Zion Climbing in the 1930s

Mechanical Advantage: Tools for the Wild Vertical draft for Volume 2

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

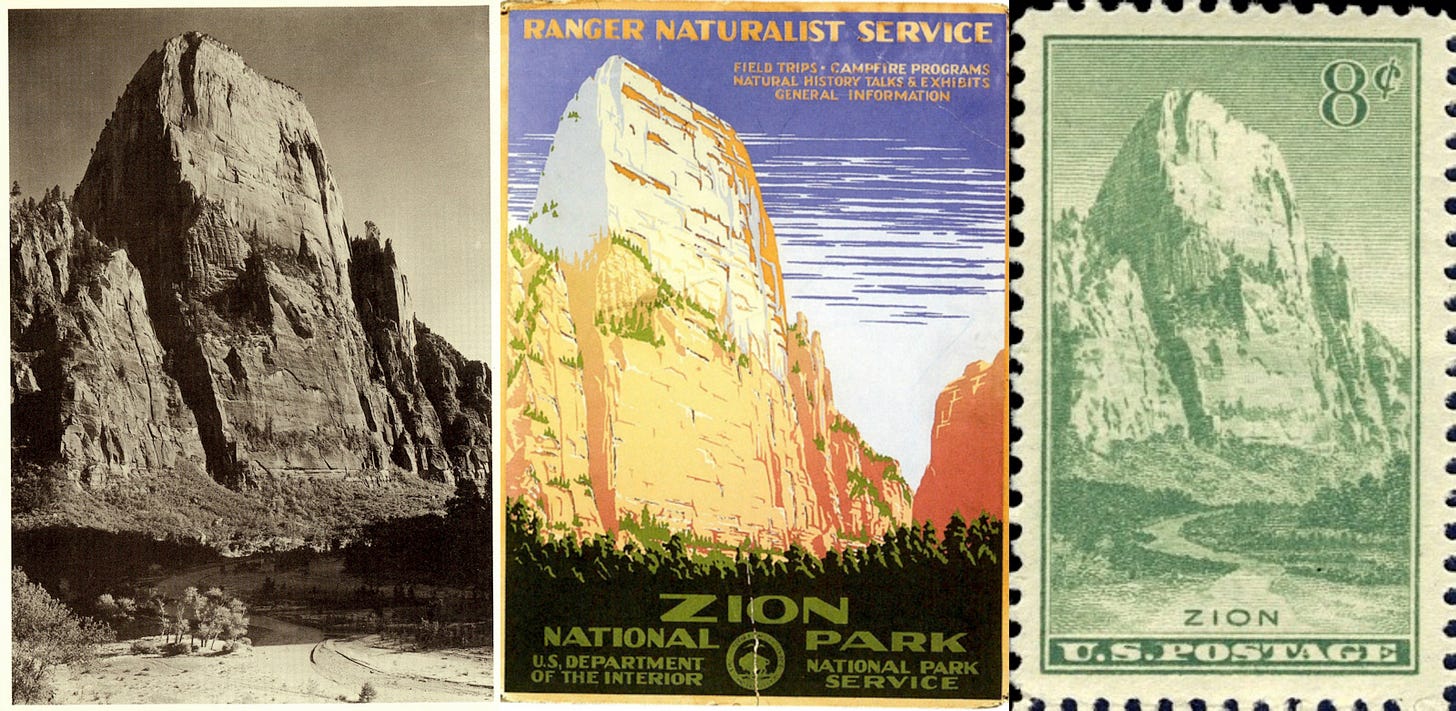

Daredevils in Zion—the Great White Throne

In June, 1927, Bill Evans, a "distinctly daredevil type and a mountaineer" (superintendent's memo 7/13/27) set out to climb the Great White Throne in Zion National Park, armed with only 15 feet of rope and a small canteen of water. Evans was inspired by a Los Angeles Times article calling the Great White Throne “the vast keynote of Zion” and that “the foot of man has not scaled it.” After being thwarted by steepening walls on the north side, Evans found a route to the southern saddle, then made his way up slabs to the summit where he spent the night, lighting several signal fires visible to folks in the Grotto auto camp far below. The next day he did not return, and a historic rescue effort was organised by chief ranger Walter Ruesch (for whom Walter’s Wiggles on the Angel’s Landing trail is named). After days of searching on the steep terrain, Evans was found tangled up in a manzanita bush near the saddle, delirious and weak, having been without water and food for nearly three days in the Zion summer heat, and remembering little of the preceding days. He was carried down by a makeshift stretcher constructed on the spot from wood poles, rope, and Ruesch’s overalls, and required months to recover. He later recalled intentionally initiating a controlled slide down the steep slabs, but lost control and tumbled hundreds of feet.

