Trango 1988 (part b)

Trango History Series--the Kurtyka-Loretan

The view from Urdukas:

Wojciech ‘Voytek’ Kurtyka

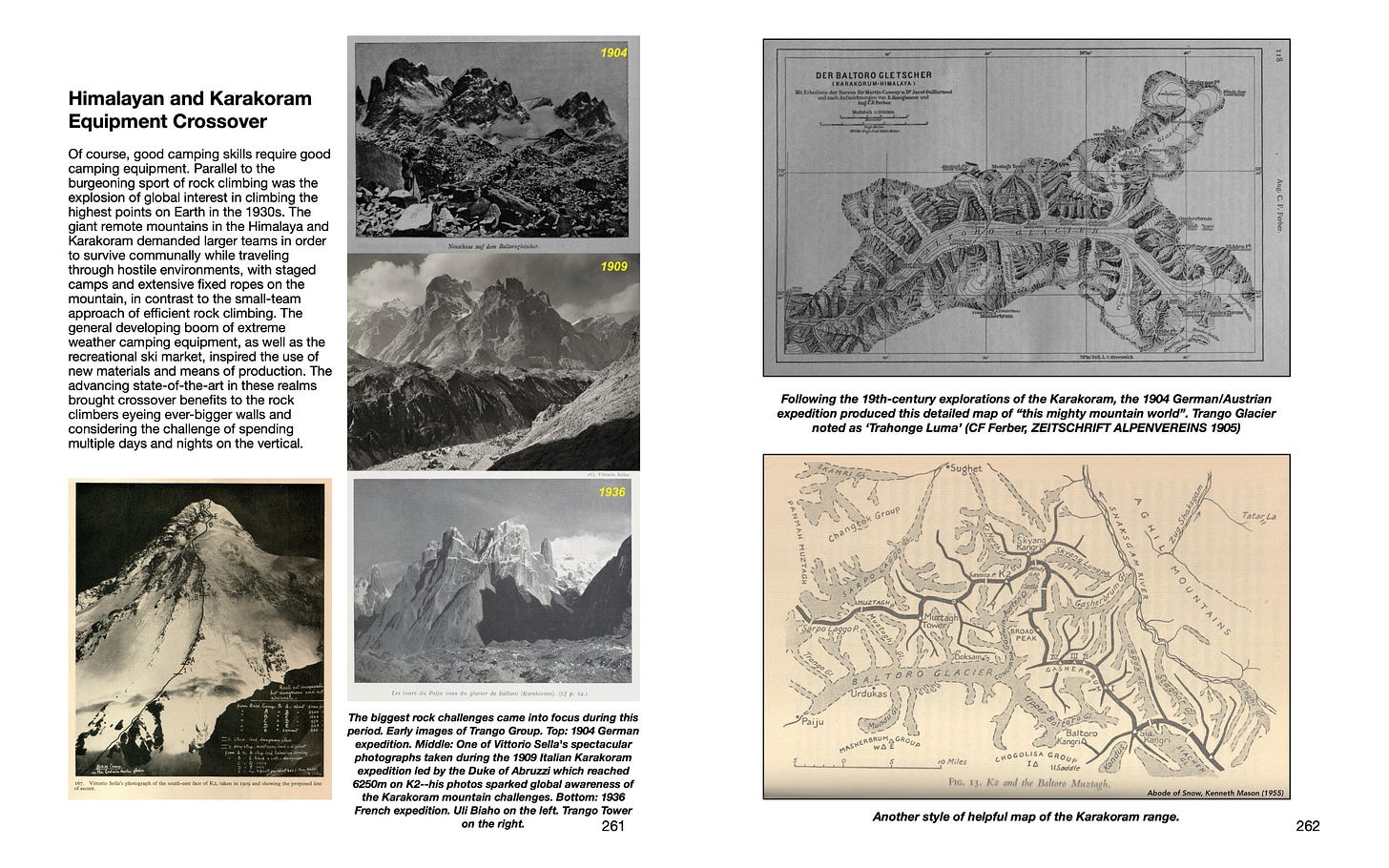

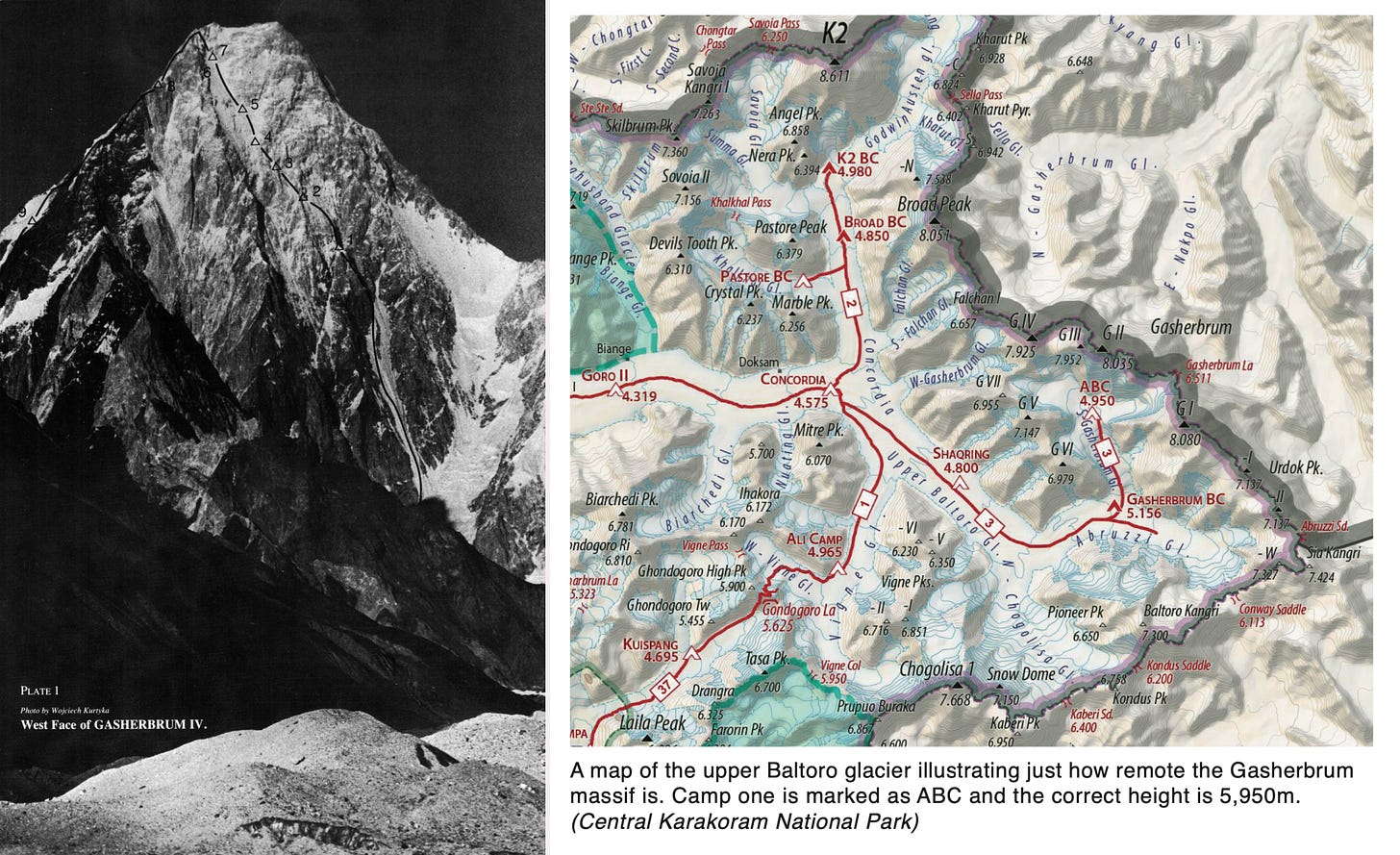

Voytek Kurtyka needs no introduction as one of the greatest of all Himalayan and Karakoram climbers. In 1984, he reflects, “My whole energy has been absorbed by just three mountains: Gasherbrum IV, Trango Tower and K2. Seeking an appropriate partner for those very difficult