1950s USA Gear notes

Mechanical Advantage series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

This page will be updated (draft, jumping ahead a bit in my timeline…)

Key concept: Starting in the late 1920s, American piton production began a steady evolution, piggybacking on new developments in the USA steel industry, leading to the high alloy steel pitons of the 1950s which in turn led to opening the doors of Yosemite’s big walls, and to visionary big wall climbing elsewhere on the planet.

The well-known as the “Golden Age” of Yosemite climbing, noted by historian climber Steve Roper as the quarter-century between 1947-1971, when many huge technical big wall routes in Yosemite were first climbed, was an accumulation of many new tools and techniques merging at the time. There are many great online collections of mostly post-WWII pitons and other mainstream equipment of this period, but the exact chronology of hardware is sometimes unclear. In the age prior to the widespread use of clean climbing protection, piton craft was an essential art for hard rock climbs; this post is an attempt to add further detail in the chronology between the 1940s and 1960s (still working on the 1920s-1930s history for the origins of USA-made piton design—as I mentioned in the last post covering the major European climbing gear in 1964, it helps to know where we are going to understand the initial steps in that direction).

The 1950s

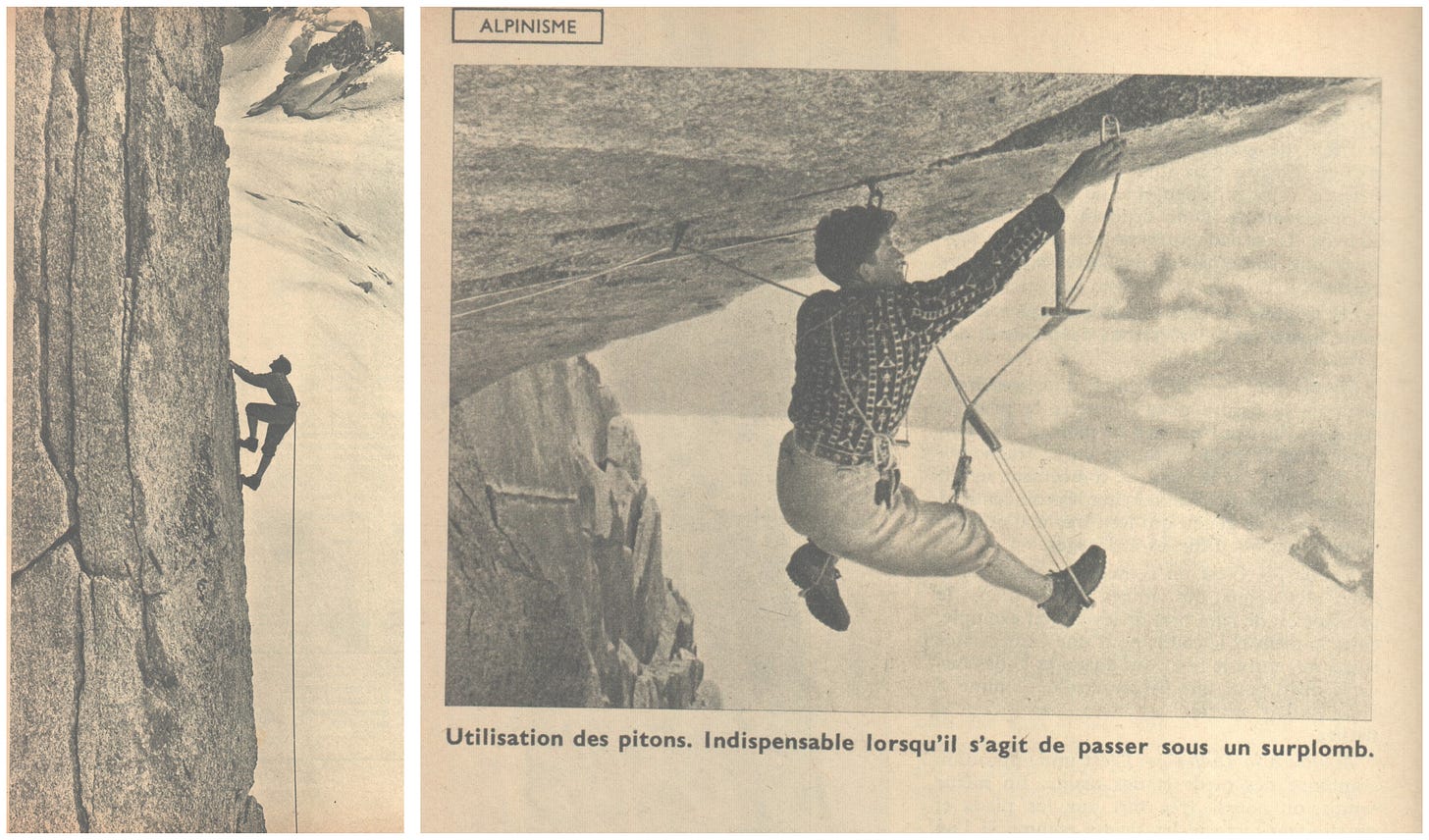

In Europe in the 1950s, climbing had become a mainstream sport, and heroes appeared regularly on the covers of national magazines. The legends of climbers needing to forge their own pitons prior to a first ascent had long passed, and there were a number of manufacturers competing for market share by offering wider availability of relatively inexpensive, mild steel pitons of varied design. Pitons were mostly the “vertical” and “horizontal” designs developed in the 1910s, now with dozens of design variants and thicknesses, though the largest pitons on offer were suitable for only about the size of a fingertip—anything bigger was thought climbable without protection, though wood wedges (“coins de bois”) were sometimes used for larger cracks if aid was required. And of course, bolts were becoming more common (bolting technology will be covered in a separate post).

Though most European mountaineering equipment in the 1950s was mass-produced as mature products, in the 1950s USA, a blacksmith-driven period of innovation was about to begin.

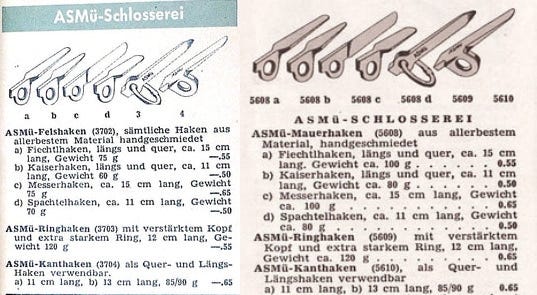

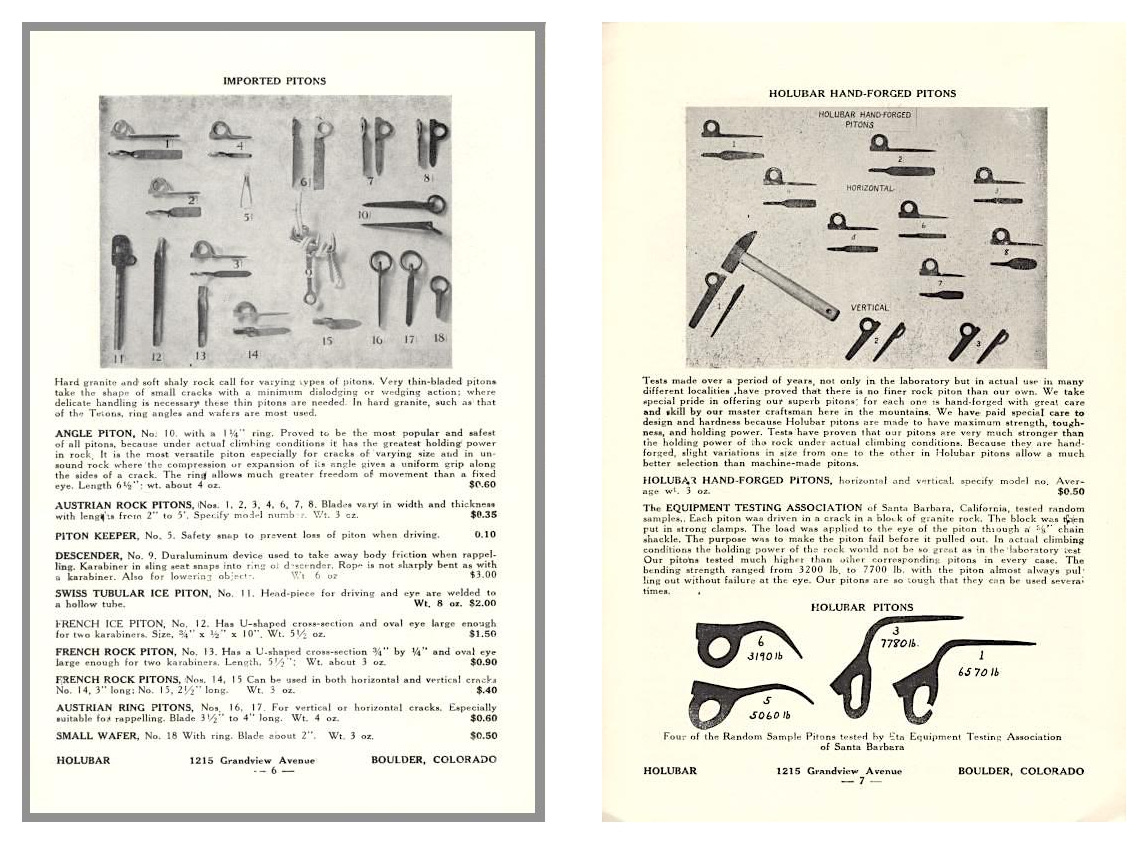

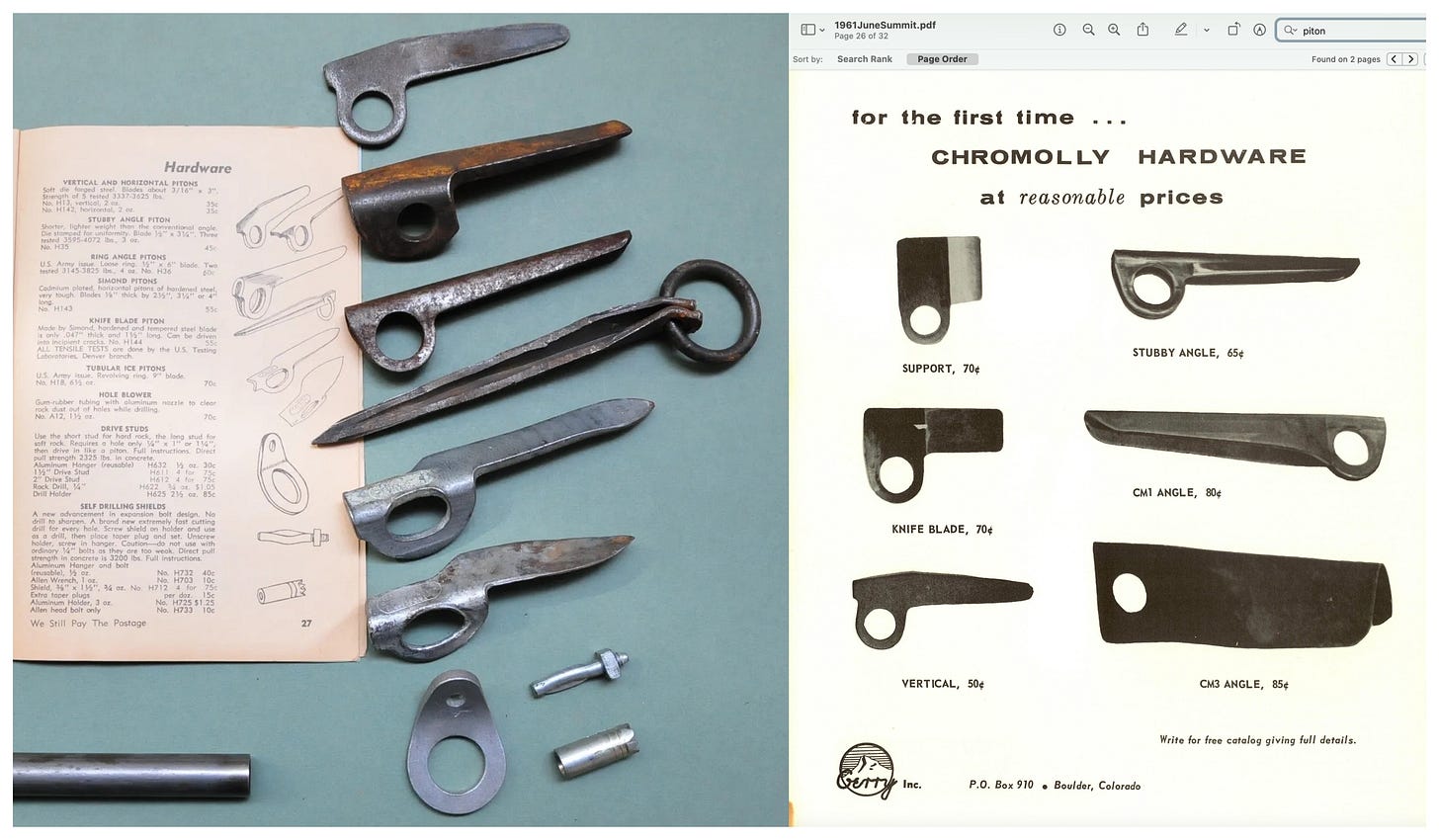

In the 1950s in North America, most pitons used for climbing were made in Europe, where the fullest range of size and price options were available. There are a number of references of climbers buying equipment from Sporthaus Schuster in Munich, including the ASMü pitons (produced by August Schuster) used by the Stettners on Longs Peak in 1927 (story next post). Some of the highest quality pitons came from Switzerland, though these were only available in the USA from specialty retailers such as Abercrombie & Fitch, who were selling pitons made by Hupfauf. Fritsch and CCB also produced quality pitons in Switzerland. The Swiss pitons appear to be made from higher grade steel than the typical mass-produced mild steel pitons from the major post-WW2 brands: Cassin, Simond, and Charlet Moser, and Stubai, but further metallurgical analysis would be needed to confirm this. Throughout Europe, there were still a number of smaller manufacturers creating custom pitons for climbers, all using various grades of mild steel, but store-bought pitons were plentiful and relatively cheap, so they became the mainstay of a climber’s ‘rack’ of gear.

Quick Review of Steel

Most pitons made in Europe, well into the 1960s, were made from mild steels. Engineers and climbers have all sorts of confusing names for steels with various amounts of carbon, such as low-carbon/low tensile steel, 10/10 steel, ST37 (Europe), ‘sweet homogeneous iron’ (Bonatti), etc. (“soft iron” is a long-standing misnomer, as the pitons are steel, not iron). Mild steels (SAE 1000 series) are relatively soft and malleable with a maximum hardness of around Brinell 120, so not suitable for super-thin pitons (as they will buckle) or for angle pitons (as will tend to flatten out when getting hammered into a crack). But for the mainstream mass-produced “horizontal” and “vertical” piton designs optimized for the limestone cracks of the Alps, mild steel is strong and robust enough for a few placements, and was suitable for a low-cost piton.

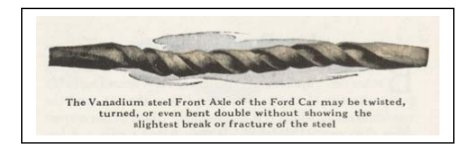

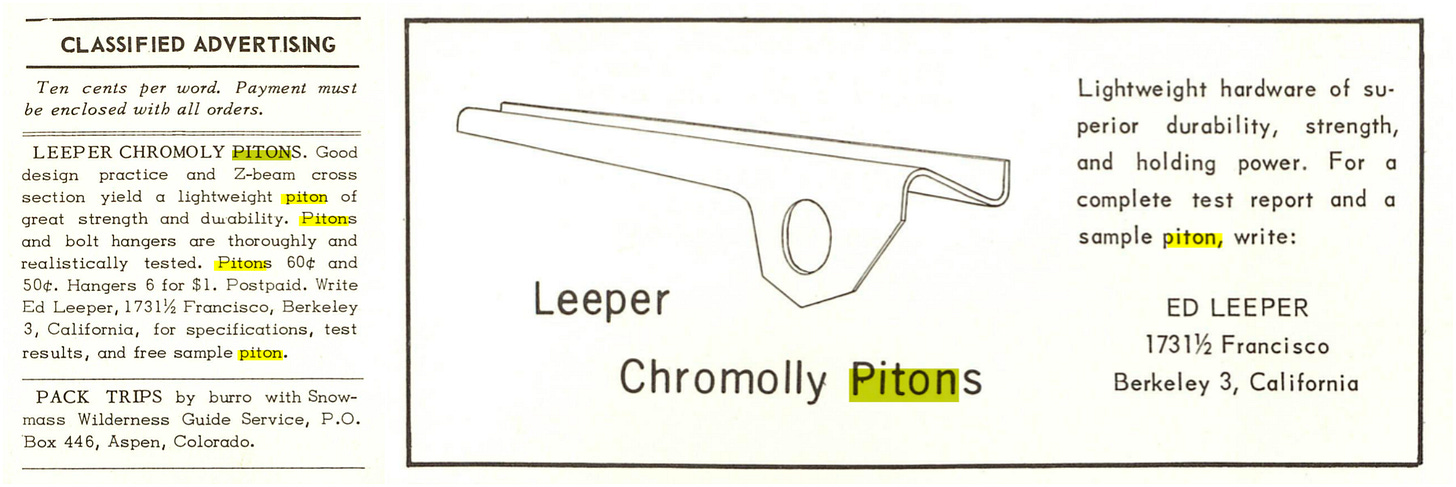

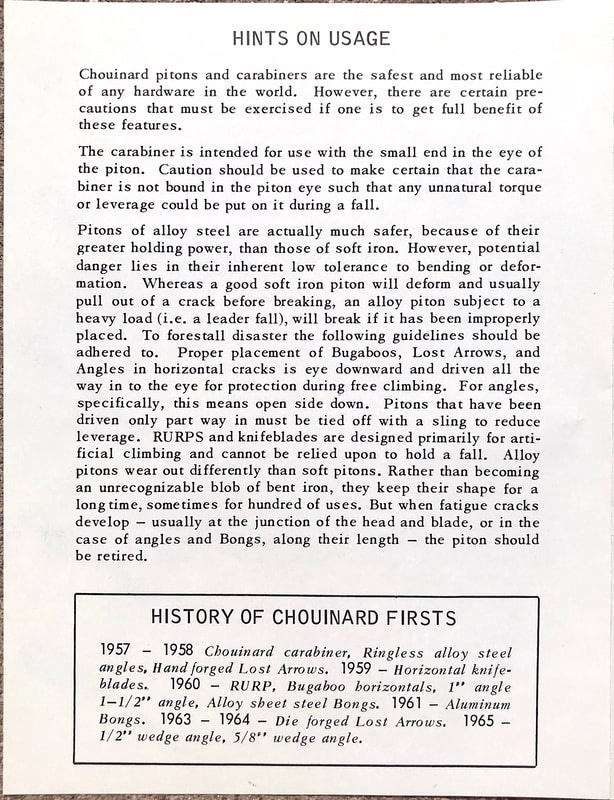

High-strength steels used for pitons also have a number of names, Chromium-Vanadium (CrV), Chromium-Molybendum (ChroMo, Chromoly, etc.), as well as many other alloyed steels. Alloys steels like these can be hardened to Brinell 300 and still be tough (RC41/42 makes for a nice knifeblade piton hardness).

For the purposes of steel climbing pitons, perhaps it is easiest just to refer to the original steels used for climbing pitons as “Mild Steel”, and higher strength piton steels as “Alloy Steel”, with alloys such as chromium, vanadium, molybdenum, etc. in just the right trace amounts enable the steel to be stronger and harder by optimising grain structure with heat treatments, which fine-tune the hardness and toughness—the measure of bend before breaking/ductility—of the steel, which are inversely related for a given type of steel. More on 20th century global steel evolution here.

There might be other types of steel used in the evolution of pitons, perhaps we can call them “Medium-Strength Alloy Steels” to differentiate from the more common high-strength alloy steels available today—steels with a higher degree of hardenability than mild steels with good toughness properties and with some alloying elements, a developing science in the 1930s-1940s. I believe most climbers of this time could intuitively differentiate when pounding different types of steel pitons on their racks from various sources, though knowledge of the types of steel was often not shared between manufacturers and nations. USA steel producers became the world’s largest in 1901, and for the next five decades were global leaders in high-strength steel research, driven by the automobile and aircraft industry. (See also Simcoe). It appears that some of the early USA pitons were made from higher quality steel than was commonly used for pitons in Europe at the time. It is not unthinkable that a blacksmith’s simplest source for high-grade alloy steels was from abandoned industrial parts like the crankshaft of an old Ford (it is still a point of pride among backyard blacksmiths to repurpose metal parts and tools). After WW2 in USA, many new alloy steels with a wide range of properties became more common and were used for small batches of pitons and other parts by the occasional crafty blacksmith among the climbing community.

Rough Material Chronology

So with that in mind, here is the rough idea of steel piton material evolution:

1900-1960s Europe—mostly mild steel pitons. Some of the early Swiss pitons (1930s+) might have been made from higher quality European steel than commonly used mild steel for most pitons at the time.

1920s-1940 USA made pitons: mostly mild steel, though some pitons made in smaller quantities might have been made from medium-strength alloy steels (Dwight Lavender and Bill House pitons TK).

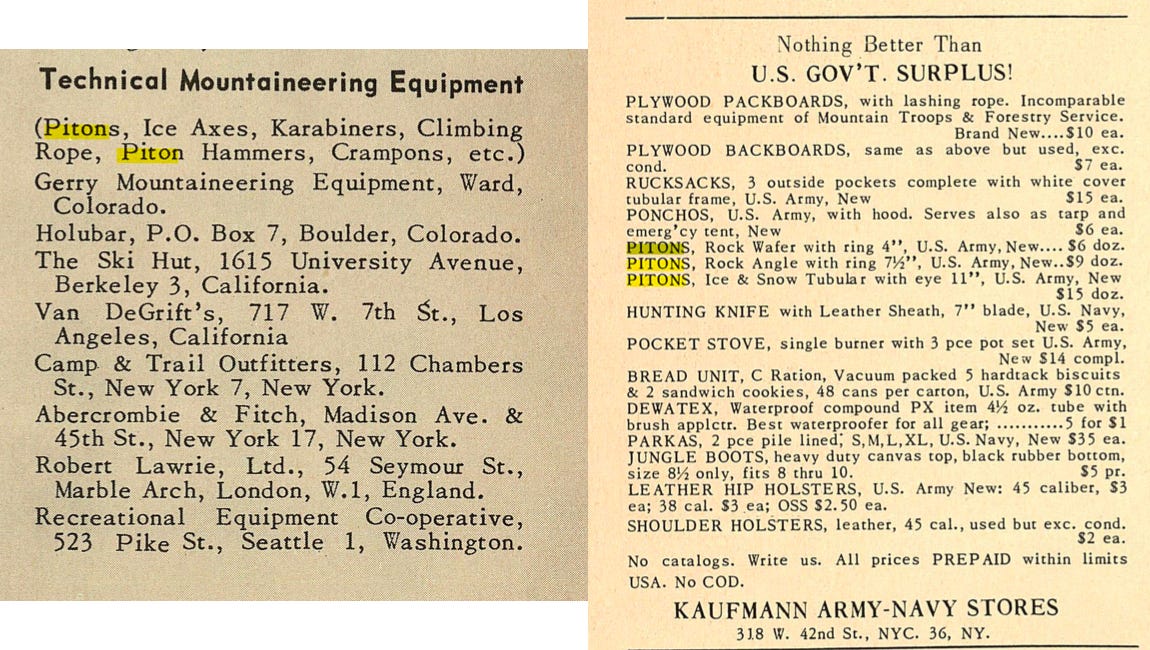

1943: US Army mild steel ring angle (probably 1020), vertical and horizontal pitons. Tens of thousands of these were made for anticipated mountain warfare, and unused stock flooded the market in 1946.

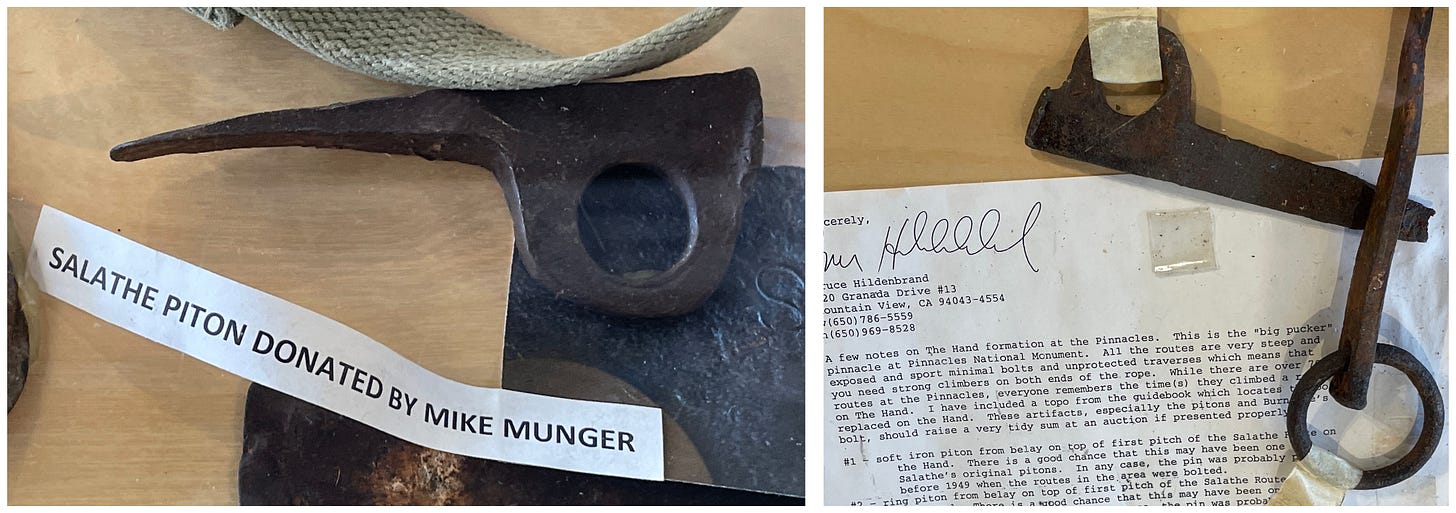

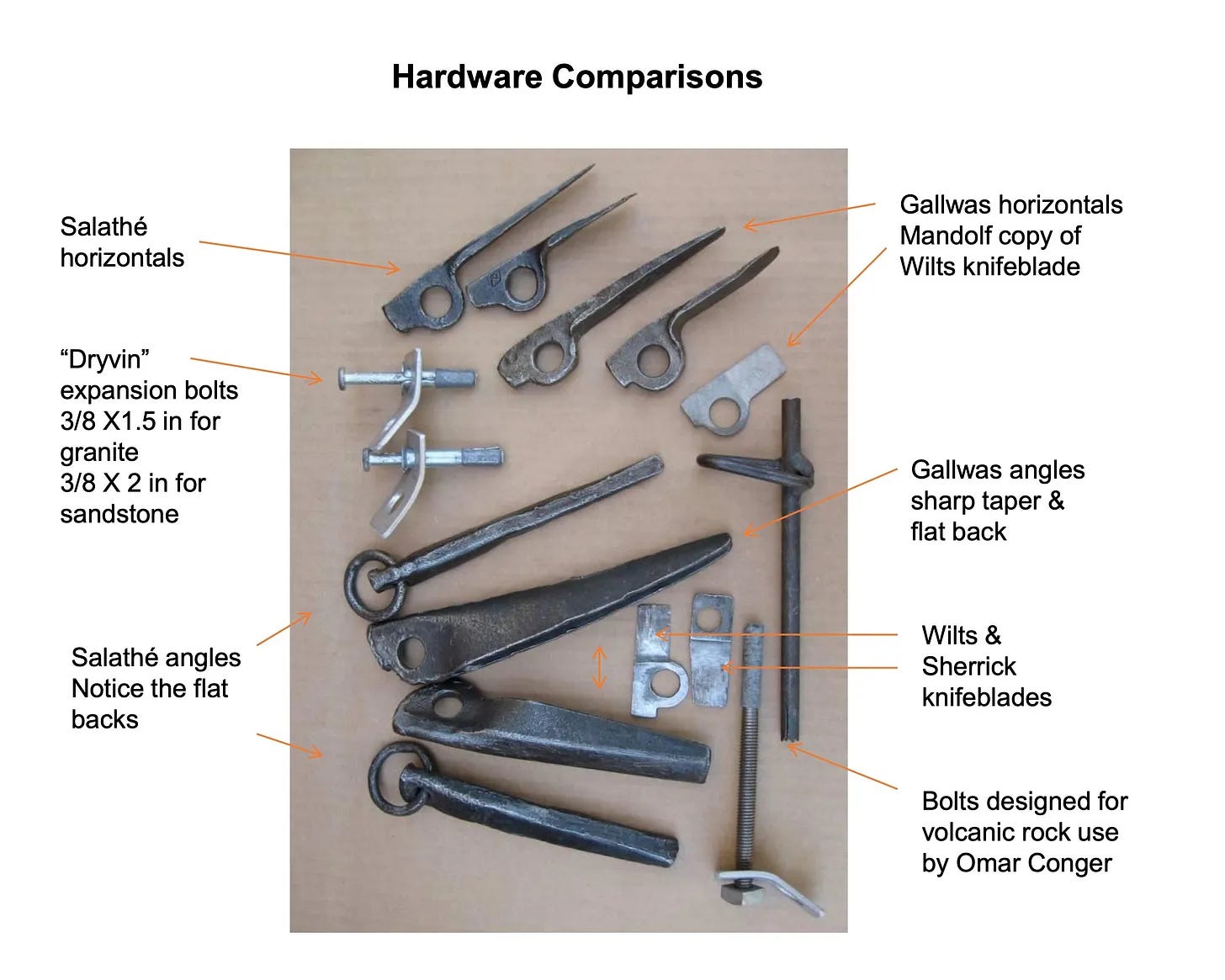

1943 US Army pitons made from mild steel. Not many of the Army horizontals seem to survive. Note also the reference to “soft iron.” Image courtesy Karabin Climbing Museum ~1946: John Salathe uses high-strength Chromium-Vanadium (CrV) alloy steel to make pitons for his climbs in Yosemite. CrV can be hardened precisely with heat treatment, quench, and tempering to get the optimal balance of toughness, hardness, and strength.

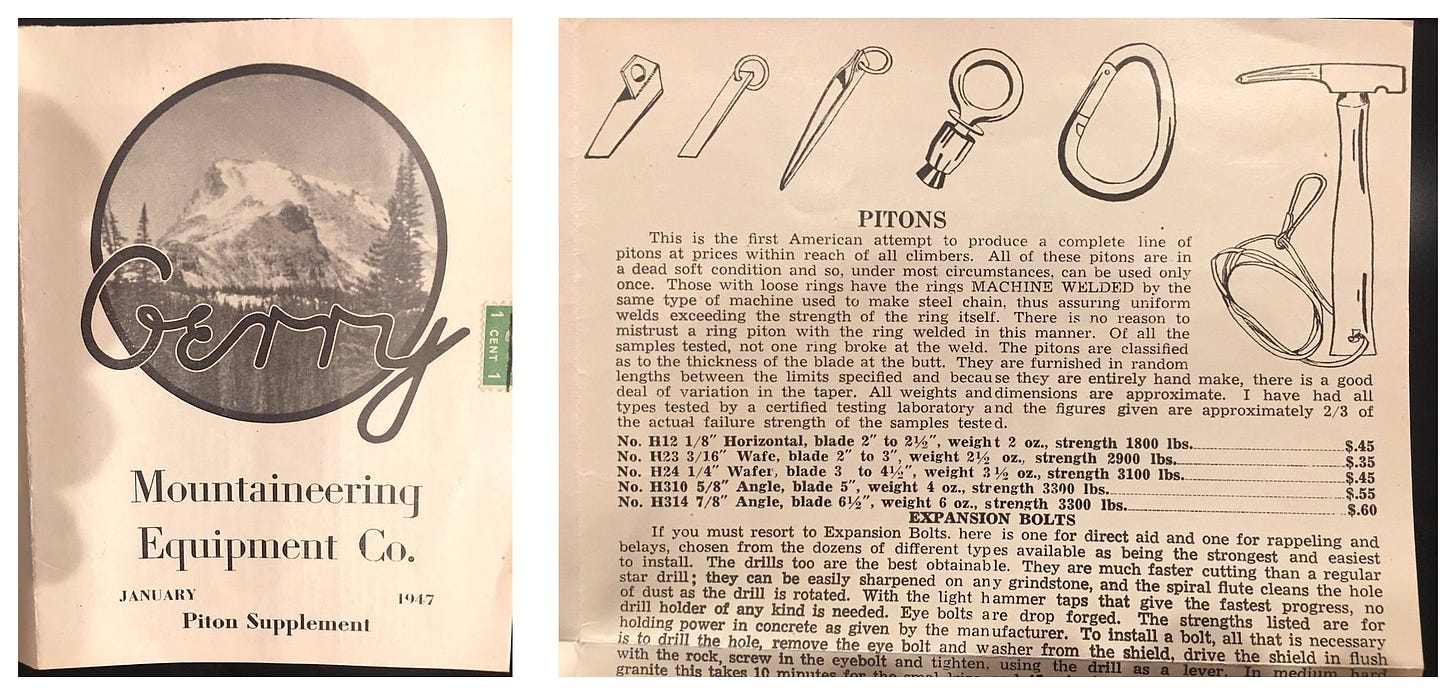

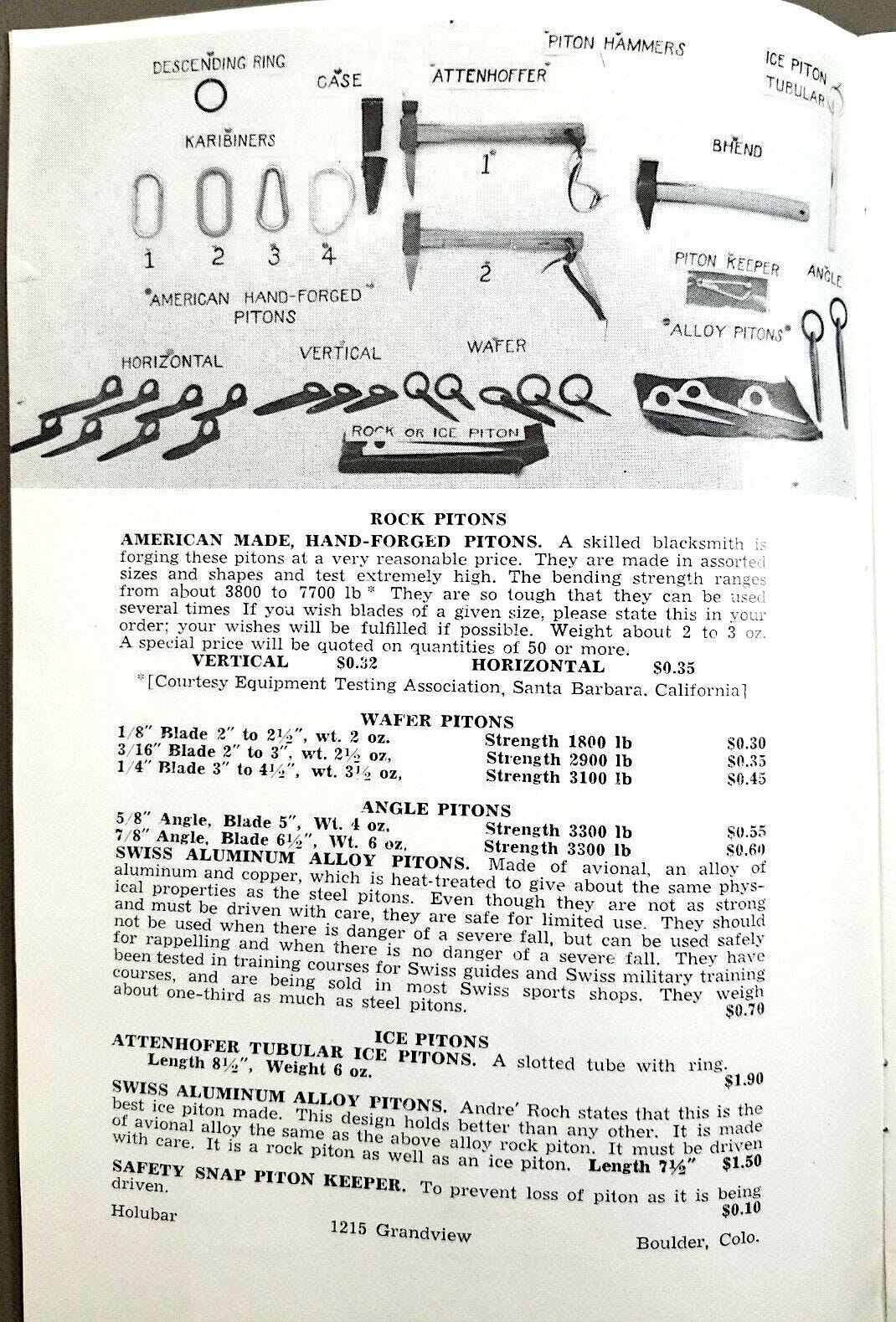

1946-1954: in the USA, Bob Owens (Kachinas), Bob Bruning (Holubar), and Norton Smithe possibly also made pitons with a medium- or high-strength alloy steel in this period.

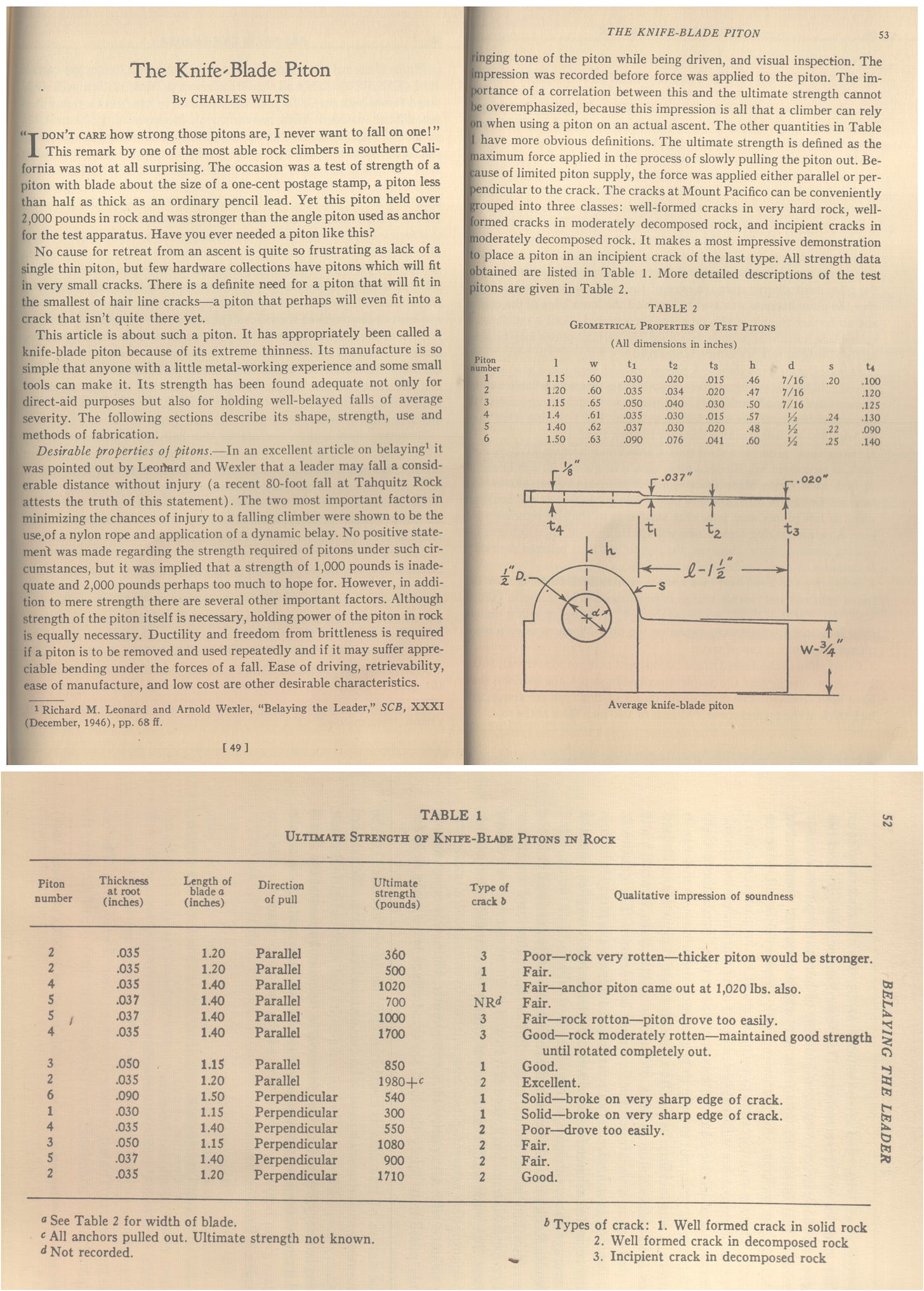

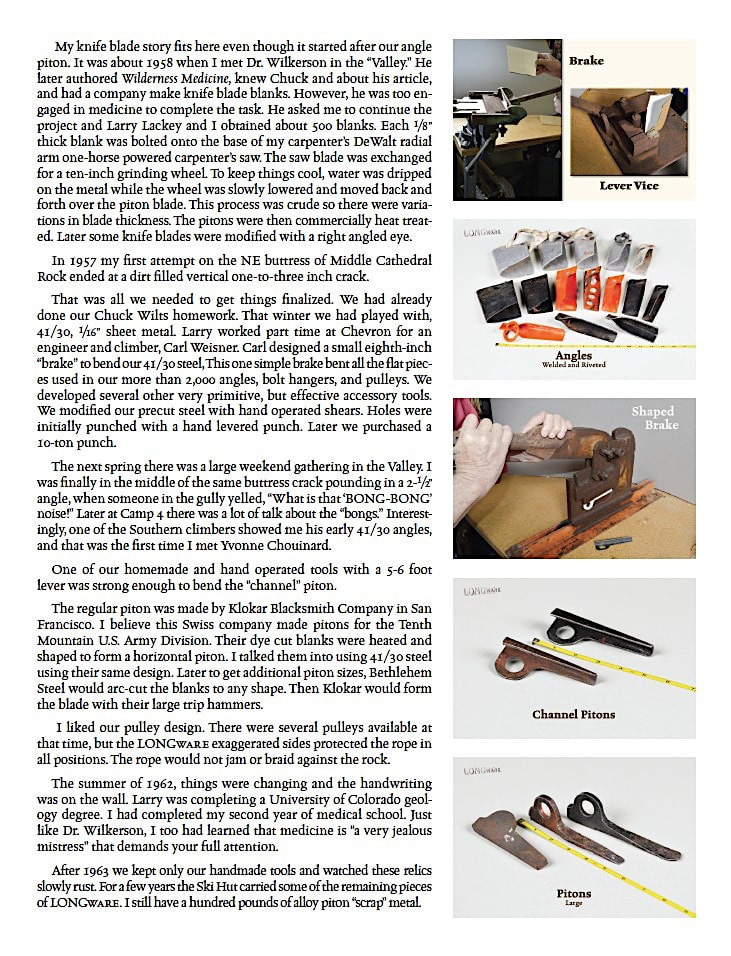

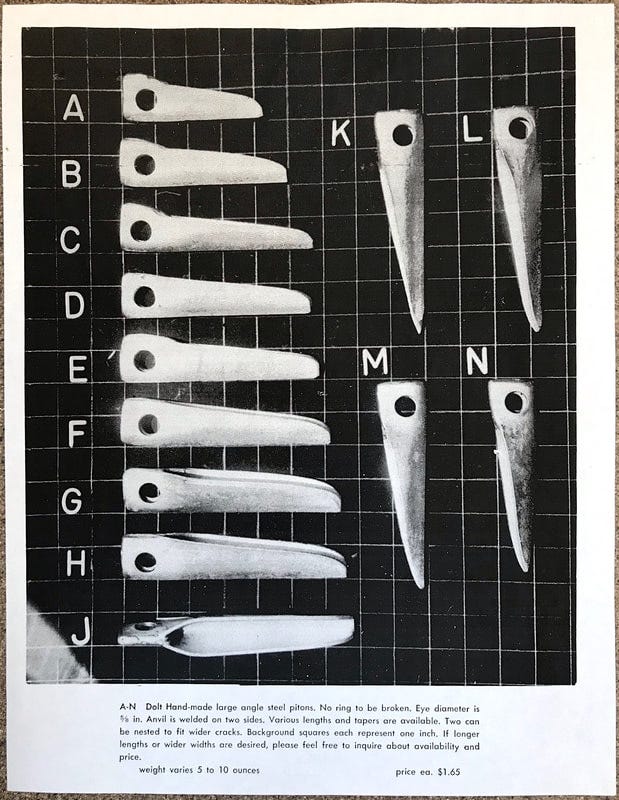

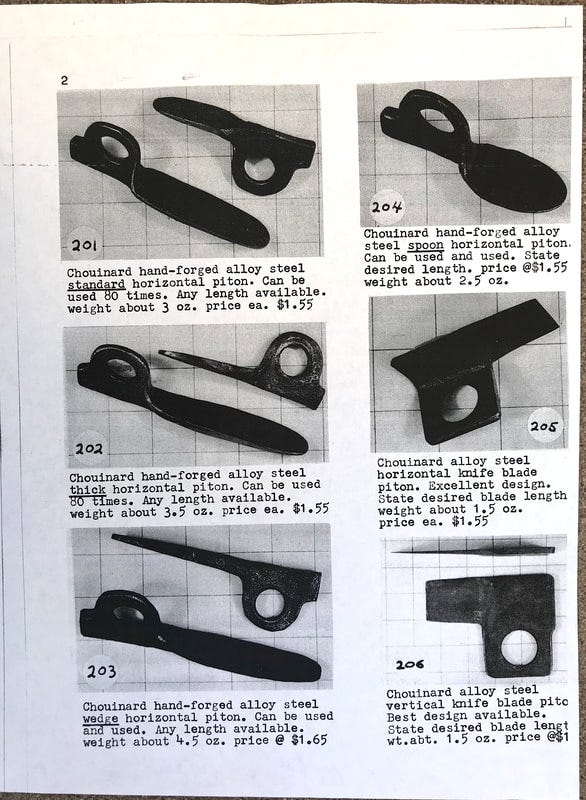

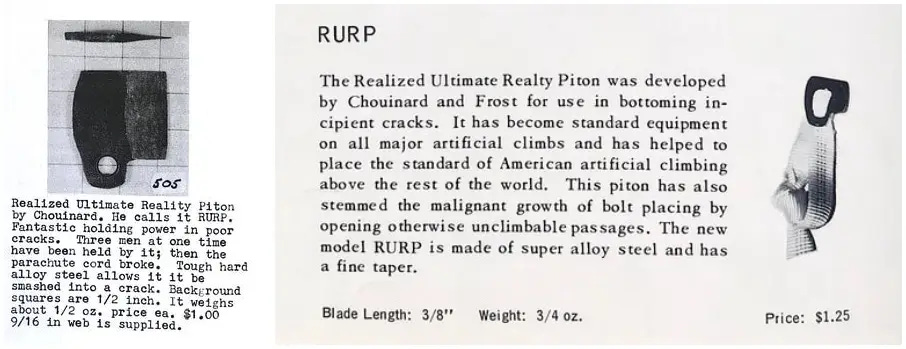

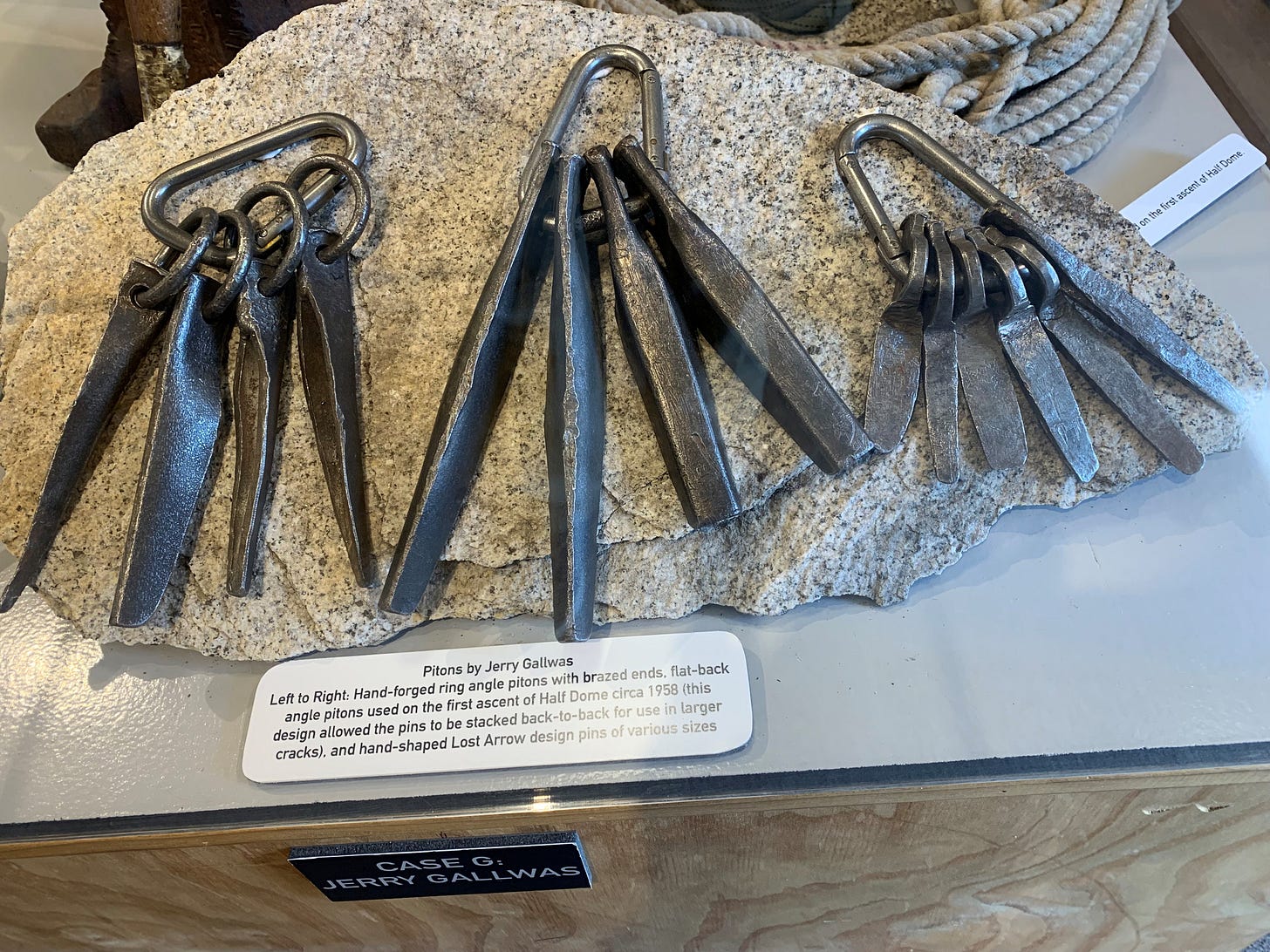

1954: Chuck Wilts shares information on his 4130 Chromoly thin pitons in the Sierra Club Bulletin (and in “Belaying the Leader, an Omnibus on Climbing Safety”, 1956) and soon a number of makers begin making Chromoly pitons, which then becomes the standard for all high strength steel pitons, craftsfolk include Richard Long, Jerry Gallwas, George Rea, Bill Feuerer, and Yvon Chouinard.

1950s USA-an age of piton innovation.

Typical climber’s“Rack”: In the early 1950s, most American piton climbers would have had a few army Gov’t surplus pitons, a selection of “soft-iron” (mild steel) pitons brought over or shipped from Europe, and perhaps a few high-quality hand-made steel pitons from a USA designer and maker. Carabiners would have been a mix of steel and some aluminum. Racks of gear were heavy, and limited in the range of sizes (~3mm to 10mm widths). The time was ripe for another gear evolution.

Designing new gear for the new big wall challenges on the granite and sandstone mountains of the North America led to a productive period of equipment innovation in the USA, with arguably four ‘centers’: California, Colorado, Washington, and the East Coast. This story will be told in two parts, 1920-1940, and 1940-1960s. This page as reference material below, and will be updated with further research and as others contribute. Many thanks to Marty Karabin (MK) and Ashby Robertson (AR), whose images are noted below. Other sources TK.

Chronology 1940s-1950s (draft)

TO BE UPDATED WITH MORE EXAMPLES AND DESIGNS: Bob Owens, George Rea, Jerry Gallwas, Bea Vogel, others…

MORE 50s and 60s To Come: 4130 Chrome-moly steel consolidates as the standard piton material for all USA-made pitons.

Addendum with more information from Richard Long and Jerry Gallwas here.

CMI, Forrest, and SMC also begin making quality hardware in the 1960s (TK).

Slings in 1956: 1” military spec woven nylon webbing

Rock Shoes 1957

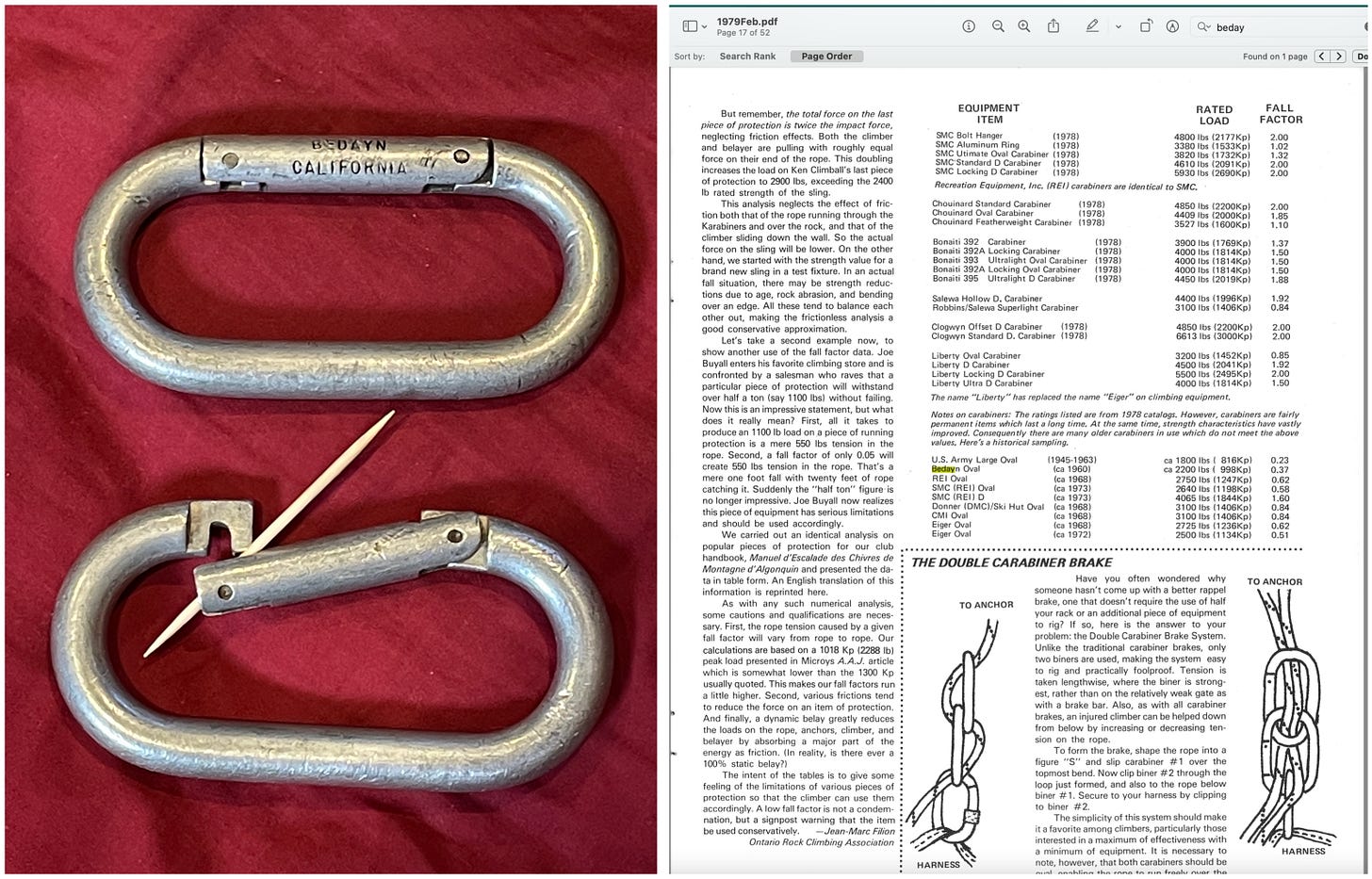

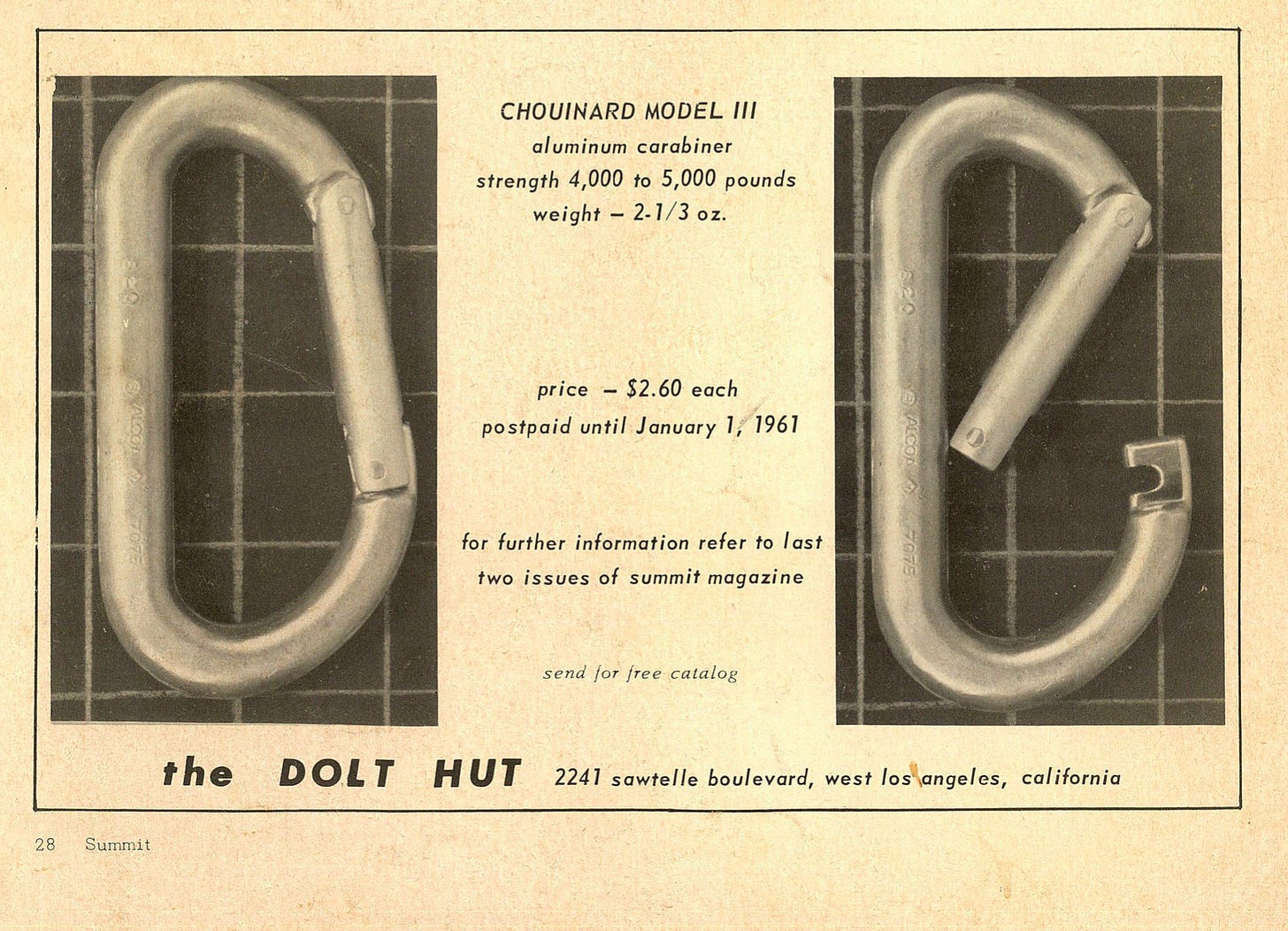

Best Big Wall Carabiner 1940s(?)-1958:

Best Big Wall Carabiners 1958-1961+

Studies/Tests

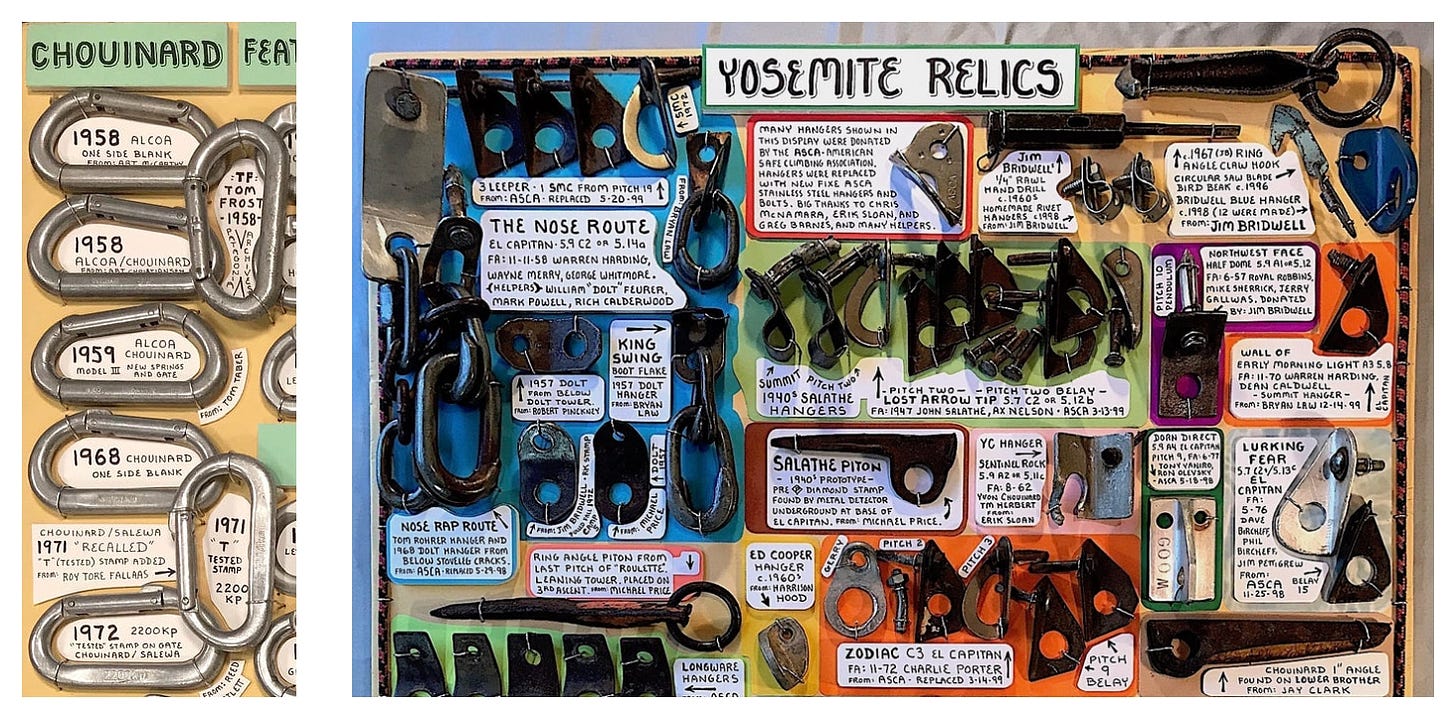

MUSEUM COLLECTIONS

American Alpine Club, Golden, Colorado:

Gary Neptune, Boulder, Colorado:

Marty Karabin, Phoenix, Arizona:

John Middendorf Collection, Hobart Tasmania:

Teasers/notes:

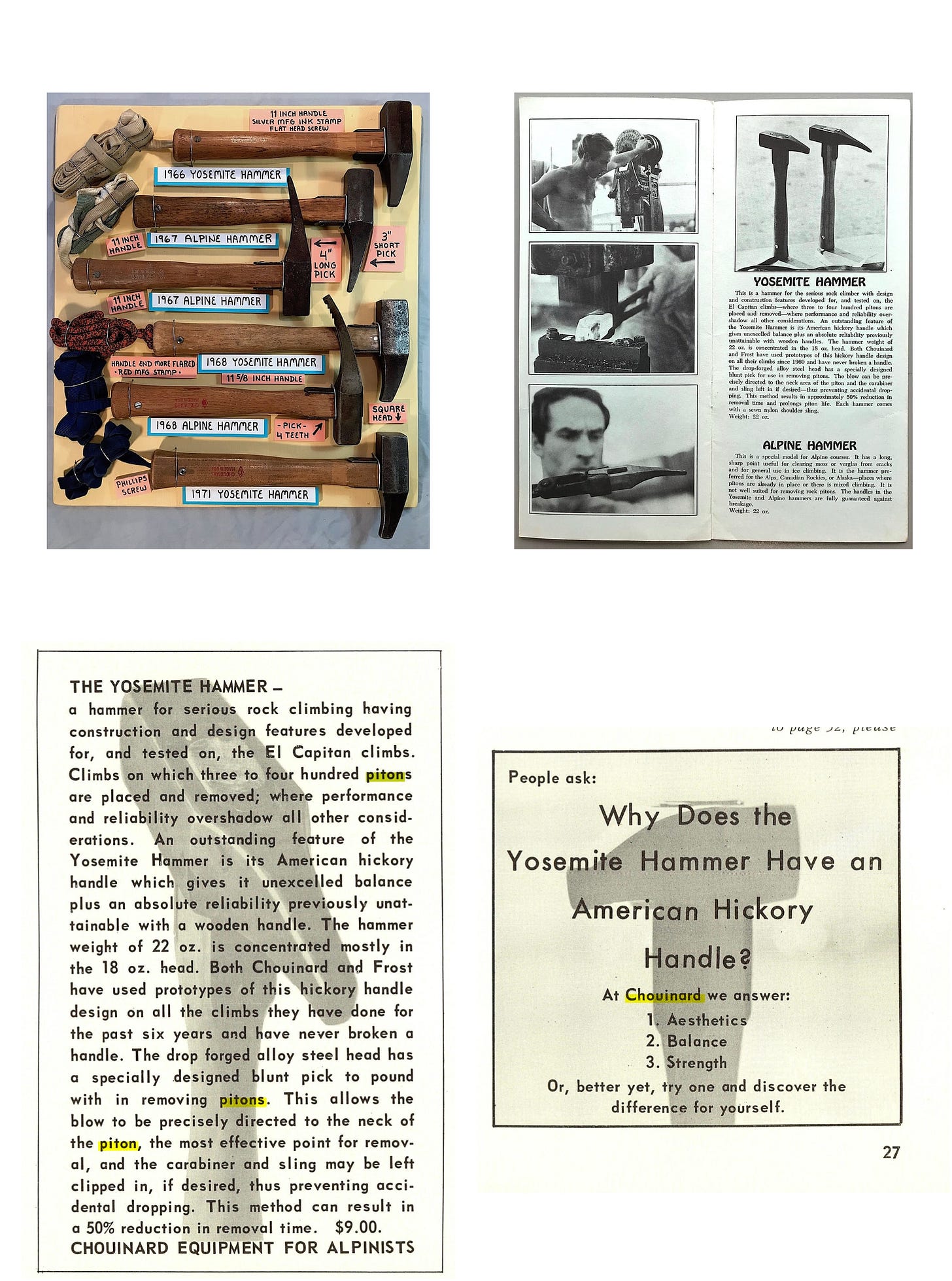

More on A5 hammer development as a study in chromoly production drop forging…

notes from Jeff:

John -

Great article, as always.

One note on piton steels: as you noted, mild-steel pitons conform to cracks, and in areas with very irregular cracks (limestone), this trait has some advantages over harder steel pitons. A hard-steel piton will break and punch through the rock to form a straight channel. It may be stronger when initially placed, but the placement is very susceptible to loosening via freeze/thaw, etc. A softer piton has conformed to the shape of the crack and will retain its holding power (corrosion notwithstanding) for much longer. The metal will have to be straightened out in order for the pin to pull.

Given that a lot of early piton innovation occurred on limestone, which has very irregular crack geometries, and most uses involved relatively low loads, it’s arguable how important it was to use harder steels. In Yosemite, with its extremely uniform cracks, and abundance of wider cracks, hard steel provided a much more universal advantage. You can also see how the destructive (but economical) practice of removing pitons came along with the use of harder steels. For leaving fixed, softer-steel pitons are still the better choice in most instances.

- Jeff

Jeff Achey

Creative Director

Wolverine Publishing

Hi Jeff

I believe a small rack of pitons are still essential for remote big wall climbing. I hear a lot these days of people bringing big power drills to the mountains (ie Skinner/Piana on Proboscis in 1992 along with helicopter access, etc), because I think the art of piton craft and the occasional 1/4” bolt is mostly the domain of a few, and often misunderstood.

So for a remote wall, strong, reusable pitons to minimize impact is better than the current trend of bolting as first choice if not clean.

I am not aligned with the current zeitgeist thinking that bolts are “clean”—In 50-100 years they will all be junk.

So that is my thinking, that hard reusable steel pitons are still an optimal first ascent big wall tool for fast efficient alpine ascents, so I wanted to document their development. I think I covered all the details of mild steel being better in limestone, etc, in my earlier Europe research rambles.

I will probably get into all the ethics, etc in other pieces, this one was just for general timeline to better understand that it was not just Salathe and Chouinard who invented high strength steel pitons in the period.

Thanks for reading, and hope to keep collaborating with you on various eras. Eventually I do want to convert all this research into some sort of readable book, and you would be a top resource to help me with this if I ever got there….

Cheers

_______________

John Middendorf

On 19 Aug 2022, at 6:03 am, Wolverine Publishing <jeff@wolverinepublishing.com> wrote:

I agree on lots of that. I wasn’t really critiquing your article, just noting that soft pitons often work better for fixed protection - possibly replacing bolts in some cases - than hard steel pitons. Maybe the ideal would be an appropriate titanium alloy that was both corrosion proof and somewhat malleable to resist free/thaw loosening.

Jeff Achey

Creative Director

Wolverine Publishing

From: John Middendorf <deuce4@mac.com>

Subject: Re: pitons

Date: 19 August 2022 at 9:50:00 am AEST

To: Wolverine Jeff Achey Publishing <jeff@wolverinepublishing.com>

Cc: Jerry Gallwas <gegallwas@msn.com>

Hi Jeff

Definitely agree with you, especially on your specialty--going fast and light and bold on hard long-day free climbs. I could see taking a few titanium or mild steel ("ok, "soft iron" is probably not going away) for a long mostly free route, where placing an intended fixed pin on lead would be way easier than bolting. But does anyone really climb that onsight style anymore? Seems like everything is practiced now.

My focus of studying the evolution is really about the dreams of youth I never did, because I wasn't good enough or had the time (or money), routes like the huge north alpine big wall of Jannu, or any number of beautiful lines on big no-name faces in the Karakoram and Himalaya (Baffin and Patagonia pretty mature). Jannu has been done with lots of fixed ropes, and there are some amazing routes on the ridges, but the main wall has a line that could conceivably be done alpine style. For routes like that a team would have to go light, but having a rack of a few beaks and Lost Arrows and maybe a baby angle or two would be the go. They'd have to be resuable. Titanium no good as very hard and brittle. That is the beauty of what Chuck WIlts brought to the table, choosing 4130 out of all the choices (though 4130 was becoming a major supply, generally indicated by all the shapes and sizes the raw billet comes, at the time--but there were other high alloy steels to choose from). It really is the best steel for a strong, reusable piton, mostly because of its versatility of heat treatments. Wilts knew the relationship between hardness and toughness, Gerry Cunningham might not have with his first "stubby angles", a great design, but someone snapped one of his pitons with a few sideways blows which indicates way too hard (probably not annealed). Chouinard figured it out pretty fast. I am really hoping to hear from Jerry Gallwas soon. I had some discussions about this with Tom Frost when he would come to stay at my place in San Francisco (during his divorce), but foolish as I was, I was more interested in his experiences on walls far and wide, which has already been well documented. We talked a lot about design, but more about future designs, not past design work, though he clued me in on Ajax Forge, location of hammer and other Chouinard forged stuff, before he got CAMP pitons, a good tidbit, especially as I had also used Ajax Forge for my A5 hammer design two decades later). There are also some lessons to be learned about starting up production for a small time player, something it would be good to see more of, for those interested in innovation. Guys like Mark Blanchard inventing and producing a solo device for a few hundred people seem to be long gone.

Always interesting to watch from the stadium how climbing evolves. Hoping to have a week climbing in Arapiles with my kids next month.

What are you working on now, and when can we see it?

Cheers

cc Jerry

_______________

John Middendorf

portaledge design: bigwalls.net

historical writing: bigwallgear.com

email: deuce4@bigwalls.net