Evan’s ascent of the Great White Throne became famous and was reported in over 100 national newspapers, but it was the skill and daring of the rescuers that was celebrated locally. The park superintendent’s report concludes, “The point that always strikes me is the selfishness of some of the people who try these things. They race off in a reckless manner, trying to secure some empty glory for themselves by doing something a sane person would never attempt when they get into trouble, and it is necessary to risk the lives and limbs of others trying to help them out.”

Second daredevil ascent

The second reported climb of the Great White Throne was another soloist in 1931, by Don Orcutt who reported finding a human scull on the summit, “yellow and brittle with age”, perhaps from a previous era and further evidence of the climbing abilities of Indigenous peoples. A few days after his Great White Throne ascent, Orcutt fell while trying to climb Cathedral Mountain, and his demise from “a 1000-foot fall” was widely reported in national newspapers, while the 1932 American Alpine Journal noted, without naming Orcutt, “The crumbly sandstone monoliths of Zion National Park have also claimed a victim, a solitary climber, whose fall may probably be explained by the deciduous nature of the handholds.” These solo ascents were condemned by the park, as they were "improperly executed and done in a manner that is strongly disapproved by all alpinists having recognized reputations" (1931 Park Service memo).

Footnote: In September 1937, Fritz Weissner is recorded to have attempted the Great White Throne with W. Allemann, but failed for unknown reasons; in November 1937, Glen Dawson and team completed the third recorded ascent of the Great White Throne prior to their East Temple climb. In 1949, on the fourth reported ascent, Herb and Jan Conn described the route to Richard Leonard as “pure friction work up a surface well lubricated with sand grains. The hands are almost worthless. The main problem is to judge where the angle is lowest and to find dependable anchors, usually scrubby bushes, within a rope's length of each other. We used three bolts to supplement the bushes. (It doesn't take much more than two minutes to drill a two-inch hole!)”. In 1976, Paul Horton reports “It was more difficult than we expected -- although we would only rate it about F6. There are long unprotected runouts on difficult friction and some poor belay anchors. We saw many old bolt holes and found one fixed piton.”

Alpinists discover Zion

In the summer of 1931, German alpinists Walter and Fritz Becker, along with the American Rudolph Weidner, successfully climbed Cathedral Mountain with rope and belay, involving a difficult chimney and an overhang that "taxed all their powers of ingenuity and endurance to pass." It is not known if they had pitons or other gear.

