Climbing Tools and Techniques—1908 to 1939-Aid Climbing Mastery (Europe, PartB 1st draft)

Mechanical Advantage Series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

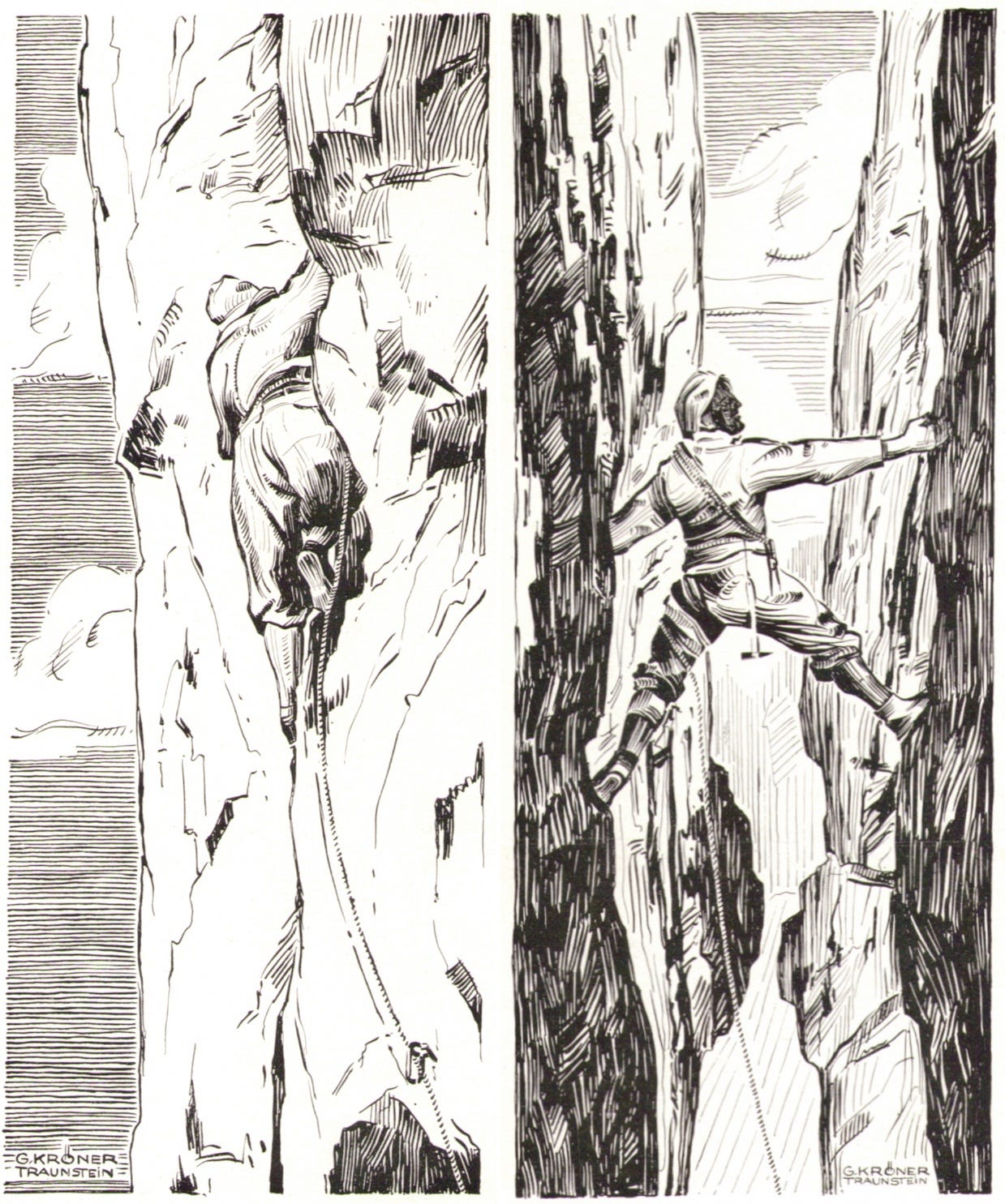

Big walls come of age with new techniques

As stronger carabiners begin to appear in the 1920s, climbers became bolder leading to a huge boom of both mostly-free and eventually, mostly-aid routes throughout the Alps well into the 1930s. International climbing organizations began exchanging more information about remote expeditionary climbing in the Andes, Caucasus, Himalayas, Canadian Rockies, and Alaska, increasing the collective knowledge regarding extended human survival in cold conditions. The tools remained mostly the same as in the final days of evanescent peace before the European war: ropes were still stiff and relatively static mostly manila-fiber ropes (though woven silk ropes were also used by those who could afford), but pitons were becoming more mass-produced and available, and with tools in hand, increased reliance on gear took place.

