British Empire Pitons 1920s+, notes on Japan

Mechanical Advantage BigWall Climbing series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

“Though I am not one of those who believe that sin came into our mountain world when the first piton was planted in the Rock-garden of Eden, I sympathise with the traditionalists who feel that some of the romance has gone out of mountaineering now that the word "inaccessible' has been banished from our vocabulary, and who deplore the fact that any cliff can be climbed by those who have enough pitons and enough time to return every night to the foot of the cliff, and resume their engineering next day until a piton ladder is completed to the summit.” —Arnold Lunn, Alpine Journal, 1957

Acceptance of tools affects innovation.

Prior to WW2, pitons were not accepted as a standard climbing tool in the Commonwealth countries, including the UK, Canada, and New Zealand. Journal reports mostly covered the mountaineering accomplishments, with most excursions recommended for ascent with trained Alpine guides (two preferred). Pitons, carabiners and anchored-belay lead techniques were not essential for safe ascents of these mountains.

Much could be written about the changing attitudes toward climbing hardware in the UK, but because pitoncraft was not a proper mountaineering topic of discussion, there was limited shared information and ideas about their design and use; therefore the innovation story of the state-of-the-art technical rock climbing equipment—pitons and Karabiners—is muted for many of the Commonwealth nations during the 1920s-1940s period (footnote).

Footnote: don’t worry, the “clean climbing” gear story will be covered in how it fits in with the evolution of bigwall tools and techniques in the 1960s. The clean climbing story is well told at Stephane Pennequin’s Nutstory Museum (online). I hope to add to it a reference to “small pebbles wedged into cracks” to aid an ascent by Crawford in Zion on the West Temple in 1933 (TK). JW Fraser in 1916 is also reported to have used “innovative use of chockstones and threaded belays as a safeguard” and “scientific use of roping methods for safety on Table Mountain” in South Africa (AJ, 1978).

UK Attitudes

Attitudes towards artificial aids including pitons were mostly disdainful by British authors. For example (Peacocke, 1943):

“Many of the ‘Hammer and Nail Co.’ are bad mountaineers. In extreme cases the leader will drive in a spike and call on those below to pull (and) will repeat the process until his stock of ironmongery is exhausted. It would surely be more sensible if these mechanics took a portable windlass, or even a steam winch, and sufficiently long rope…”. —The Details of Rock Work.

Peacoke admits that “on a holdless face a piton may be thrust into a crack to make a belay”, but it was a slippery slope to begin to accept pitons as a protection tool for rock climbs, and local British climbers responded with outrage toward any pitons placed on home crags, such as on the “Munich Climb” in 1936, where a Bavarian team placed three pitons on a difficult route on Tryfan (now rated 5.6). The pitons were quickly removed, the climb done without their need, and another round of climber debate ensued. Six decades later the route was still used as a reference in Ken Wilson’s “Will rock climbing degenerate into theme park exercise?” article in the 1998 Alpine Journal.

Nevertheless, as a high standard of unprotected vertical rock climbing began to develop, this is not to say the British climbers did not appreciate the benefit of pitons on routes on the continent, with frequent reports of essential pitons in the early Alpine Journals, especially in the earlier years of piton-protected climbing. In 1912, a complete report of an ascent of Piz Badile, one of the more difficult technical climbs in the Alps at the time, is provided in the AJ, describing state-of-the-art piton use:

More examples: Lilian Bray and Ruth Hale

More could be written about the British women piton climbers of the 1920s and 1930s. It’s pretty clear when reading the tales in the Pinnacle Club Journal, and the Ladies’ Alpine Journal (unfortunately, no digital reference versions exist), that the women of the period were pretty game to go for the most technical climbs going at the time, and several pioneered new standards of bold mostly-free big wall routes (see Representation of Early Women Alpinists notes).