and risky climbs, I teamed up first with the Austrian, Robert Schauer, and later with two Swiss: Erhard Loretan and Jean Troillet.”

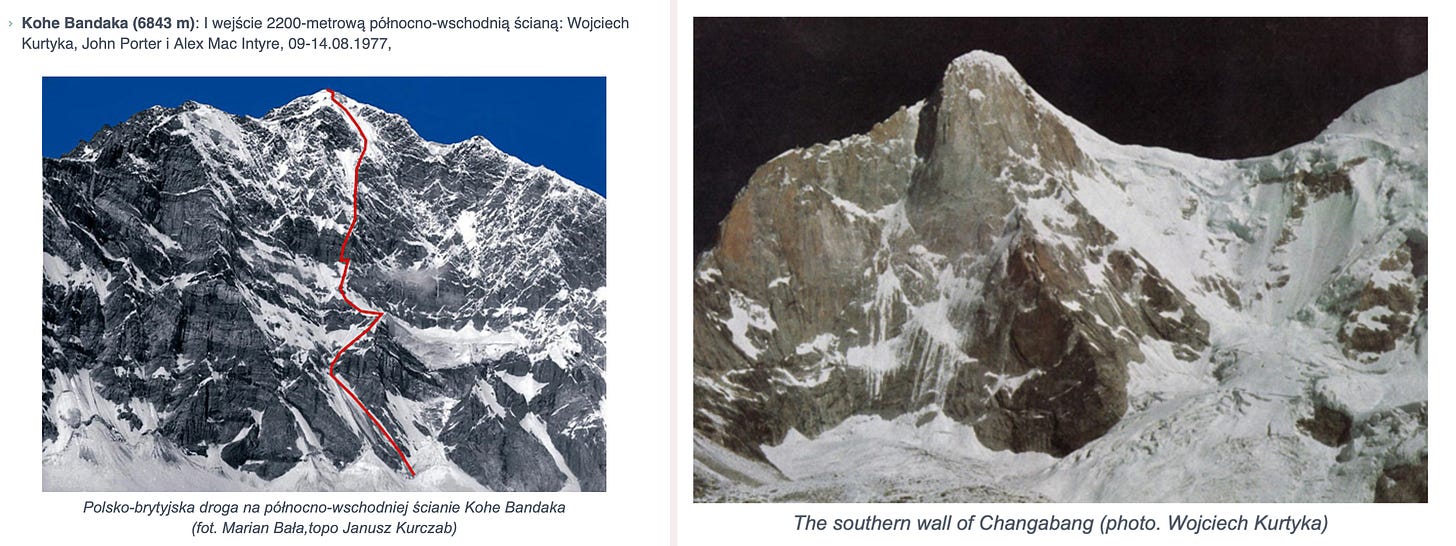

First climbed in 1985, Voytek’s legendary ultra-bold & ultra-light 14-day ascent of the 2500m Shining Wall on Gasherbrum IV with Robert Schauer is still unrepeated despite many attempts of strong climbing teams from all over the world. It is also one of the wildest survival stories of mountaineering.

