Early engineered rock climbing in the USA (Richard Leonard, 1934) USA part C

USA Adoption of pitons 1920-1939. Mechanical Advantage series (USA partC) by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

The origins of safer rock climbing in America. Please forgive typos with the initial mail-list article—continual updates in the “view in browser” version.

Creative Imagining:

It’s sometimes said, “The best climbers are the ones having the most fun.” But climbing hard routes is often sparse with ‘fun’—most of the fun comes later. Perhaps the best climbers are the ones having the most… realized creative imagination. Creative Imagination is a well-established study of psychology, often awkwardly defined in terms of divergent and analytical thinking, and a vaguely defined “intuitive” process (pure “as-if-from-God” inspiration has never been well defined by psychologists). Artists have it all the time. Pablo Picasso once said, “What one does is what counts, and not what one had the intention of doing.” In other words, creative imagination only exists if realized by the oft-uncharted doing of a thing. In climbing, the ‘doing’ is often packed with suffering, hardship, and flashes of brilliance; later all these moments merge to become the ‘fun’.

America 1930s Climbing

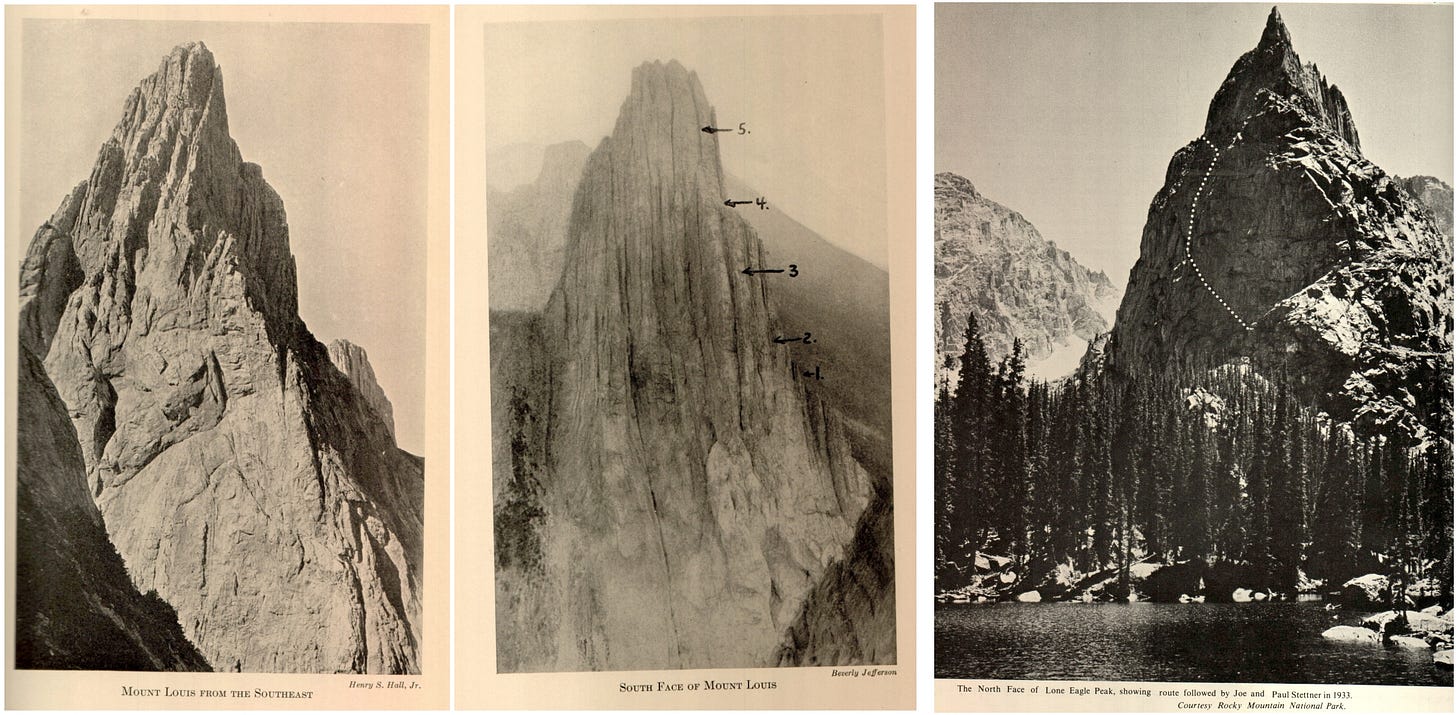

Since the days of Whymper, the initial creative imagining of standing on high summits dwindled in potential in 1930s America, with most significant points of prominence either ascended or noted as only imaginarily climbable. Expeditionary high mountains were still the main focus among the alpine clubs, and tall majestic rock walls such as the Diamond on Long’s Peak were still considered impossible. A modern form of creative imagining expands, involving the increasingly efficient use of tools to ascend “lines” up ever-steeper tall expanses of rock. Three epicenters of creative rock climbing emerged in America as the new tools were incorporated: the East Coast, Colorado, and California, each with their own imaginings of the possible on steep vertical rock, and all contributing prototypes for later imagined and climbed bigwalls.

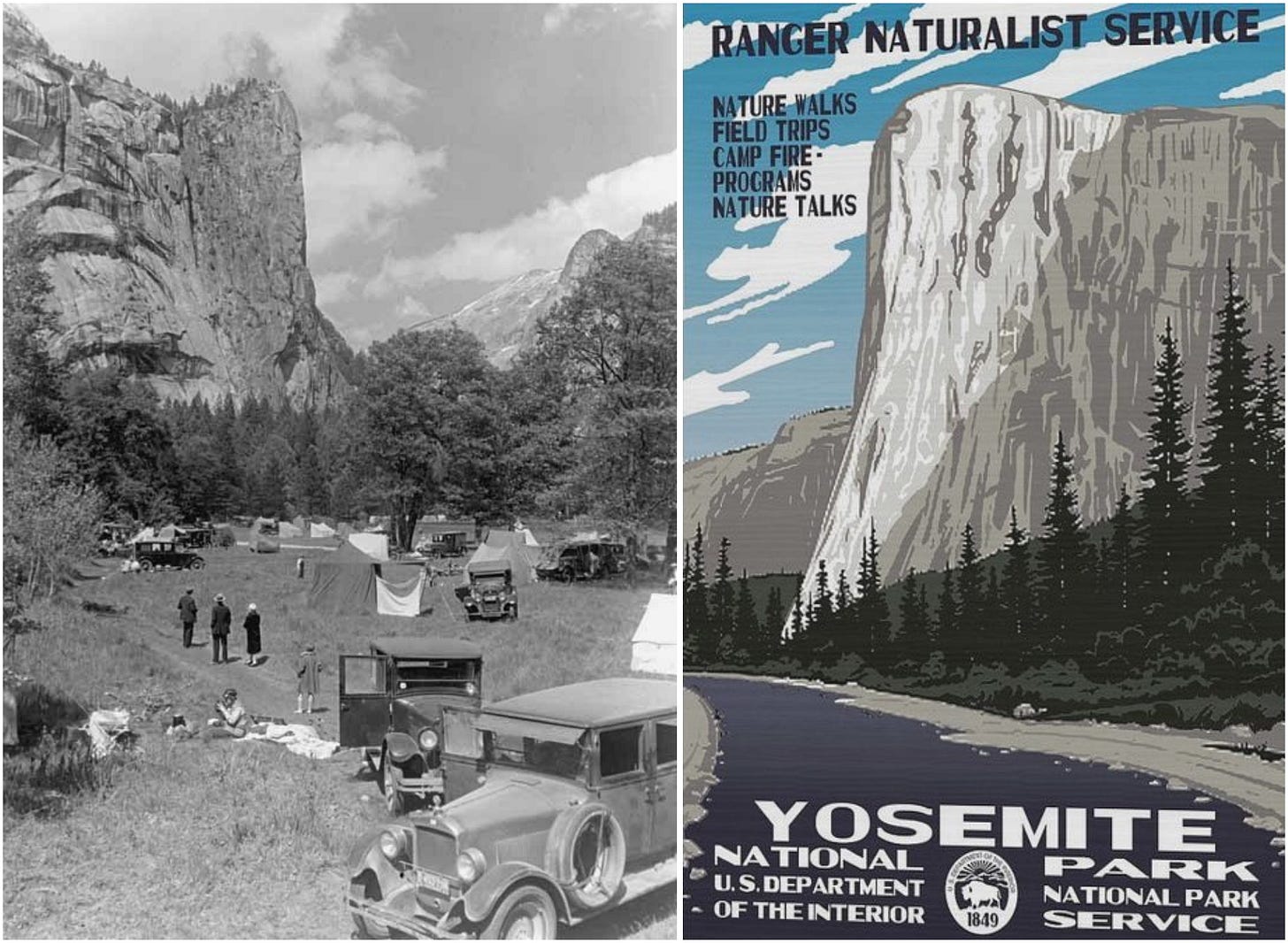

Yosemite, 1934

In climbing’s progression of reducing the risk of falling, nowhere did the transition to efficient piton-protected climbing evolve as fast as in Yosemite, thanks to a young group of climbers from the Cragmont Climbing Club, who first mastered their technical skills on a pile of scattered boulders in the Berkeley hills of California. Led by a young lawyer from Ohio, Richard M. Leonard, the club was to change the game dramatically by introducing a studied engineering approach to the tools of climbing. Founded in March, 1932, the club set out to prove a better way of climbing, first by theory, then by practice, and finally by setting new standards in American climbing.