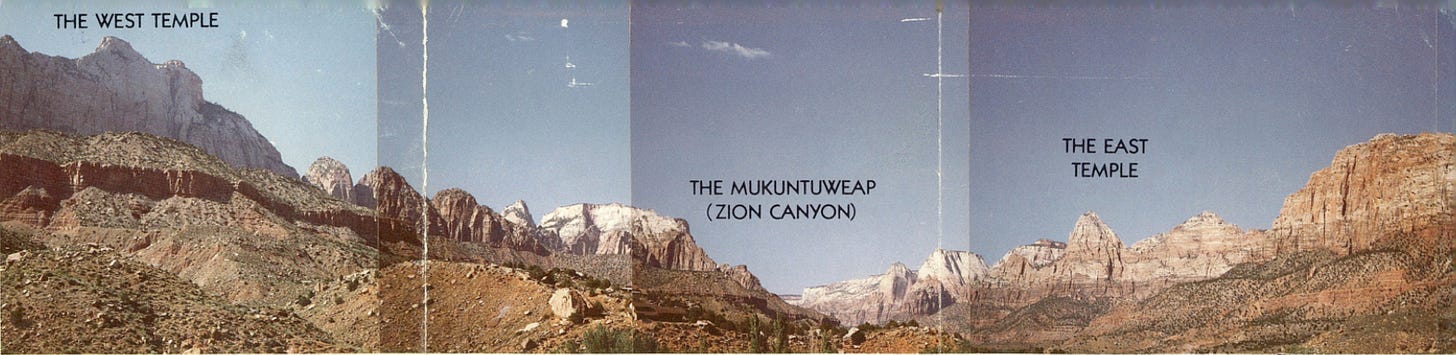

West and East Temple

In November 1933, using ropes and aided by “small rocks or pebbles wedged into cracks” as natural chockstones, the local Springdale brothers Norman and Newell Crawford climbed the West Temple, considered the “most impressive and majestic peak in Zion National Park”. After four hours of climbing from the valley below, they lit a traditional signal fire on the summit at 2 pm, then descended in two hours. A few months later, three climbers, equipped with only a 10m rope, became stranded on the descent when the first man down dislodged some of the crucial chockstones while descending, and the others “dared not make the attempt with such a pathetically inadequate rope”. Norman Crawford joined the NPS rescue team comprising eight people and “three ropes, totaling 160 feet” to rescue the two stranded climbers and continued on for the third reported ascent.

footnote: The fourth recorded ascent of the West Temple was not until 1963. In 1990, Springdale climbers Brad Quinn and Darren Cope took the local tradition further by climbing the first route up the West Temple’s 700m east wall, an 18-pitch bigwall climb requiring two bivouacs, calling their masterpiece, “Gettin’ Western” (VI, 5.10, A2). The route had previously been attempted by Bill March and Bill Forrest, who left a rack of his Titons (t-shaped nuts produced from 1973-1985) halfway up as a booty bonus. It was Brad and Darren’s first bigwall (Brad was a solid ‘Zion 5.10’ climber, i.e. hard 5.11 anywhere else).