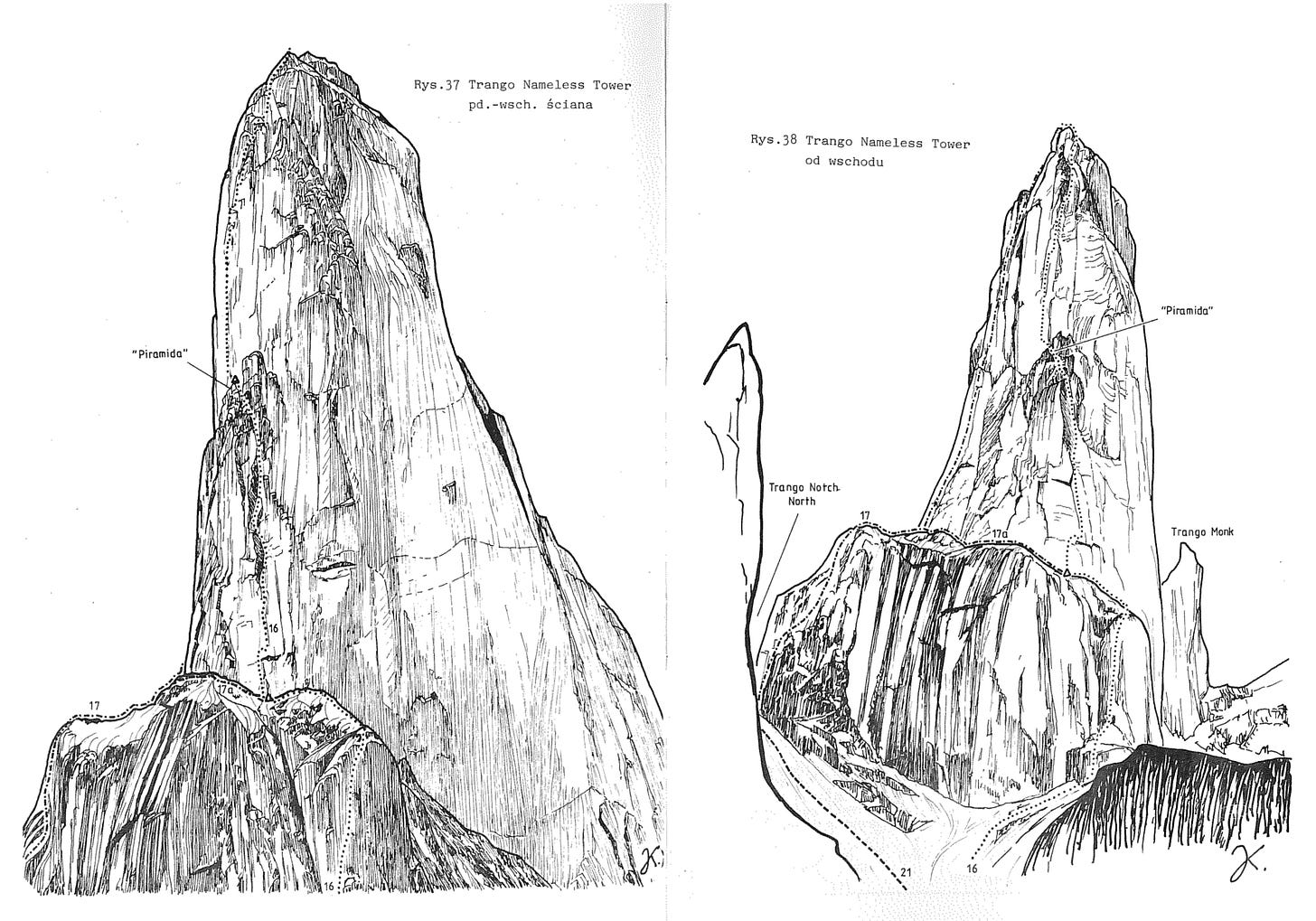

In 1985 Voytek also hatched plans to climb the second ascent of Trango Tower, unclimbed since the original British ascent in 1976, via a new route. Many considered the peak “climbed” and thus problem solved, but as Trango had not yet been ascended from the Dunge glacier, Voytek envisioned the east wall as a separate challenge. At the K2 basecamp in 1985, Voytek met a team of Japanese climbers “who shared the same Samurai ethos” (Voytek email correspondence 2024), and the following year teamed up with Noboru Yamada, Kenji Yoshida, and Yasuhei Saito for the first attempt of the east wall of Trango Tower. (footnote)

Footnote: Much could also be said about longstanding Japan-Poland relations during this time of international political openings. Sadly, Anpei Saito died in Annapurna in 1987, and Novoru Yamada died in 1989 on Denali. Regarding new route attempts on Trango, also of note is the Bolton Expedition of 1984 on a new line to the left of the original Britsh route (climbed by a Spanish team in 1989). Michel Piola was also investigating a new line on the south wall of Trango from the Trango Glacier in 1986. The lull in Trango activity after the original 1976 British ascent also has to do with Pakistan Ministry of Tourism’s permitting of peaks (at times refusing applications from some countries). Greg Child reflects on Trango aspirations, “My trip in 1983 with Doug Scott was mainly to big peaks way up the Baltoro, but the first thing we did was Lobsang Spire. Most of the guys regarded (the lower elevation summits) as a foible - Broad peak, K2 - were the reason to be there. But Lobsang was a perfect little wall (to climb on the way to the big peaks). I was thinking about Trango, it just took me longer to get to it.”

The Japan-Poland Trango Expedition’s arrival at Dunge basecamp was followed by two weeks of efficient teamwork to establish a high camp on the face of Trango Tower, including two impressive days when Voytek fixed ropes on the first 200m to reach the large snow ledge that cuts across the east wall. By June 21, the team had established a well-stocked advanced camp, poised with 150kg of provisions and equipment for the final 800m push on the vertical rock to the summit. The first pitches above the snowledge went slowly, but on their third day, Voytek “tackled a very fine pitch and just as I was scanning the excellent and promising rock above, the astounding call for retreat came from below.” Despite being initially confused about the ensuing retreat (“furious,” he originally noted), Voytek writes upon returning to basecamp, “We slowly came to understand each other. The tension between us vanished. I came back to the plains with two loves greater than before: Trango and the Japanese. Defeats are good.”