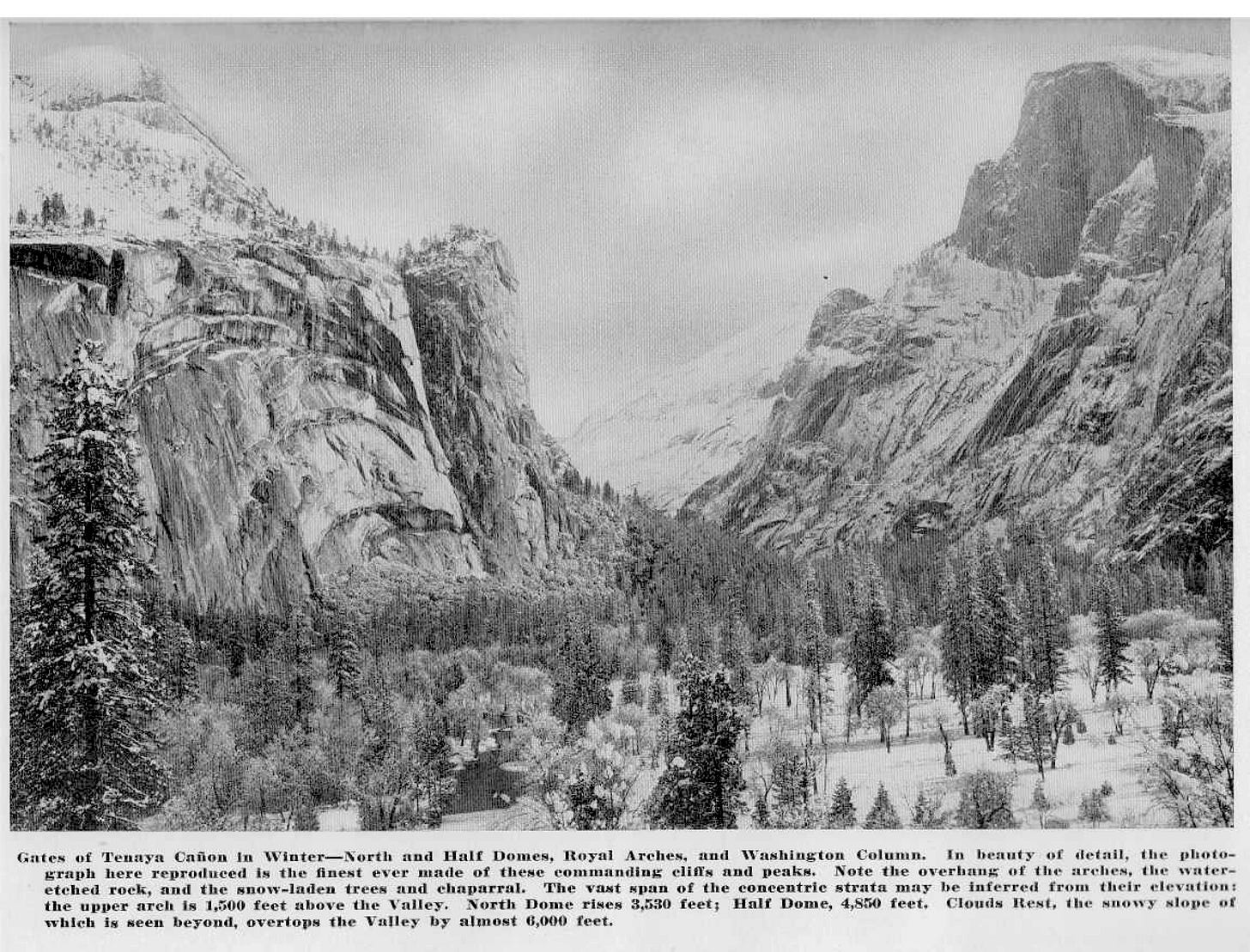

Background on Yosemite Valley rock climbing:

Before its first recorded ascent in 1886, Grizzly Peak had been considered the last ‘unclimbed summit’ in Yosemite. Majestic tall towers of stone in Yosemite Valley—the Cathedral Spires, Split Pinnacle, Pulpit Rock, The Arrowhead and Lost Arrow—were named and admired, but not yet conceived as potential summits for a mountain climber (footnote). In the 1920s in the Sierra Nevada mountains, Norman Clyde became legendary for his hundreds of first ascents of intricate lines, many solo-adventures, on the major peaks. The game then was to climb the mountains from the cardinal directions, and Clyde often discovered new routes to climb, for example, the challenge of the east wall of Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the contiguous USA, was noted as “Whitney from the East.”

Footnote: As Richard Leonard reflected in 1934, many of these towers of rock “had been considered totally impossible. Things like the Cathedral Spires nobody even considered, because they knew you couldn’t climb those.” Also, Grizzly Peak wasn’t really the last peak to be ascended in 1886, as many smaller remote summits were ascended in the High Sierra for decades hence; the peak was named after the Grizzly Bear (North American Brown Bear), once prevalent in that region but extirpated in 1922, when the last one was hunted and shot in the foothills of the Sierras. Elsewhere in 1931, climbs up peaks like the Devil’s Thumb in Alaska were starting to become envisioned, though it was not climbed until 1946 when Fred Beckey, Clifford Schmidtke and Bob Craig ascended via the east ridge; the peaks were noted as the “remarkable granitic spires of the Devil's Paw and the Devil's Thumb. This range may yet be found to contain some of the most difficult climbing peaks in North America.” (AAJ 1931).

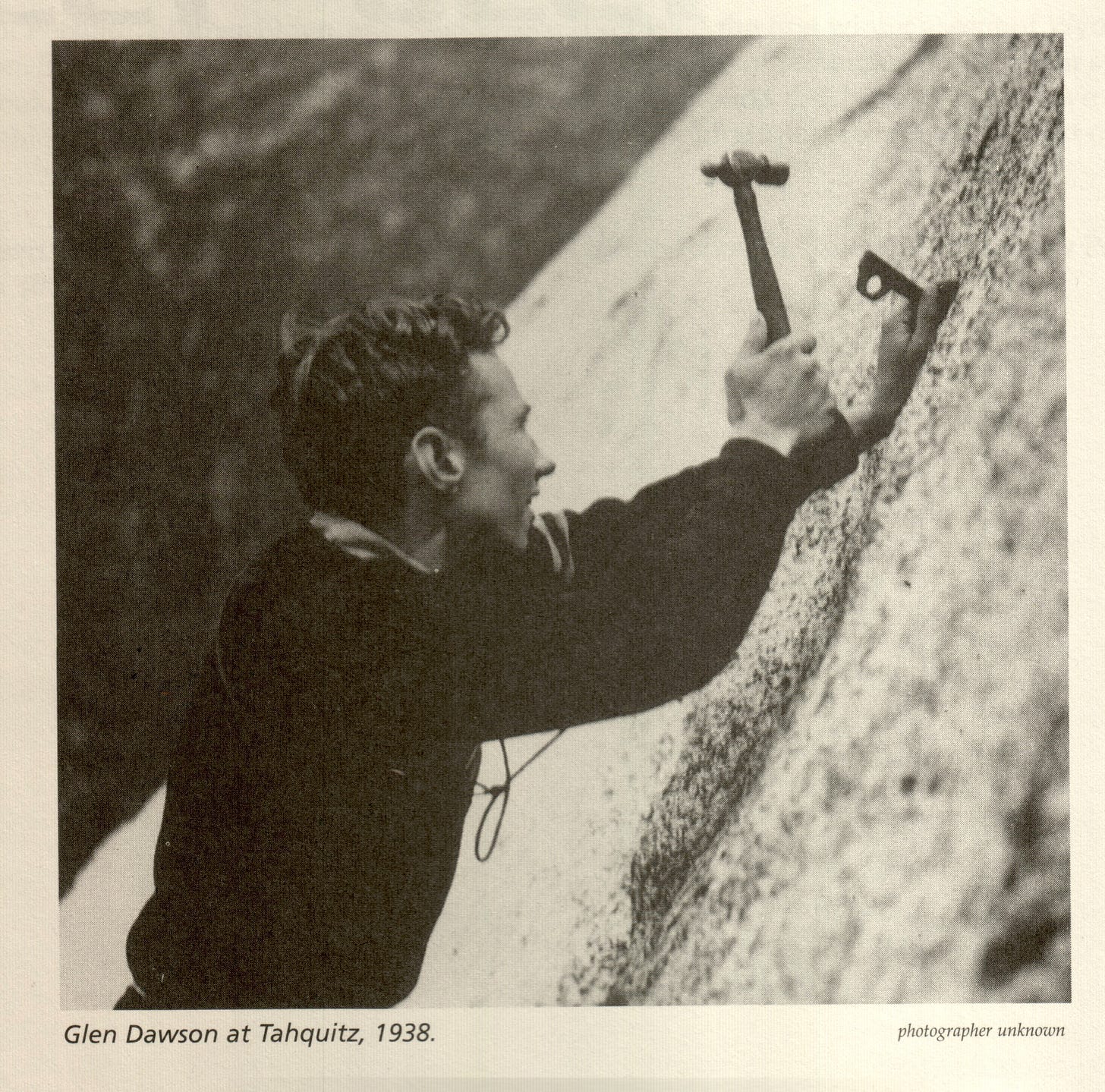

Occasional pitons 1927-1933

By the early 1930s, more routes were made possible with the occasional use of a piton, such as the one that protected the exposed “Fresh Air Traverse” on Whitney from the East, first climbed in 1931 by Clyde, Jules Eichorn, Glen Dawson and visiting East Coast climber Robert Underhill, who shared his knowledge of the European climbing systems of climbing with artificial anchors. The ascent was by no means the hardest rock climb in the Sierras but effectively gave a green light to some of the younger members of the Sierra Club to begin using the “specialized technique” that was enabling a whole new genre of wild climbs in America. In the early 1930s, pitons had been useful on other climbs in the Sierras, as well as for ‘Rope-Down Routes’ over peaks and passes between sub-ranges in the Sierra Nevada (footnote).

footnote: Rappel routes were then known as ‘rope-down routes’. For example, (SCB 1937): Rope-Down Routes. Fourth to fifth class; 200-foot reserve rope required. By the use of many pitons nearly any route is probably possible. It is well, however, to mention certain routes that have actually been used. On July 25, I934, Glen Dawson and Jack Riegelhuth reached Slide Canyon from the NW. arête of the West Tooth near the junction with the Sawblade by a series of four rope-downs involving the use of one piton. At the same time Doris F. Leonard and Richard M. Leonard roped down from the West Tooth toward the Middle Tooth by Route I and thence by three more rope-downs along the SE. buttress to Slide Canyon. The last rope-down, from a piton on a ledge, was 105 feet, most of it over-hanging. On July 7, 1934, Kenneth May and Howard Twining worked out a successful route roping down from the Middle Tooth to Slide Canyon by the great SE. chimney from the East Notch. On September 7, 1936, Carl Jensen, Bestor Robinson and Richard M. Leonard roped down from the Middle Tooth to the N. base by roping off from the lower end of the chimney on the NW. face the upper part of which forms a portion of Route 3. About half of the last rope-down is overhanging. On September 8, 1936, John Poindexter and Don Woods roped down the N. face of the East Tooth from the East Notch. The route is very severe, involving the use of pitons and slings to sit in as one of the intermediate stances. The route involves considerable uncertainty and is not recommended. In the 1954 A Climber’s Guide to the High Sierra (ed. Hervey Voge), these same routes are upgraded to Class 5 to 6 and noted as “Rappel Routes,’ the same term we use today. For more on evidence of wider spread piton use in North America beginning around 1927, see these posts on the Colorado and East Coast climbers. By 1933, the 1932 American Alpine Journal feature on the new tools by Max Strumia was beginning to bore fruit with adherents adopting the new tools.

Snapshot 1933—elsewhere in this period, and information flow

In 1933, American climbers were using pitons more widely but had not yet caught on to all the techniques that had evolved for three decades since the early days of Tita Piaz in Europe, but the art was changing fast in North America. The Europeans by this time were testing the extreme limits of pitons on many of the bigwalls in the High Alps and the Dolomites, from the alpine achievement using a lightweight kit of pitons, carabiners, and slings on the north wall of the Matterhorn in 1931, to the heavily-equipped feats of vertical endurance such as the direct route on Cima Grande in 1933.

In short, in Europe by 1933, piton-protected climbing had developed into a fine art with broad disciplines and evolved specialized tools, with clear concise instructional texts widely available. Along with European-made equipment brought back from climbers frequenting the Alps (and increasingly shipped from catalog suppliers), many of these texts would have also been circulating among American climbers, in addition to tools and technique articles appearing more frequently in the American and Canadian journals. The information was all there, but in the period between 1927-1933, North Americans were deliberating their own appropriate adaptation of the new tools.

In terms of technical expertise by 1933, routes in Colorado, Wyoming, and Canada involved more advanced use of alpine pitons than on the coasts of North America, with more technical rock routes in high alpine ranges like the San Juans; difficult testpieces like Lizard Head Peak were increasing in popularity. Perhaps due to the cowboy heritage of the Rockies (consider the many names for slings: cinch, lash rope, tie-down, short-rope, etc.), and the nature of the climbing, the Colorado climbers were more adept at incorporating slings as part of the running belay on pitches with multiple points of protection, something that appears to have eluded the Californians, and probably also the East Coast climbers, until the later-1930s.

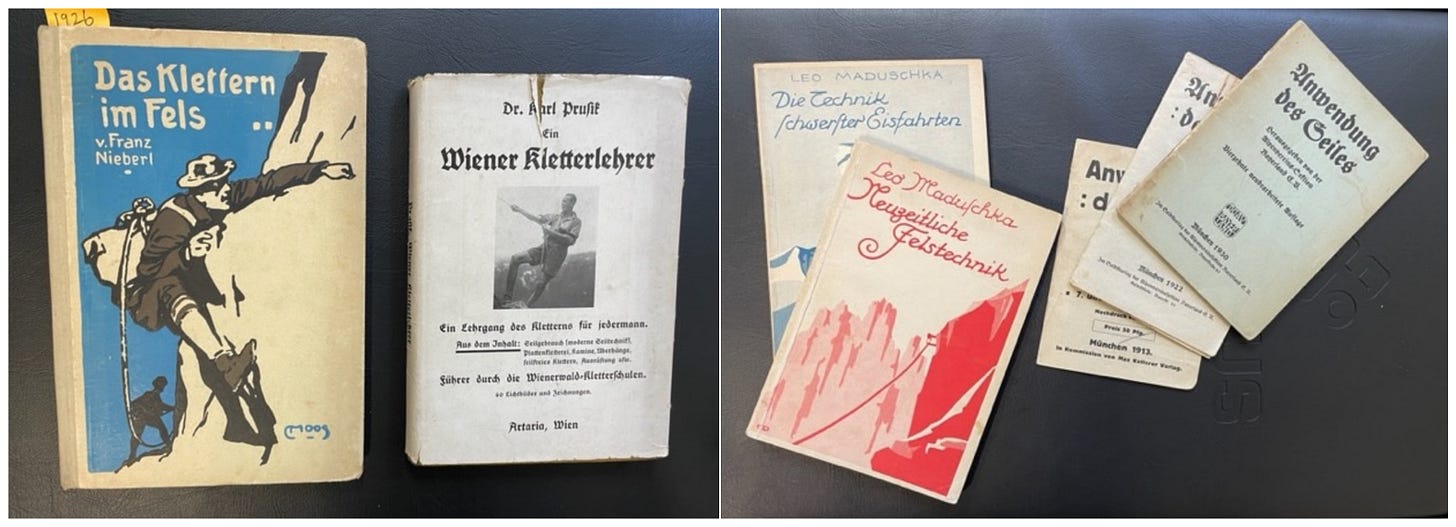

Footnote: Though Franz Nieberl’s “Das Klettern im Fels” series (first published 1911, updated every few years to 1966) would have been one of the more popular climbing introduction books in Eastern Europe, with tens of thousands of books printed, the Karl Prusik (1929) and Leo Maduschka (1932) texts seem to be more referenced in early English (and French) journals. Richard Leonard reports in Belaying the Leader (1946) that by 1934, the Leo Maduschka 1931 treatise had been translated into several languages, describing in detail with profuse illustrations, ‘the new piton technique of Europe.’ In terms of climbing experience, Fritz Weissner, who in 1925 climbed some of the world’s technically hardest “Grade VI” bigwall routes (SE wall Fleischbank with Roland Rossi and Fritz Weissner—noted by Rudatis as using the “extensive use of nails”— and La Furchetta with Emil Solleder), once he moved to America in 1929, he became a proponent of pitons exclusively for security, and not for direct aid. Weissner was also a masterful gear-protected free climber with his experience in the Elbsandsteingebirge, and had also climbed to 23,000’ on Nanga Parbat in 1932; he later advocated for pitons for the K2 attempts in the later 1930s, so his views on artificial aid and the appropriate use of pitons within the American community were also influential. More on Weissner later. Interestingly, Richard Leonard even in the 1970’s believed the horizontal and vertical piton designs we use today were invented by ‘a German by the name of Dülfer a few years before’ 1932, even though Dülfer had died in 1915. The American version of the ‘Dülfersitz’ as a body rappel method was becoming standard around this time in America.

Style and Ethics evolve in North America

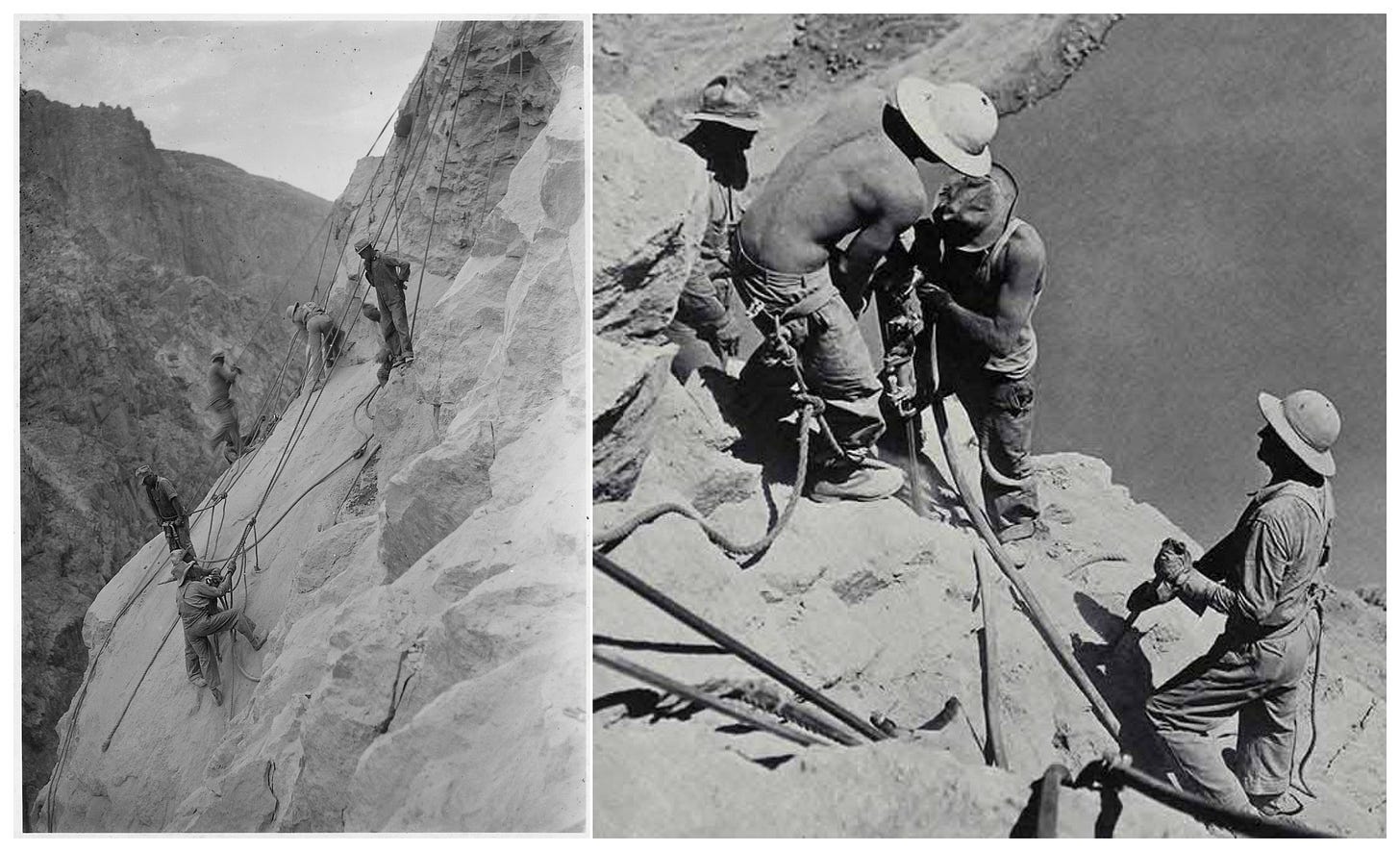

Just as the debate over appropriate climbing tools had raged in the British journals in the prior decades, around this time, we see more writings in American journals either defending or attacking the use of hardware on rock climbs. Increasingly few argued against using pitons for security (as a belay), while the leading purists oft reiterated the timeless argument that with enough technology, anything could be ascended, as this period was also a golden era of professional rock engineers such as the ‘high-scalers’ who famously built the Hoover Dam at high risk (over 96 people died in its construction). Richard Leonard wrote in 1934: “George D. Abraham, one of the leaders of British climbers, said that it is not sporting to use pitons though it’s all right for climbers who are professional who are doing it for pay; but an amateur climber should do it for sport and not protect himself.”

So unlike in Europe, where increasing reliance on tools in the mountains had undergone a steady progression since the 1900s leading to the heavy aid routes that were all the rage in the Eastern Alps in the early 1930s, the Americans were initially more conservative in adopting the pure aid techniques that would later enable great climbs such as El Capitan from the southeast and southwest. Using pitons as hand- or foot-holds was still highly frowned upon, and the normal progression would be to first attempt an objective without hardware, and if deemed necessary, a minimal set of tools would be collected and applied on the next attempt. At the same time, imaginative climbers were seeing new potential and possibilities of systematically using the piton, rope, and carabiner system as a way to minimize risk on complex steep lines on the stone on the challenges in America, using a combination of free and aid techniques (footnote).

Footnote: from here on, ‘Aid’ refers to using artificial tools as a means to directly gain upward ascent, in contrast to only using hands, feet, and other body parts as connections to the rock while ascending (‘Free’). Prior to the 1930s, ‘Artificial’ (and thus ‘aid’) referred to any use of pitons in the mountains, even if only used for ‘security’ (the German word for ‘security’ can also be translated as ‘insurance’, i.e. insurance in case of a fall).

ROPE UNDERSTANDINGS 1933

Increased reliance on fixed hardware in the rope system added a new dimension to the engineering aspects of climbing, yet it was not until the 1930s that important properties of ropes were better understood by many climbers; namely, the elongation and energy-absorption properties. Articles reviewing ropes focused on the external aspects, such as suppleness and handling characteristics when wet, with a minimum breaking strength recommendations of at least 750kg. This usually translated to a well-made manila or hemp rope, with quality source fibers and yarns, twisted lay, about 12mm in diameter. A typical kit for rock climbs included a 100-foot (30m) 12mm rope, and a 200-foot (60m) 10mm rope for rappels. As seen from the chart from a 1934 French instructional below, silk ropes were also available, though at much higher cost, but if not well made would not be significantly stronger than the less expensive manila or hemp ropes (for more details of rope fibres, yarns, and method of manufacture, see this post).

Footnote: The nomenclature for the natural source fibers was muddled in this period. Confusion over the fiber material abounded—often we see terms like “Manila Hemp” and “Sisal Hemp”, even though the hemp fiber was a different plant altogether from manila or sisal. Also, one Italian Hemp rope was not always the same as another. Italian Hemp was an imported product in its raw material form, and the strength and quality of rope highly depended on first the yarn-making, and then the rope-making production process, with many cheaply made ropes on offer—hence the minimum strength requirement from a reputable supplier. Debates on the benefits of a “right-handed” or “left-handed” lay also entertained equipment aficionados.

Dwight Lavender in Colorado promoted a woven linen rope made for yachting, a well-made rope from the Plymouth Cordage Company, which had test strengths that exceeded hemp and manila, and likely had improved elongation properties due to its woven construction, but linen flax as a rope material was not as robust as hemp or manila with heavy use and is more susceptible to UV damage; woven ropes in general, though better handling, did not hold up to the rigors of climbing as well as 3-ply twisted ropes, and were generally not as strong.

Footnote: The Pymouth Cordage Company was the main supplier of climbing ropes in the USA from the 1930s-1970s, including the famous 3-ply nylon Goldline—see images and notes in the appendix.

The leader must not fall

Every climber understood, in theory, the huge shock loads of a falling climber, thanks to many stories within the climbing community of a climber’s rope snapping (or getting cut over an edge) during a dynamic fall. But in 1933, there was very little understanding of the rope’s ability to absorb some of the energy of a fall, and many reviewers considered a rope’s ‘sponginess’ a detractor, even though it generally meant less impact load on the belayer and the climber in the case of a fall. The “indirect belay” coined by Geoffrey Winthrop Young in Mountain Craft simply recommended using the human body and grip to resist the forces of the fall rather than quickly tying the rope off to a fixed anchor, though in some cases the latter was considered appropriate if the leader was deemed reckless and could pull the whole party from the cliff, in which case a ‘direct belay’ (a fixed anchor—perhaps the rope wrapped around a natural rock bollard) resulting in a broken rope and a dead leader was preferable to the whole party going down. That was about the extent of the knowledge of dissipating the energy of a shock load for most climbers and climbing instructional book authors in 1933.

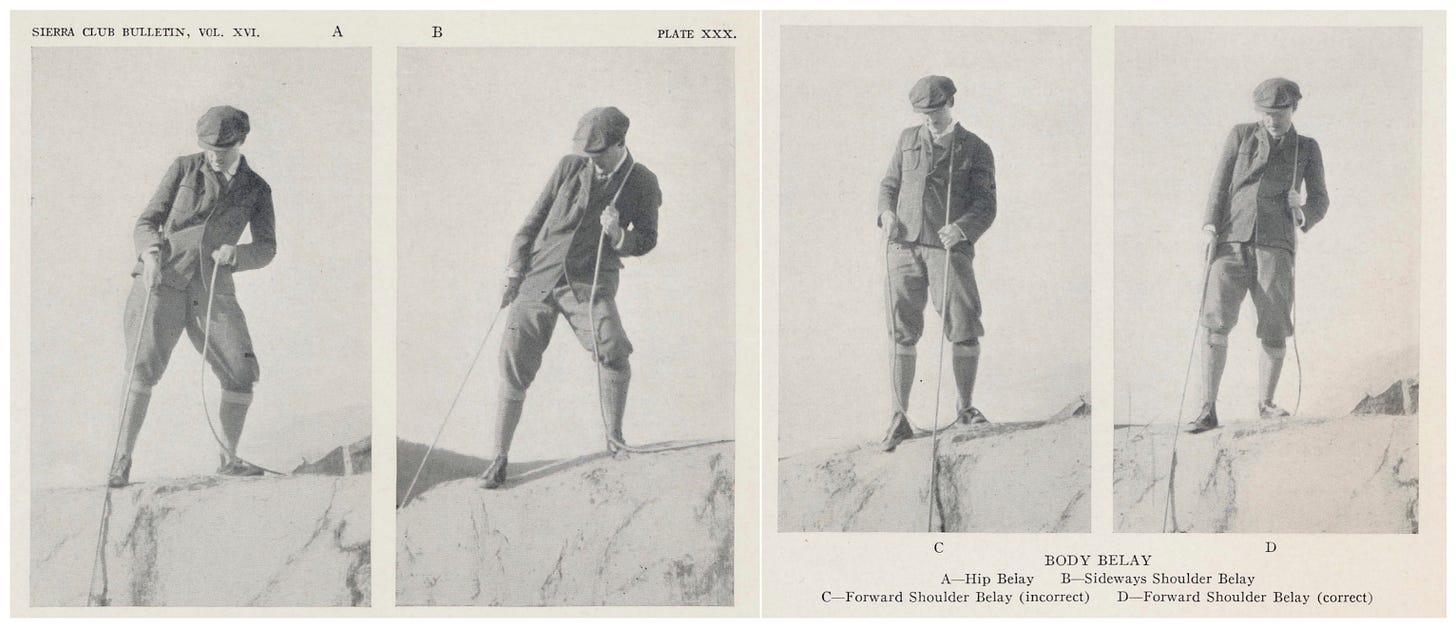

The recommended high-center-of-gravity shoulder and high-hip belay methods would be difficult to catch a long fall without getting pulled uncontrollably from a perch—the main reason piton anchors became acceptable with climbers risking longer falls, even though the solid anchor increased the chances of rope breakage. Some climbers, such as Miriam O’Brien, did understand that some slippage of the rope was desired when catching a fall, but how to best control slippage (and how much) is not an easy skill to master, and no specific methods are offered in the period’s instructional literature. So with all these factors, the climbing community simply reiterated, as if a mantra, “the leader must not fall.” That is, until Richard Leonard came along in 1933.

Enter Richard Leonard (1908-1993)

In 1933, the Sierra Club’s conservative “board of directors did not approve of rock climbing because they thought it was dangerous.” (Richard M. Leonard, Mountaineer, Lawyer, Environmentalist, Volume I, 1975). And it was. Without a surefire way to keep people safe in case of a fall, leading anything more than about ten feet above an anchor was essentially soloing, with the vague knowledge that someone below might catch a long fall, but at worst they won’t also plummet to the deck if anchored securely into a piton.

Leonard quickly realized the standard methods of belaying were more theoretical than practical, suitable only for short falls—perhaps a couple of meters at best. For every doubling of fall length, the energy is squared; in other words, a ten-foot fall would result in a quadrupling of forces compared to a five-foot fall. Leonard reflects on the 1933 situation:

“The European philosophy was that nobody could hold the fall of a leader. To put it another way, if you are climbing a mountain and you have an experienced person who leads the climb, he has a rope to the second man and the third man. Even if they do not have experience, the second and third are protected. But if the first man, the leader, should fall, say, twenty feet, he would fall twenty feet down to where the second climber was and then another twenty feet below him. If the second climber were on a ledge, that would be forty feet before anything could be done about it. To my logical, legal mind that did not seem sensible because it meant that if that one person fell, all three would be killed.” (ibid, Volume 1, 1975).

And indeed, both in Europe and in America in this era, a forty-foot (12m) fall on steep rock in the mountains often resulted in tragedy, with accident reports in the international journals full of morbid tales of double falls, snapping of pitons, and rope failure on big mountain walls.

Footnote: For example, the tragic death of Toni Schmid in 1932, whose belayer could not catch his fall, and they both plummeted down the face of the Grosse Wiesbachhorn (his partner, Ernst Krebs, survived but was badly injured). The American Alpine Journal noted, “The summer of 1931 was a most disastrous one for climbing.” Most deaths were weather-related but long falls were also often to blame. The AAJ article also noted the death of a solo climber in Zion (Don Orcutt on Cathedral Mountain, which did get a lot of press in the general news, as he had just made an early successful ascent of the Great White Throne), and concludes, “Nevertheless, as time goes on, the tragic losses of mountaineering appear to be getting relatively insignificant. Last season, the press reported over two score deaths in football and twenty killed and one hundred and one wounded during the hunting season in New York State alone.” Regarding piton attitudes among Sierra Club members, no articles or information about the safe usage of the new tools appear in the Sierra Club Bulletin until 1934 (unlike the American Alpine Club which had been describing piton-protected climbs since 1930, and the AMC since 1928).

The creative imagining of Leonard

Leonard “felt very sincerely that no one should ever have to risk his life climbing.” and notes, “Some of the German climbers, in their publications, had stated that it was perfectly proper to risk life for a major climb. We did not think so.” (Volume 1, 1975). His early experience on difficult High Sierra routes helped him envision the next step in American climbing; namely, the extensive top rope practice of climbs “beyond the present ability of the climber” to safely gain confidence in the limits of athletic ability, and “the systematic practice of falls and belays.” Compare Leonard’s ideas to the contemporaneous wisdom of only climbing within your ability, and that ‘the leader must not fall’.

And so in 1933, at age 25, Leonard and his friends organized the Cragmont Climbing Club to begin the systematic practice of ‘upper belay’ climbing (now called top-roping) in the crags around Berkeley, where he had recently completed a law degree at the University of California in 1932 and was beginning his law practice in the San Francisco Bay Area, later becoming one of the greatest champions of the preservation of America’s great wild lands, leading a long series of American environmentalists that understood the importance of the legal process in accomplishing an environmental objective.

Among Leonard’s early partners for the freefalls were the older Bestor Robinson (35 years old), and the younger and athletic Jules Eichorn (21 years old). [author note: I like to include their ages because many of these climbers had long careers, and were still climbing in the 1970s, so never seemed young to our young eyes].

Improving on the idea of an “indirect belay”, the free-fallers theorized that there would be an optimal amount of slippage, based on the length of the fall, so the fall could come to a halt with precise control, and most importantly that even for the longest falls, with a loading force never exceeding the strength of the rope. The technique was combined with more secure body belay methods (under the belayer’s center of gravity, using their mass to begin the deceleration). They also understood the engineering principle of extending the time to absorb the energy of the fall, and that the additional time translated into adding to the falling distance. And that the only way to prove this, and develop new techniques, was to become part of a human experiment.

The early ‘systematic practice of falls and belays’, documented in Leonard’s article “Values to be Derived from Local Rock Climbing” (June, 1934, Sierra Club Bulletin), Leonard and his cohorts extended their safety zone to ten-foot free falls, with a sitting hip belay. By October of 1934, they were achieving 18’-20’ falls, which would have been unprecedentedly intentional falling on the low-stretch natural fibre ropes of the day (footnote).

footnote: Tests with fixed anchors and body-weight sandbags, the same ropes would break during a six-foot fall (FF=1). Climbers in the Elbsandsteingebirge were also testing the limits of rope falls during this time on routes with solid artificial anchors. It was also about the limit of impact force the human body could withstand without damage, so simply having stronger ropes was not the answer. At some point, I hope to relate the rope jumping stories and pioneering with longer jumps on the Parrotts Ferry Bridge and the jump spot on El Cap in the 1980s, as we also had a learning curve in greater magnitudes of impact forces (coincidentally, our ratio was calculated to be 1/3 as well—tc).

Bigger Whippers

As Leonard and his fellow free fallers perfected the technique, the rule of thumb of the amount of rope to let slide around your body/hand frictional system, with a graduated braking force, became a ratio of between 1/3 and 2/3 the length of the freefall, depending on fall factor (footnote). So, a ‘20-foot fall’ would involve freefall for 20 feet, and perhaps another 10 feet of deceleration, for a 30-foot ride total. For long pitches, plenty of rope was saved for the potentially required long deceleration, so with a 120’ rope, a long rope in those days (36m), meant that the maximum length of a safe pitch could not exceed 80-feet, in case a 40-foot deceleration would be required.

Arnold Wexler later developed a complete mathematical engineering proof of the new ideas, which became known as the ‘dynamic belay’, an improved and quantified belay method that fulfilled the technological need to do the hardest climbs with a minimum of risk, in the last decade prior to nylon climbing ropes.

Leonard writes, “These experiments clearly show the fallacy of Young's predictions that pitons could never protect the leader, but were merely treacherous moral support. For our falls are equivalent to a clear fall on an overhang 10 feet above the leader's highest piton, We feel certain that we can hold falls considerably greater than these, and anyway one can usually place a piton at least every 10 feet of altitude on a pitch.”

FOOTNOTE (tech stuff): Fall factor (FF) then only known as H/L—the freefall distance divided by total length of the rope between the belayer and the climber. As Arnold Wexler later showed mathematically, in theory and in tests, only a fall factor 0.25 could be held with a static belay (or a poorly performed ‘indirect belay’). In Arnold Wexler’s excellent engineering and mathematical analysis, published in the 1950 AAJ as “The Theory of Belaying” quantified the fall factor and calculated the ideal braking force and distances of deceleration. Initially, the recommendation was to let about the same amount of rope out as the length of the fall, but Wexler (who called it the ‘resilient belay’ in contrast to a static belay) later did a complete mathematical analysis and determined that with 4 times the climber’s weight, i.e. about 600lbs frictional body belay sliding methods, with between and 1/3 H and 2/3H required for deceleration. Nylon ropes, with greater elongation, eliminated most of the need for additional deceleration, and with the next evolution of harnesses and metal “belayers”, belays got largely static for a while (except for the dynamic rope). Today we have the ‘soft catch’ methods, using variable friction belay devices like GriGri which allow much more deft control of the belay device unlike the ‘stitcht plate’-type designs (tc in 70s-80s gear talk). On Arnold Wexler in the AAJ, 1998: “He was one of a group of rock climbers that pioneered climbing in the Washington, D.C. area in the 1940s. When this group became the Mountaineering Section of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club, Arnold served as its Chairman for five or six years, quietly leading it through its formative stage. Through his testing of ropes and climbing equipment at the National Bureau of Standards during WW II, Arnold met a west coast climber, (then Major) Richard Leonard. Together they made the first mathematical analysis of the forces on a falling climber, his anchors, the rope, and the belayer. They created the idea of dynamic belaying— a progressive snubbing of the rope around the belayer’s body to mitigate the shock on the system. At Carderock, a local climbing area, Arnold encouraged the practice of dynamic belaying by using “Oscar,” a 150-pound dummy, who could be dropped to simulate a falling climber. The ability to do a dynamic belay undermined the prevailing ethic that the leader should never fall because of the usual fatal consequences. Now the system need not fail. This was the first step toward today’s new climbing ethic.”

Sierra Club Relents

Seeing this measured approach to climbing, the Sierra Club board shifted direction from the “tradition of John Muir” members such as William Colby (who believed in keeping ropes and gear to a minimum in the mountains), to the more progressive leadership of Francis Farquhar (who became president in 1933), whereupon the recommendations of the 1932 Committee on Rock Climbing were accepted, and Leonard became chairman of the Rock Climbing Section of San Francisco Sierra Club chapter, which became simply known as the RCS (footnote) and the Cragmont Climbing Club was abolished. In 1933, the RCS of the San Francisco chapter of the Sierra Club had over 50 members, all learning how to fall, belay, and rappel safely, and with great fun and excitement, meeting often in the rocks above Berkeley and around the Bay Area.

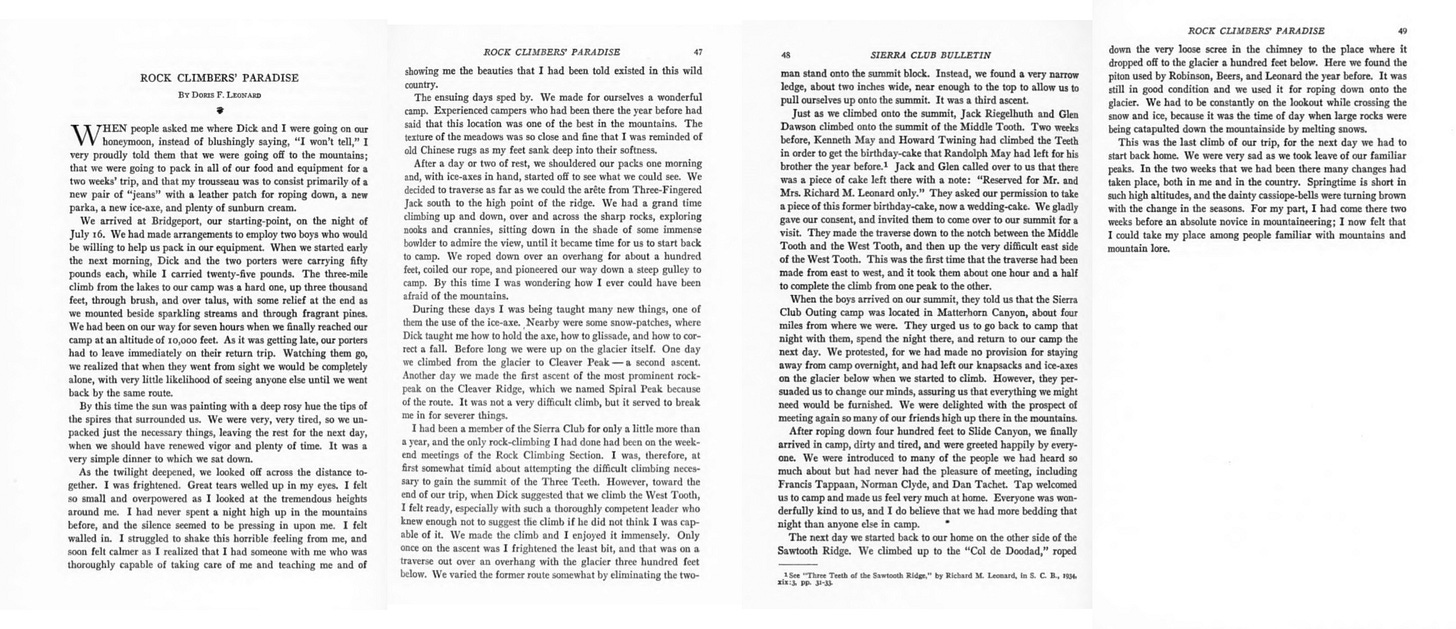

Footnote: Other Sierra Club chapters followed suit setting up technical rock climbing sections, and there were many RCS’s, even in other clubs. Glen Dawson from southern California was also learning the new methods and was an early member of the Sierra Club’s Southern California Sierra Club Chapter’s RCS. The sections were progressive with balanced genders—notable early women members include Marjory Bridge, Ruth Dyar, Barbara Welch, Doris Cocoran (who married Richard Leonard), Virginia Greever, and Jean Husted: some were signed off on 15’/25’ roped falls, and were climbing early repeats of the hardest routes being established in this period. The Yodeler was a popular newsletter with all the gossip and new climbs, and many strong partnerships formed. For more on the social dynamics, see Pilgrims of the Vertical by Joesph Taylor (2010—he does not get the 1980s quite right but the 1930s Sierra Club research is in-depth). A partial list of prolific first ascensionists spawned in this period and later: Glen Dawson, Richard Leonard, Jules Eichorn, Morgan Harris, L. Bruce Meyer, Hervey Voge, Kenneth Adam, and David Brower (18 Yosemite first ascents, 12 with Harris), Jack Arnold, Raffi Bedayan, Fritz Lippman…

As more climbers gained experience with the new methods, the RCS created a system of points for potential Yosemite leaders—all very scientific, as was their approach to safety. Members of the RCS had to prove their ability to both fall, and catch a fall, to be considered a qualified leader. Leonard reckons only 30 or 40 people were climbing at a high level in the 1930s in Yosemite, but the systems they developed would initiate a long history of global export of more efficient bigwall techniques initially developed on the walls of Yosemite Valley.

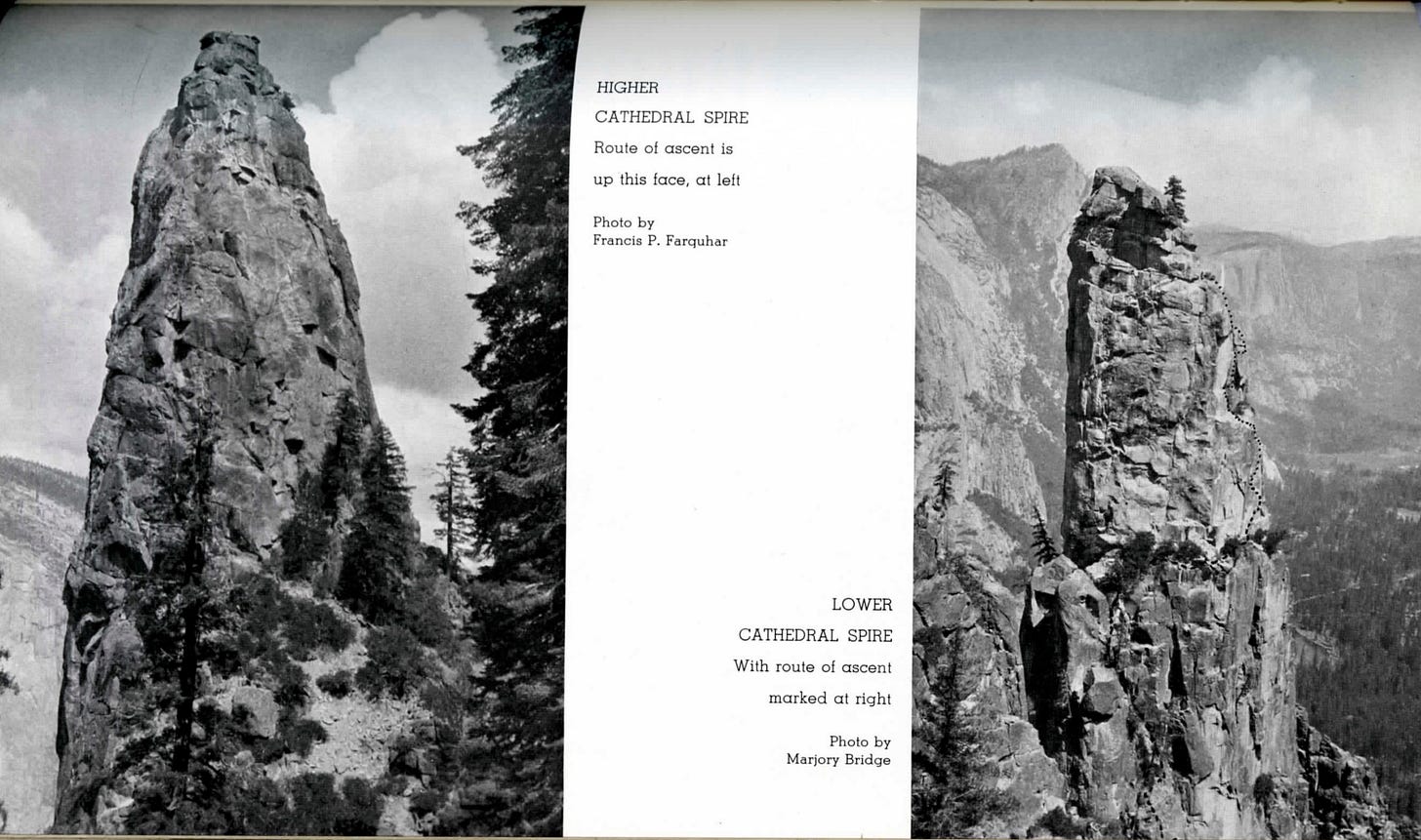

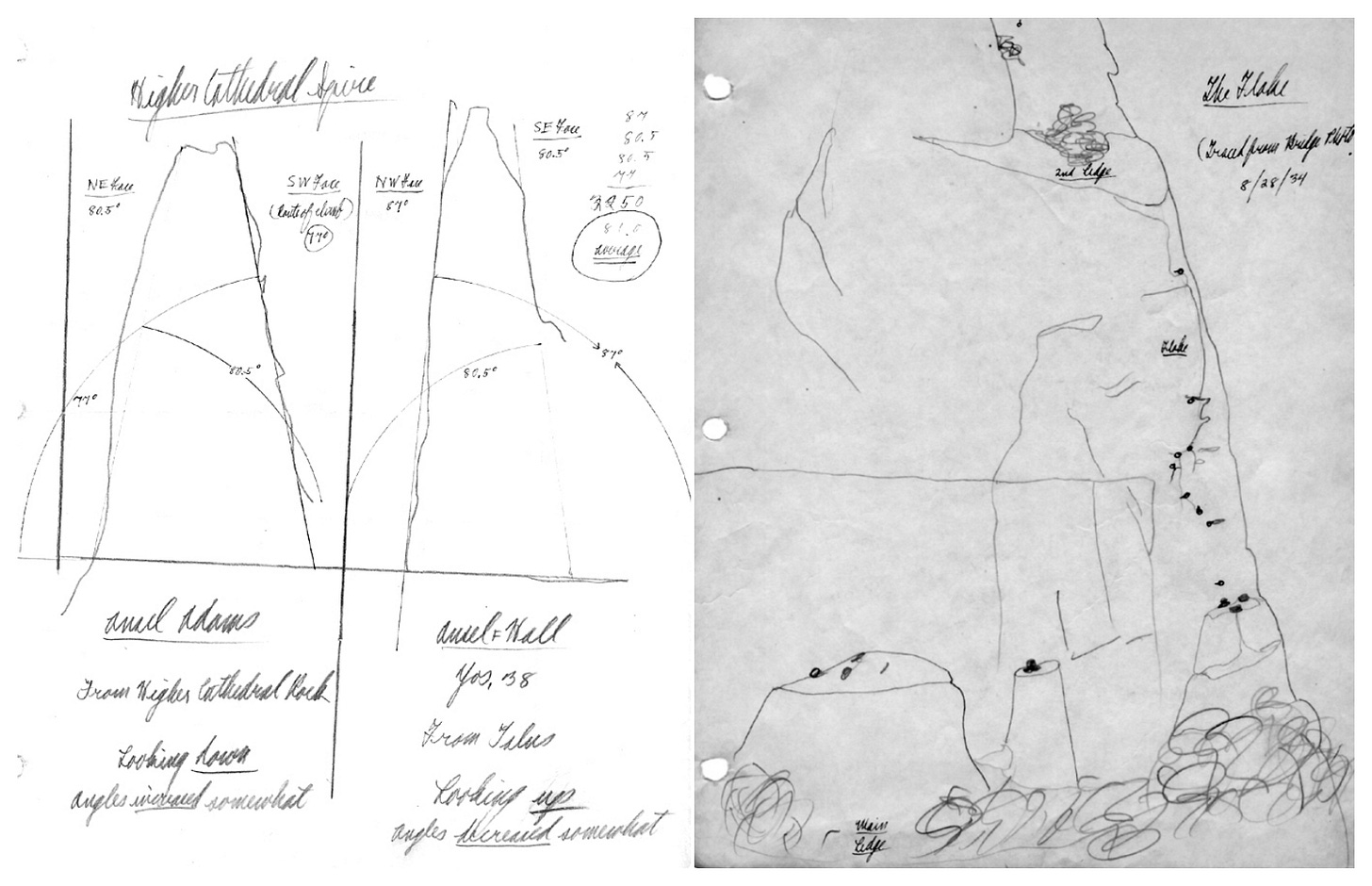

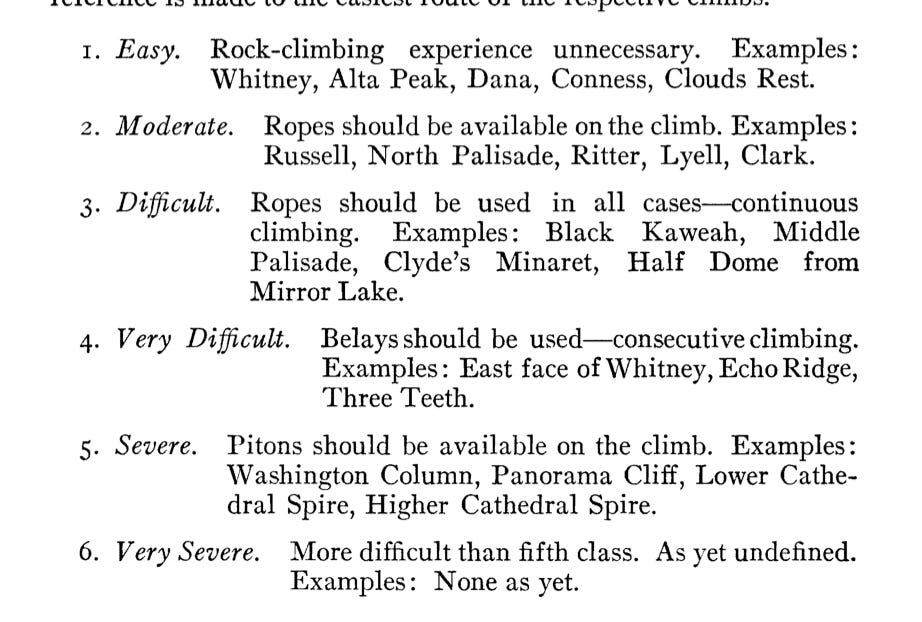

Impossible climbs made visible

In April, 1934, the RCS created a list of Yosemite rock climbs, along with potential climbs that might be possible with the new tools and techniques—some of these had been attempted, and many rated ‘E’ for ‘Extra Severe—pitons needed for safety’, and some rated ‘F’ for ‘immoral—pitons needed for direct aid’. Both Higher and Lower Cathedral Spire were rated E/F, and Leonard, Eichorn, and Robinson were the first to make an attempt in 1933.

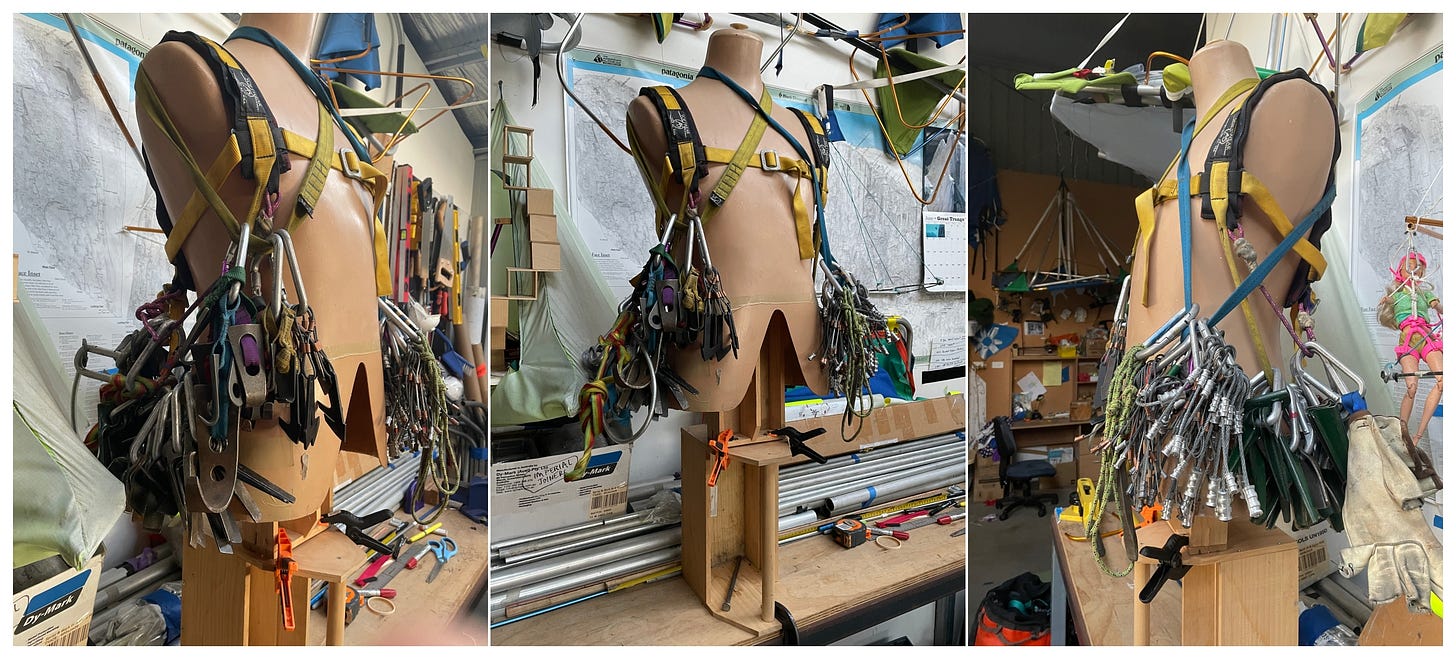

After a few attempts and ascents in Yosemite using common hardware as piton anchors (e.g. 10” hardware-store nails—which did not provide much security), the RCS crew had mastered the technique, but still needed the tools; so Leonard over the winter of 1933 made two orders of the most modern equipment from Sporthaus Schuster in Munich, which by this time had globally circulated classic catalogs (filled with information as well as product) and were known as a reputable international supplier of the best new climbing tools. And in the spring of 1934, they set out for the impossible climbs.

Creative Imagining Realised

Starting first with the creative imagining of climbing of Higher Spire, then new techniques practiced and perfected, and finally all the tools gathered, it was time for the ascent of the ‘Highest Cathedral Spire’. Richard Leonard, Jules Eichorn, and Bestor Robinson set off with 500 feet of rope, 13 carabiners, and 55 pitons of various sizes. The climb required several forays, but on April 15, 1934, in ten hours of climbing from the notch, they were standing on the summit of the taller of the two towers of stone—the largest free-standing granite formations in California. Their climb involved 800 feet of free-climbing and 10 feet of direct aid (later freed at 5.9+). The elegance of their three-person team’s ascent, much of the risk averted by technical skill, and exposed difficult climbing amidst ‘dizzingly overhanging’ features, (SCB, June, 1934), Leonard reflects, “So that started rock climbing in the western United States.” (ibid Volume 1, 1975).

The safer methods, “changed the whole philosophy of climbing,” Leonard said, “If we got up to a point where we were not quite sure we could hold a fall if it occurred, we stopped and turned back. We weren’t embarrassed, and we weren’t cowardly. We just thought we were sensible.” With this same philosophy, they further raised the technical bar with an ascent of the Lower Cathedral spire, a climb not as long, but harder, and at the upper limits of their minimize-risk philosophy (topos in appendix).

Ideas spread

The same year, 1934, Leonard published with Robert Underhill (ed.), "Piton Technique on the Cathedral Spires” for the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Bulletin describing the mechanics of the dynamic belay and technical exposé of the new, safer methods of climbing steep vertical rock (footnote). Bestor Robinson, who later wrote “I’m a rock engineer and proud of it” (AAJ 1940), summarised the nature of the climbing achievement in the June 1934 Sierra Club Bulletin:

“Looking back upon the climb, we find our greatest satisfaction in having demonstrated, at least to ourselves, that by the proper application of climbing technique, extremely difficult ascents can be made in safety. We had practiced belays and anchorages; we had tested pitons and ropes by direct falls; we had tried together the various maneuvers which we used on the peak, until three rock-scramblers had been coordinated into a team. The result was that there was no time on the entire climb, but that if any member of the party had fallen, his injuries would, at the worst, have been a few scratches and bruises.”

The idea that the famous imposing pillars of Yosemite granite could be ascended ‘alpine style,’ and with minimal risk, fundamentally changed the mindset of the climbing game, and increased awareness of the new techniques and access to tools led to historic 1930s climbing achievements in North America, including Shiprock and Mount Waddington; a whole new breed of American rock climber was spawned, complete with regional rivalries for the ‘last great climbs’. More of their envisioned climbs and history will follow, a progression that leads into the 1950s, when technical big wall climbing reaches an internationally high crescendo as a myriad of developments in tools, technique, and skill merge and combine.

Footnote: The AMC article is also the origin of “bombproof”, a term climbers often use to indicate a solid anchor system. Leonard notes that “it is essential that pitons for anchoring the belayer or for serving the leader as effective belays be ‘dynamite proof’”. Although this article is relatively rudimentary, in the years following, Leonard partnered with engineers such as Wexler on the scientific testing of ropes, pitons, and carabiners, was instrumental in the design and testing of early nylon ropes, and was a significant player in the army’s 10th Mountain Division’s tool and technique developments (tk). Perhaps more importantly, he authored concise data and articles on both tools and novel techniques which spawned further innovation. The engineer Chuck Wilts picked up this torch in the 40s and 50s.

Postscript: Leonard’s creative conservation imagining

In the following decades, Leonard continued as a leading climber and proponent of safe climbing systems. And with the same approach to climbing, he applied to environmental activism, first by imagining things others thought were impossible, then tactfully creating the safest framework for optimal chances for success, and finally strategically achieving some of the greatest environmental summits of the 20th century. Leonard was at the core of the Sierra Club’s environmental work for decades as they became America’s most effective organization for the preservation of remaining wilderness for many decades hence, and he was closely involved with the Wilderness Society, Save-the-Redwoods League, and the Conservation Law Society of America, among others. His wife Doris was also a strong leader in the growing environmental movement and they were instrumental in preventing the Echo Park Dam in Dinosaur National Monument. Some of these battles were controversial, but all were instrumental in the lead-up to the Wilderness Act of 1964.

Footnote: in 1951, at the second Sierra Club Wilderness Conference, chaired by Leonard, Howard Zahniser, executive director of Wilderness Society (1945-1964) brought up his initial recommendation for a wilderness bill. It took thirteen years of hard work to get the Wilderness Act enacted by Congress on September 4, 1964. In 1955, 1957, 1955, 1957, and 1959 Doris Leonard was in charge of the Sierra Club Wilderness conferences. Later, she founded the Conservation Associates, which led many successful preservation efforts.

“To temper the daring with the reasonable”

As in climbing, failure happens in conservation efforts. Some are only setbacks, but some end in fatalities, such as the 1901-1913 efforts to preserve Yosemite National Park’s Hetch Hetchy Valley; John Muir fought the battle to prevent Hetch Hetchy from being dammed every year for thirteen years “and he only lost it once. That is the tragedy of conservation or environmental battles,” as Leonard noted. Hetch Hetchy was damned in 1913 by the Raker Act, and soon after actually dammed.

And just as with climbing teams, strategy trade-offs and ideal objectives resulted in clashes of personality. Leonard and one earliest climbing partners, David Brower, once a team that made bold forays on great climbs, they later clashed on both counts during environmental challenges. Brower, who later became known as the Archdruid of America’s environmental movement, focused more on shifting the public’s conscience, while Leonard chose his battles carefully, preferring a negotiated behind-the-scenes legal approach, which liaised the environmental voice with the legal mandates of the land agencies. Leonard wrangled with other champions of the wilderness, like the inspiring writer and activist Martin Litton who ran dory river trips in the Grand Canyon, who had a more radical style, “I believe in playing as dirty as they do, or worse, if the end is a noble one,” Litton once said, “My feeling has always been, you can’t always win, but you can always try. And that we’re not as poor dor the battles we’ve lost as for the ones we never fought.” Both Litton and Brower did not think Leonard bold enough at times, such as during the struggle to preserve Glen Canyon (The Place No One Knew), but like his minimal-risk climbing tactics, he considered some of Brower and Litton’s efforts ‘harmful’ in the long run (i.e. too risky).

For whatever his successes and failures, Richard Leonard’s successful environmental litigation challenges, an uncharted strategy of earlier preservationists who depended solely on broad public support, became a prime mechanism for the preservation of public lands in the United States in the decades following, and his endeavors became a model for generations of leading climbers engaged in conservation and environmental preservation through organizations like the Sierra Club and the American Alpine Club. Just as it is said there are few ‘old, bold climbers’ (only old ones or young bold ones), Leonard's ability “to temper the daring with the reasonable” led to a great series of successful campaigns during his long involvement with climbing and conservation.

footnotes: “To temper the daring with the reasonable” quote describing Leonard’s ideals from Susan Schrepfeer, Leonard’s oral history Interviewer-editor (1975). Richard Leonard and David Brower began climbing together in the mid-1930s, both making early attempts on Mount Waddington as a Sierra Club outing objective in 1935, having trained on winter ascents of peaks in the Sierra Nevada. Leonard returned to Waddington in 1936, opting for a steep arete—a lower-risk objective risk but with much more technical rock climbing; the main line was a “chute 3000 feet long at an angle of about 65 degrees. Any rock or ice would come down that gulley so fast you couldn’t even see it” (Leonard, 1975—this gulley was the path of the first successful ascent). Both Leonard and Brower were involved with the climb of Shiprock in New Mexico when California and Colorado teams were both vying for the first ascent (Leonard served as the ‘intelligence officer’ for the successful ascent by David Brower, Raffi Bedayn, Bestor Robinson and John Dyer in 1939). Some of Leonard and Brower’s first ascents in Yosemite like the south arete of Arrowhead Spire in 1937 were among the hardest of the day, and their early attempts on the Lost Arrow (to the ‘First Error’) might have been the site of Yosemite’s first pendulum. For excellent data on Yosemite's historical first climbing ascents, refer to Ed Hartouni’s resources.

Author note: I once informally interviewed both David Brower and Martin Litton in 1997 and 1999, taking careful notes for an unrealized creatively imagined article I hoped to write called “Champions of the Wilderness.” Both Brower and Litton were impressive in the way they expressed the importance of the natural landscape— I will find those notes sometime. I was especially interested in Brower’s motivations and challenges in setting up Friends of the Earth in 1969, as my interview was about the same time Greg Adair, Tom Frost and I set up Friends of Yosemite Valley (1997). We also worked with a great environmental lawyer named Richard, Dick Duane, for our Camp 4 preservation efforts in 1998.

Leonard’s environmental activism approach often had three tenets, requiring constant attention to organized teamwork:

Hold the public land managers to account, often with legal means.

Arouse the public conscience to gain national support.

Squelch factional disputes by establishing catalysts for collaboration and agreement. One of the main debates in Leonard’s time, then as now, is the appropriate level of development of preserved wild lands—i.e. access to all (leading to extensive roading), none, or some.

Richard Leonard’s oral interviews on his life of climbing and environmentalism (1975)

Practice at Cragmont and Richard Leonard’s film of Lower Cathedral Spire in 1936:

Next: Pioneering sandstone bigwall ascents on the walls of Zion National Park.

“People always tell me not to be extreme. ‘Be reasonable,’ they say. But I never felt it did any good to be reasonable about anything in conservation. Because what you give away will never come back—ever.” —Martin Litton

“You can get a lot done if you don’t care who gets the credit.” —Richard Leonard

Appendix/more bigwall scrapbook images

Tools

More on ropes

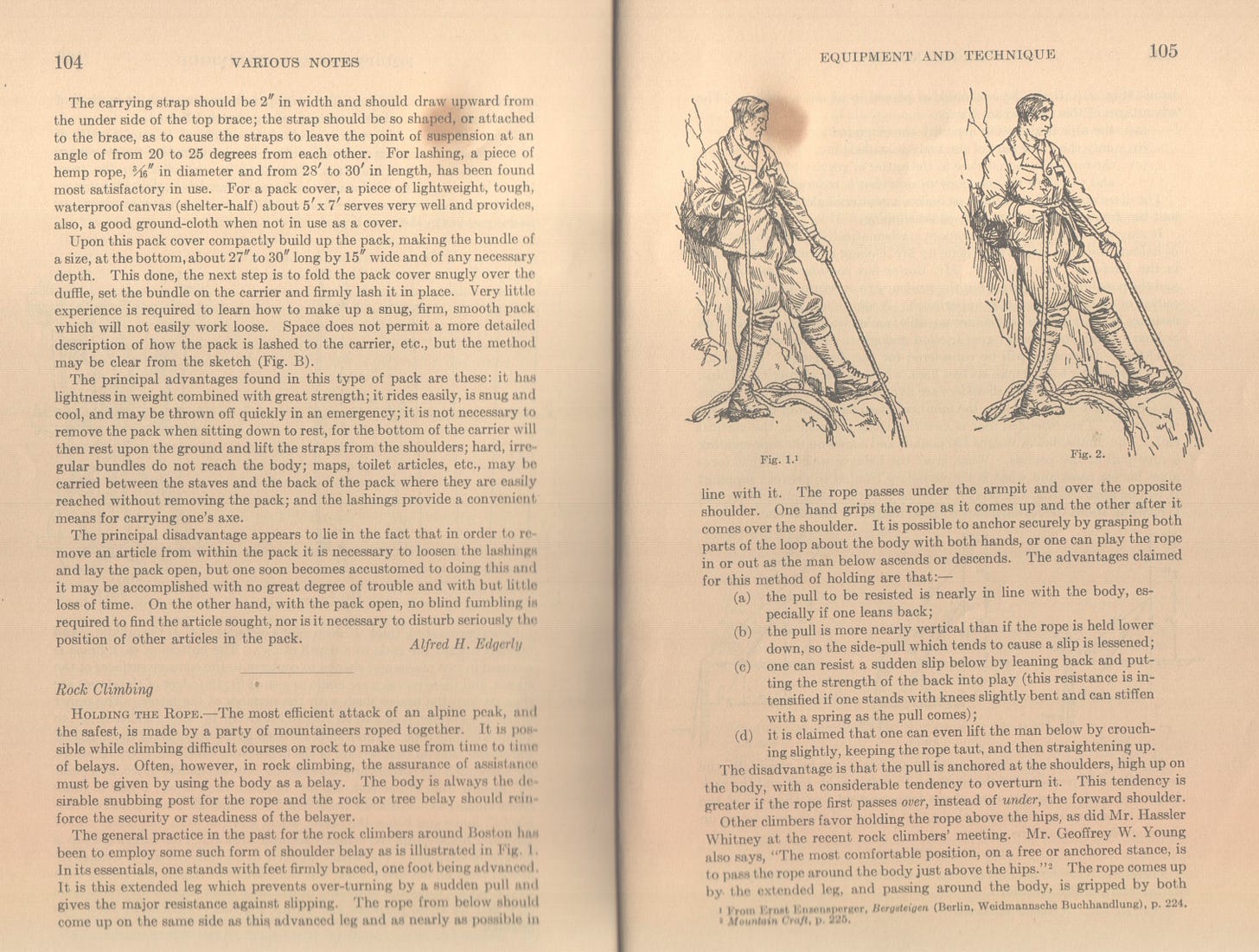

More Technique info

More California

more Colorado for prior post:

Lone Eagle Cirque is awesome in the winter. A lot of ice climbs. Don’t think many get in there in the winter. I only went once in 2004.

My father was born in Piedmont, CA in 1935 and started climbing in 1947 with the Berkeley RCS. He talked about knowing Dick Leonard and, I believe, climbed with him (I should go through his scrapbooks and journals!). In 1954 my mother and father met at Pamona College where my father was leading a belay practice and needed volunteers to jump off a balcony -- and my mother stepped forward. This got his attention, so the story goes.

That belay practice was a direct legacy of Dick Leonard's work in the 1930s. (Wow. Thanks, Dick!)