New Zealand

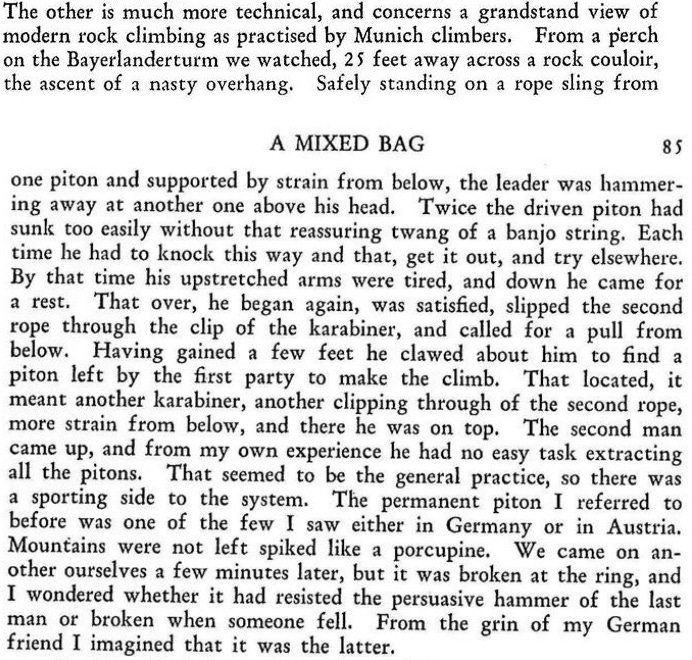

In New Zealand, with so many still-unclimbed high mountain peaks requiring advanced mountaineering techniques, pitons are hardly mentioned in the journals prior to WW2, and then perhaps only in the European Alps, not at home. Like in the UK, New Zealand “stories” about pitoncraft often clumped early bigwall climbers of the Eastern Alps as “Munich Climbers” with their techniques described as an awkward method of ascent (1937):

Canadian Challenges

One might imagine that because pitons were developed primarily on sedimentary limestone rock types of the Eastern Alps, then the mostly limestone Canadian Rockies would have also been a great place for pitoncraft to flourish. Not so. Unlike the steep vertical cliffs in Europe, the limestone/dolostone of the Canadian Rockies is much more broken and mixed with sedimentary shale layers, so the challenges involve primarily cold mountaineering techniques and strategies. There was generally not much middle ground regarding acceptable use of pitons between an occasion piton-belay anchor, and full-on piton-to-piton “winching”, so in Canada pitons were not welcome for the challenges at home. If a climb needed hardware, it was better to look elsewhere, and ascents involving known piton use—often by overseas climbers—were largely ignored in the early years, and even well into the 1950s. The exception to the rule was in the Bugaboos in the Purcell Range (Columbia Mountains), an exposed granodiorite batholith, more similar in geology to the steep granite of Yosemite than to the limestones of the Canadian Rockies. By the later 1930s, bold early big rock wall routes in the Bugaboos, only made possible with expert pitoncraft, were acknowledged and reported as very difficult climbs, with details of the techniques and the exact piton count published. But were these the first pitons in Canada?

The Canada Question

It is difficult to say when pitons were first used as points of protection for “modern” rock climbs in Canada. In 1916, Conrad Kain’s rock routes in the Bugaboo Group were the hardest and most technical in North America. Kain had first seen the imposing granite spires then called “The Nunataks” in 1910 during a survey of the Purcells with A.O. Wheeler, which he compared with the steep multi-ptich rock routes of his prior extensive piton-protected climbing experiences in the Alps (see Trains and Kain, part 2). Thorington writes of Kain’s first sight of the “magnificent spires” of the Bugaboos:

“Here were pinnacles and towers like the needles of Chamonix shooting toward the sky, their roots in a splendid glacier. This would be a battle ground; not only muscles, but all the tricks and art of climbing would be required. Conrad was thrilled, regretting only that time did not permit him to remain and attack them at once.”

