What's in a name?--Trango

Trango History Series by John Middendorf

On elevation and names-Baltoro

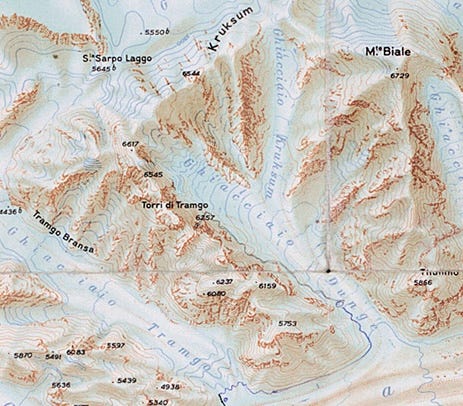

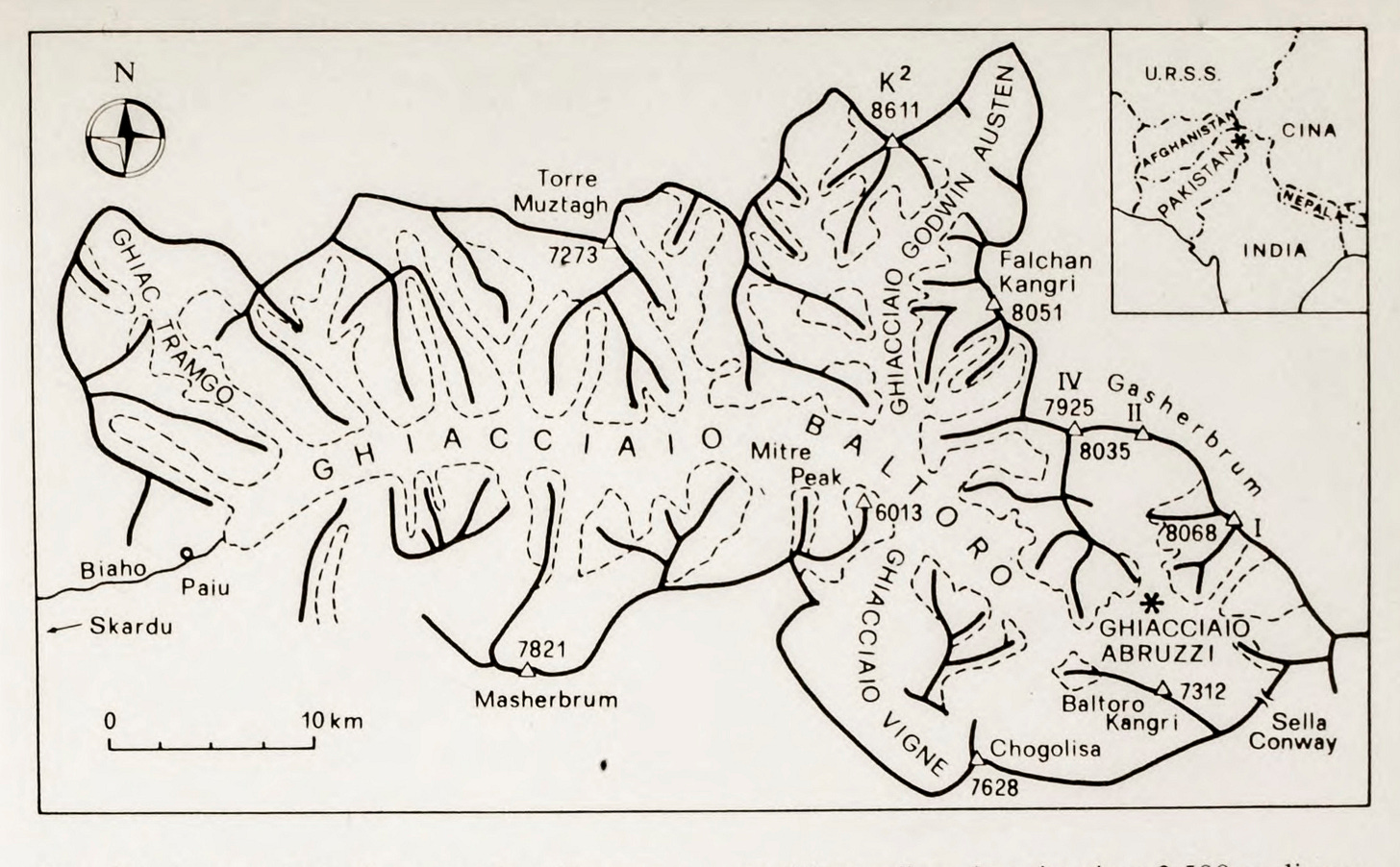

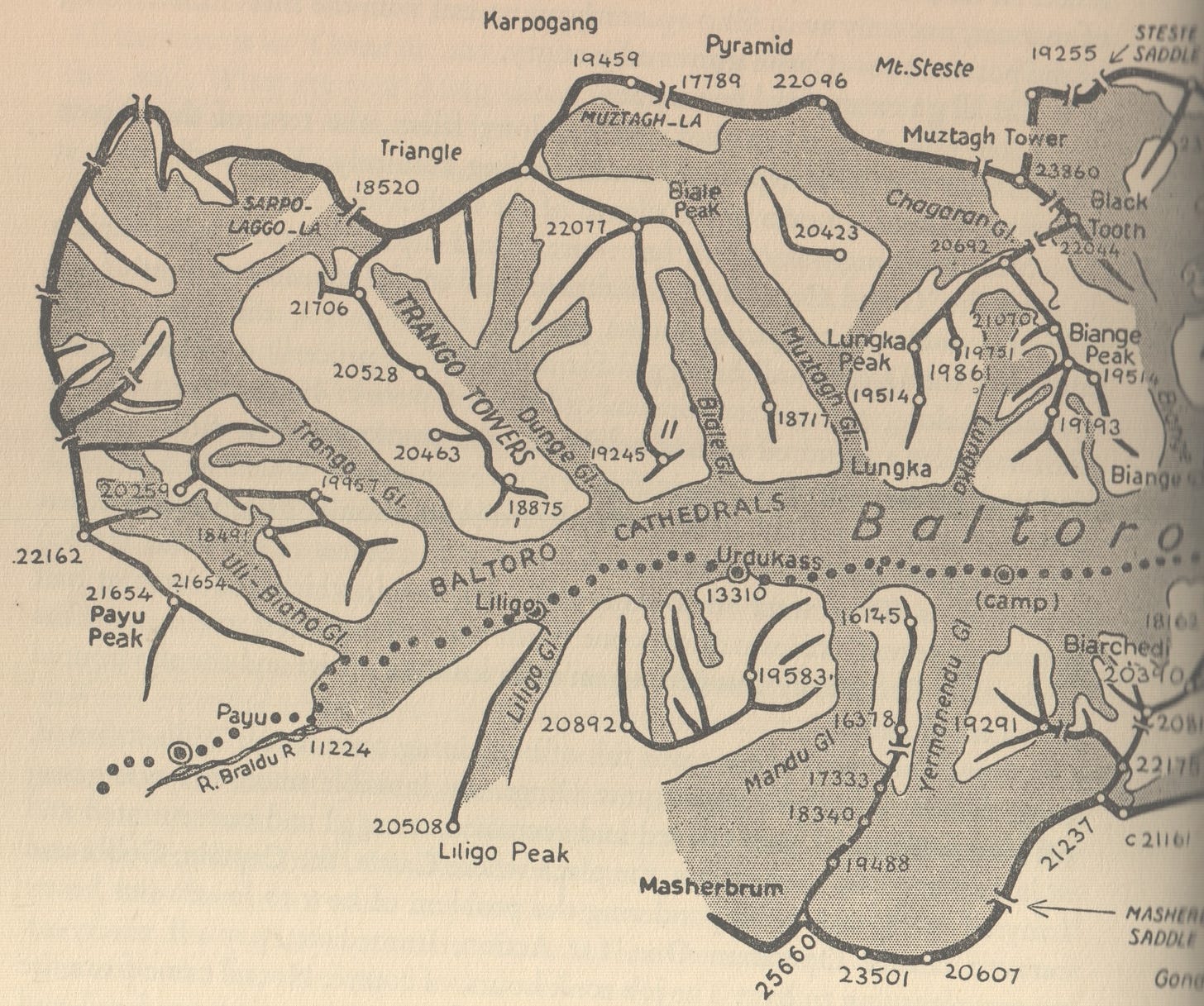

Measurements: The measured heights of the Karakoram mountains evolve as time goes on. On modern Karakoram maps, the elevations are often inherited from earlier less precise surveys; there is still uncertainty about the relative heights of many of the glacial carved Trango Tower summits, which are all several hundred meters below their immediate more mountainous neighbors: Masherbrum (7821m), Paiju (6501m), Biale (6841m), and Trango I, Trango II, and Trango Ri higher up on the Trango ridge (footnote).