PITONS: Best page to read about piton technology in 1930s: https://www.karabinclimbingmuseum.com/asmu-pitons-page-one.html

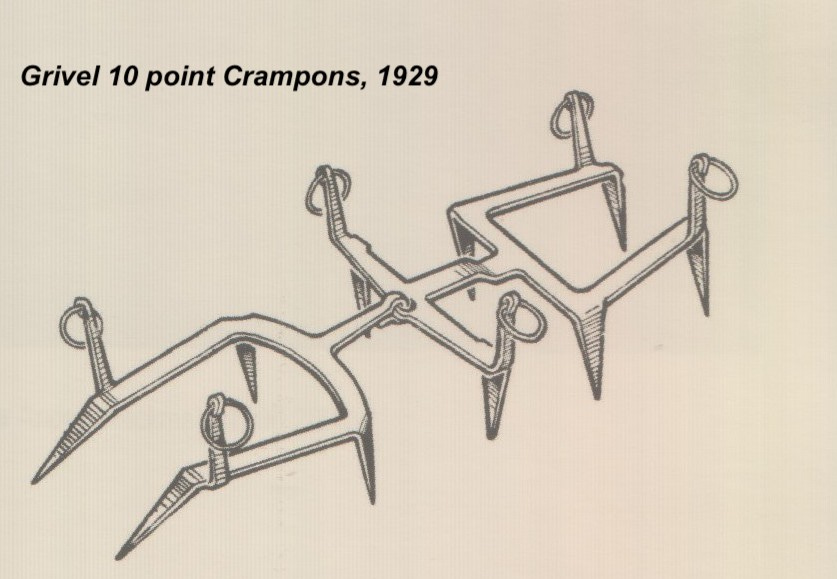

The concept of Grade VI also changed dramatically in this period. One of the outstanding alpinists of the era, Willo Welzenbach, in 1926 proposed a standard rating system (Grades I to VI) based on his experience with hundreds of routes in both the western and eastern Alps. Welzenbach was also the innovator of both ten-point crampons that fit the entire sole of the boot and shorter ice tools, which were also soon to evolve further on hard alpine big walls.

THE SPORTING WAY

In 1925, Emil Solleder and Gustl Lettenbauer climbed the northwest face of the Civetta in a day, a 3,700-foot 5.9 route in the Dolomites, carrying only fifteen pitons for protection and belays, the first route to be universally deemed a “GradeVI” by the cognoscenti. But prior to this testpiece and longest vertical rock climb of the time, big walls were coming of age, and pre-war pioneers--those who were still alive after the war--continued to push standards. Otto Herzog and Gustav Haber climbed the 1,000-foot Ha-He Dihedral on the Dreizenkenspitze in 1923, a technical big-wall route requiring two bivouacs; it was not repeated, despite many attempts, until the 1950s. Hans Fiechtl's Ypsilon Riss (5.9, A1) on the 1,200-foot north face of the Seekarlspitze was perhaps the most difficult of the era. New routes with names reflecting their character captured climbers' imaginations, and the increase in the appeal of big rock routes spawned a new breed of vertical pioneers.