In August 1912, after his work in the Altai Mountains, and on his way to New Zealand, Kain visited Vienna and purchased a new ice axe and other climbing gear at Mizzi Langer, where pitons were also sold. A gentleman’s guide in Canada at the time would never advertise the use of pitons, so it’s difficult to say without evidence whether he brought any pitons back to the Purcells for his routes in 1914 (Farnham Tower), 1915 (“additional climbs”), and 1916 (Monument Peak, Howser and Bugaboo Spires). But having previously seen these granite objectives, and with all Kain’s prior pitoncraft climbing in the Eastern Alps, combined with his devotion to offering the best (and safest) guiding service to his clients, it’s easy to imagine he would have appreciated how an occasional piton would be great insurance to keep his clients safe if there was no other natural anchor at belays (footnote). The Swiss guides, with their two-guide system—one guide always with clients at belays—would have likely have considered an artificial anchor to safeguard clients as cheating.

footnote: On the tricky Gendarme pitch on the south ridge of Bugaboo Spire, Kain laments there was no “projecting rock, or crack for anchorage.” A hammered piton was the most common “anchorage” for a crack.

In 1938, Percy Olton reports, on what was possibly the second ascent of Bugaboo Spire (as no record of an earlier repeat seems to exist):

“The next day we set out to repeat Conrad Kain’s climb up Bugaboo Spire, and repeat it we did almost to the last detail. We followed up the easy rock on the S. ridge to a point just below the first tower where we changed to rope-soled shoes. We then worked our way up the cracks in the face of the tower, finding a piton near the top to prove we were exactly on the route used before. When we came to the Bugaboo gendarme we pulled up short, as Kain had done, and looked for the easy way around which doesn’t exist.”

History would be clearer if more details of this piton were recorded, as many historians are fond of inspiring awe of early climbs noting the lack of comparative technical gear of today, so we often see, without clear evidence, the claim that Kain used no pitons on his Canadian climbs. Kain certainly came to Canada with the skillset to safely climb hard steep multi-pitch rock routes with pitons. Though it is not possible to say for certain if Kain initiated pitoncraft to Canada, the shift from guided to guideless climbing was no doubt influenced by his single-guide technique, and this in turn, drove the need to establish piton belays on long rock climbs, as the single-rope two-person system was more efficient for complex steep vertical routes.

Lightweight protection systems vs. perceived ‘tool-shop engineering’

In Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, it is true, that complex double-rope pure aid climbing techniques were being developed on the vertical and overhanging cliffs of the Dolomites, but there were also advancing standards of harder and more elegant mixed free/aid lines up steep rock faces, with lightweight pitoncraft protection systems. This new system of climbing hard multi-pitch rock climbs was ignored in many parts of the world, despite a vague awareness of the methods and tools, and of the remarkable routes that were being ascended. Nevertheless, pitons were key for a number of remarkable Canadian climbs in the 1920s and 1930s by overseas climbers, and these in turn led to further development of techniques for the greater bigwall challenges around the world.

Max Strumia (1896-1972)

In the 1920s, Massimo Strumia (later Max Strumia) began climbing in the Rocky Mountains of Canada. Strumia was an Italian/American climber who in 1920 migrated to the USA to study medicine, and who later published hundreds of scientific medical papers documenting new discoveries. Over his career, he travelled frequently between Europe and North America for both medical work and climbing. For his pioneering medical work in blood and plasma, he was awarded the Knight Cross in Italy, and a Presidential Citation in the USA (footnote).

Footnote: The first recorded use of plasma to save a life instead of whole blood was by Dr. Max Strumia in 1934. Dr. Amy Givler (my sister) looked over one of his hundreds of papers published before WW2: “This paper describes injecting plasma, which is the part of blood that doesn’t have cells (red and white blood cells). People who have lost a lot of blood need more volume. But in the field of war you can’t figure out what the person’s blood type is. If you inject the wrong type blood, the person will die of the mismatch. So he injected plasma which filled the soldiers’ veins again, saving their lives.”

An early member and contributor to the American Alpine Club (footnote), Strumia represented the AAC at the Congres International d'Alpinisme in Cortina d'Ampezzo in 1932. More than anyone else in the 1930s, with his multi-national climbing experience, Strumia raised awareness in North America of the new tools of climbing that had been developed in the Alps in the prior decades, with articles including, “Old and New Helps to the Climber” in the 1932 American Alpine Journal.

Footnote: Strumia’s “Moods of the Mountains and Climbers”, published in the very first American Alpine Journal (1929) is an inspiring article that captures the spirit of mountain climbing and being present in the mountains. Highly recommended! (this article should be read and referenced in any articles of Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow ideas, in my opinion, TK-more from personal journals). See also Hickson, AAJ 1931.

Born in Turin, Strumia started climbing in Italy and France when he was teenager, climbing over 70 mountain routes in the western and central Alps before moving to America. On his first trip to the Canadian Rockies in 1924, Strumia joined A.J. Ostheimer and J.M Thorington, who had engaged Conrad Kain for an expedition to Athabaska Pass, whereupon they climbed a number of significant first ascents.

These summits involve significant challenges to find suitable routes to access the range, and were primarily climbed with mountaineering techniques (moving rope belays for exposed and crevassed areas, moderate rock climbing, chopping steps in steep ice, etc.). Strumia was also involved with the scientific mapping of several complex high-level glacier routes that weaved within the Canadian ranges, such as the route from Jasper to Field, and during these tours and on other expeditions, he racked up a considerable record of climbing in the Canadian Rockies.

Strumia was also drawn to the steep multi-pitch rock faces of the Rockies and in the 1920s summers, he climbed in Canada with Thorington, Kain, and other guides, followed by a number of successful trips with his “perennial companion” Bill Hainsworth (AAJ, 1972). Strumia’s routes often involved the modern piton climbing techniques; on a new route attempt on Mt. Robson in 1930, he placed two pitons, and in the Sunwapta Valley, on a mountain briefly named Piton Peak (footnote), Strumia notes, ‘The rotten snow-covered rock proved difficult. It was negotiated with the aid of three pitons and safety snap-rings, and provided a highly exciting climb for the leader and a cold one for the lower end of the rope.”

Footnote: “Piton Peak” was later named Mount Englehard in 1966, after American mountaineer Georgia Engelhard. See also, “Climbs in the Canadian Rockies, 1926” (Alfred Ostheimer) in the December 1927 The Geographic Journal, published by The Royal Geographical Society, and AAJ 1931, AJ 1933, CAI 1926.

Mt. Oubliette (Strumia/Hainsworth/Fuhrer)

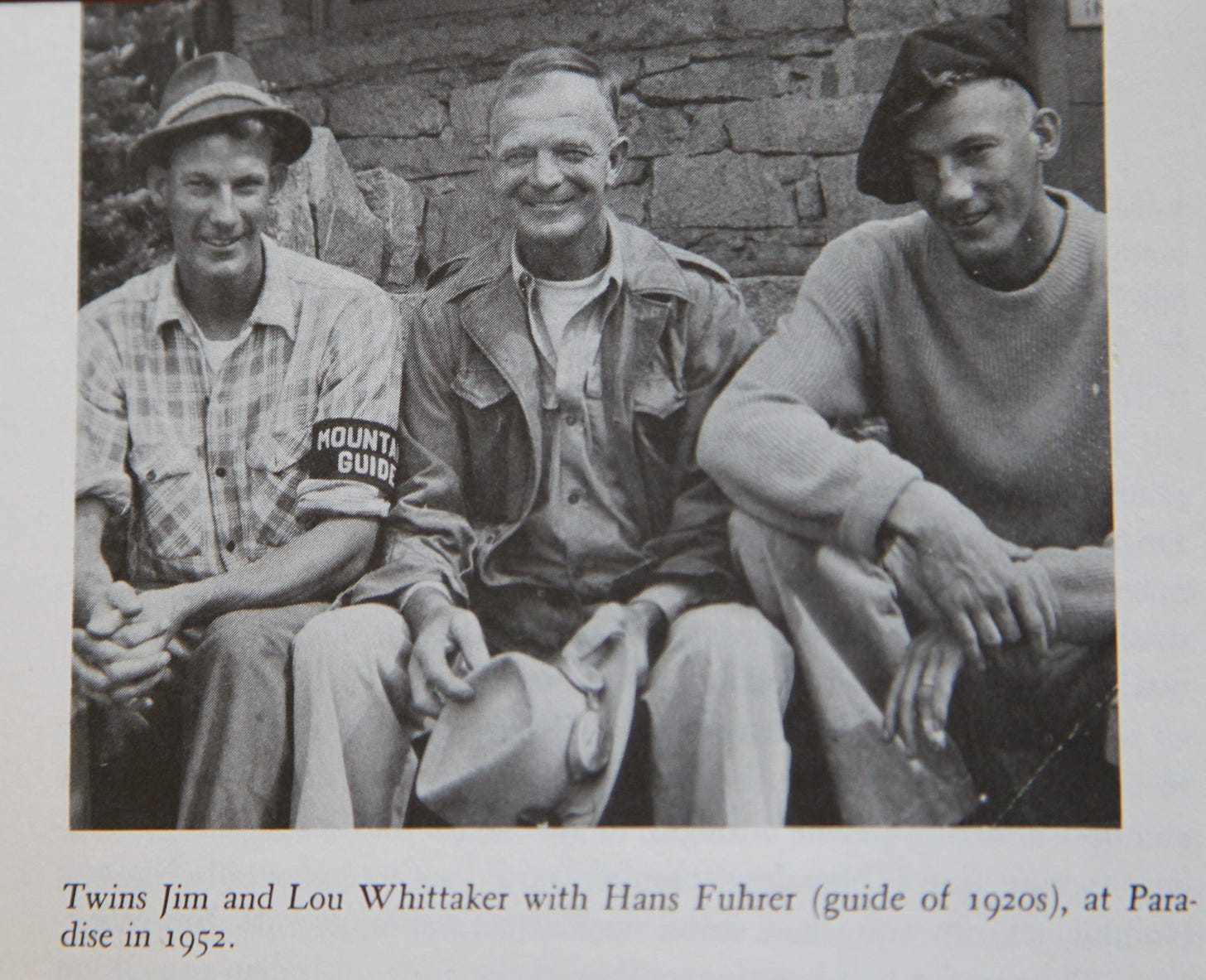

Strumia and Hainsworth, with the guide Hans Fuhrer, climbed the first ascent of Mt. Oubliette in 1932.

It is listed as “unnamed” in the 1940 guide, noting “piton and ring”, and although this climb does not appear in many (any?) modern Canadian climbing histories, the 1932 American Alpine Journal noted it as “surely one of the most difficult of the whole chain” of the Rockies. The 1933 British Alpine Journal devotes eight pages to the ascent as one of the more difficult technical ascents in North America at the time. In addition to describing their tactical use of pitons to make the ascent possible, Strumia and Hainsworth’s report also provides one of the first clear descriptions of how pitons were used as an emergency retreat tool:

There is a lot more that could be added to Strumia’s story (footnote), as he is one of the most interesting early members of the American Alpine Club. Strumia documented his climbs in Italian, American, and Canadian, and other international journals, and his sharing of advanced tools and techniques of climbing clearly influenced the development of bigwall techniques in North America. By globetrotting between Europe and North America, climbing the ‘testpiece’ routes on both continents, Strumia was both learning and sharing all the latest developments and exciting adventures to be had.

Footnote. J. Monroe Thorington, chronicler of Conrad Kain, wrote the obituary for Max Strumia in the 1972 American Alpine Journal, and includes an extensive resume of climbs in the European Alps, including the Grandes Jorasses. Although Thorington sometimes referred to piton techniques as siege tactics, he participated in several cutting edge climbs of this caliber: “There they were turned back by a succession of broken towers, which will require more time, much rope and special technique if they are to be overcome. We were unprepared for long siege tactics. As it is, several pitons now grace this ridge. On the following morning we left for Fortress Lake.”(report on North Wing of the Columbia Group and other writings of Thorington.) James Monroe Thorington, who was president of the AAC from 1941-1943, was noted in 2002 by past president Jim Frush (who I served under as AAC board member) as “the ultimate scholar of alpinism for the Club and involved in producing a long series of guide books for the Club.”

NEXT:

In the United States during this same period (1920s-1940s), a greater openness to the acceptance of the new tools led to a steady pace of development using advanced materials to create lightweight climbing tool innovations, which helped advance global bigwall climbing standards. This will be covered in the next posts, starting in the 1920s, and leading to the world’s most advanced climbing tool designs by the 1950s (outlined here).

Postscript: First documented pitons in Canada

Ok, so when were the first climbing pitons used in Canada for a cutting-edge climbing objective? I posed this question to Chic Scott, who has written the most complete history of Canadian climbing, and he responded:

“There is an instance of Frank Smythe using a piton on Mount Colin near Jasper about 1947, (a topic of discussion at the time, and published in Smythe’s 1950 book, Climbs in the Canadian Rockies). The first ascent of Brussels Peak in 1948 by two Americans involved a number of pitons and some bolts. It aroused quite a reaction. The old-time ACC folks in Canada were very opposed to pitons. You should take a look at "The Ascent of Dumbkoff Tower" by Bob Hind in the CAJ.” (footnote)

Footnote: Bob Hind appears to be a rival to Max Strumia, both seeking similar kinds of steep rock objectives in the Canadian Rockies in the 1930s. In 1936, they both attempted to climb first to the summit of Brussels Park as members of separate teams, Strumia’s team utilizing pitons. It is not clear whether Hind actually used pitons on his routes even as he condemned them in story.

I wrote back and reminded Chic of the celebrated 1940 bigwall ascent of Snowpatch Spire in the Bugaboos, with significant attempts in the late 1930s, which, perhaps along with Waddington, were the early cold weather proving grounds for the bigwall techniques being developed in Yosemite at the time (these and more vista-opening bigwall lines around the world will be covered in future posts).

Chic wrote back:

“It seems likely that the 1938 climb on Bugaboo Spire involved the first use of pitons in Canada. I think Tony Cromwell and Georgia Engelhard climbed in the Bugaboos before 1938 (referred to in the article cited above) but I have no idea what they did or if they used pitons.”

As someone always more interested in the big rock walls of the world, my knowledge of big mountains is peripheral, though I knew of the 1925 routes on Alberta as one of the first big rock routes on a big mountain, as it is covered in Steve Roper and Allen Steck’s Fifty Classic Climbs of North America which I read countless times when I was actively climbing, so I dug in, and eventually found a reference to pitons used for descent in Thorington’s very brief 1940 guidebook description of Mt. Alberta, first climbed in 1925 and had not yet been repeated:

Mt. Alberta (11874’): 1925 first ascent by S. Hashimoto, H. Hatano, T. Hayakawa, Y. Maki, Y. Mitai, N. Okabe, H. Fuhrer, H. Kohler, J. Weber. From camp on meadow (6800') at head of Habel creek, via S. and E. slopes and central portion of E. face to extreme N. end which is highest point. (Loose rock and falling stones; a night was spent at 11000'; four pitons used in roping-off during descent; upper 1500' of the mountain difficult.) Ascent: 16h; descent: 16h.

footnote: In 50 Classic Climbs, Roper got the first names of Hans Fuhrer and Heinrich Kohler reversed, apparently, and this mistake comes from the James Weber report of the climb translation. When Roper and Steck published their dream guide (1979), the route had only been climbed perhaps ten times and was rated IV, 5.6. Ten pitons and ten chocks, as well as ice axes for the summit ridge, were recommended for Mount Alberta, Japanese Route.