Footnote: Though lower than the surrounding mountains, the multiple summits of Great Trango and Trango Tower are all very close in elevation, all part of the same block of a young and uniform 2500m granite batholith, glacially carved and continuously eroding (see this post). Regarding surveys, it is easier to triangulate the higher mountains than the lower rocky summits which have limited visibility from various vantage points. Masherbrum (then K1) was the mountain most of interest to the early lower Baltoro surveyors.

Names: Names of the peaks and glaciers also change and evolve—before the European expeditions began measuring and mapping the peaks and valleys of the Karakoram in the 19th century, many landmarks had indigenous namings based on legend and story. What began as a name for a campsite was applied by early mapmakers to a nearby glacier, and then applied to peaks and even entire regions. The Baltoro Glacier’s name seems to derive from the name of a Balti campsite far downstream past Askole, and the original meaning of ‘Baltoro’ appears lost to time. (footnote).

Footnote: Ad Carter in the 1975 American Alpine Journal writes: “There was little agreement on the name Baltoro. The explanation given by Burrard and Hayden* from Tibetan dPal-gTor-po (spreader of abundance) seems unlikely. Other explanations were based on bal (wool), balto (clay used to mix with wool to extract lanolin and dirt) and Balti (the people of the region).” *A sketch of the Geography and Geology of the Himalaya Mountains and Tibet by S.G. Burrard and H.H. Hayden. Delhi: Geodetic Branch, Survey of India, 1933. Fosco Maraini speculates that Balti derives from the Burushaski root, ‘Those of the rocks, of the steep-sided mountains’—other writers since have proposed other evidence and uncertain speculation. Regarding elevations, the 1990 Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research published elevations in the Karakoram seem to be the most accepted, with Trango Tower measured at 6239 meters.