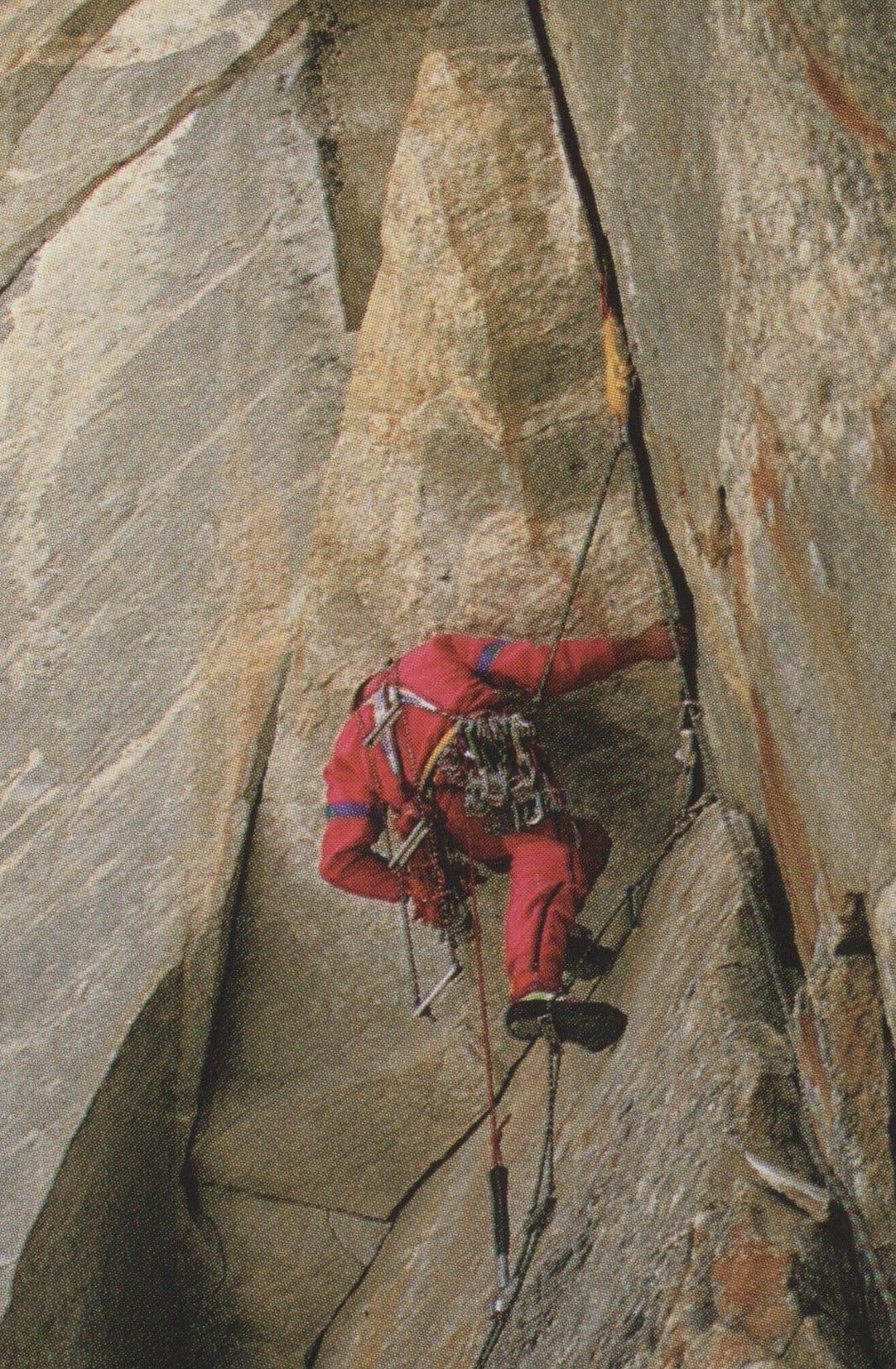

In 1988 Voytek was back for another try at the same line on the right edge of the east wall of Trango Tower, this time with Erhard Loretan from Switzerland, with whom he had previously teamed up on K2. Both were primarily focused on new 8000m routes climbed in ultra-lightweight alpine style but were also vertical rock masters on climbs requiring sizable racks of equipment (footnote). Voytek’s experience, in particular, on hard multi-day vertical walls, involving a bold combination of free, aid, and mixed climbing, was vast. The main bigwall training grounds for climbers from Poland were the Tatras, the European Alps, and the Troll Wall, and in each of these areas, Voytek had climbed the hardest routes.

Footnote: Voytek in particular was more inclined to use more equipment in pursuit of a climb. Bernadette McDonald records specific tensions of different ideas of minimalist equipage on Cho Oyu in 1990: One such explosion erupted over a discussion about pitons. Erhard wanted to take just two up the mountain. Voytek pushed for six. “Okay, you take everything,” Erhard yelled and threw the equipment down. Voytek retorted, “Erhard, you lost a partner on a face for just that reason.” They settled on six. (Freedom Climbers, Bernadette McDonald, 2011).

Tatra Mountains

As new climbing tools developed in the 1970s and 1980s, bigwall aid climbing tactics evolved, and multi-day 900m routes like the Pacific Ocean Wall and the Sea of Dreams on El Capitan were considered the epitome of the sport in terms of tenuous and terrifying aid climbing. Yet the level of climbing difficulty in the Tatras in the 1970s, albeit on shorter walls, required equally tenuous and terrifying gymnastic movement using a combination of free, mixed, and aid with racks of pitons and chocks (footnote).

