Post-WW2 American Steel Pitons addendum

Mechanical Advantage Series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Continuation of 1950s piton development…

More on steel:

(and new information from those who were there)

Writing online has been a great process. My initial research is often enhanced by contributions from historians around the world, and I am able to update pages with new, relevant evidence in the ongoing story of tool and technique evolution in climbing.

Richard Long, Jerry Gallwas, and Jim Erikson have recently responded with experience and more details of materials and processes, and along with historical American steel manufacturing records, a clearer picture emerges of early USA steel pitons.

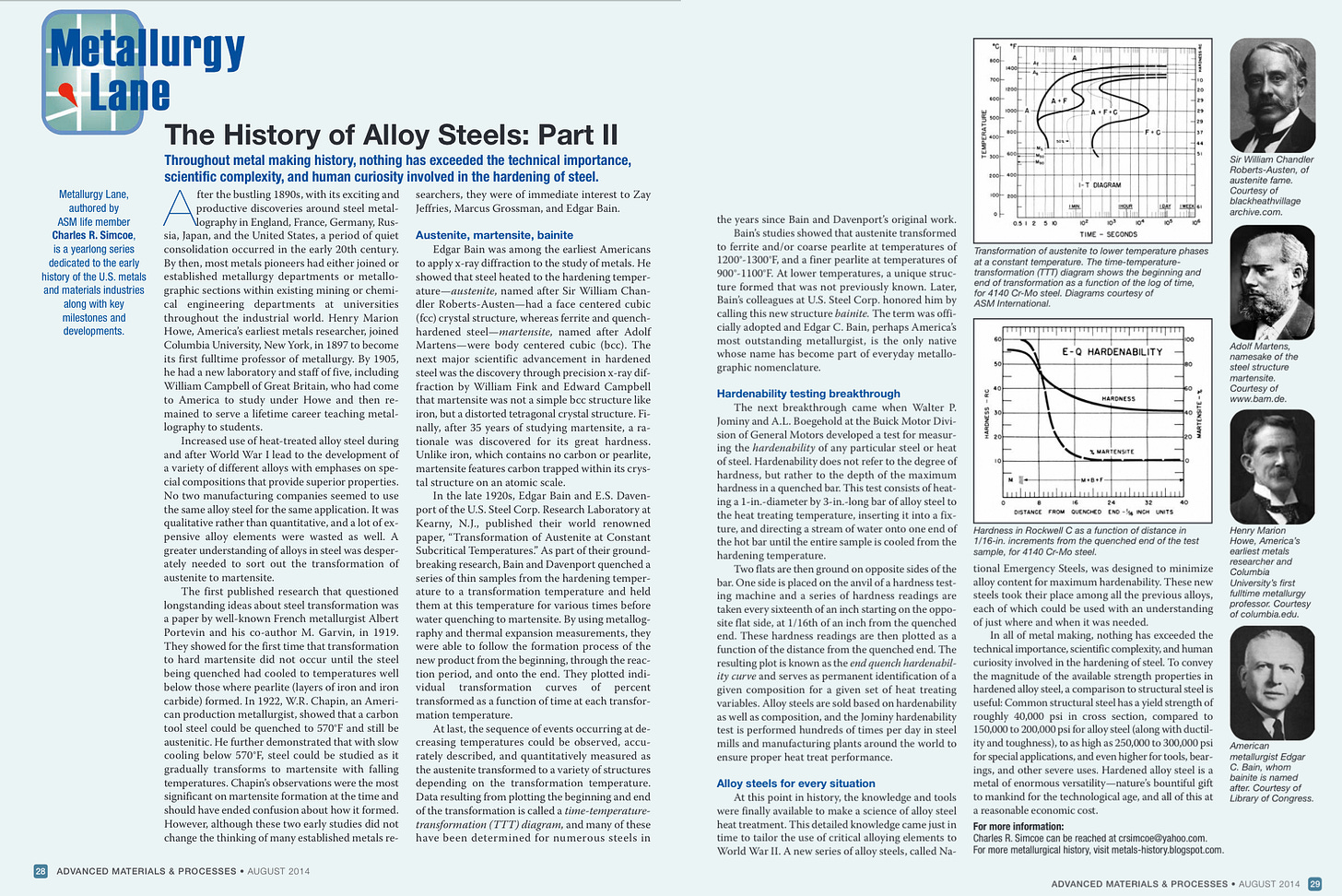

Chuck Wilts is acknowledged as the definitive source of awareness of 4130 steel as a piton material. He also clarified, from the material science engineering perspective, how the heat treatment process was the most critical design feature of making pitons. Chromoly steel (4130) in the 1950s was becoming one of the more common high-strength steel alloys, with very versatile heat treat hardenability for a variety of steel tools. See this post on the A5 Hammer production for a more detailed example of creating a forged 4130 steel part in the 1980s.

By the 1950s, small-scale heat treat shops were a growing industry. In the 1940s, John Salathe probably heat treated his famous Lost Arrow pitons in his shop. Heat treatment involves quenching the piton in oil or water from a high temperature to lock in the martensitic grain structure and results in a very hard and brittle piece of steel. Then the part needs to be tempered in an oven at a very specific temperature and for a very specific time (the developing science w/ 20th-century steel production and use).

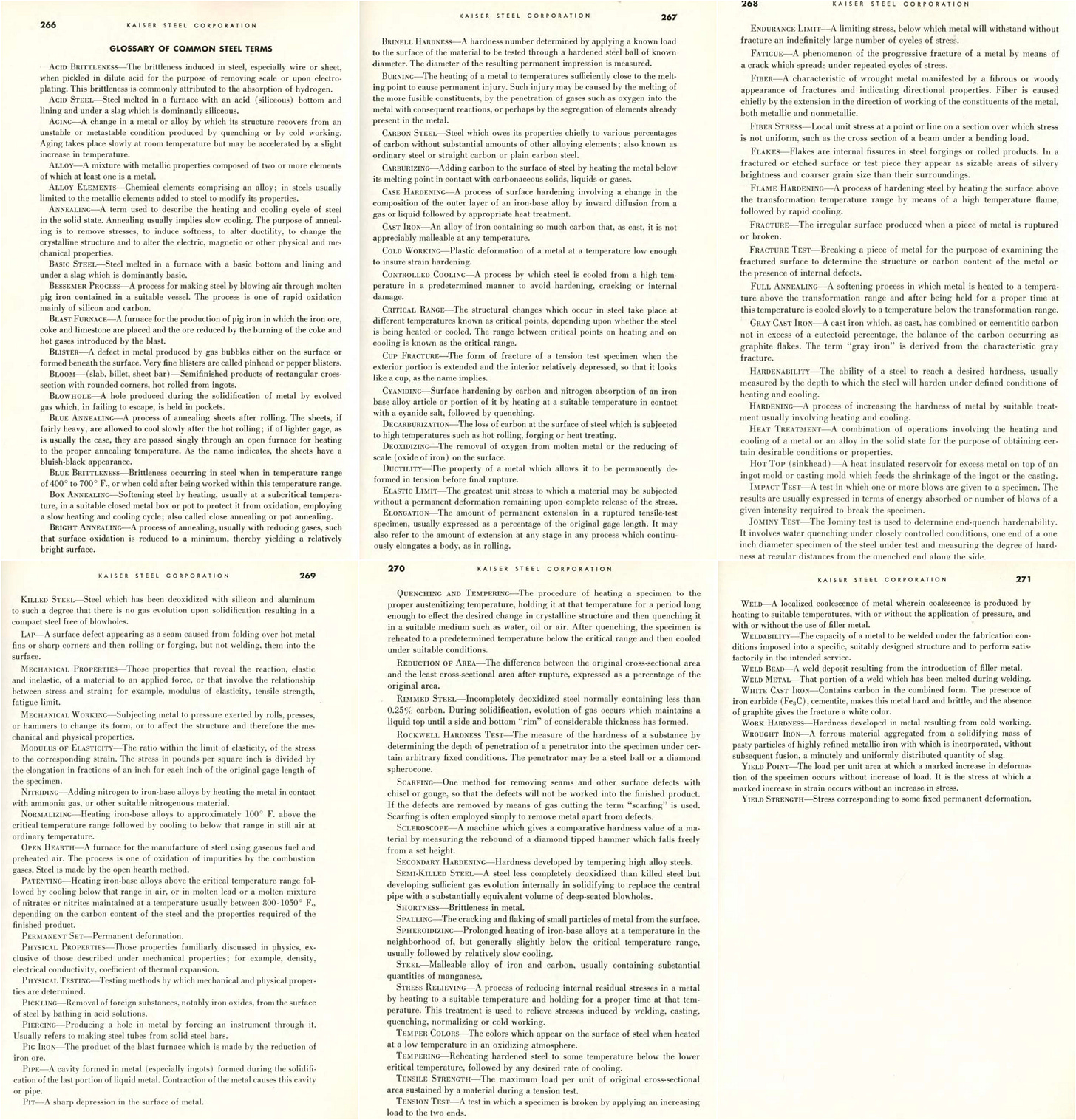

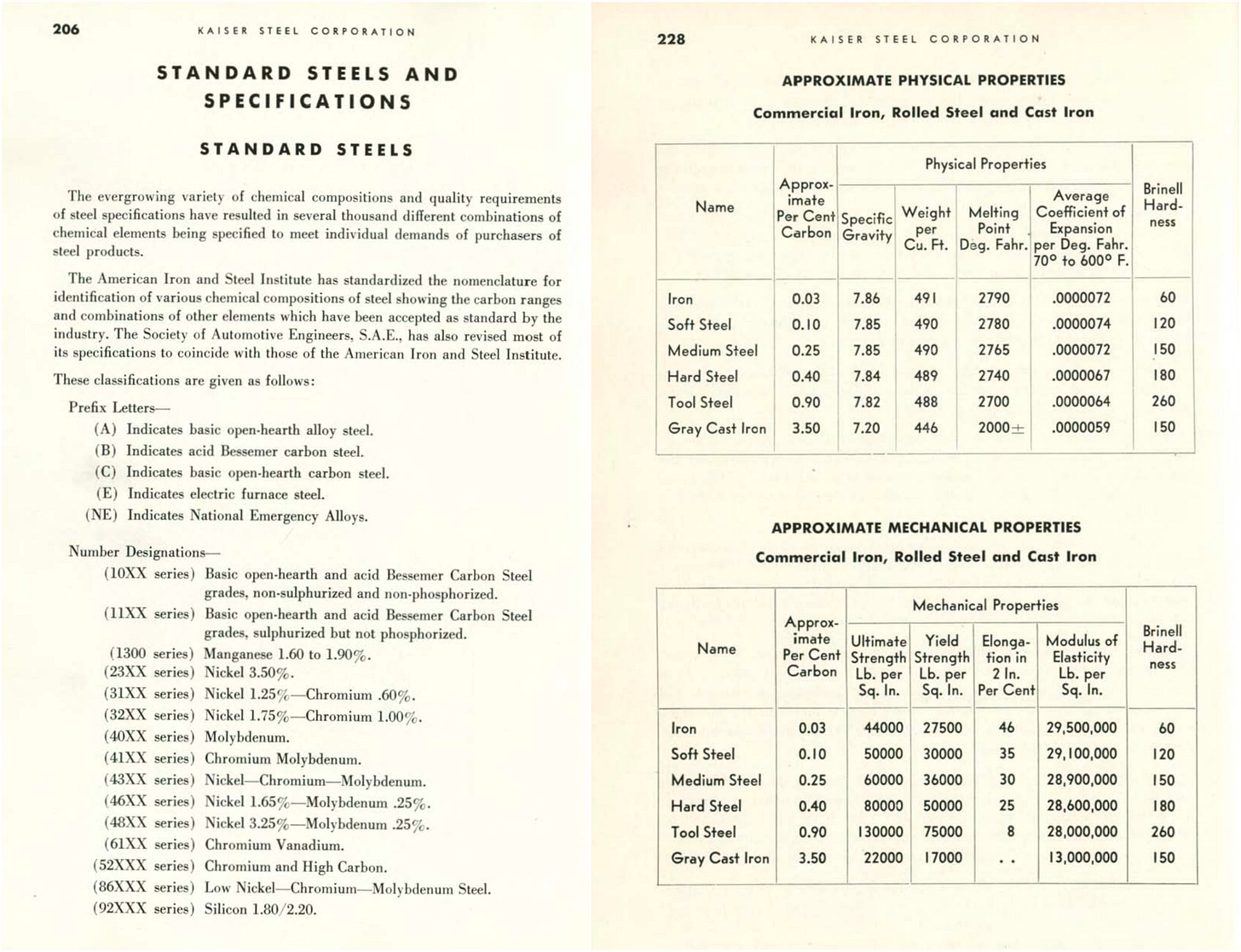

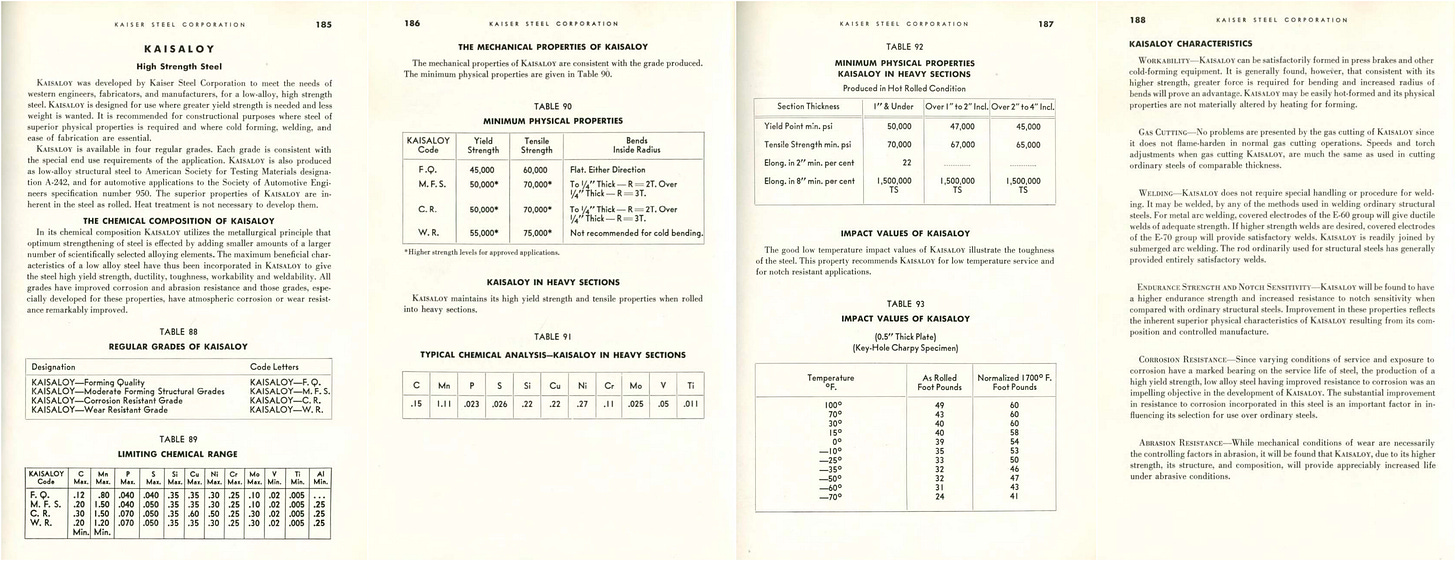

Steel Reference Information, 1953

Steel catalogs like the 1953 Kaiser Steel General Catalog were (and still are, in fact) valuable references for a blacksmith in terms of workability and production of steel parts from billets, plates, sheets, and other semi-finished steel products used as raw material for new tools.

Chromoly Steel

Lots of names: Chrome-Molybdenum, ChroMo, Chromolly, Chrome-moly, take your pick. These 41xx series of steels (4130, 4140, and 4340 are common grades for high-strength pitons and hammers). Today, these alloys are some of the most common high-strength alloys found from most suppliers, but in the 1950s and early 1960s, the major producers did not list a wide range of sizes in these alloys in their catalogs (interesting history of 4130 tubing here). So the original material for a range of medium- and high-strength alloy pitons prior to the 1950s would probably involve a wide range of alloys. But when Chuck Wilts published his research in the Sierra Club Bulletin, 4130 was recognized as the ideal material for climbing pitons, and suppliers found.

Richard Long Recollections 8/29/2022

(See Longware hardware collections in prior post). Of interest to tinkerers!

RL: Longware was initially formed by Larry Lackey and me. After his injury on the Higher Spire, Larry gave up climbing and went on to be a successful “precious metals" hard rock geologist.

Q: Do you recall your material suppliers, and what stock material you were ordering (billets, sheets, etc.).

We purchased 41-30 steel and later 7075 aluminum alloy from, I believe, Bethlehem steel in Oakland CA.

Q: Did you do your own heat treating?

Heat treatment was done commercially. I would wait until I had several hundred pounds of finished material and send in one big batch. After the initial high-temperature treatment, the metal was held for an additional 24 (?) hours at 450 degrees. I had items treated with a phosphate coat as anti-rust and suitable for painting.

Could you tell me a bit more about how you designed/made your angles and your knifeblades?

One of my friends was Dr. Wilkens, MD from LA. and had also read Wilt’s article. He had enough money to hire a machine shop to make a dye punch to Wilts’s specifications. It would punch through 0.093 inch 41-30. I figured out a way to grind the blanks to the proper size. Ideally, they should have been pounded to that size. After several years he lost interest and asked me if I wanted the dies. Dr. Wilkens went on to write several mountain medicine books.

Bethlehem steel used an arc plasma cutter to form the shape for my horizontal pitons. They were cut out of 1/4 or 3/8 inch 41-30 or 86-30 flat sheet metal stock, Then I hired Klockar Forge in San Francisco to drop hammer forge the blade. I punched the eye at home with my personal punch.

All my equipment was made by hand. It was cheap, but worked.

Richard adds: “I really didn’t pay much about who and what was going on or being done. Of Interest, Harding and I would go to the Bay area local practice climbs. I would show him my heavy angle iron attempts and he would show me his latest “stovelegs”. However, when Chuck Wilts knife blade article came out, I learned about 41-30 steel and knew this was the answer! I also knew Chouinard was doing something. In 1957 or 8, I was on the Higher Cathedral buttress, the people who heard the sound named them “bong-bongs”. After the climb, Chouinard and I showed each other what we had been doing. His wide angles went to 2” and mine to 3” and some of mine were relieved. The competition was on. I believe Chouinard would have won regardless. He was totally devoted to climbing! Not afraid to develop something that might work. I had many interests including a wife, two kids, high school teacher and I was trying to get into Med School. To this day Chouinard and I have always remained good friends.”

Thanks Richard!

(more pictures from Richard will be added soon)

Jerry Gallwas

Jerry Gallwas also recognised 4130 as the ideal choice of alloys early on, and was influential in the development of American climbing hardware.

Jerry summarises his contributions below (8/24/2022):

John,

Please pardon the delay in my answer to your E-mail on my exploration into the development of pitons in the 1950s. Sandy and I have been in Scandinavia for the past few weeks, and I have been delinquent in keeping up with E-mail. This is being written as we wing our way over the North Atlantic. I summarized my experience in piton craft in my writeup of the First Ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome. I was inspired to go into rock climbing by the Ansel Adams’ photo of Salathe and Nelson on top of the Lost Arrow that was displayed on the front of Best Studio when I visited Yosemite in 1949. I knew nothing of rock climbing but at the moment I saw the photo I knew I wanted to stand where Salathe was standing and take that photo. A few years later I did just that when Wayne Merry and I made the 5th ascent of the spire. The Ansel Adams’ photo led me to the Sierra Club Journal article by Anton Nelson of their experience and thus the information on heat-treated alloy steel as the intelligent alternative to mild steel which was the basis of all commercial hardware at that time. I lived in San Diego, an aircraft industry city, and so had friends familiar with 4130 Chrome Molly steel and its heat treatment. Chuck Wilts’ experience reinforced my conviction that 4130 was the right choice. Over the years I climbed from 1951 through 1957, I made pitons, horizontal, wafer, and angles for my own use and for friends. Most of the remaining pitons from my climbing days are on display at the Yosemite Climbing Association Museum in Mariposa California. I still have a handful of unused ones but all the hardware and associated gear is in Ken Yager’s possession including the anvil. My grades and draft notice came in the same mail in 1962 and so the climbing student moved on to defend the country. In 1966, I took a 150 fall that ended my climbing years.

Cheers, Jerry

Jim Erickson

When I started climbing in the mid-1970s, there were still a few diehards with hammer and pitons on their racks. But clean free climbing was cooler (I nailed a few pitons when I first started to climb, but only learned pitoncraft when I started climbing El Cap nailing routes in the 1980s). To me, the Colorado climber Jim Erickson was one of the most inspiring climbers of my early era, as he was one of the best on-sight free climbers, known for bold downclimbing incredibly difficult sections to avoid any fall or weighting of the rope, as any aid on the route diminished the spirit of any ground-up future ascent; Jim’s style became my ideal for most of my climbing career.

Prior to the clean climbing revolution in the early 1970s in the USA, Jim’s climbing in the 1960s involved pitons; in terms of piton-protected hard free climbs, Jim’s routes were some of the most feared and difficult. It is quite an art to place a good piton in the middle of 5.11 moves (we call this, “pitoncraft”).

Jim provides valuable information about the European pitons in the later 1960s, and more about Colorado manufacturers. The Europeans were also starting to use more hardenable steel, but it’s probable these were still mild steels with a maximum hardness of ~Brinnel 200. Jim reports the Charlet Moser pitons were best for multiple uses prior to Chomoly.

This page will be updated with new information from time to time.

Appendix