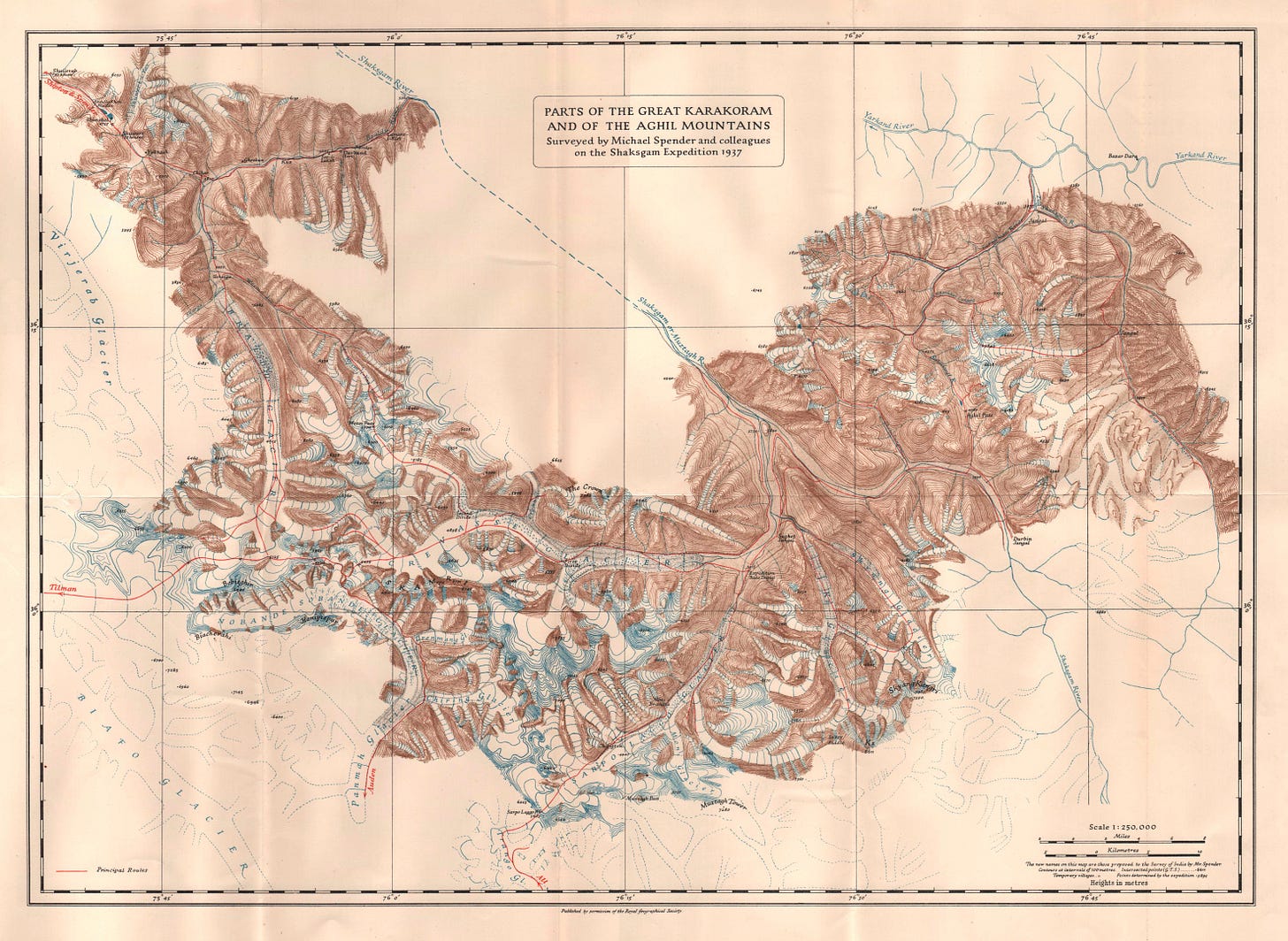

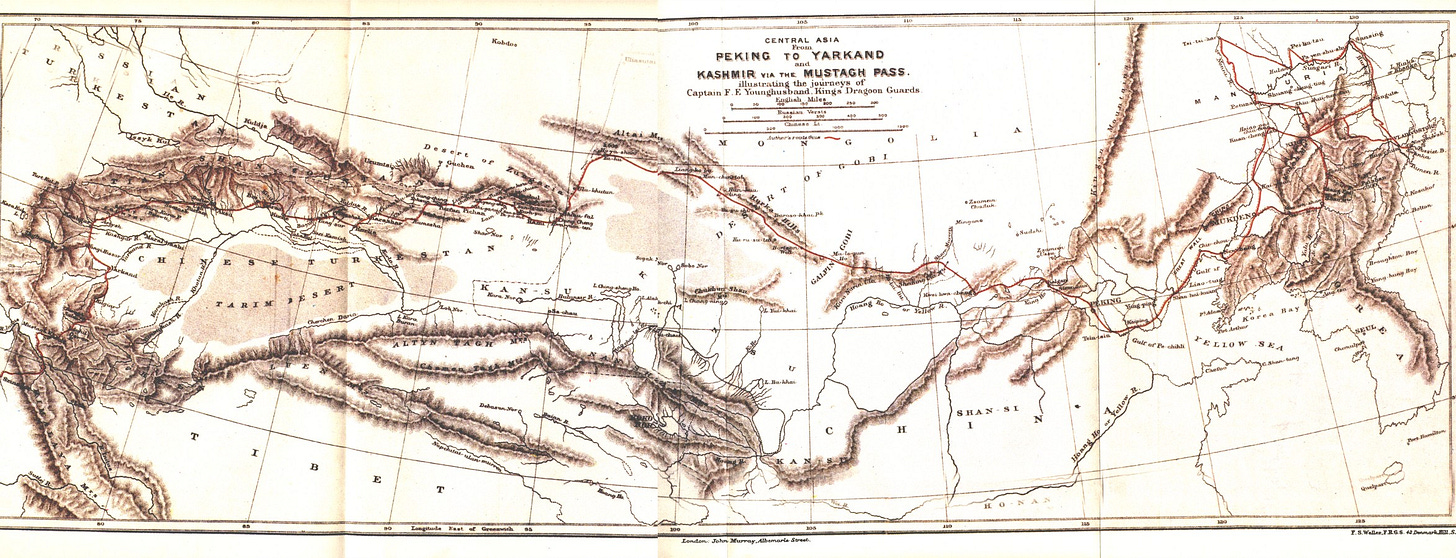

The protocol for the early mapmakers was to use local names when naming features, and perhaps slip in a few eponymous names, such as the Younghusband Glacier named for captain Francis Younghusband (1863-1942), who traversed the length of the Himalayan-Karakoram chain with his Kings Dragoon Guards in 1887. Until the 1930s, names in the Karakoram were pretty fluid, depending on the mapmaker and language, but by 1937, a Karakoram committee within the Royal Geographical Society was established to confirm named features. (footnote).

Footnote: As India (and Pakistan) were still a British colony until 1947, The Royal Geographic Society worked closely with the Survey of India to create official names; some places got special treatment: “The practice of the Survey of India in the past has been that no names should be entered on its maps, of areas for which it considers itself responsible, unless they have been found to be of local or at least indigenous origin. It has admittedly departed from this practice in the case of Mount Everest, but it will be generally agreed that the highest mountain in the world is entitled to special treatment, especially when the result was so euphonious. In the absence of a local or indigenous name, the old practice was to allot a symbol, usually a letter and a number. This practice has however been abandoned on our maps for many years except in the case of K2 which, as probably the second highest mountain, is perhaps also entitled to special treatment. (Kenneth Mason, Karakoram Nomenclature, The Geographic Journal, Feb. 1938). Also of course is the Godwin-Austen Glacier, named for Henry Haversham Godwin-Austen (1834-1923), the first European explorer to the area (1861).