Footnote: One of the secret weapons exclusive to eastern European climbers was decades of evolution of the “beak” piton, not developed in the ‘West’ until 1988 (see this post). Voytek writes, “In general the tradition of birdbeaks use in Poland is quite monumental. The birdbeaks here were always considered the best pitons in history and in the world. I myself was a passionate user of them and teasing American climbers I couldn't understand how you could survive all your crazy aid climbs without birdbeaks. The only explanation was that you must have been geniuses. Sometimes I suppose the history of aid climbing should be divided into two eras: before and after birdbeaks.“

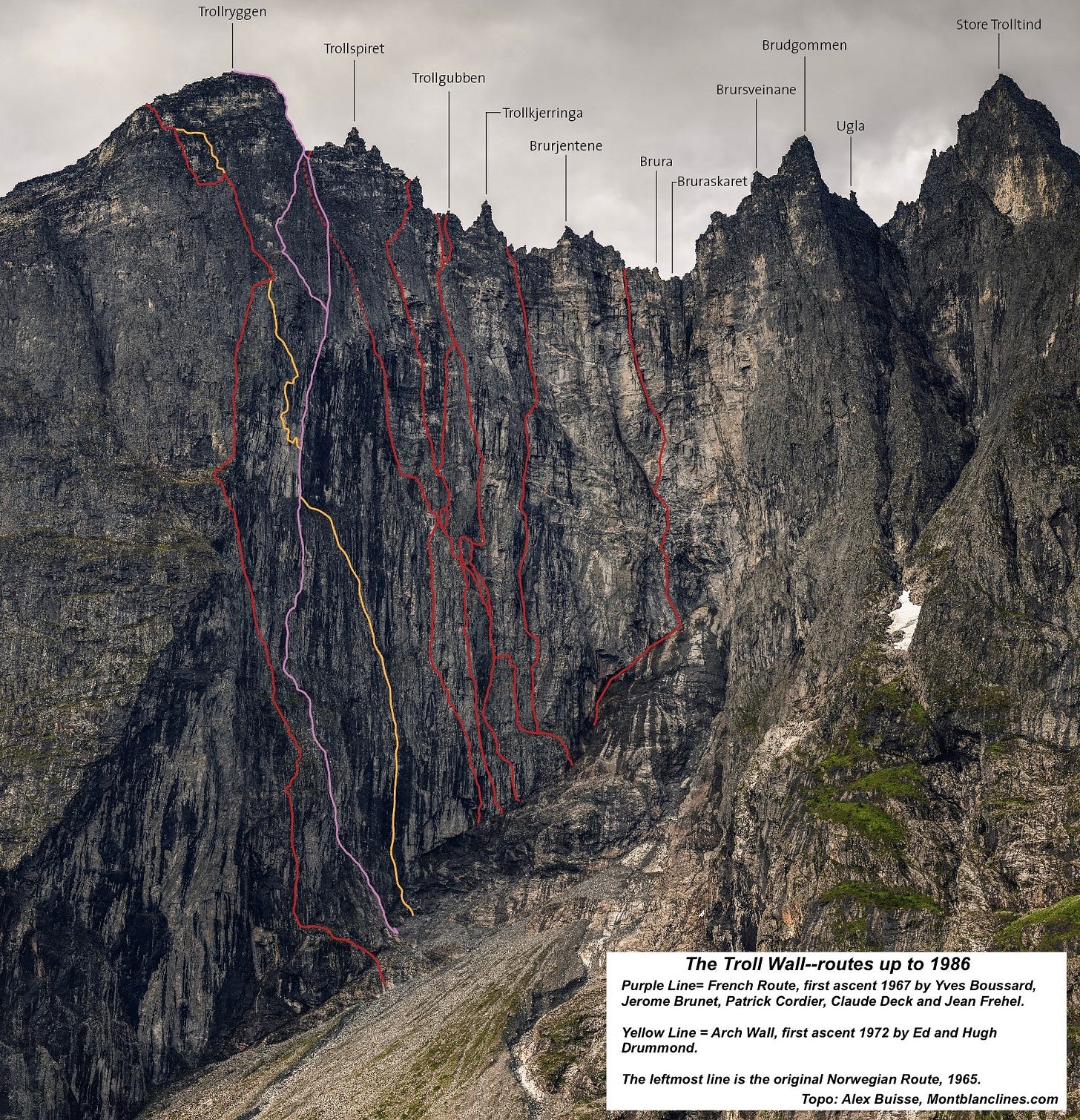

Troll Wall

In terms of training for extreme bigwall routes in the Karakoram, the Troll Wall in Norway is one of the great international bigwall testpieces. Voytek and his team's first winter ascent of the wall via the French Directissima in 1974 was a forerunner of decades of mind-blowing winter ascents worldwide by climbers from Poland which continues to this day. Like many things in the modern world, it is hard to imagine the suffering involved with the relatively primitive equipment of that era, living in slings for thirteen days in winter on the biggest bigwall in Europe, which even in summer can be a miserable wet and cold experience.

Before their ascent of Trango, the pair had also climbed the testpiece bigwalls in the French and Swiss Alps, such as the Robbins-Hemming Direct on Petit Dru, the south wall of the Aiguille du Fou, and other steep rock walls requiring hanging bivouacs on the wall (nowadays climbed in a few hours by the best alpinists), as well as challenging new routes like those on the Eiger and Grandes Jorasses. And of course, both climbers were among the most accomplished on the world’s biggest and most remote mountains. In other words, expert in all disciplines of climbing, and at the top of the game in each one.

By the 1980s, tools and expedition equipment had further evolved, and with the wider availability of camming devices of all sizes increased by an order of magnitude the potential speed of climbing technical vertical terrain, as well as making smaller two-person teams possible. (footnote).

Footnote: Up to this moment in time, bigwall teams on massive remote vertical walls had generally been teams of four people or more, then thought to be more efficient for extended toiling on a bigwall, especially if climbed in a “push” (as opposed to fixing ropes up the whole wall). A four-person team was the standard, so a team of two could always be climbing; the others continuously hauling the heavy kit required for extended weeks and sometimes months living on a vertical wall.

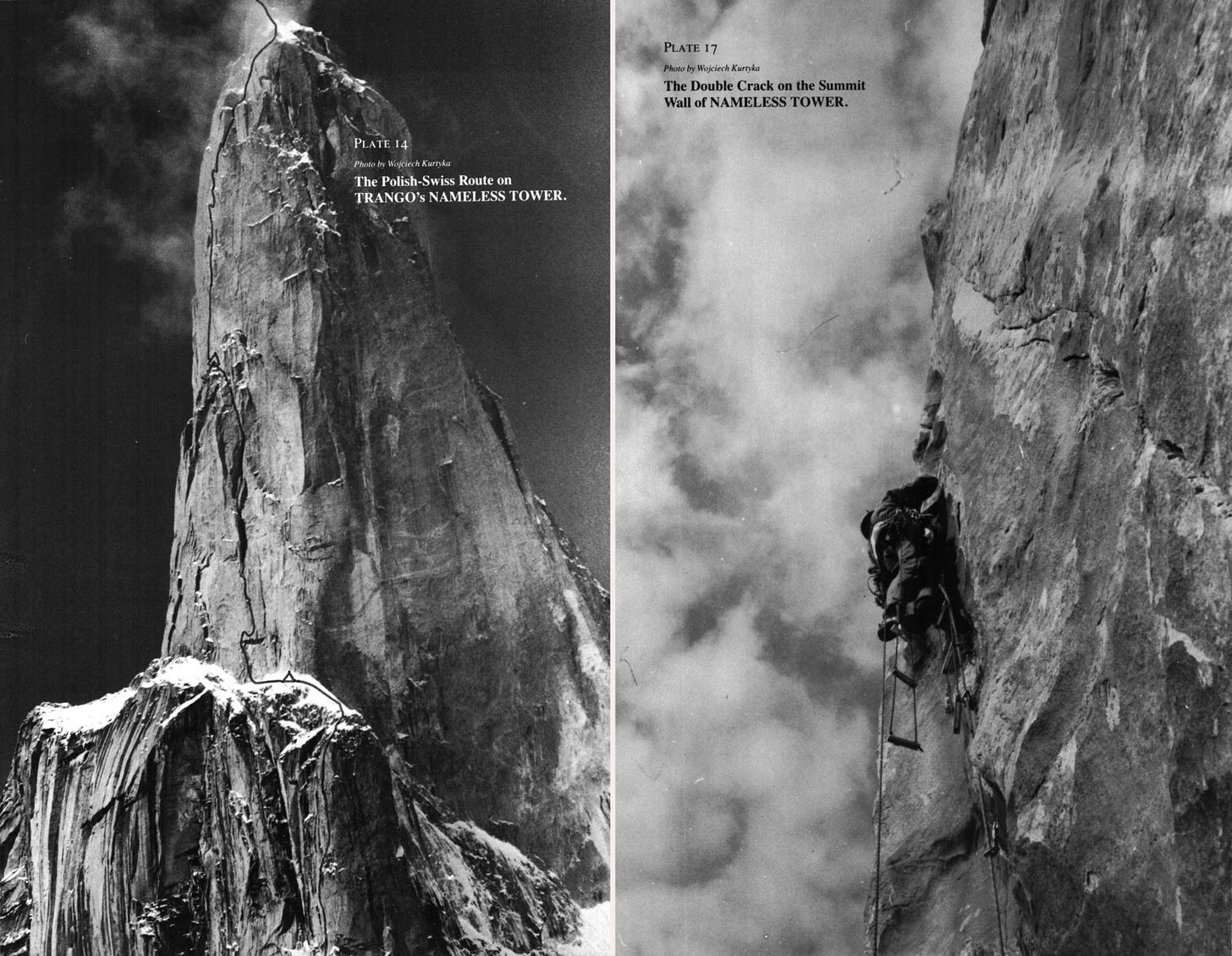

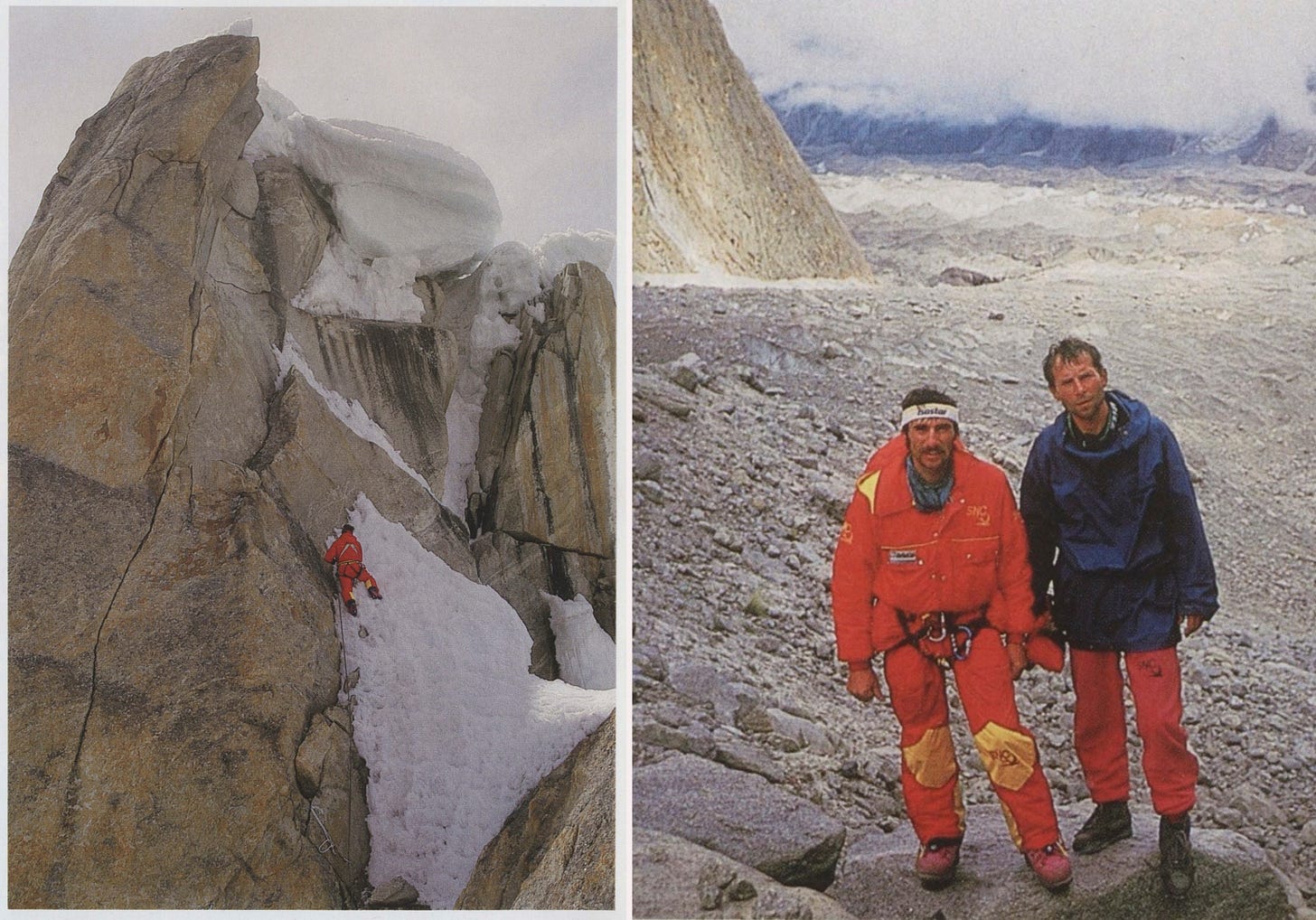

The Kurtyka-Loretan Route, Trango Tower, June 24 to July 14, 1988.

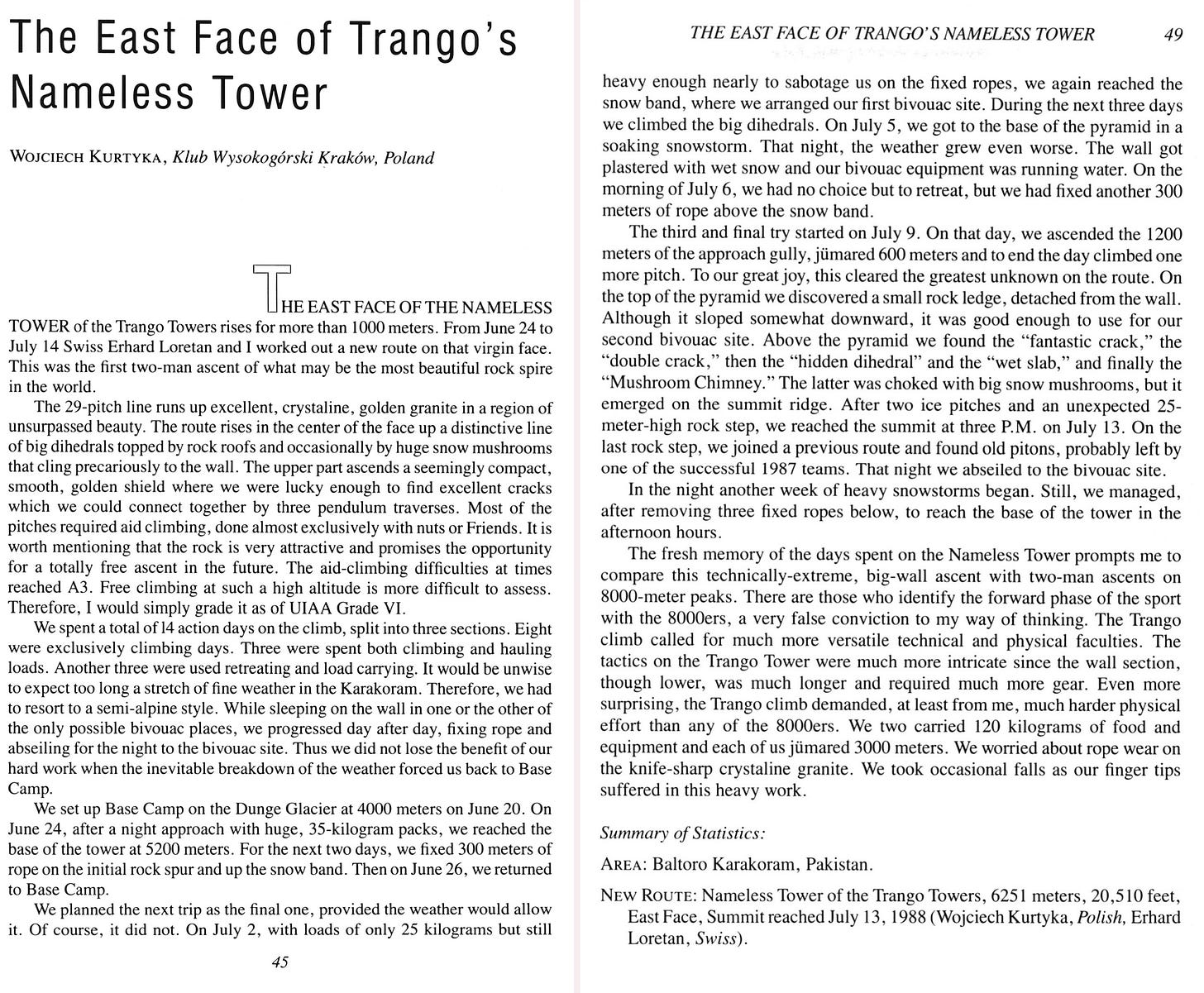

It would be impossible to tell the story of the Kurtyka-Loretan better than Voytek Kurtyka himself, and below is his write-up in the American Alpine Journal (click for larger image). He concludes his trip report:

“The fresh memory of the days spent on the Nameless Tower prompts me to compare this technically-extreme, big-wall ascent with two-man ascents on 8000-meter peaks. There are those who identify the forward phase of the sport with the 8000ers, a very false conviction to my way of thinking. The Trango climb called for much more versatile technical and physical faculties. The tactics on the Trango Tower were much more intricate since the wall section, though lower, was much longer and required much more gear. Even more surprising, the Trango climb demanded, at least from me, much harder physical effort than any of the 8000ers. We two carried 120 kilograms of food and equipment and each of us jumared 3000 meters.”

The route established two camps on the wall, using 600m of rope to climb the wall in three sections (sometimes called “capsule style”), and the success of the two-person team opened new realms of remote and technical bigwall climbing, involving the highest standards of free, aid, and mixed climbing. The route was reported as the “East Face of Trango’s Nameless Tower” but immediately became known as the Kurtyka-Loretan and helped inspire a steady stream of new Karakoram bigwall routes in the following years.

Elsewhere in the Trango Towers area, 1988

The increasing activity in the area led to significant ascents and attempts in 1988, all deserving of their own story (American Alpine Journal reports compiled by H. Adams Carter below):

Trango Towers (Trango Chateau), Yves Astier, Club Alpin Français.

Our expedition was composed of Abdel Amar, Mauro Mabboni, Pierre Montiglio, Olivier Soulié and me. On May 19 and 20, Montiglio, Soulié and I made the first of two routes on the south face of the Trango Château or the First Tower, the main summit of which is 5844 meters high. The weather was bad. On May 27 and 28, Montiglio, Abdel Amar and I made a second route on the face to the right of the first. This time we got to the 5300-meter (17,389-foot) presummit. Again we climbed in a snowstorm. We believe the main summit is still unclimbed.

Uli Biaho Tower, South Face, and Solo on the Great Trango Tower, Maurizio Giordani, Club Alpino Italiano:

Our group consisted of Rosanna Manfrini, Maurizio Venzo, Kurt Walde and me as leader. On June 4, we placed Base Camp at 4300 meters on the side of the Trango Glacier. For two weeks it stormed with abundant snowfall. On June 17, all four of us moved supplies to a small camp at 5800 meters at the base of the immense south wall of the Uli Biaho Tower. On the 18th, we attacked the face and climbed a very difficult 100 meters before descending for the night. On June 19, we returned, spending three days ascending the red granite, which was vertical, very compact and encrusted with ice. We limited aid climbing as much as possible. All four of us reached the summit (6290 meters, 20,637 feet) late on June 21. All night and on the next day, we descended rappelling and got to Base Camp in the evening. Rosanna Manfrini is the first woman to have made such a difficult climb of a 6000-meter peak. The vertical rise is 800 meters and the difficulty from 5.10 to 5.11 and A3. On June 25, I left Base Camp alone, crossed the Trango Glacier and approached the Great Trango Tower. Without any protection gear, I attacked the north face by a route I had studied from the Uli Biaho Tower. In a little less than nine hours, I climbed the 2000 meters to the summit (6280 meters, 20,604 feet). This was the first solo ascent and the fourth following Norwegian, English and American ascents.

Great Trango Tower Attempt, Eric B. Sandbo, Alpine Club of Canada.

On May 27, Doug Dean and I left Base Camp directly across the Baltoro Glacier from the Trango group and hiked to the base of the gully below the west side of the Nameless Tower, hoping to repeat the Selters-Woolums north-face route on the Great Trango Tower. The next morning we ascended to camp in the shelter of a rock close below the base of the Nameless Tower. On the 29th, we followed a snow ramp out to the right side of the gully. We camped and rested a day at about 17,500 feet. On the 31st, Dean waited out a series of snow squalls and left alone at dawn for the summit. He climbed steep, rotten snow onto the upper glacier, saw another storm coming and cached his pack. By the time he had ascended the headwall and cut through the cornice, he was in the thick of the storm. He was on a double-corniced ridge about 200 feet west of the summit. He traversed to a point 25 feet directly below the summit. Rather than risk the corniced summit alone, he returned to camp, where we weathered the storm until the following dawn. We descended to the junction of the Trango and Baltoro Glaciers in a few hours, but poor visibility kept us from crossing that day. We rejoined our friends at Payu on the evening of June 2. Other members were Michael Woodworth, Ed Gunkel, Bill Noble and Tim Rashko.

Nameless Tower of Trango Attempt, Masaharu Gando, Japan.

Hisao Onami, Izuru Okada, Yasushi Sato, Masahiro Ishiguro and I reached Base Camp at 4150 meters on the Dunge Glacier on July 15. After ferrying loads to the base of the wall, on July 27 we began to attempt what probably was the Yugoslav route climbed in 1987. We found fixed rope, but it was almost useless. On July 28 to 30 we climbed seven pitches and fixed ropes to the lower pedestal. On the 31st we set up Advance Base at 5600 meters on the pedestal. Bad weather stopped us for three days. From August 5 to 8 we climbed 14 pitches. On the 8th Okada, Ishiguro and I bivouacked at 6050 meters, 200 meters below the summit, but on the morning of August 9, the weather was bad and so we had to retreat to Base Camp.