These “roping-down” pitons are also referenced in an article in the CAJ by John Oberlin, providing for the first time in 1953 a translation of guide Jean Weber’s account of the 1925 first ascent. Pitons might have also been used for the ascent, it is not clear, as this route and others were ignored in English media for decades (footnote). But we now know that Yuko Maki, who led the expedition, was one of the best technical climbers in the world at the time, and that Japanese climbing technology was highly advanced.

Footnote: Noted Canadian climbing historian Zac Robinson tells the story in a nutshell: “I have climbed the 1925 route ... and it's loose; ha! Interestingly, it's Thorington's guidebook -- the first edition (1921) -- that lures the Japanese over in the first place. In that edition, Mount Alberta features as the frontispiece, and under it the alluring caption, "A formidable unclimbed peak of the range." The complete disregard of the Japanese ascent in the 1925 CAJ (it receives a one-line statement of fact in the back matter) says volumes about the ACC in the 1925. Racism, unquestionably -- but the use of those four pitons would have been looked-down-upon, too. One has only to read about what CAJ contributors were saying about pitons a decade or more later, in the 1940s and 50s, to see how entrenched those prejudices were (See R.C. Hind's "The Ascent of Dumkopf Tower" [CAJ 34, 1951] - a parody on the first ascent of Brussels Peak). Frank Smythe was leading the anti-piton charge in those days... despite having to use a piton himself on the first ascent of Mount Colin, which he claimed he always "regretted." (email 16/6/2022).

So there you have it, the first known pitoncraft in Canada in 1925, for “roping down” Mount Alberta. There are many stories drawn from Mount Alberta; highly recommended: Marilyn Cambell’s story on the Alpine Club of Canada’s website: ROCKIES HISTORY: MOUNT ALBERTA'S SILVER ICE AXE

Conclusion

Often in history, the “first ascent” is widely celebrated, the attempts forgotten, and thus only a rough history is told. First, biggest, tallest, greatest, etc. are good headlines, but can get pretty boring after a while, as such records are quickly broken (though it is fun to have a “record”, even if short-lived). When you look deeper into climbing history, and especially in the realm of technological achievements—the use of most lightweight tools to optimise the elegance of an adventure—the attempts and forgotten climbs are often the real breakthroughs in terms of tools and techniques, and directly lead to the later success. The equipment innovation understory leading to the most elegant bigwall lines in the world is what my series is all about. Thanks for reading! —John Middendorf

FUTURE CHAPTER: Climbing technology developments in Japan—notes:

The story of gear development in Japan has never been fully told in English, and this field of research could benefit from a bilingual researcher with knowledge of the engineering aspects of climbing technology. My friend Naoe, who I know has always had a sharp eye for the most cutting-edge climbing tools (as he ordered over 100 A5 Portaledges from me back in the 1990s for his Lost Arrow distribution business;) has been helpful in providing info, and I have collected a few of the only resources in English (e.g. the Japanese Alpine Centenary 1905-2005, celebrating 100 years of one of the earliest national alpine clubs in the world), but there is very little translated or public material on the innovators of equipment made in Japan. My hunt continues as I look for translatable resources (Sanko, Sangaku, Japanese Alpine News articles on technology, 1900 expedition to the Karakoram, etc.). I am especially curious as to when the first climbing hardware was produced in Japan, and using what materials. In the meantime, a few tidbits:

Appendix

Ok, I am going to use my "made-up" word: bigwall instead of big wall. Kris gives me the go-ahead: https://explorersweb.com/big-wall-climbing-what-is-it-which-wall-is-the-biggest-and-why-is-this-climbing-different/

getting messages like this from writers of history really makes my day!

"Strumia is fascinating. I can't wait for the Japanese section. Maki is a very interesting figure. Thanks John, Mechanical Advantage is one of my favourite reads!--David Smart"