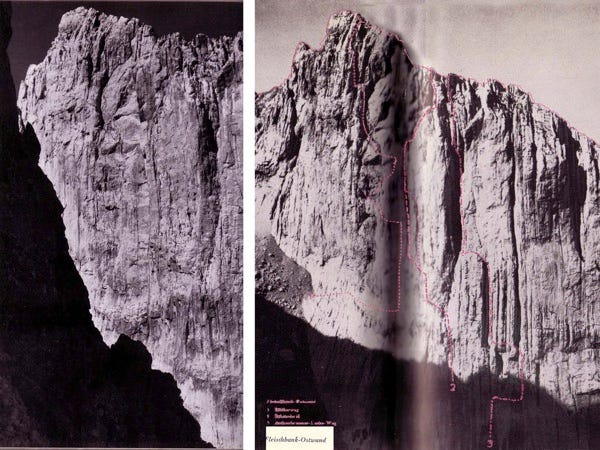

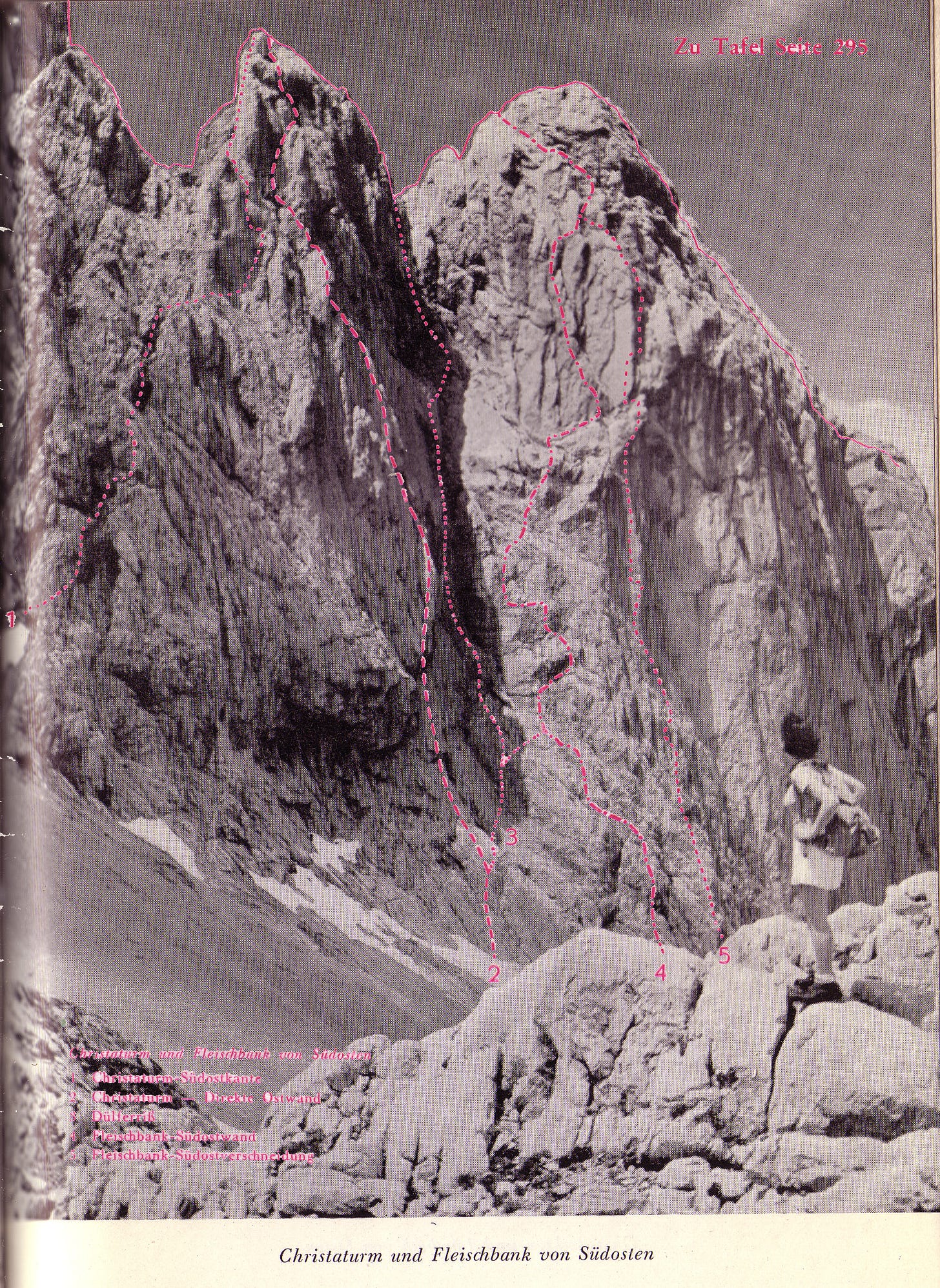

Prior to his immigration to the USA, Fritz Wiessner teamed up with Solleder and aid master Roland Rossi for some wild long rock adventures in the Alps, including the southeast face of the Fleischbank (V+), and the north wall of the Furchetta (VI). Trusting the security of the newer pitons, more climbers became willing to risk lead falls, and empowered by the improved safety on the steep stone, free climbing standards rose further.

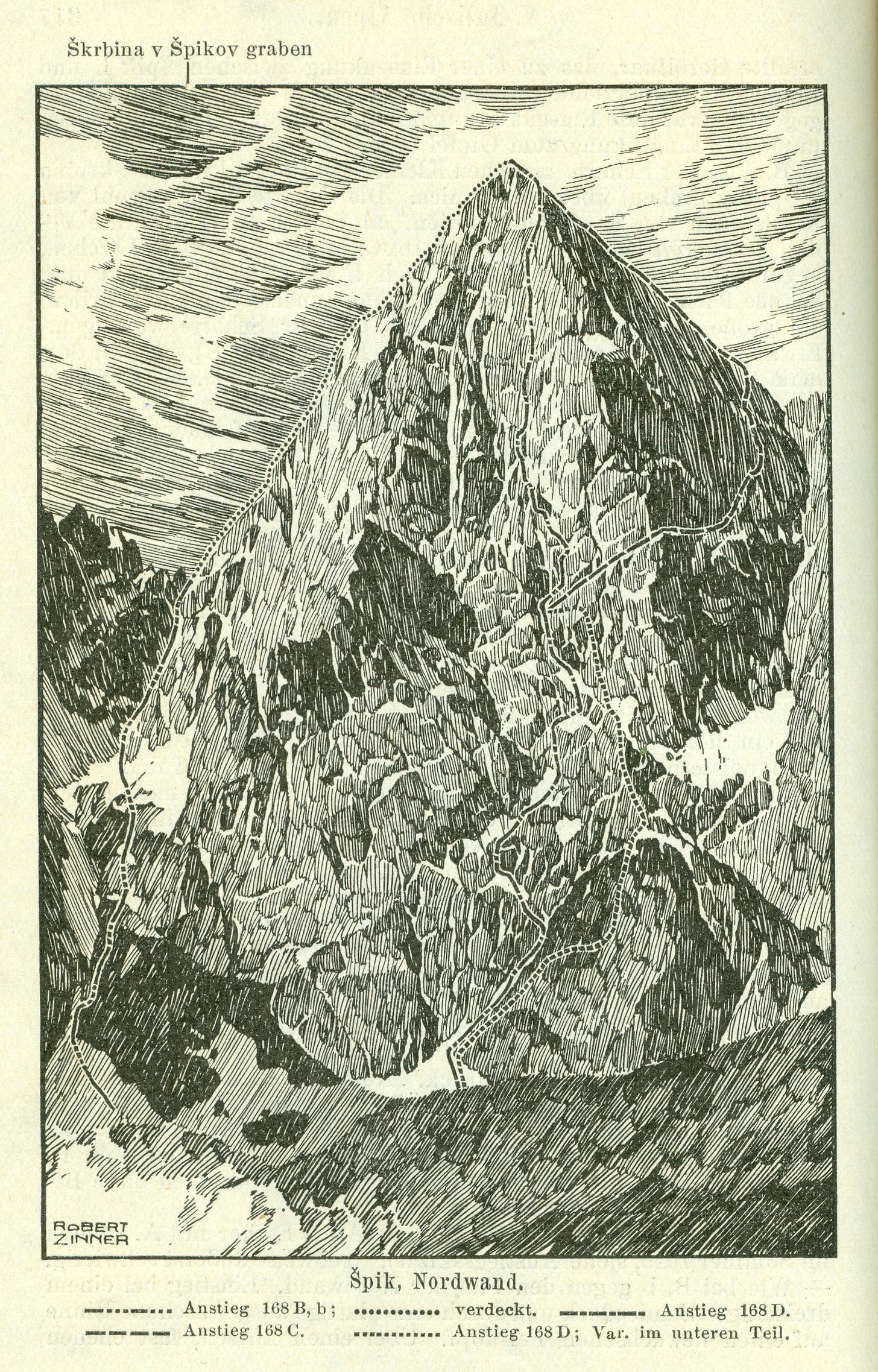

In 1926, in the Julian Alps (now part of Slovenia), Stane Tominsek and Mira Marko Debelakova spent two days climbing the technical 3,000-foot north face of the Spik, their reliance on the new gear making it possible. Tools for safe upward passage were improving, and in 1929 Luigi Micheluzzi and team climbed the Marmolada, the highest peak in the Dolomites, by its steepest route, the 1,800-foot south pillar. Pitons were used for protecting the lead climber and for occasional aid on these historic big walls, but in deference to the strict anti-piton standard of the western Alps, they were used sparingly and pure aid—going from “hook to hook”—was avoided. Truly, all these routes, and others, set new standards of boldness and commitment as early “Grade VI” routes.

IMPOSSIBLE WALLS CLIMBED

The time was right and the tools were there for the first of the famous "last great problems of the Alps." With the ascent of the north wall of the Matterhorn by the brothers Toni and Franz Schmid in 1931, another bold new era for big-wall alpinism began. In contrast to the more predicable stone of the Eastern Alps, the steep ice, snow, and mixed climbing of the great North Faces of the Alps presented new challenges in addition to the mastery of lightweight tools and techniques.

Matterhorn North Face Tension Traverse

By 1931, two methods of rope traverse had been developed:

Using a second rope for rappel and traverse per Piaz and Dülfer.

Clipping the main rope into the point of traverse, and using a carabiner as a pulley combined with a good belayer who can hold the leader and let out slack as needed.

It is not clear which technique was used for the first ascent of the North Wall of the Matterhorn, we only have Toni Schmid’s description:

Slowly but steadily I work my way up the notch. Sometimes I use the narrow ice strip, sometimes the rocks to the right of it. The body snuggles up against the smooth plates, the hands lie on flat bulges. Then the pick rages again in the hard water ice. Once, passable rocks to the left of the ramp tempt me to continue. The wall, which was easy to grip at first, soon seduced me into sloping vertical slabs. A very dangerous rope traverse brings us back to the intersection after hours of work. Then continue again. A grim struggle has set in. Meter by meter, extremely slowly. Blood spurts from the sodden and sodden fingers. But only forward, there is no turning back. Up to the summit, out of the horrible wall! The sun is already very low, and we have finally, finally, overcome the ice band. The hardest work requires a vertical, icy wall. Then we stand at the beginning of the flat summit wall. (1932 Zeitschrift—Matterhorn North Wall, Toni Schmid, München, first climb July 31 and August 1, 1931)

Re-imagining Grade VI, aid-climbing breakthroughs

In the 1911-1912 piton dispute, Paul Preuss imagined a standard to access the difficulty of a climb: “ .. a good standard for assessing the difficulty of a route – a piton coefficient – would be expressed by the ratio between the height of the face and the number of pitons!” Counting the exact number of pitons used en route became standard practice in this period, though few bothered to divide the total by the height of the face, as Preuss suggested. And in the 1930s, pitons began to appear more widely in both the western and eastern Alps, and climbers began to universally recognize that the use of anchoring systems was facilitating superb achievements on extremely difficult vertical terrain. The popularity of the sport increased, and the climbing population evolved from consisting of primarily aristocrats and guides to a broader set of athletes, doctors, lawyers, engineers, and a new breed of working-class heroes, one of whom became legendary.

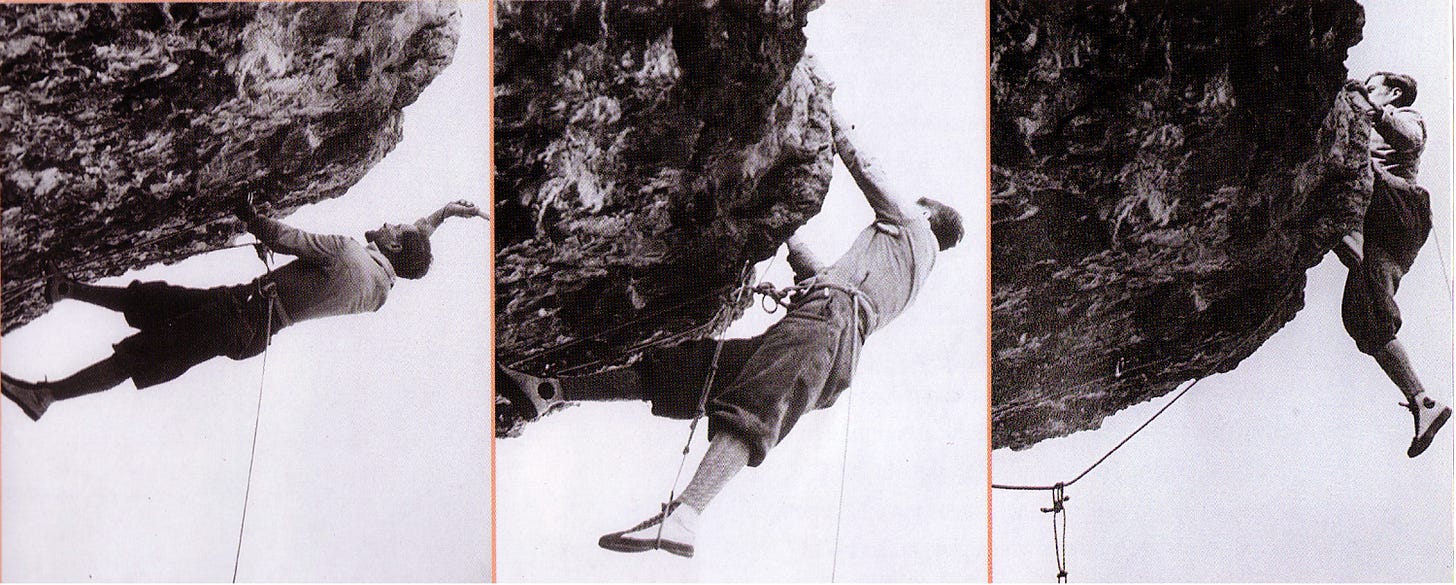

Emilio Comici was an Italian longshoreman who started with cave exploration then became an expert in the techniques pioneered by Piaz, Dülfer, Dibona, Herzog, Fiechtl, and others, and revolutionized climbing by advancing a new style well suited for the extreme cliffs of the Dolomites, and ultimately, the big walls of the world. Comici led an era leading to all the modern aid techniques, such as using multi-step aid ladders and daisy chains, ever-more complex rope maneuvers, hanging bivouacs, and climbing with a trail rope as a means to stay connected to the belayer for hauling up extra equipment. Realizing that he had a choice either to reject the use of mechanical aids or to accept them wholeheartedly, he chose the latter and made heavy use of the new tools. In 1931 he put the new systems to the test on the 3,600-foot northwest face of the Civetta, and the result was the steepest and perhaps the most difficult climb in the world (and to this day it is still a challenging twenty-six pitch vertical adventure).

In 1933, Comici’s direct line up the incredibly steep 1,500-foot north wall of the Cima Grande wavers slightly but no more than if the wind buffetted the mythical drop of water back and forth. On the lower half of the wall Comici, Giuseppe Dimai, and Angelo Dimai used just seventy-five pitons--one every ten feet, on average--more reliance on aid than ever before, but hardly excessive from an aid-climbing view, considering that the wall overhangs continuously and is composed of less-than-solid rock. Comici wrote of the route, “You know, dear Giulio, that the ideal climbing route, the elegant route, follows the falling water drop … I traced a hypothetical water drop that came down, down and splashed on the talus … the beautiful line came to us at last, when we agreed where the drop had fallen" (Comici as cited by David Smart). Inherent in routes inspired by the mythical drop--the direttissimas as they became known--is actually studying the rock, examining every little corner and crack, and mapping an elegant line of connected features.

Routes of this caliber became the prototypical “Grade VI” for the next 60 years. Comici freely shared his expertise, inspiring many with his dream of the ultimate aesthetic line. Yet he died young, never knowing that his dreams and philosophies were to create passionate splits in climbing attitudes as new technologies developed.

David Smart sums up Comici’s contribution to big wall climbing:

“Leonardo Emilio Comici led generations of climbers to the biggest rock walls in the world. Did he lead us into, or out, of a paradise of innocence? We still have to learn that, whether we are inclined to reject technology when we climb, or to accept it, all disputes with the mountain need not be settled; to leave some of our beliefs and reasons, prices we are willing to pay, and strategies of last resort on the ground.”(David Smart, Emilio Comici, Angel of the Dolomites, 2020).

Followed by a Piaz quote: “When we reach the sixth grade, we will find we have not entered the kingdom of heaven”. (Buzzati).

Age of Innovation

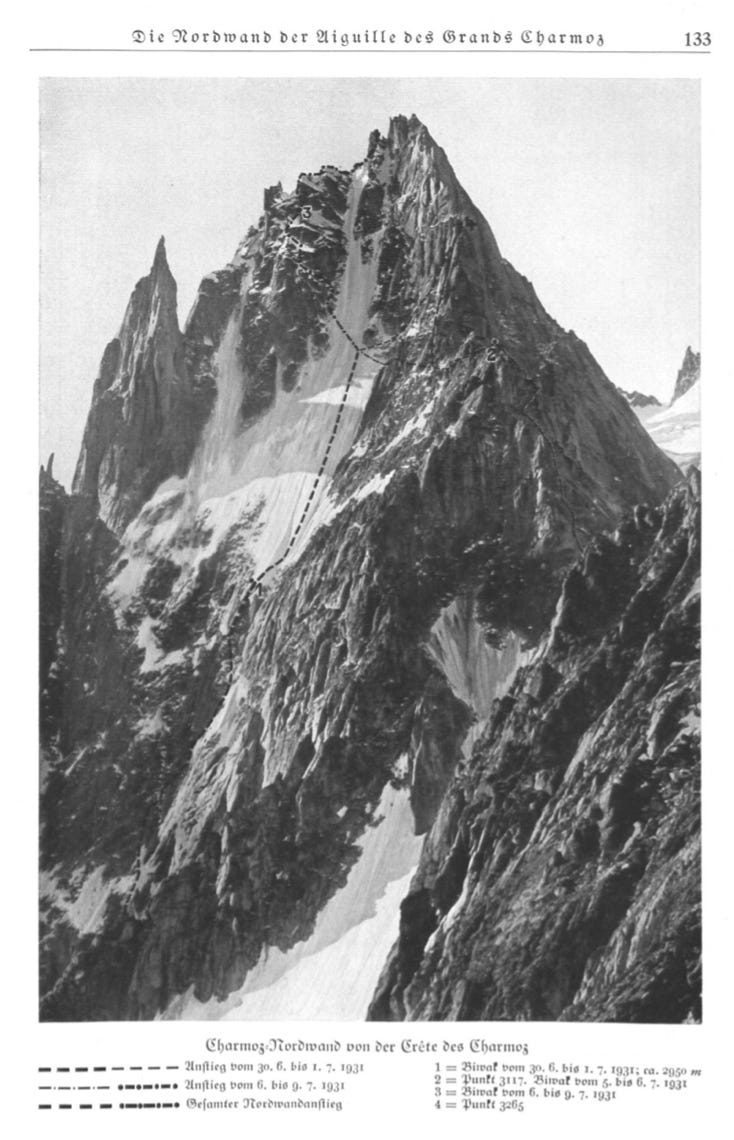

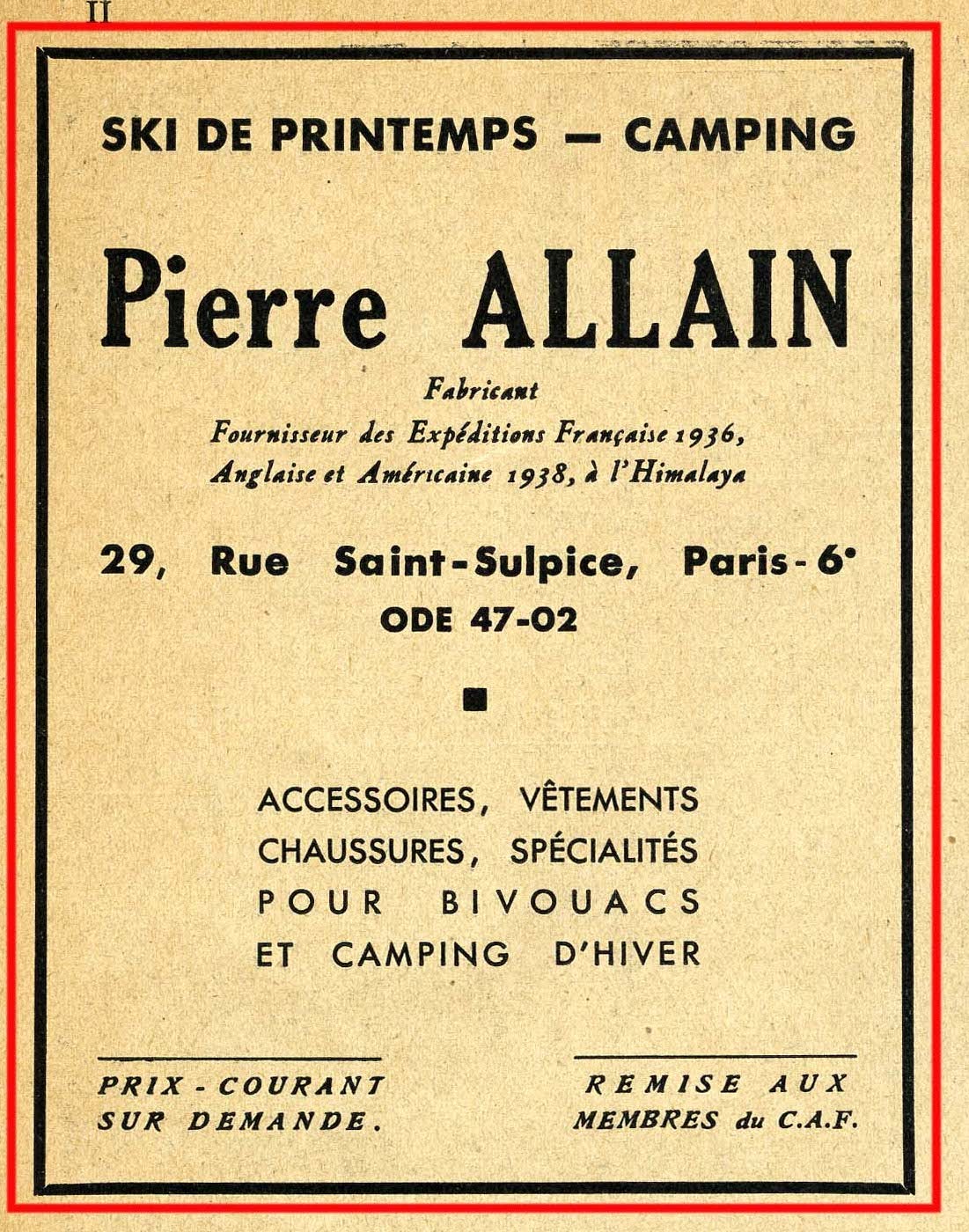

The 1930s were an age of innovation in Europe. The leader of a talented new group of climbers from Fontainebleau, Pierre Allain, developed lightweight down clothing and bivouac equipment suitable for surviving on the steep icy faces of the Alps. He also began developing early aluminum carabiners. In 1935 he made the first ascent of the cold north face of the Petit Dru, near Chamonix, with Raymond Leininger. This was a pioneering, two-day free and aid route that combined the challenges of an alpine route with the technical aspects of the Dolomite and Kaisergebirge vertical walls.

Pierre Allain still making carabiners in 1991. Source: bibliothèque municipale de Lyon

Around the same time, the Simond firm in Les Bossons began to manufacture pitons, equipping a new breed of extreme climbers. Gino Soldà, Raffaele Carlesso, Domenico Rudatis, Ettore Castiglioni, Raimund Schinko, Alfred Couttet, and Giusto Gervasutti all made incredible technical climbs during this period, but the climber who stands out most prominently, both for the quality of his routes and the breadth of his vision, was Riccardo Cassin, who also manufactured the highest quality pitons. Cassin quickly mastered aid techniques and took them to new extremes on the major routes of the period, including the Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses (with Gino Esposito and Ugo Tizzoni), the northeast face of the Piz Badile (with Esposito and Vittorio Ratti), and the north face of the Cima Ovest (with Ratti). Cassin's routes continually pushed standards of difficulty and commitment.

Eiger North Wall (part 1)

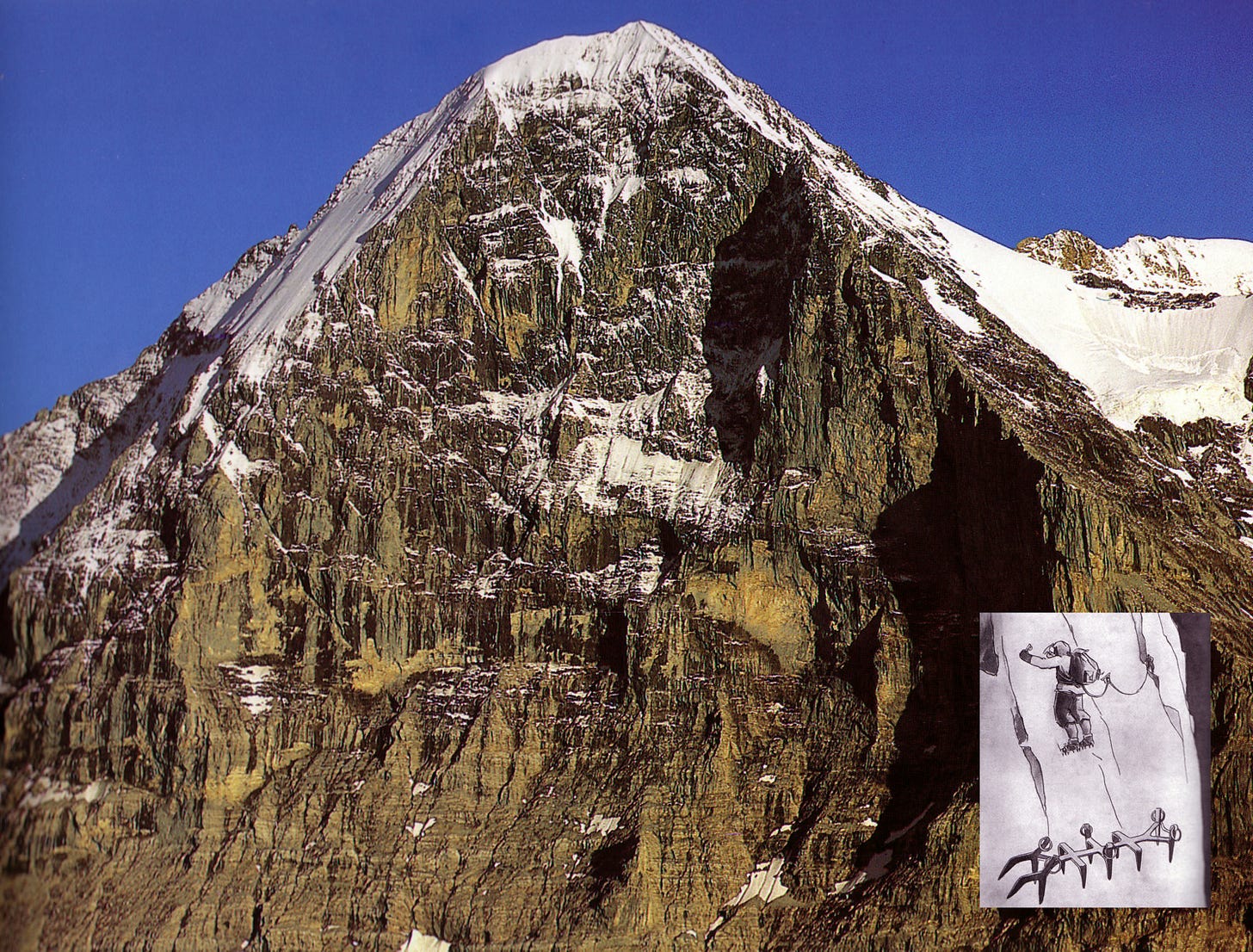

Perhaps the best description of the marriage of technology and human boldness in the interwar period came from Heinrich Harrer, in his account of the first ascent of the north face of the Eiger in 1938. Harrer had elected not to take a pair of crampons for the ascent, while his partner Fritz Kasparek had a pair of traditional "ten-points," crampons with sharp points evenly spaced around the sole of the boot. As they finished a long session of step-cutting across the Second Icefield, they were surprised to see below them Anderl Heckmair and Ludwig Vörg rapidly approaching, using the "fashionable" twelve-point crampons made by Laurent Grivel, a guide and blacksmith of Courmayeur, in 1931. The addition of two front-facing prongs allowed a climber to climb on his toes, facing forward rather than using the traditional French method of keeping the foot flat on the ice, as if frictioning up a slab. "I looked back, down our endless ladder of steps," Harrer wrote later. "Up [the Second Icefield] I saw the New Era coming at express speed; there were two men running--and I mean running, not climbing--up it." The two teams joined forces for the historic first ascent of the Eigerwand. This climb should have marked the opening of a whole new era, but the outbreak of another tragic European conflict soon put an end to the risky vertical games.

TO COME (2nd draft):

More on 1930s equipment. Techniques; double rope and aid techniques explained, additional representation of the women all-stars: Jeanne Immink, Rita Graffer, Pavla Jesih, Paula Wiesinger/Steger, Hettie Dyrhenfurth, others (again, source material is hard to find, and often secondary sources are brief), more pics and topos of routes, sharing of information, nationalistic attitudes and geopolitical aspects (Dolomites now Italy, Munich climb on Tryfan, 1936, etc.).

Link to Google MAP useful for putting peaks in context (working copy).

Photos to be cited, permission, book references, etc., most used with prior permission in my climbing history presention at Taos film festival, c1999.

Expedition Developments

Better climbing through technology is not just about improved ropes and specialized hardware. Equipment for surviving the elements contributed equally to rising standards. Before his disappearance in 1895 whilst reconnoitering Nanga Parbat in the Karakoram, Albert Mummery had developed light weight silk bivouac tents and insulating gear sufficient for living in extreme conditions. Prior to the first world war, lightweight, warm garments were evolving, and with the new all-weather equipment, climbers were prepared to spend multiple days and nights in harsh conditions to gain an ascent. They pursued steeper, longer rock climbs, and their level of commitment towards climbs reached new heights.

In the western Alps, where the mountains are more alpine in nature, artificial aid on rock was considered unsporting, but in the eastern Alps with its spectacular vertical limestone cliffs, a new standard was arising. When the Italian expedition led by the Duke of Abruzzi returned from the Karakoram in 1909, expedition photographer Vittorio Sella's lithographs of the stupendous rock walls of the Baltoro must have sparked a climber's imagination and provided additional rationale for climbing the steep cliffs at home.

notes: from my 1999 version)? In 1910, the Italian guides Angelo Dibona, Luigi Rizzi, and German clients Guido and Max Mayer (who were as equally expert and experienced as their guides) climbed the north face of Cima Una in the Dolomites, a 2600 foot big wall that broke barriers of continuous steepness and exposure. The team had developed custom pitons (Mauerhaken) and ascended with the help of new rudimentary aid techniques and rope maneuvers. Other key routes to mention… Pelmo, etc.

More Images:

LINKS to previous writing and research: