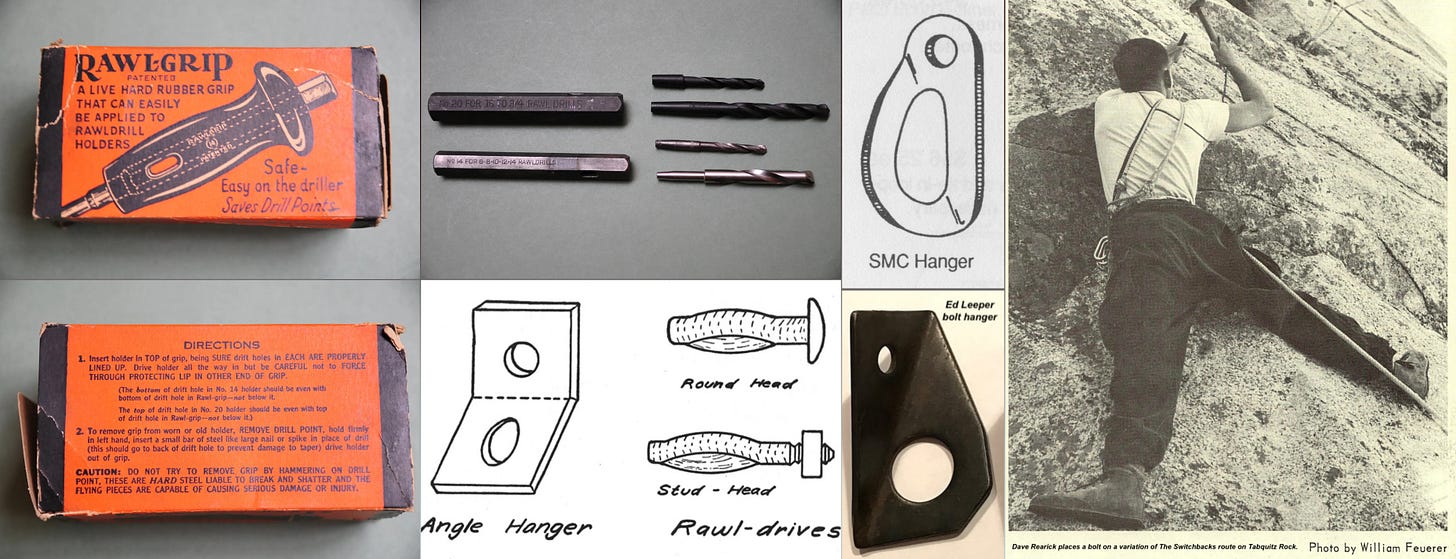

As climbing tools improved, so did the envisioning of routes up the tallest rock walls in remote mountain ranges, leading to the first ascent of Trango Tower in 1976. Let’s begin with a brief recount of the era’s equipment for first ascents in the 1970s: the pitons, ropes, bolts, strong carabiners, and clean-climbing gear. In Volumes I and II of Mechanical Advantage: Tools for the Wild Vertical (John Middendorf 2022-2023), the history of evolving climbing techniques and technology is outlined from the 19th century to the 1950s (plus a brief overview of ice gear to the 1970s) when mild steel pitons and carabiners, and natural fiber ropes were the state-of-the-art.

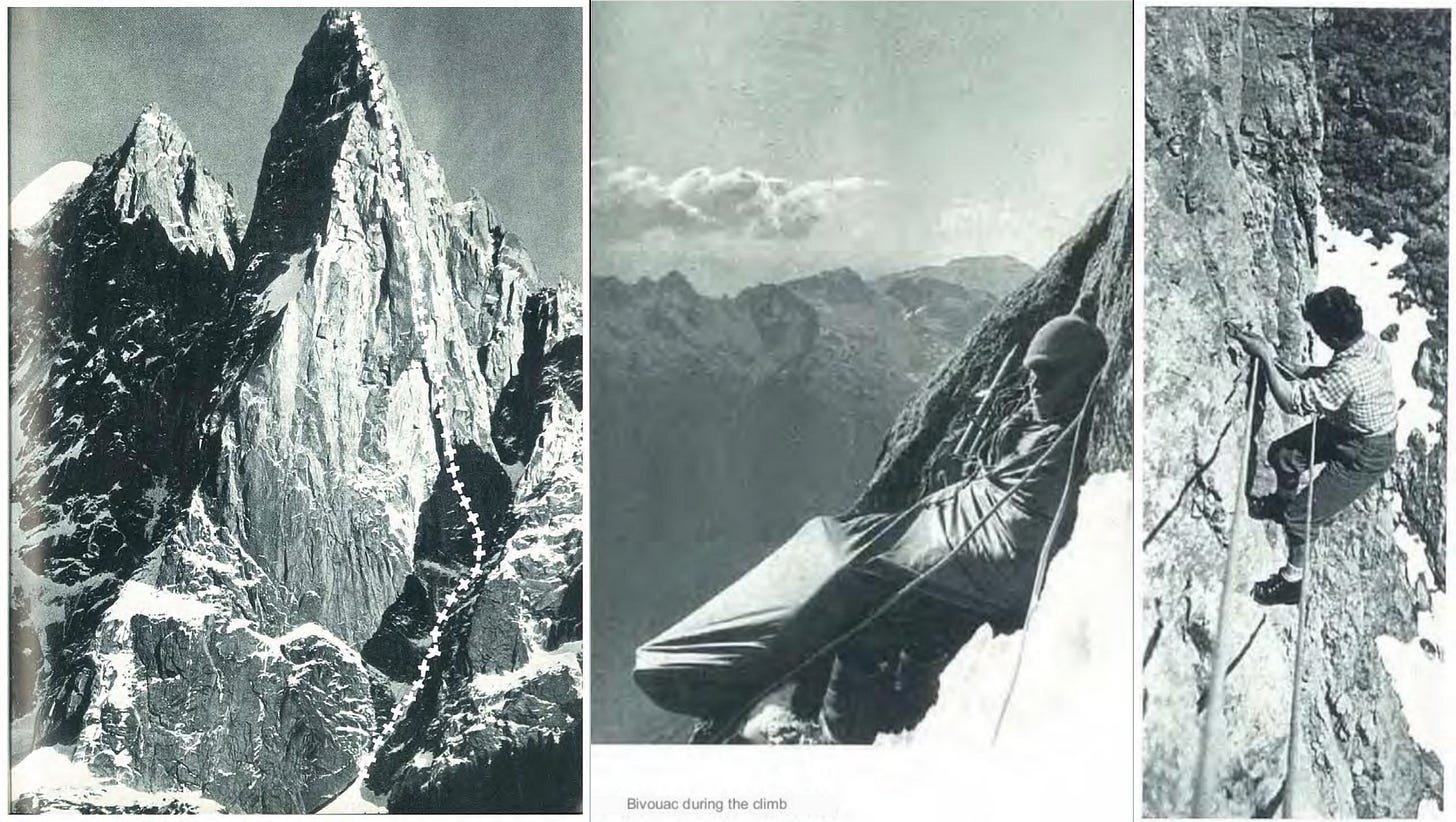

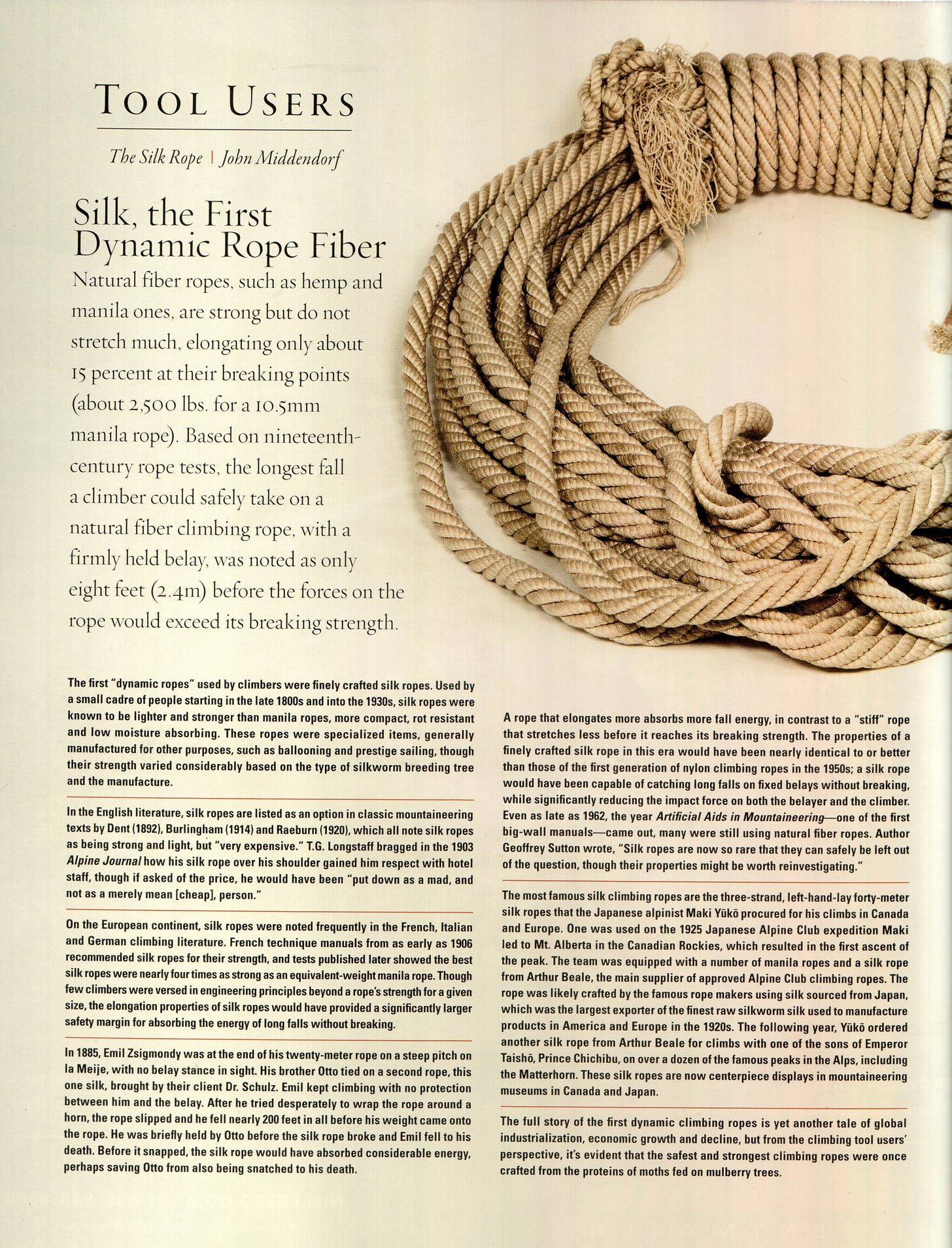

In 1955, Walter Bonatti extended the boundaries of bigwall climbing when he climbed the southwest pillar of the Dru using his “System Z” solo system, dependent on piton anchorage every twelve meters using a 36-meter rope. His 28 kilograms of equipment included 79 thin pitons, six wooden wedges for large cracks, fifteen carabiners, a dozen slings, three rope stirrups, and two hammers. The pitons and wood wedges covered thin and wide (~50mm) cracks—but not sizes in-between—and were placed and removed multiple times, with 50 pitons left in place as he ascended. Ropes were state-of-the-art: one 36m nylon rope, and one 36m silk rope. The route involved difficult snow and ice climbing, free climbing, and tenuous dependence on pitons and hammered-in wood blocks to make upward progress. Bonatti’s story of the climb in On The Heights (1964) is full of pre-climb angst and depression, followed by complete focus and technological prowess amidst great suffering and storm during six desperate days and frigid nights on the successful climb. The proof that a self-supported solo climber equipped with specialized gear could establish an elegant new climbing line on Chamonix’s tallest and sheerest cliff set a new standard and inspired others.

In 1956, ten Italian, Swiss, and French climbers repeated the route in teams of two, using the traditional double rope lead/aid system (see Volume 1, ibid). The climb was done with only pitons and without any bolts drilled into the rock, a tool that Bonatti believed carrying, even “at the bottom of a rucksack … destroys the spiritual value of a climb” and voids the meaning of the word, “impossible” (On The Heights, p.88). As bolts were added with subsequent ascents, controversies around style and the means of ascent became everpresent, but climbers’ inspiration to climb even bigger and steeper bigwalls persisted, and with it, tools and techniques evolved in the decades that followed.

Materials

The expanding availability of three new materials in the 1950s—nylon, aluminum, and high-strength steel—led to new tools and strategies for bigwall climbs. As the era progressed into the mid-1970s, lugging less heavy gear to climb bigger things safely became the trend as tools evolved. Nylon ropes were lighter and stronger, and aluminum clean gear replaced chunks of heavy piton steel. Lightweight shelter and outerwear designs had matured, proven, and optimized on the 8000m peaks, where ultralight alpine ascents with single rope and light descent gear were possible, such as Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler’s 1975 first ascent of the northwest face of Gasherbrum I (Hidden Peak) in three days.

Without going into the same detail as the Mechanical Advantage: Tools for the Wild Vertical research of the evolution of equipment and climbs for the period from 1950-1975 (which is largely covered in other literature, and weaves many international innovation threads), we’ll consider some of the major equipment developments that specifically pertain to essential tools for the bigwall climbs of the 1970s.

Pitons (Pins, Pegs)

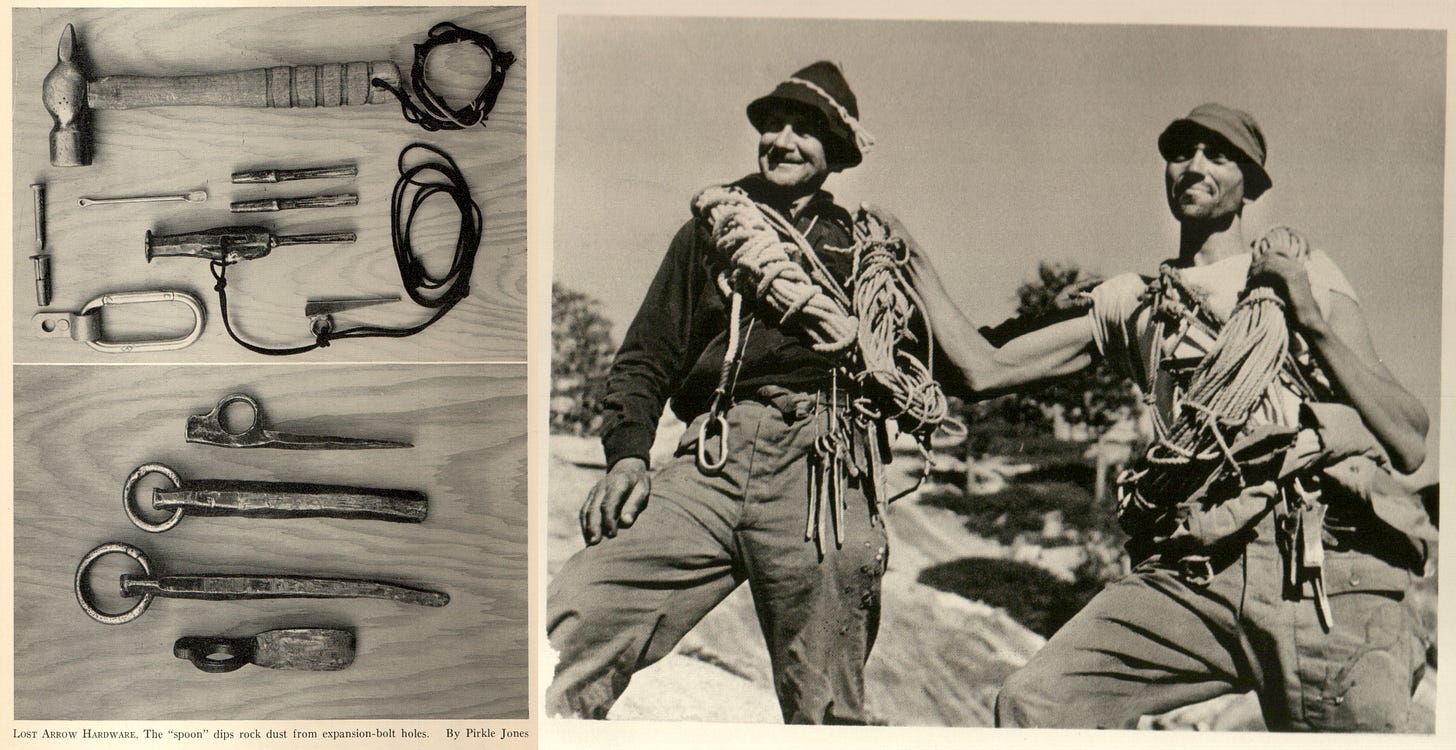

Students of Yosemite climbing history know well the moment, in the late 1940s, when the Swiss blacksmith John Salathé forged high-strength alloy steel pitons and established new routes on Lost Arrow Spire in 1947 with Anton Nelson, and the north wall of Sentinel in 1950 with Allen Steck in Yosemite Valley, two of the world’s most technical bigwalls at the time. In the 1950s, bigwalls were coming of age in North America and Europe, and the Valley climbers realized alloy steel anchoring devices completely changed the game for long routes, simply because they were tough and reusable, in contrast to softer pitons of similar designs made by most European suppliers, which would quickly mangle when repeatedly hammered in and out of cracks. (footnote)

Footnote: Technically, the European steel (NOT ‘soft-iron’) piton materials were mild steels not as hardenable as high-strength steel. ‘Softer’ in this sense means more malleable and not as hard. Many pitons made in Europe and other countries were designed to only be used a few times, then intentionally left fixed, considered a public service for the next team. With time, classic bigwall routes like those on the Tre Cima di Lavaredo in Italy became almost entirely fixed. Contrary to common wisdom, some European manufacturers, such as Charlet Moser, were also making tougher pitons in this period, they were just not as common, as for limestone climbs the softer pitons were preferred and easier to place in brittle rock. The early Fritsch pitons might also be of higher grade alloy steel. Recently Yvon Chouinard wrote to me, “You’ve done a great job with a complete history of the gear. I only have a minor comment.If you use 1010 or 1020 mild steel and heat and pound it enough times it absorbs carbon from the coal or charcoal and becomes harder. I’ve made some pitons this way and they are much superior to the usual Euro pins that were heated only once or twice. The best Euro pitons I’ve tried were hand forged by Fritsch in Switzerland. Plus, they had a good shape with wide necks which made them even stronger.” Also see this post: 1950s USA Climbing Gear notes V2

With the new tougher steel pitons, climbers could gather a few dozen alloy steel pitons, and place and remove each one a dozen or more times, enabling climbs of thousands of vertical feet of all crack sizes to be ‘nailed’, as the parlance went. Piton counts became standards in first ascent reporting; Warren Harding reported ‘about’ 675 piton placements for the 1958 first ascent of the Nose of El Capitan (plus 125 bolts); while Robbins precisely recorded 484 pitons (plus 13 bolts) placed on the first ascent of the nearby Salathé Wall in 1961.

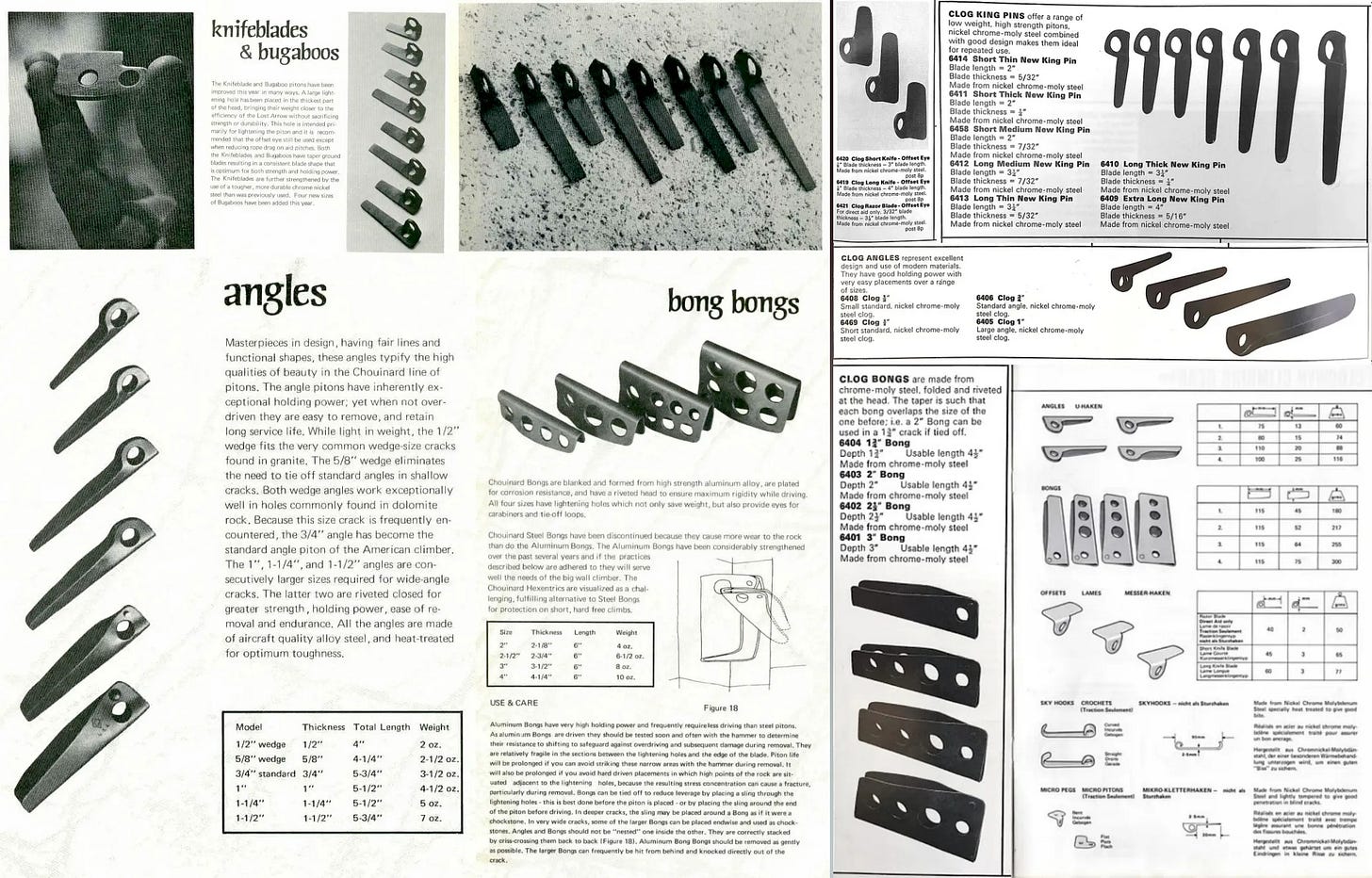

Piton Material Evolution: chrome-molybdenum steel (SAE 4130)

In the mid-1950s, 4130 alloy steel (‘chromoly’) was used almost exclusively for alloy pitons, thanks to its standard availability and wide range of heat treatability. Chuck Wilts engineered, then shared with the climbing community, the design of a thin knifeblade piton so hard it could be hammered into the thinnest granite seams, and also examined the steel’s wide range of properties for more malleable (but still tough) designs optimized for a wider range of cracks. Piton hammers from the same steel were forged and hardened a few points higher. Refinements in piton shape, particularly the taper angle, eye design, and overall length, also evolved and increased versatility.

In addition to thin pitons, larger pitons of a folded design called ‘angles’, were also made from stronger alloy steels (mild-steel angle pitons tend to flatten out when hammered into granite cracks). No longer would climbers have to tentatively depend on weak wooden blocks or hope for a thin piton crack to appear for protection, wider cracks on the walls could now be mechanically ascended with a reasonable ‘kit’. Jumping forward to 1975, a wide range of alloy steel pitons became readily available from many suppliers, ranging from hairline seams to 4” wide cracks (100mm) (footnote).

Footnote: The first alloy angle pitons were developed for the horizontal cracks of the Shawangunks in the early 1950s, and in the decade that followed, California and Colorado climbers created collections of all sizes of custom-made tough pitons with alloy steels, optimized and bashed to their maximum potential on bigwalls in the 1960s and 1970s (this history of development is well evidenced in the Karabin Climbing Museum in Phoenix, Arizona; the innovation aspects are also examined in appendix: 1950s USA Climbing Gear notes (including important material and design contributions made by Bob Owens, Bob Bruning, Norton Smithe, Chuck Wilts, Bill Feuerer, Richard Long, Jerry Gallwas, and others).

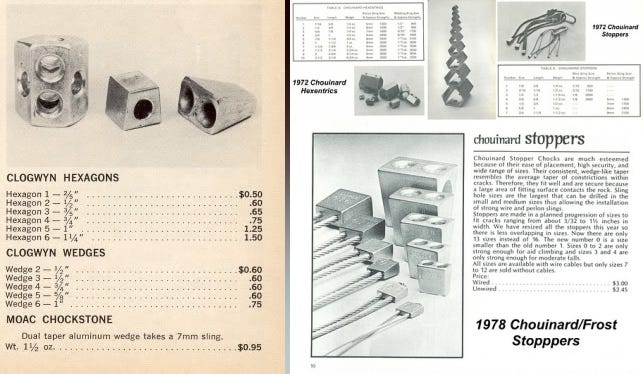

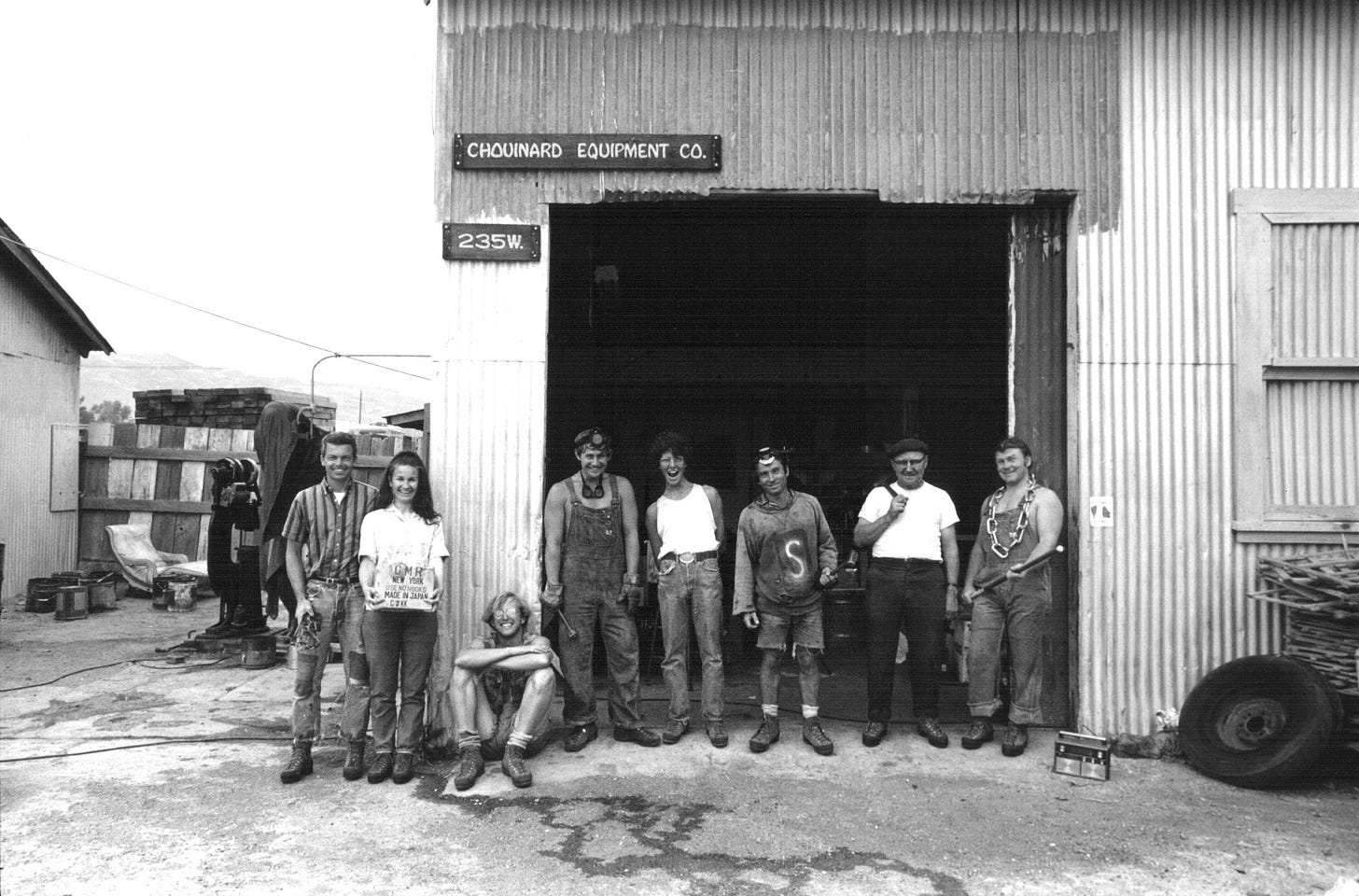

Full Sets

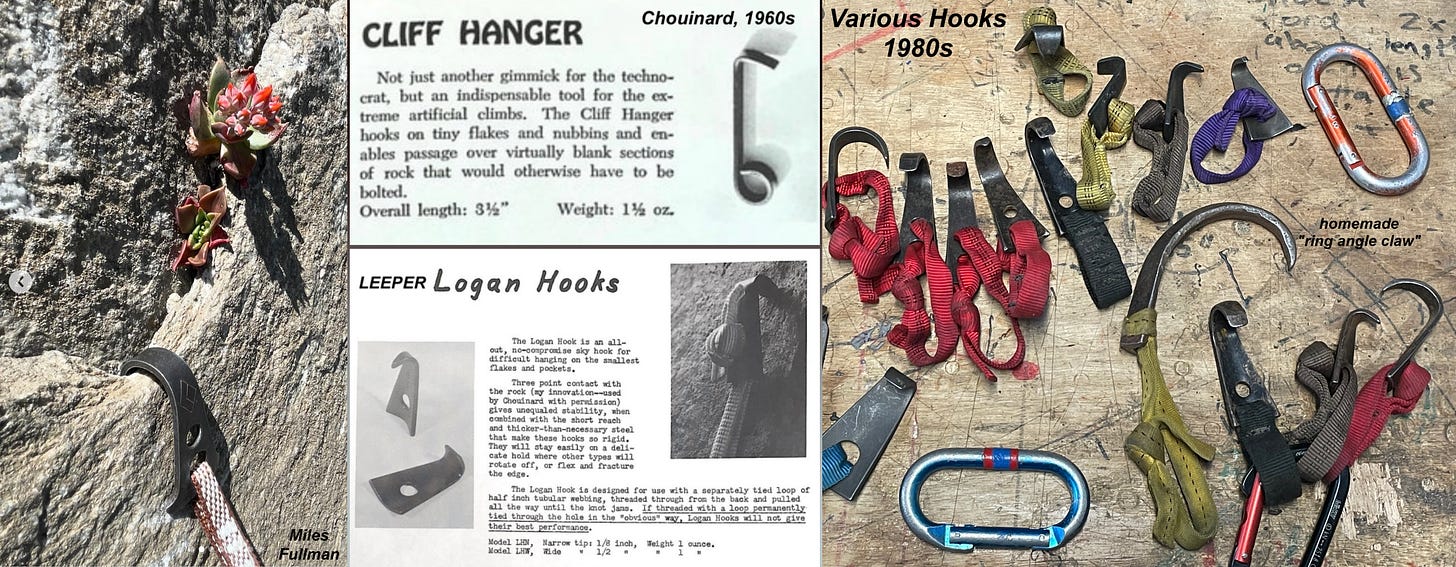

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Great Pacific Iron Works (USA), led by Yvon Chouinard and Tom Frost, produced complete sets of pitons—knifeblades, Lost Arrows, and angles (including bongs), and became the major piton supplier for the granite bigwall climbs around the world. Starting in the mid-1960s, Clogwyn (UK) was also a producer of high-quality high-strength alloy pitons, and by 1975 also offered a full range. Other manufacturers, notably Hiatt and SMC, also produced quality angle pitons and other shapes from high-strength alloys in this period.

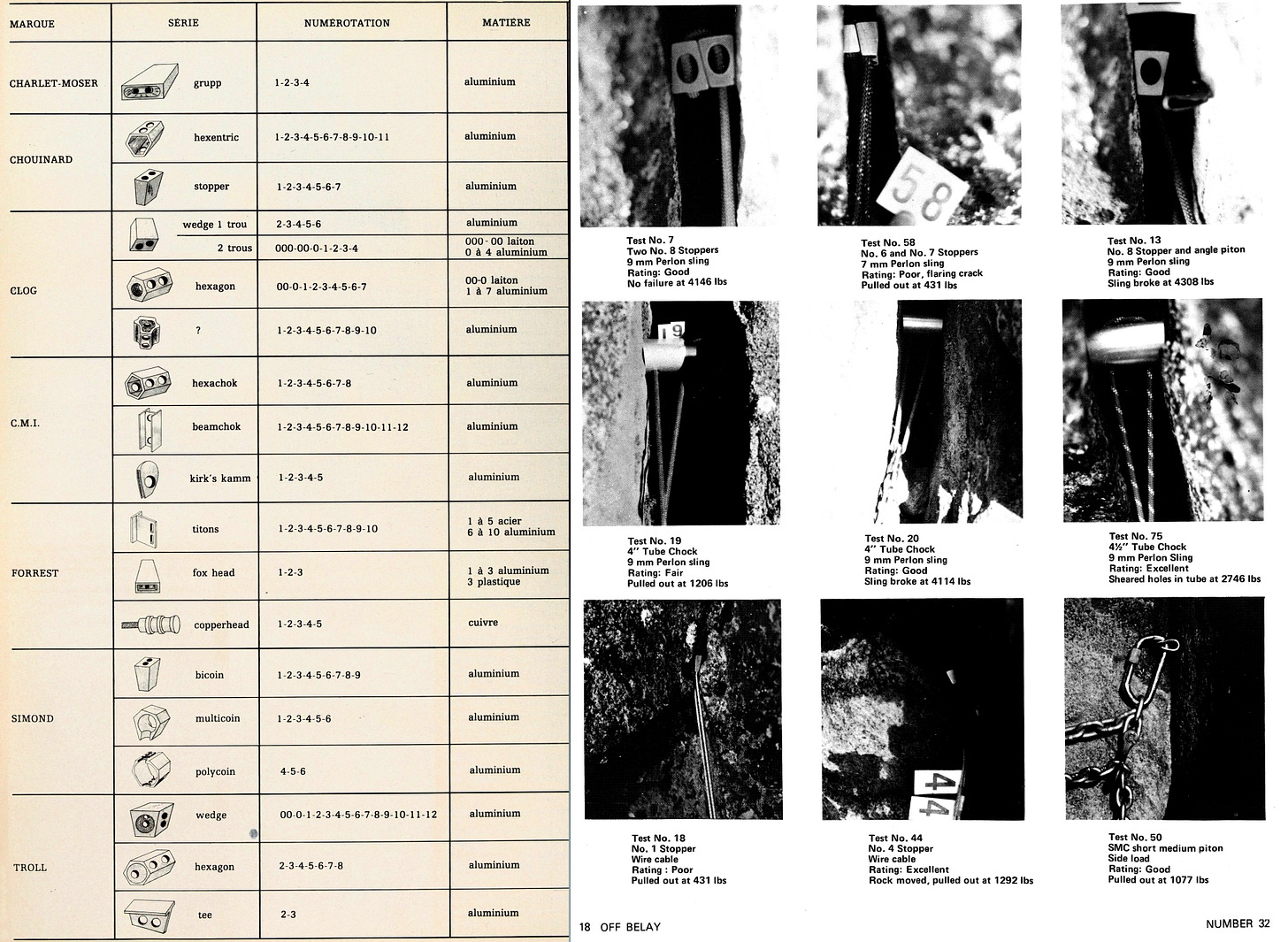

Clean Climbing Gear (Chocks, Hexagons, Wedges, Stoppers, Nuts)

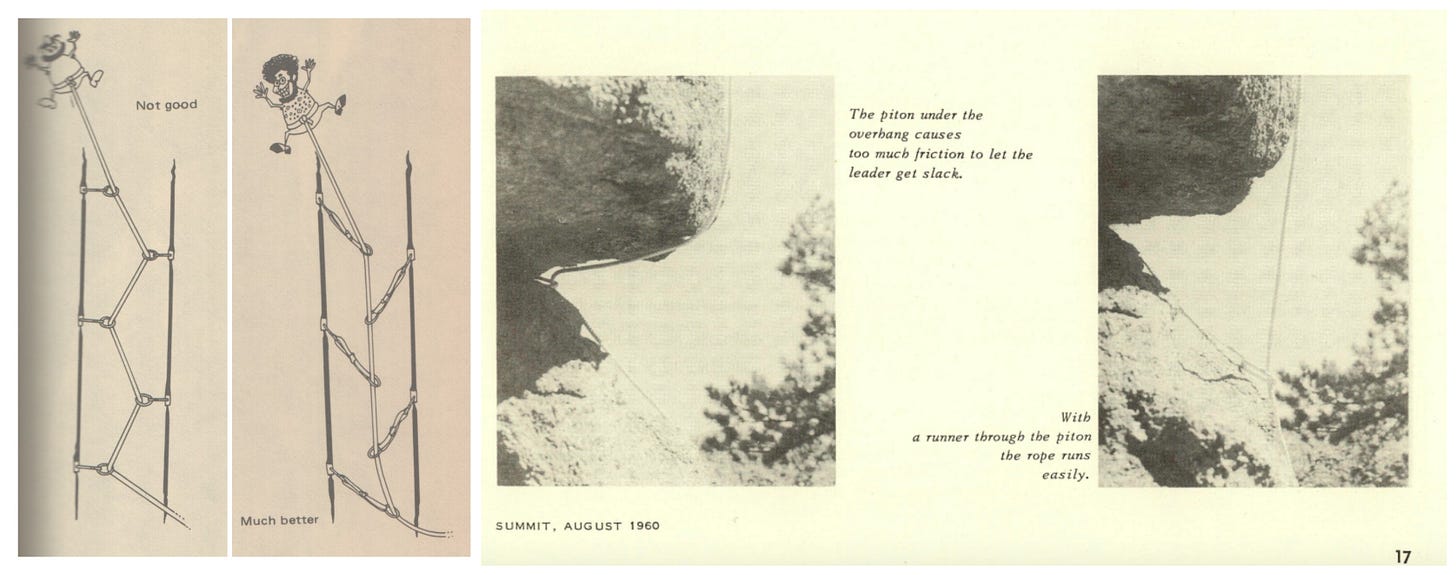

Even though British bigwall climbers adopted pitons on ‘offshore’ walls in the post-WWII era, antagonism toward piton use at home as ‘unsporting’ led to the development of points of protection that could be creatively wedged in natural cracks, a developing artform often called ‘nutcraft’, as modified machine nuts were among the earliest technology. In addition to a range of production pitons, Clogwyn also became a leading manufacturer of aluminum ‘clean-climbing’ tools in the 1960s, and these soon became essential tools for efficient bigwall climbs, quicker and less effort to place and remove as a point of security in natural fissures. Originally called “artificial chockstones”, the names and designs soon expanded, and in popular granite training grounds like Yosemite, chocks were readily adopted in response to the deep piton scarring caused by repeated placement and removal of alloy pitons on popular routes (See “Preserving the Cracks” compiled by Tom Frost, 1972 American Alpine Journal).

A hammer tap was still common in setting this gear in the days of mixed piton/chock racks, and offshoots of various designs became primarily hammered tools, such as simple copper or aluminum swages on the end of a wire loop (generically called ‘copperheads’). Optimization continued, further reducing the need for a hammer, and in 1971, Tom Frost and Yvon Chouinard started making ‘Hexentrics’, a clever patented design that allowed for each size to be useful for three different crack sizes, followed soon by seven sizes of ‘Stoppers’, which evolved to an elegant set of twelve sizes to incrementally fit cracks from 2.5mm to 32mm.

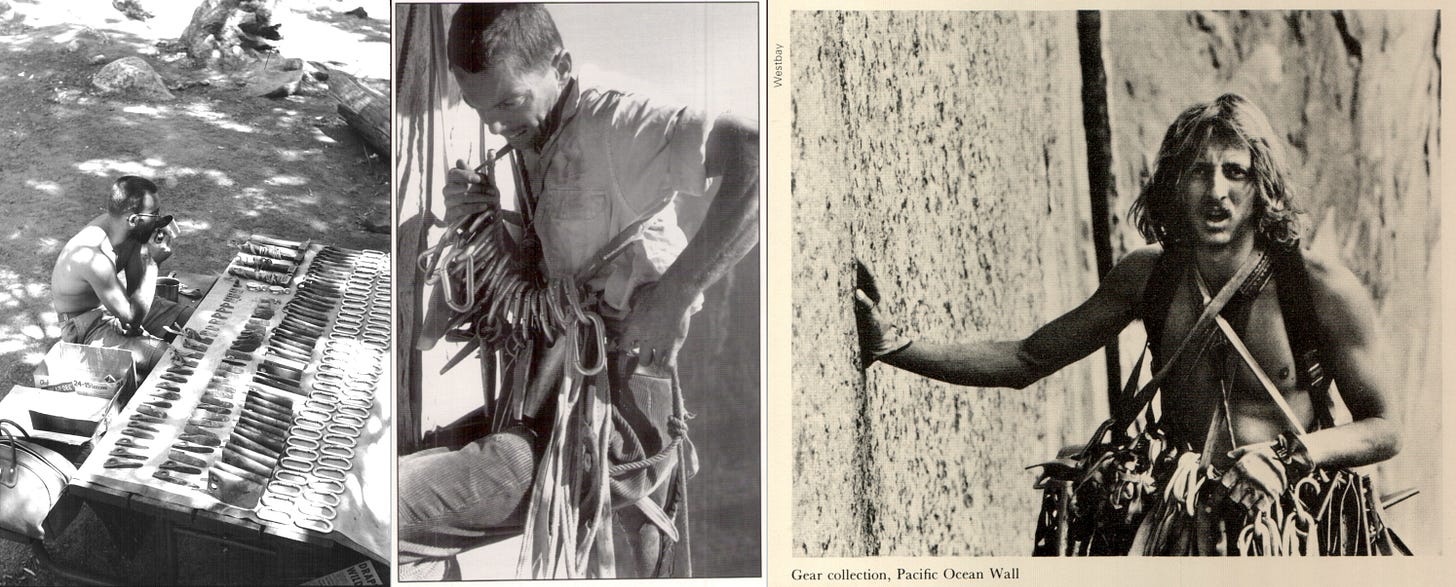

Typical 1970s Gear ‘Racks’

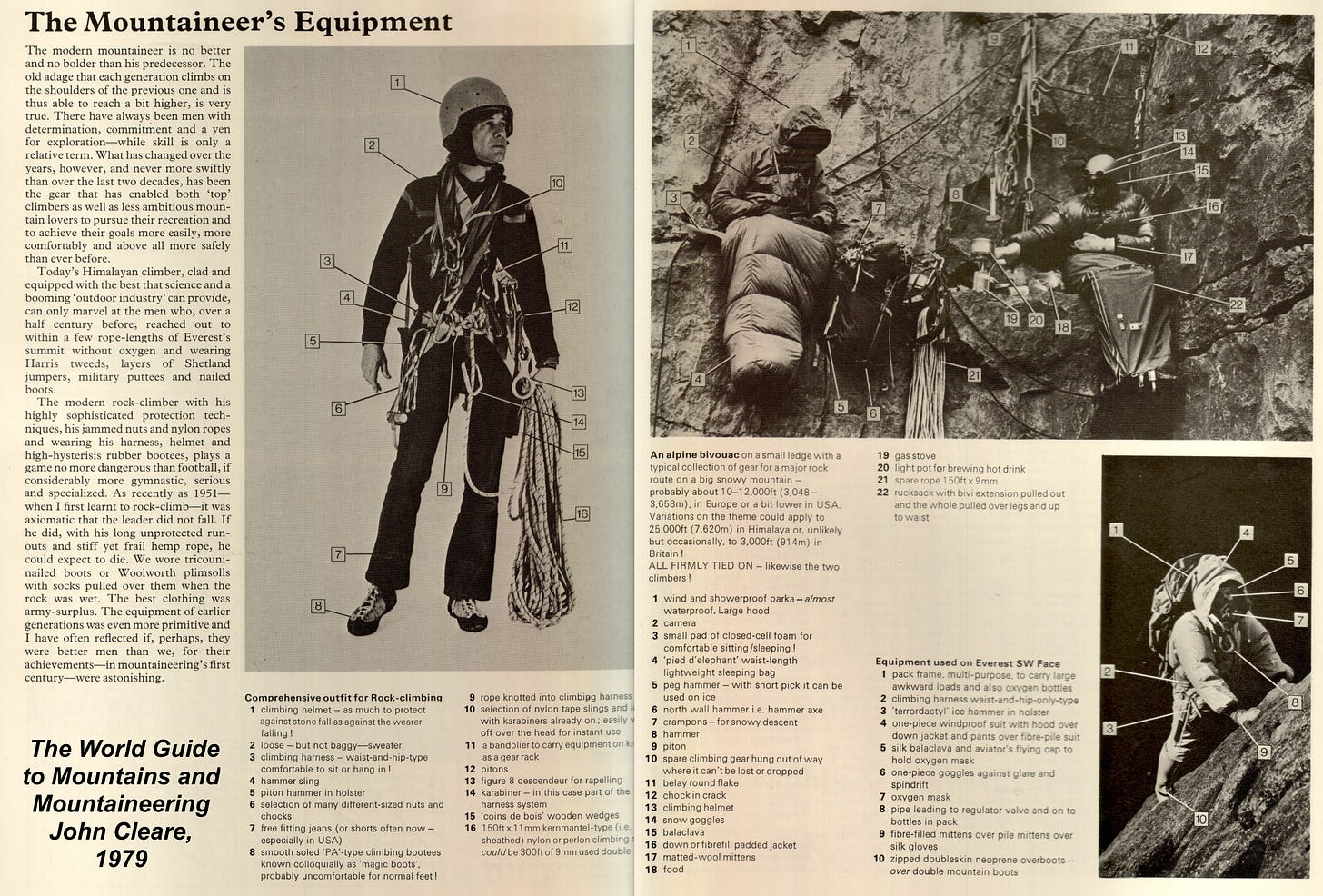

Rather than having full sets from a particular manufacturer, however, most 1970s bigwall gear racks were comprised of wired and slung chocks/nuts/stoppers of various shapes and sizes, homemade and from various manufacturers, and a mix of high-strength alloy pitons and mild steel pitons (called ‘soft-iron’). For multi-day bigwalls in the 1960s and 1970s, the typical piton rack was comprised of 45 various sizes, including one or two ‘bong bongs', a selection of chocks, at least 35 carabiners, and a dozen or more webbing slings draped over the shoulder.

Other Gear 1970s

Nylon Ropes and slings

Kernmantle ropes for climbing, with a nylon core and a sheath, designed with a balance of handling, stretch, and strength were first developed in the 1950s, and by the 1970s, had fully matured with consistent quality, though still over twice the cost of the traditional 3-ply twisted nylon ropes. By 1975, 11mm diameter kernmantle ropes had become the standard climbing rope, generally in 45m or 50m lengths, and the single lead rope technique was largely preferred for bigwall climbs over the traditional double rope systems, and with it came the plentiful use of 25mm webbing slings (aka ‘runners’ and ‘tapes’).

Aluminum Carabiners to 1970s

Steel carabiners, cheap and in plentiful supply from WW2 military surplus, were largely replaced by aluminum carabiners by the 1970s, lightening typical bigwall racks by several kilograms.

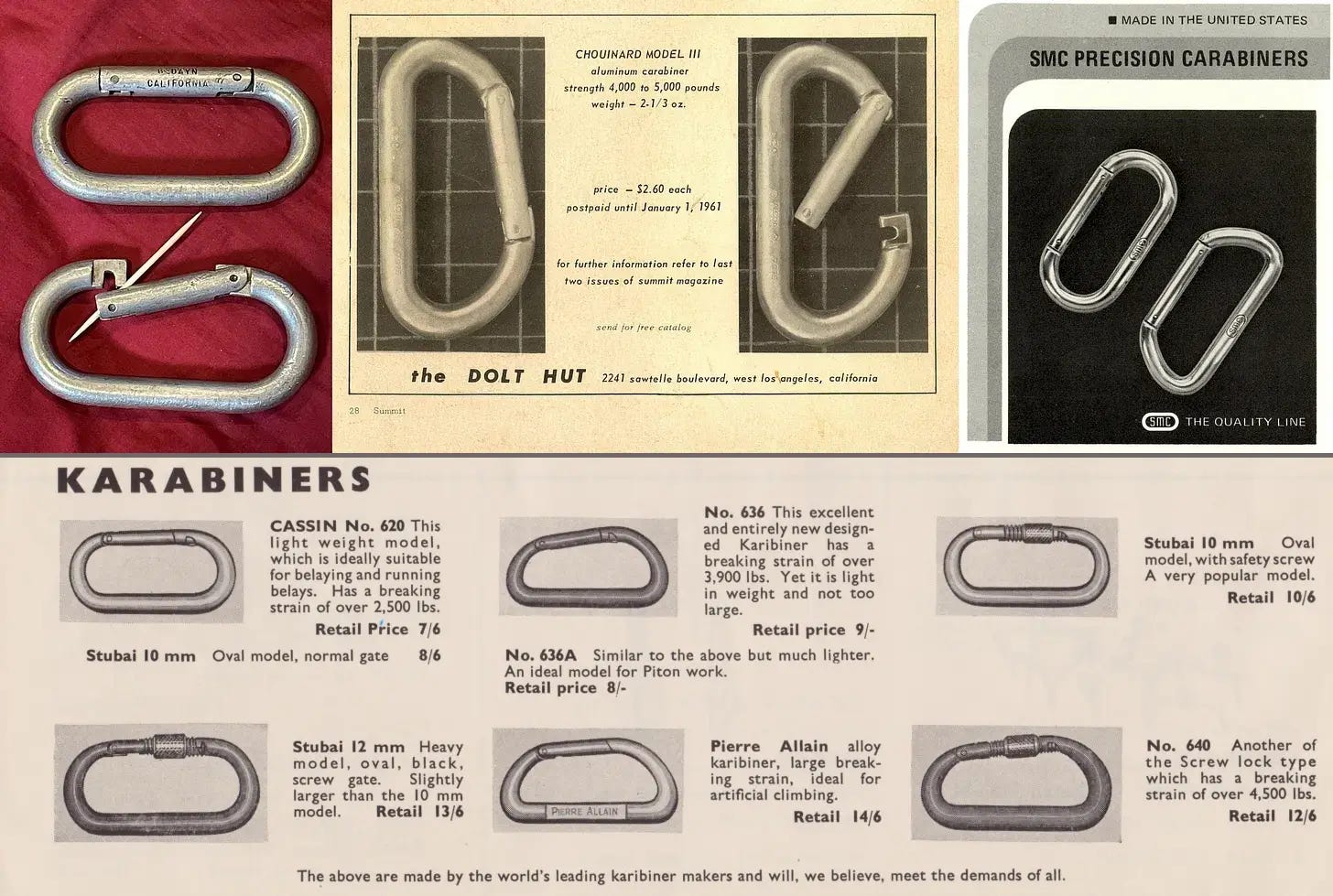

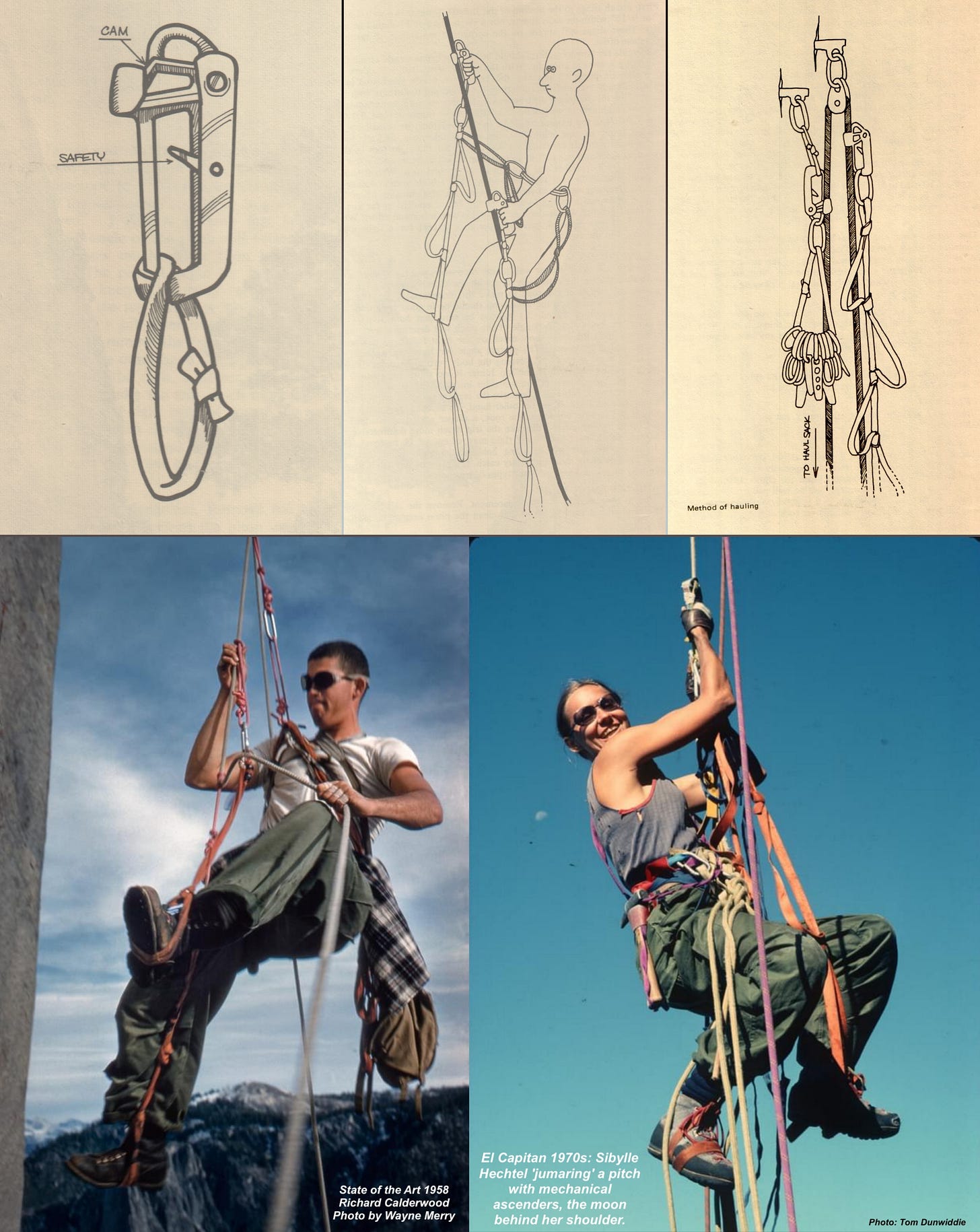

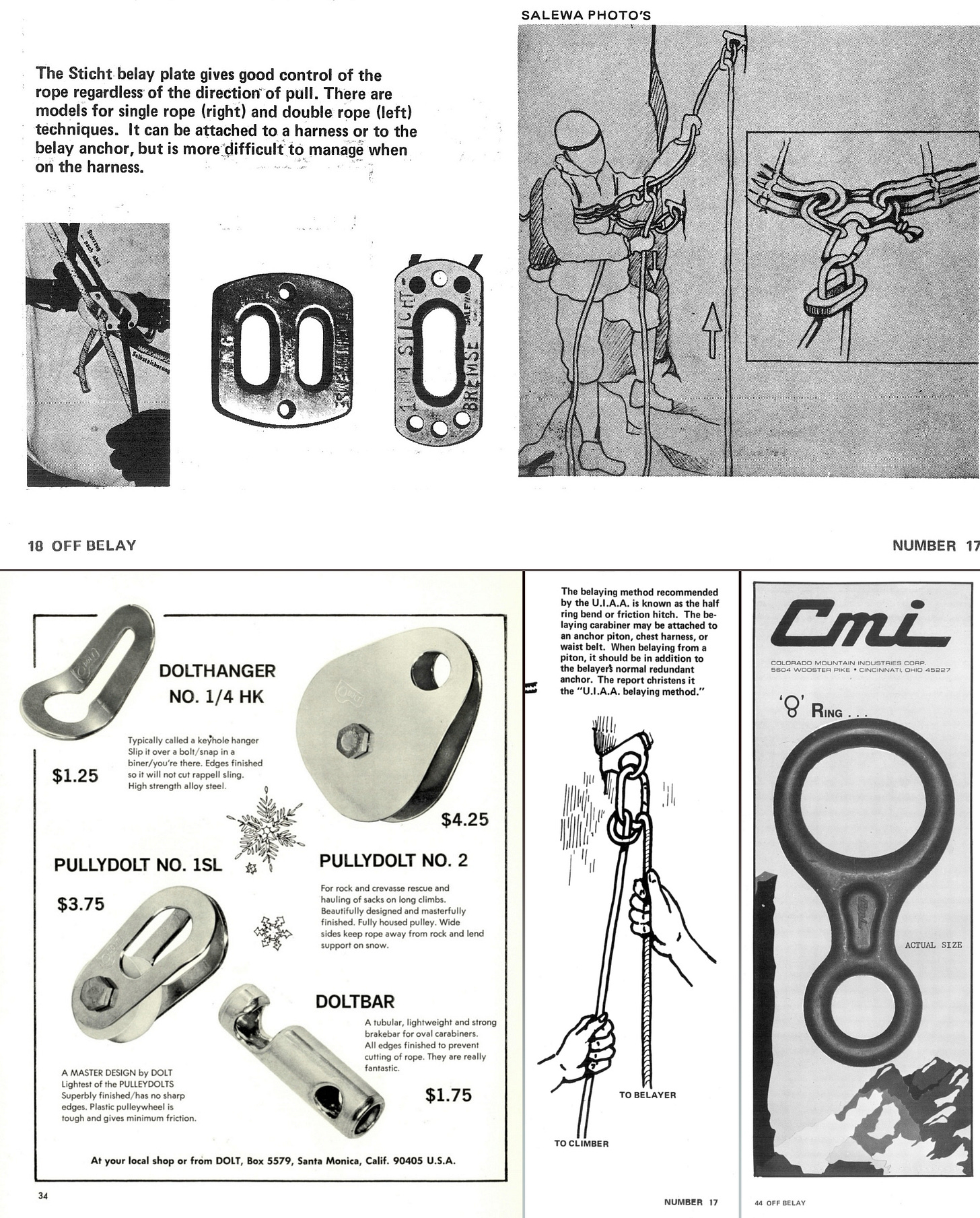

Ascenders and other hardware 1960s-1970s

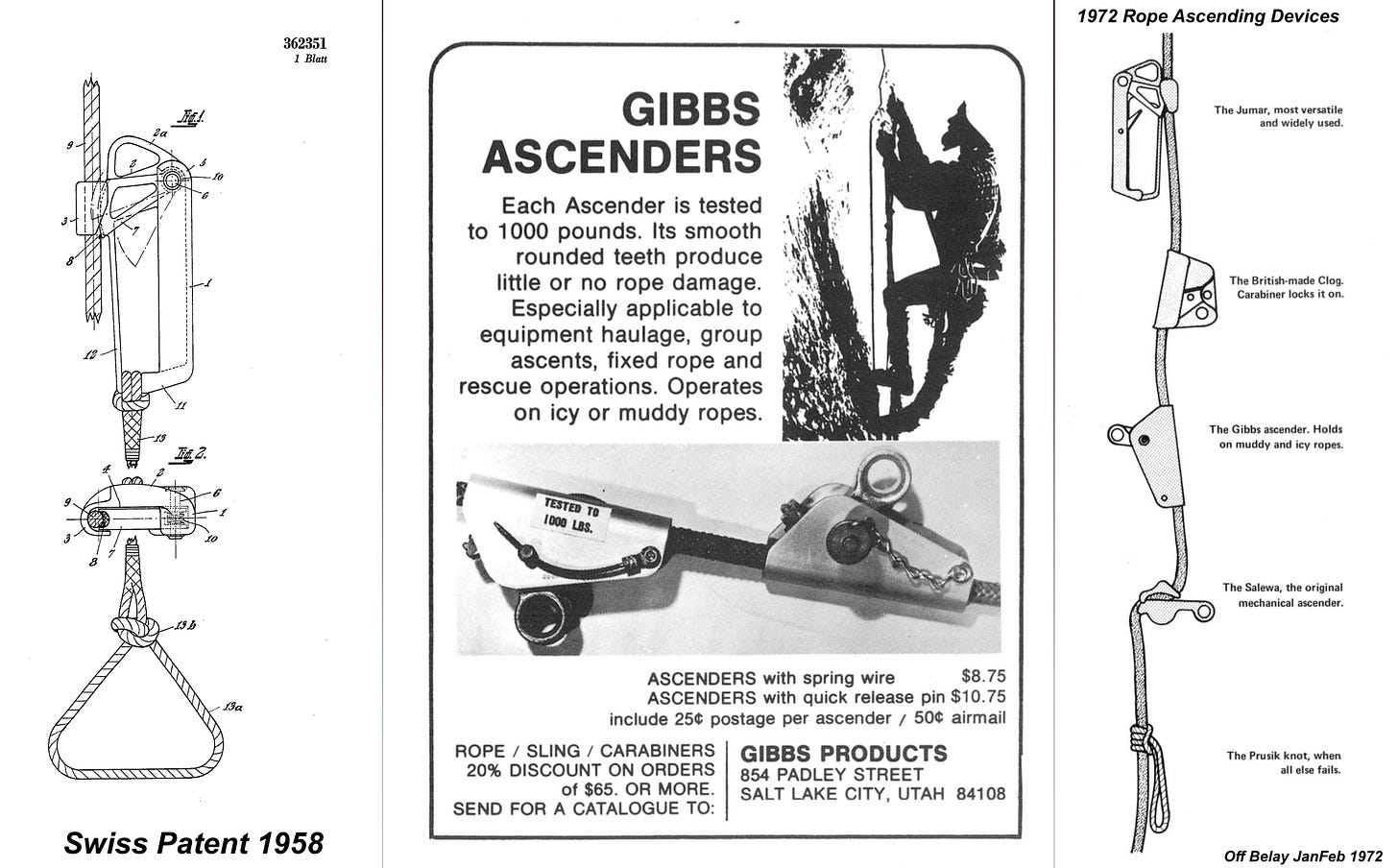

Although not the first mechanical rope clamps, the Jümar design invented by Walter Marti in 1958 in a short time replaced prusiks as the main way to ascend fixed ropes and follow pitches on bigwalls. Jim McCarthy procured his first pair of Jümars from Sporthaus Schuster in Munich in the early 1960s, and recalls, “They were not yet widely accepted in 1963, and our use of them on Proboscis (1963) could well have been the first on a big wall first ascent,” and notes that Layton Kor was also an early North American adopter (conversation with Jim, 2023). After REI began importing them in 1965, they became ubiquitous on Yosemite’s and the world’s bigwall climbs. Other brands including Clog and Gibbs were produced and preferred for certain environments, for example, the Clog design had better safety features for diagonal rope ascents, and the Gibbs design provided better grip on icy ropes.

Next: the first ascent of Nameless Tower in 1975 and 1976 (using most of these tools).

APPENDIX/Miscellanea

Techniques to 1980s here: John Middendorf’s Big Wall Tech Manual (1988)

A tiny correction to your comment "the more ideal shaped Moac, available in one size". Perhaps there was only one size initially, but certainly by the time I bought mine there was also a half-sized version called the "Baby Moac". It came threaded with a cable that could have lifted a car! (I still have one somewhere.) Those Moacs were my favourite early chocks, at least until I acquired a set of Chouinard Stoppers!

There was a precursor to the RURP??? A caption to some Great Pacific Ironworks Images reads “Top left is the famous RURP (“Realised Ultimate Reality Piton”), a variant of the original small knifeblade design”. Mr. Middendorf can you tell us anything about the original design? What did that look like? Amazing article, awesome read