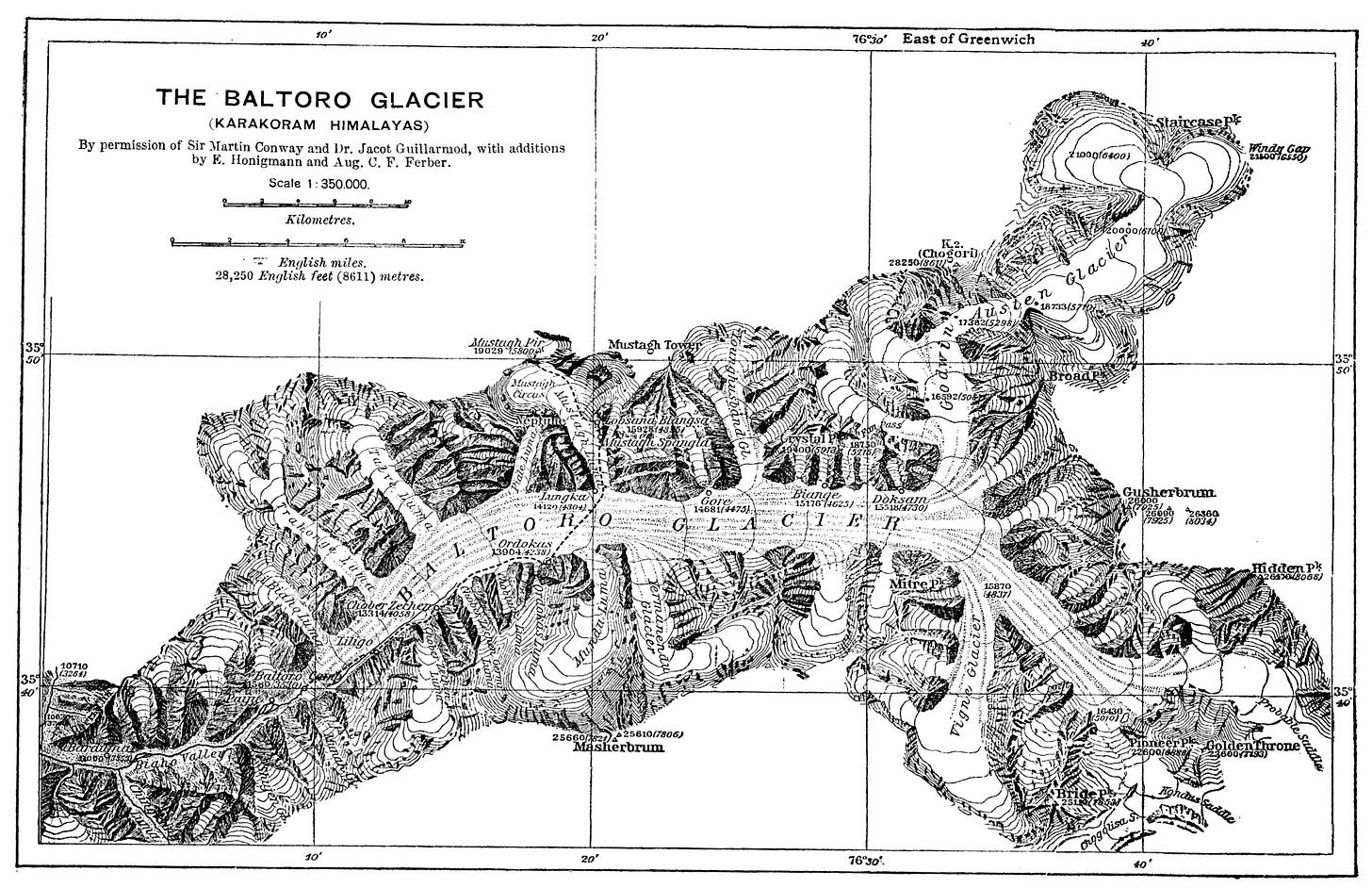

First detailed map of the Baltoro

The alpinist and mapmaker Martin Conway (1856-1937) created the first detailed map of the Baltoro Glacier, using simple and portable surveying instruments (a 3-inch transit theodolite and a small plane-table), and the latest photogrammetry survey techniques. He describes his six-month journey in 1892, climbing and surveying: “Every detail of rock faces, ridges, ice-falls, and the like that time permitted to be sketched in on the spot was recorded. Over a thousand photographs were taken for the purpose of further elaboration of detail in the redrawing at home. As works of art the photographs were not very good; but they were invaluable for topographical purposes. On my return to England I spent nearly four months in drawing out the whole map afresh, on the scale of one inch to a mile, and colouring it as in the published copy.”