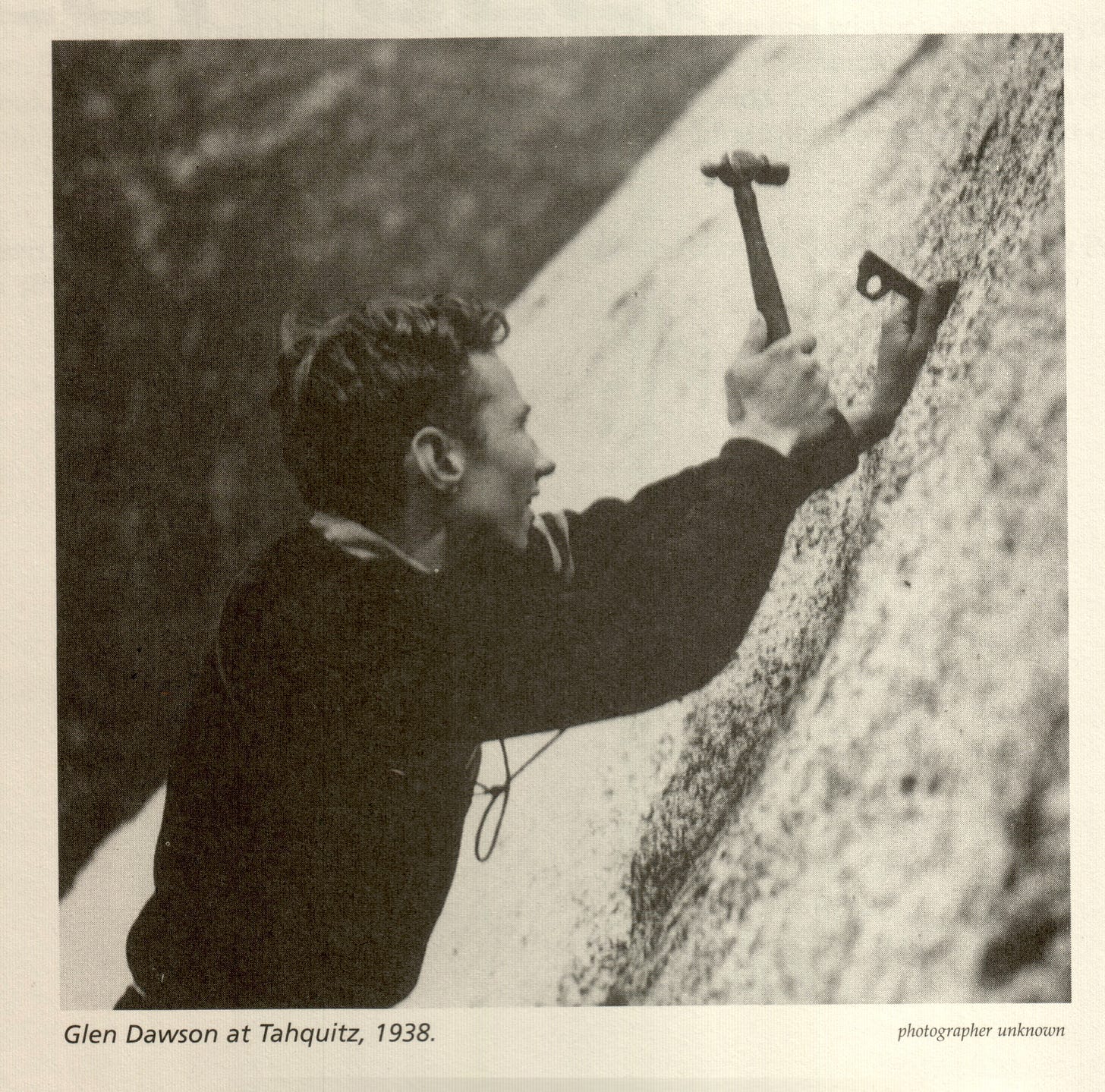

Glen Dawson (1912-2016)

Glen Dawson, a member of the Southern California Chapter of the Sierra Club, was the first to bring modern tools and techniques to Zion. Already an experienced High Sierra climber, in 1935 he climbed “about 30 routes” in the Wetterstein and the Dolomites with Theo Lesch, a ‘Munich climber’ and one of the “world’s best,” gaining further experience with piton-protected climbs, including the south wall of Marmolada in 5.5 hours, and the famous Herzog/Fiechtl route on the Schusselkarspitze (172nd ascent, see Volume 1 for the history of these global testpieces). In May 1937, Dawson climbed Yosemite’s Higher Cathedral Spire with Dick Jones, and in September climbed a new direct route up the East Buttress of Mount Whitney, using four pitons for protection and belays. In early October, Dawson led the Mechanic’s Route at Tahquitz using 16 pitons, a 3-pitch hard 5.8 noted as the “hardest prewar rock climb in the country” (Chris Jones, Climbing in North America, 1976).

Later in October, 1937, Dawson and Jones traveled to Zion and climbed the third recorded ascent of the Great White Throne with Homer Fuller and Wayland Gilbert (Jo Momyer accompanied the team but did not summit), and the next day set out to climb the East Temple, equipped with “tennis shoes, one 2-man rope (7/16" diameter, 90 feet long), one three-man rope (7/16”, 135 feet long), one rope-down rope (5/16”, 200 feet long), a piton hammer and two pitons.” On the summit, in the budding Zion mountaineering tradition, they spent the night on the pleasant forested mountaintop and lit signal fires near the rim for their audience below. They reported their climb as much more difficult than the Great White Throne, with the last ten feet involving a three-man stand (a courte-échelle) and noting, “It would be impossible for a party of less than three to get up unless it used different equipment.” The second recorded ascent of the East Temple, 27 years later (1964), involved a drilled bolt and eight pitons for the final climb to the summit.

Sentinel 1938

In June 1938 Dawson returned to Zion with Bob Brinton and climbed the Sentinel, only briefly described as “loose and treacherous, even for Zion” in the park service records. The second reported ascent of the Sentinel, in 1966, George Lowe, Dick Bell, Karl Dunn and Harold Goodro climbed it via the ridge rising from the Court of the Patriarchs. Lowe led the last pitch free, a traverse out to the right on a “two-inch ledge” with “practically no handholds” and “hundreds of feet of exposure.” The others on the 1966 team required pitons and aid with stirrups to climb the final part, reporting the last pitch to be the hardest in Zion (Dunn). They had no knowledge of Dawson and Brinton’s ascent nearly 30 years prior and believed they were the first to summit the Sentinel.

Authors Note: More Zion history will be covered in Volume 3. I have recently made all my Zion notebooks available online, covering the period from 1920s-1990s. Here is the link: http://bigwalls.net/JMZionNotebooks/album/index.html Note: These journals and notes are currently being shipped to the University Libraries at Utah State University, per their request as there is a lot of historical information of Zion climbing not available anywhere else. I lived in Hurricane Utah for many years and was a member of the Zion Rescue Team, being called out on a number of technical vertical rescues and many trainings. In the mid-1990s, they asked me to help organize the park’s climbing notebooks, a several-week project as the notes were in complete disarray and made finding information for climbing rescues difficult. I made several bound printed versions of the organized information, but unfortunately I did not keep one—one was left at the Rock House, and one at the NPS offices. The link above has copies of all the notes (all originals were archived by the NPS) but are not as organised as the notebooks I compiled for the Park Service! I also collected a lot of new information by active bigwall climbers in the 1990s (ps.,by the way Darren Cope who managed the Rock House, tells me the rock climbing haven that was the Rock House changed primarily because his relatives simply wanted to move back to that idyllic spot in Springdale. Sorry, Darren, about quote in Alpinist. I am still sad about the demise of Brad’s treehouse).

Bugaboos Note

Glen Dawson was a luminary of this new era of hard piton protected free (and occasionally a bit of aid) climbing, traveling far and wide to challenge his skills; in August 1938 made his way to the Bugaboos with his brother Muir, Bob Brinton, Homer Fuller, Howard Gates, and Spencer Austin (who wrote up their trip report in the 1939 Sierra Club Bulletin). Glen repeated Bugaboo Spire with the whole team, then climbed the second ascent of the Brenta Spire with Austin and his brother Muir, and the second ascent of Marmolata with Bob Brinton. Although not all climbs required pitons, the 1938 Bugaboos season proved that piton climbing was becoming more “transparent” in that climbers equipped with a few well-designed lightweight pitons, challenging long rock climbs in alpine conditions could be ascended efficiently and (relatively) safely. Glen Dawson was clearly in the vanguard of this developing style of mountaineering with his broad experience on the large faces of granite, sandstone, and limestone in North America and Europe.

Footnote: The team placed and also found at least two fixed pitons on Bugaboo Spire from prior ascents, including one on the Gendarme where Kain famously unsuccessfully tried to jam an ice axe, placed by Sterling Hendricks, Lawrence Coveney, Percy Olton on the second ascent (AAJ 1939). If Sierra Club’s team was indeed the third ascent as reported, then the piton Percy Olton reports finding fixed below the Gendarme in 1938 on the second ascent must have been placed by Conrad Kain on the first ascent in 1916, probably as a way to belay his client (see Kain sections earlier in this volume). But it’s unknown what type of pitons Kain would have been using in Canada, though I suspect they would have been ones he purchased at Mizzi Langer in Vienna.

Footnote: 1938 was a big year for the Bugaboos and among many repeats, seven new routes were climbed, in addition to Dawson’s team, by Percy Olton, E. Cromwell, F.S. North, L. Coveney, S.B. Hendricks, P. Prescott, M. Schnellbacher, Miss G. Engelhard, D.P. and I.A. Richards, C. Cranmer. Prior to 1938, there only appear to be three active years: 1916 (Kain/MacCarthy team/Frind/Vincent—three new routes), 1930 (Cromwell/Kaufmann/Kain—four new routes), and 1933 (Kain/Thorington—one new route).

Note: I am currently compiling Volume 2 of this series. The recent Substack writings are effectively drafts for Volume 2, (see Index here), and will be edited and incorporated into the final work.

As always, thanks for reading, and as always, comments are highly appreciated—just respond to this email (looking for more ‘blurbs’ for Volume 2 back cover!). Corrections or additions also highly valued! Cheers

I enjoyed reading this. I’m not a climber, but a daughter of Glen Dawson.

Wow. What a radddddical read, got me so incredibly excited to climb on sugar again! Thanks for details behind all this history. I can't imagine questing up those sand dunes without modern anything!