1894: Trango’s first name: Uli Biaho

A close-up of Conway’s map reveals his naming of the first major tributary of the Baltoro as the Uli Biaho Glacier. The most prominent feature rising above this glacier is now named Uli Biaho Tower, but the name was later moved south to identify a smaller dead-end glacier to the southwest. As a major tributary of the Baltoro, this valley was a potential passageway to Xinjiang to the north. Conway’s mapping of the glacier's far reaches and upper branches was of strategic interest. One of the aims of the European explorers and mapmakers was to find routes from Askole to the Shaksgam Valley, a strategic border region in southern China (formerly part of Kashmir and still in dispute—in 1937 Eric Shipton famously found a route to the Shaksgam Valley via the Trango Glacier as recorded in his book, Blank on the Map). The only pass known at the time to the Royal Geographic Society that crossed the Karakoram from the Baltoro was the Mustagh Pass, made famous by Younghusband’s crossing from the north, but with its exact location still unclear.

1907: Trahonge Luma

During his search and mapping of Mustagh pass in 1903, August Ferber surveyed the lower Baltoro and in 1907, submitted a new map to The Geographic Journal, labeling Conway’s Uli Biaho glacier as the Trahonge Luma (Trahonge Valley). Although Ferber researched and provided some local sources for naming, for example, “Mustagh (= ice mountain) Pir (= pass), in the heart of the Karakoram (= black gravel)”, there is no hint of the origin of Trahonge, the linguistic root of what was to become Trango. Curiously, the first version of this map (based on photographs with no elevation data) named the glacier ‘Tramgo’, and the Trahonge and Tramgo names co-existed for a few decades. (footnote).

Footnote: The original map was created by Charles Jacot-Guillarmod (1868 - 1925), a Swiss topographical engineer, well known for stunning high alpine cartography of the Swiss Alps using photogrammetry (which does not require a survey, only photographs). Charles Jacot-Guillarmod also created the “Mount Everest and the group of Chomo Lungma” map in 1925. The photographs were collected by Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles’ cousin and mountaineer, during his trekking along the Baltoro Glacier to K2 during the 1902 Eckenstein-Wessely-Guillarmod expedition (often now known as the notorious ‘Crowley K2 expedition’). August Ferber used this map for his 1907 Royal Geographic survey results. In the chronicle of the 1909 Abruzzi expedition, De Filippi notes the discrepancy: “Conway gathered names from the natives for most of these tributary glaciers. Guillarmod made further inquiry, and changed the names about from one glacier to another, adding new ones. Ferber kept these names for the glaciers, but added others for the valleys down which they run. The Workmans, too, rearranged or changed the names given by Conway to the confluents of the Hispar glacier. Probably every voyager to these regions at intervals of a few years could collect data for further changes. It is evidently not alone in the inhabited portions of Baltistan that the names of valleys and rivers change. It is to the interest of the geographer to establish a fixed nomenclature—he cannot be expected to conform with capricious changes. The Duke has adopted in his map the nomenclature of Guillarmod, as being simpler than that of Ferber.” (Karakorm and Western Himalaya 1909, Filippo de Filippi, 1912).

1929: Tramgo to Trango

The Italians were also interested in filling the blanks on the Baltoro maps in the early 20th century. The Duke of Abruzzi, whose primary interest was to climb K2 in 1909, referred to the lower Baltoro peaks as “stony wastes” and referenced the side glaciers as various northern ‘confluents’ without much fuss about the names (though the expedition did produce a detailed map of the Upper Baltoro). In the account of the expedition, Tramgo Glacier is only referenced in a panorama photograph:

In 1929, the Duke of Spoleto followed in Abruzzi’s footsteps and produced a further Baltoro map, this one focused on the complete passage from Askole over Muztagh Pass to the Shaksgam Valley to the east. Although the trip’s geologist and geographer, Ardito Desio, referred to the Trango Glacier as Tramgo with a ‘m’, the Royal Geographic Society published the name as Trango in a preliminary map. Perhaps it was a typo, not acknowledged until 1938 when the name was officially changed to Trango within the Royal Geographic Society.

Footnote: Kenneth Mason, Co-founder of The Himalayan Club in 1928 and the keeper of Karakoram names within the Royal Geographic Society, and who later wrote Abode of Snow: A History of Himalayan Exploration and Mountaineering in 1955, notes of the map in 1938: The heights of various conspicuous summits are given on Spoleto's map (of 1929) between the Trango and Dunge glaciers, but we do not know the height of the most conspicuous summit, the Trango Tower. The spelling Trango is probably better than Spoleto's Tramgo, or the older Survey spelling Trahonge.” —Kenneth Mason, Karakoram Nomenclature, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 91, No. 2 (Feb. 1938). What ‘Trango’ originally meant is still a mystery; Ad Carter records it as deriving from Tramga, the name of an ancient shepherd’s hut near the confluence of the Trango and Baltoro glaciers, which makes sense as the way Guillarmod described it. whereas the Balti cook on one of Greg Child’s expeditions, Rasool, said Trango likely came from the local word Tengos, for a bottle of hair oil, presumably resembling the slender Trango Tower. No one knows, the origin is lost to time. Regarding Tramga/Trango, Fran Middendorf (my sister, fluent in Italian) writes this: “Up in the Dolomites there is a particular dialect (Ladin)and Tramga might have come out of that dialect. Trango has a masculine ending and sounds more appealing to the English ear. All the letters have the same pronunciation basically in both English and Italian -the a is a bit longer- aaa the r has a roll but the n,m, and g are hard sounds like in English.”

Tramgo persists: Regardless of the Royal Geographic Society’s spelling, Italian maps and journals continued to use “Tramgo” even into the 1980s:

1938: Trango Group still nameless:

While the two names for the first major tributary of the Baltoro coexisted, the rocky towers between the Trango Glacier and Dunge Glacier were still grouped and identified as part of the Paiju Group of peaks, and sometimes part of the Lobsang Group. The border tug of war was settled in February 1938, when Kenneth Mason was the first to differentiate the Trango Group in his article Karakoram Nomenclature in The Geographic Journal, setting the name ‘Trango’ in stone, so to speak: “Trango group, east of the Paiju group, includes the mountains east of the main trunk of the Trango glacier and those west of the Dunge glacier (longitude 76º 13'). And now, with their own name, the individual summits began to be surveyed and labeled.

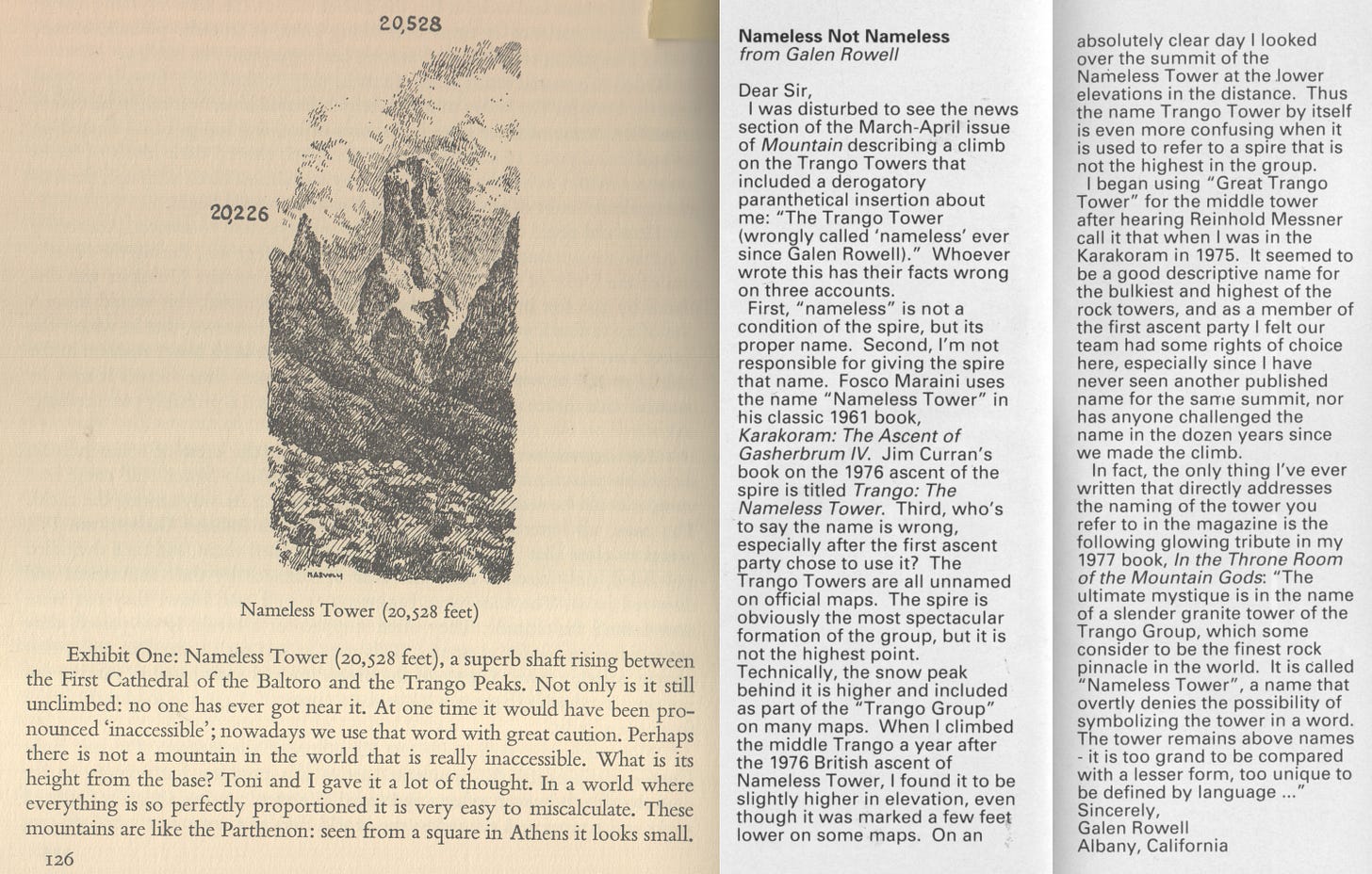

The story of Nameless Tower (1961-1975)

Speaking of names, or lack of them, the well-known story of Nameless Tower can be briefly recounted here. ‘Nameless Tower’ appears as ‘Exhibit One’ of the ‘world’s most spectacular museum of Shape and Form’ in the 1961 book, Karakoram: the Ascent of Gasherbrum IV, by Fosco Maraini. Maraini describes the Towers of Trango that appear in many Karakoram photographs and highlights the “superb shaft rising between the First Cathedral of the Baltoro and the Trango Peaks” (between the Château and Trango Ri). Dubbing the inaccessible peak ‘Nameless’ intrigued the broader climbing community as well as those who had passed through Urdukas on their way to the bigger mountains in the 1950s and imagined its first ascent. Pakistan border conflicts closed the area to climbing from 1961-1974, and when the region finally re-opened to mountaineering, the competition for the sole permit allocated to the Trango group, to climb the fabled ‘Nameless Tower’, was international.* After the first attempt in 1975, the Alpine Journal identified the spire as ‘Trango Tower’, and though many still think of it as ‘Nameless Tower’, Trango Tower has become the more common name.

*In 1975, nineteen mountaineering expeditions from America, Poland, France, Italy, Britain, Switzerland, Austria, and Japan were allocated permits for various objectives. The first permit for the Trango group was secured by Chris Bonnigton, the “maestro of international diplomacy.” —Jim Curran, Trango-The Nameless Tower, 1978 (story of the first attempt in 1975, and the first ascent in 1976). Regarding the 1961-1974 closure, a six-person French team were the first to obtain a Karakoram mountaineering permit for Uli Biaho Tower (then unnamed) in 1974 (unsuccessful).

Further Naming

The earliest summit surveys identified four distinct high points in the Trango Group, which today correspond to Trango Château, Great Trango, Trango Tower, and the Trango Ri’s, the snowy high peaks on the ridge past Trango Tower to the northwest. Further names will be detailed as this research progresses.

Naming Tidbit: The prominent spire at the end of Trango Glacier, now called Shipton Spire, was originally named L‘Ainablak, and that name was shifted to coin the more concealed spires to the south of it. From the 1999 AAJ: [Directed by Greg Child, Bernard Domenech (France) contacted the AAJ in the autumn of 1998 with a note on the naming of Shipton Spire. He wrote, “[In the 1936 expedition report], Ardito Desio gave the mountain [the name of Hainablak] because his porters, [who were from] the Baltic region, named it this way. [They]... remember that the remarkable wall opposite Brangsa, the last bivouac before the traverse [into China], always used to be called Hainablak....”] A letter to the AAJ 1999 from Ghulam Parvi clarifies “The shape of Shipton Spire looks like a hard and smooth surface. When there is rain or the nearby water and snow give light, the reflection of the peak looks like a mirror. The local Braldu valley people call Shipton Spire “(H)aina Brakk” (pronouced ‘aa- ee-na blakk’).” A neighboring tower, Cat’s Ears, is another recent name.

Next: Climbs on The First Baltoro Cathedral, known by many names (First ascent of Le Château, 1987).

Appendix: