Climbing Tools and Techniques—1908 to 1939 (Europe, PartA) Myths and Legends

Mechanical Advantage Series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

European Tools and Techniques—1908 to 1939

With famous ascents like Piazturm on the Totenkirchl in 1908, the tall rock walls were eyed in new light. No longer was a continuous line of climbable rock required for ascent—by this time, climbers spent a lot of time studying the rock walls with binoculars for potential lines, and could better decipher the hazards and challenges of vertical rock, charting precise paths before setting off. When asked about careful pre-inspection of the potential routes up a mountain, Whymper once said, “None but blunderers fail to do so”. On the tall, complex and steep vertical walls in the Eastern Alps, climbers were now extending the concept of precisely mapping a climb prior to setting off to a fine art. By imagining connecting discontinuous climbable features with roped traverses, the impossible was made visible. Climbing longer walls and enchainments on routes equipped with anchors and rappels, swinging around on ropes and setting up Tyrolean traverses, and going bolder on vertical rock was also becoming more mainstream among the athletic elite, especially in the Dolomites and the North Tyrol limestone walls, where the possibilities were endless, and the challenges great.

By any other name: Style, Ethics, etc.

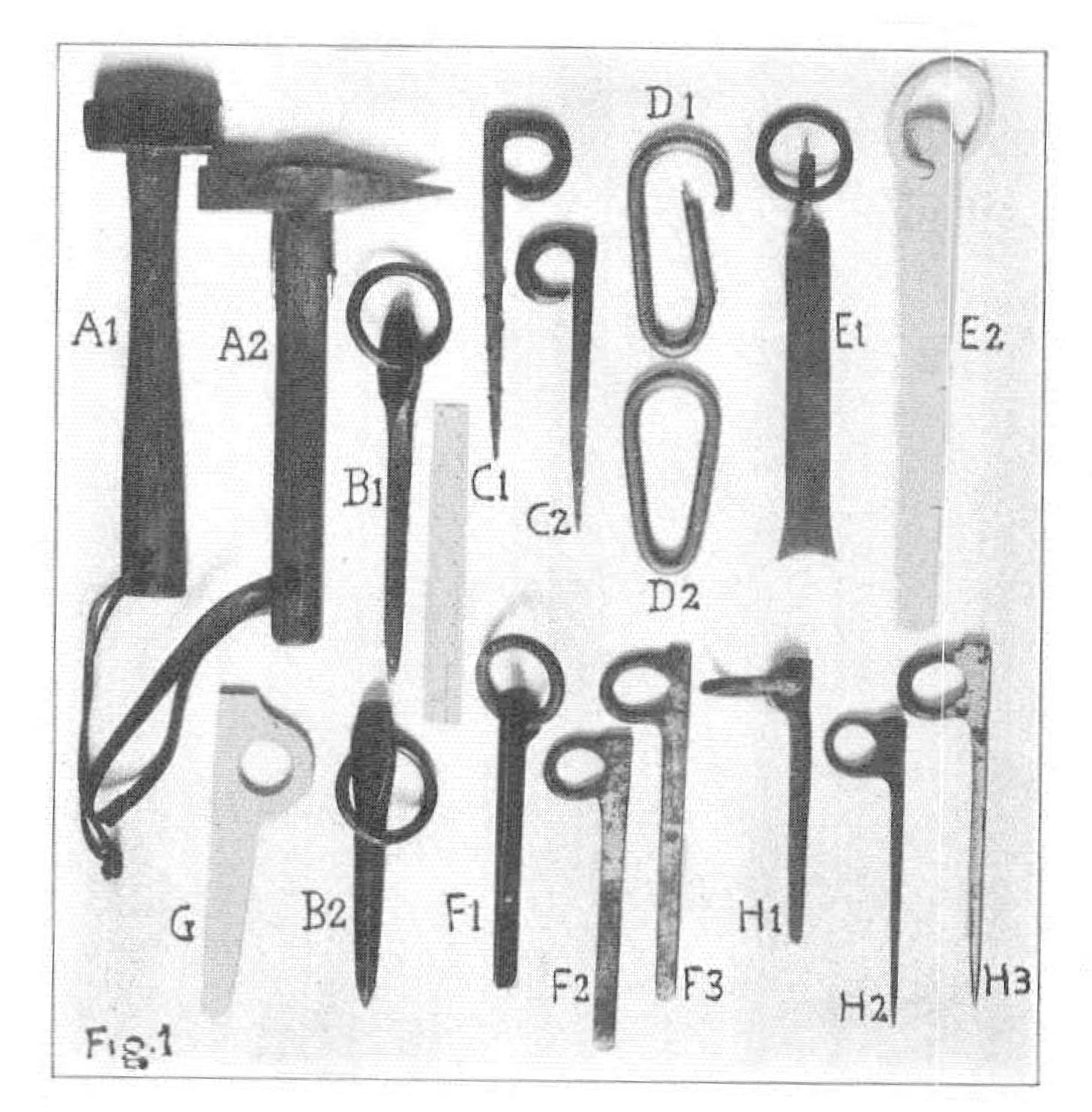

There was still a fine line between what was considered the construction of an alpine path—the early “iron paths”, some getting dynamited and steel-laddered to ease passage (now known as via ferratas, which were also booming at this time), and what was considered “sporting”. We need to remind ourselves that most of the testpieces well into the late 1920s were predominately free climbs that would still be considered quite bold today for their grade, which at the time was pushing 5.9 in Yosemite grades, and even harder in the Elbsandsteingebirge (footnote). Pure aid climbing, going from piton to piton (“hook to hook” in German) was initially still highly frowned upon, even if only used for a short section of a long climb. Tita Piaz later called those who employed such tactics as “rock gangsters”, Hans Fiechtl in particular as a “specialised nailer” and a “conjurer of forbidden passages”. Fiechtl of course is credited with the modern offset-eye piton, a piton design which Piaz also certainly adopted for his own climbs (note, however, the most common pitons from 1910-1914 appear to be simple ring pitons with welded rings, as electric welding was becoming more widespread in the pre-WWI years as the electricity grid expanded across Europe, and a flat piton with a welded ring was still the easiest piton to make). Hammers were becoming standard equipment, and most climbers had a small rack of pitons for the testpieces of the day.

footnote: the term “testpiece” used by climbers, is a route eventually generally recognized as a new standard, not always in pure difficulty in terms of something numerical, but one that stands unique in its place on the edge of the possible.

Footwear was also evolving, tighter shoes with better friction and flexibility that allowed more gymnastic climbing. The felt-soled, and later rubber-soled Kronhofer-type shoe is most often seen for the technical rock routes, though some climbers were moving toward even tighter fitting lasts without an edged sole. When leading, climbers tied into the rope with the knot on the back, to lessen the chance of breaking one’s back on a hard static rope fall, and gear—nails, hammer, and later even carabiners—were all carried in one’s pockets—jackets with big pockets were common wear (often with wide neck collars for evolving abseil techniques).

Dependence on gear evolves

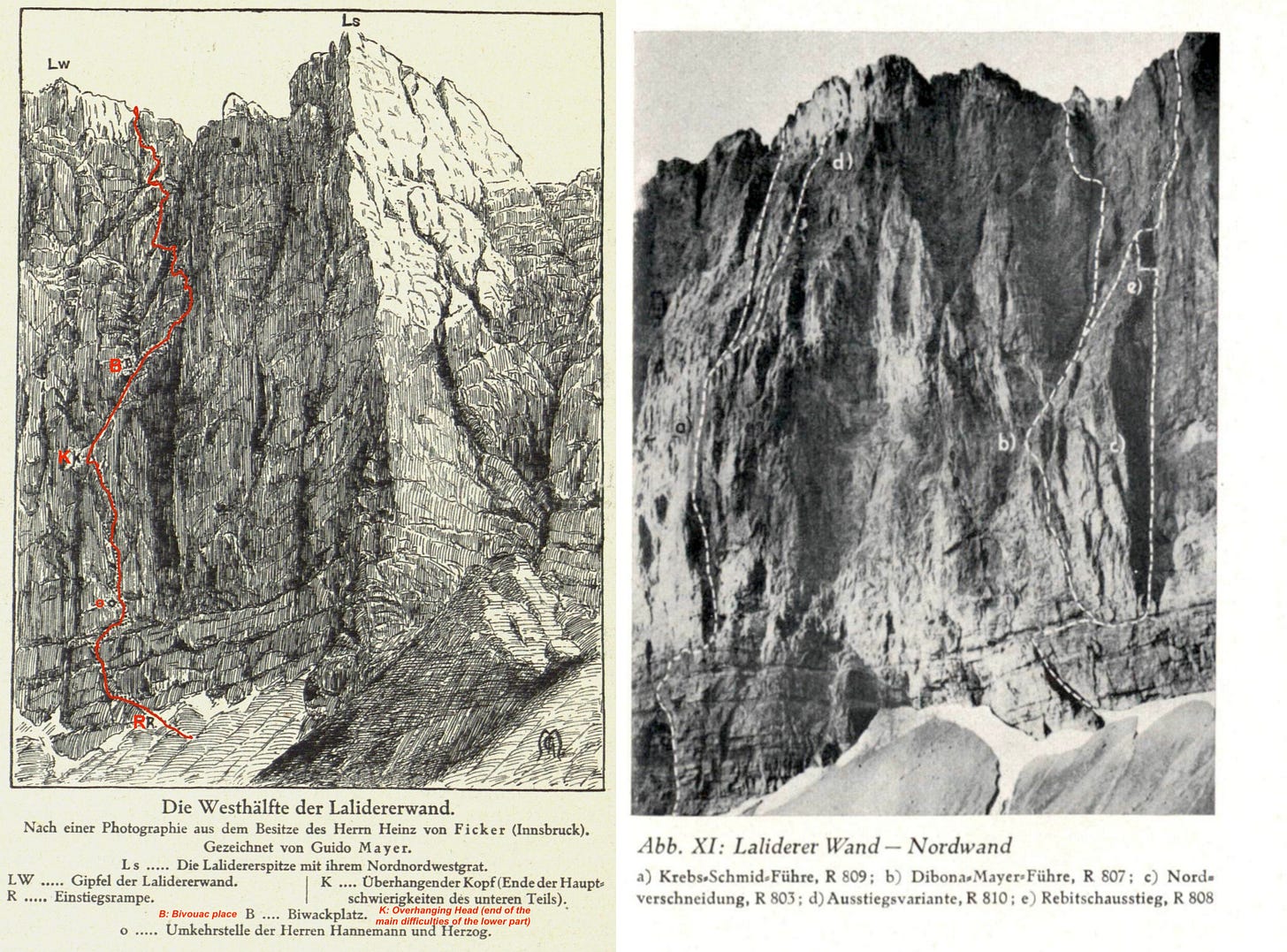

Many of the testpieces of the first decades of the 20th century involved “artificial aid”, which included pitons placed on lead to protect free climbing sections, as well as using pitons to protect diagonally downward traverses, which were not as frowned upon as to make upward progress “hook to hook” in short sections of the climb. One of the pioneers who further pushed new frontiers of the fusion of technology and human ability on intimidating rock walls was Angelo Dibona, one of the great guides in this era. His route on the 800m north wall of the Laliderer in the Karwendel range with Guido and Max Mayer, and Luigi Rizzi required a bivouac on route and set new standards of difficulty on the long routes. According to Max Mayer in the 1912 report of the route, they “only” had 15 pitons, and one section in particular required complex piton and rope work to overcome a tricky downward rope traverse (marked K for “overhanging head”—Kopf—on left topo below):

…the first rest after almost 8 hours of hardest climbing. After that, Angelo takes up the fight again and, after a vain attempt to climb the overhang directly in front of us, descends a few meters to the left, well secured, into a shallow, overhanging, obtuse- angled corner (in the mentioned report of the German Alps newspaper», the term «extraordinarily difficult» does not refer to the overhanging intersection, but rather to the downward traverse to the left). With great effort and with the help of several hooks, he conquers inch by inch until it is no longer possible to climb in a straight line. With pounding hearts we follow the bold as, pulling the double rope through a ring higher up, he takes the terrible step to the left, to the mirror-smooth edge. Reluctantly, the right foot exchanges the secure hold of the hook for the almost vertical plate of the bead. Suddenly a slight crunch lent the fateful gliding of the foot on unsupported rock; but already Dibona is happily on and withdraws from our field of vision. A few minutes of extreme suspense and agonizing excitement pass, then Angelo announces victory: "I'm in the gorge!" We breathe a sigh of relief when the next message comes: "Now things are going better!" Now a new question arises: descending over this point, which perhaps even surpasses the heaviest upper overhang on the ödstein north face in the Ennstal, where the safety rope from above must be described as an extremely questionable one. If we want to take the same route as Dibona, the night might still surprise us here; the thought of commuting across to the gorge and climbing directly up its smooth drop is also discarded. So we have to shimmy across using a fixed, crooked rope, which, apart from the impossibility of using the rope, also works smoothly, so that we can soon stand together and see that Dibona is right, really better walkable rock follows. After we the loosened the ropes that bound us, and continue our way in two separate teams, and after a short time, climbing in or next to the gorge, we reach a larger rubble dump, the white rock of which often indicates falling rocks, from which we fortunately were completely spared remain. Rather exhausted we settle down here on Mother Earth, in the happy knowledge of having completed our day's work. (MAX MAYER, 1912)

The description of Dibona’s traverse on Laliderer sounds awkward and risky. Today we call such climbing A0, when you are relying on gear to maneuver, and often making complex free moves, sometimes jumps, in conjunction with tension from the rope (footnote).

footnote: once I was walking along the base of Tiger Wall in Arapiles, and I looked up and saw Malcolm Matheson setting up another outrageous roof climb of the highest difficulty. The way he was swinging around in space, moving deftly up and down and across sometimes with only a fingertip holding him back from an airy pendulum in space, and realized that the A0 of the past had been superseded by the climbers establishing the most difficult sport climbs of today. His acrobatics were amazing. In the 1980s, we would have called such maneuvers A0+.

Using the rope-sling-piton system of climbing, more technical challenges were possible, that still involved a highly skilled technique, and most importantly, enabled efficient fast and light climbing. Many disparaged the new techniques as “mere engineering”, because of course, that is exactly what they are. It took a keen mind to envision rope safety systems on the ever-more complex rock climbing, finding safe places to belay, maneuvering onto easier ground, all in the steepest rock imaginable. “Airy” is the one word that describes it best, because there is a feeling of flying, the perspective takes a strong will to situate, and a heightened sense of fear adds to the puzzle. Accidents were increasing too, and this will be a separate research task, because then, as now, accidents were reported in journals with analysis of failure modes, so that the climbing communities that were sharing the information were also the ones most advancing the tools and techniques in terms of safety and efficiency, knowledge that began in the Tyrol and Dolomites, and took decades to filter to the rest of the world.

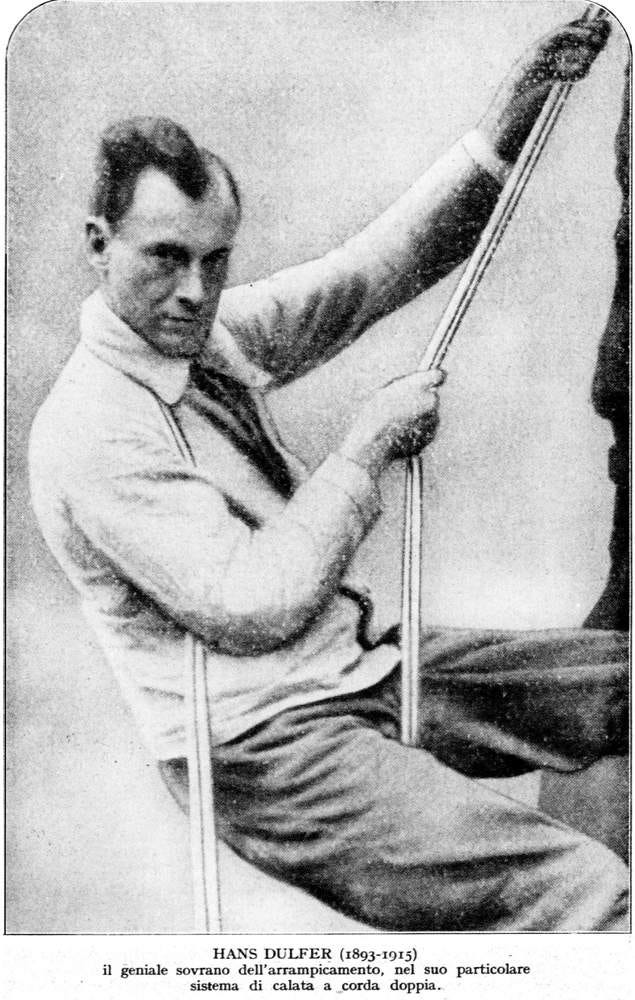

Hans Dülfer (1892-1915)

In the years prior to strong reliable carabiners, Hans Dülfer is the one to advance the art of vertical rope engineering significantly by creating the first controlled rope traverse system for ever-bigger lateral moves on the steep. But before we look at exactly what Dülfer was up to, we need to clear up a couple myths.

Myth #1: Dülfersitz is not the Dülfersitz

Author’s Note: Like many, I had a common misconception of rappeling evolution, but have since discovered the Dülfersitz is not the Dülfersitz. At the Telluride Mountaineering School, run by Dave Farny, from 1974-1978, we learned (and later taught) climbing techniques in the sequence as they had been learned for decades—first top-roping and down climbing steep slabs with heavy boots, then swinging leads and simul-climbing on long easy climbs like the Wham Ridge on Vestal, and eventually graduating to climb modern routes with clean protection and climbing shoes with greats like Henry Barber. Although aluminum figure-eight descending devices were widely available in the 1970s, we rarely had harnesses—we generally tied into the rope with a bowline on a bight—so our only means of roped descent was the classic well-practiced rappel/abseil technique known as the Dülfersitz, as depicted in every published textbook on climbing of the era, for example, as in the classic climbing instructional, Basic Rockcraft, by Royal Robbins.

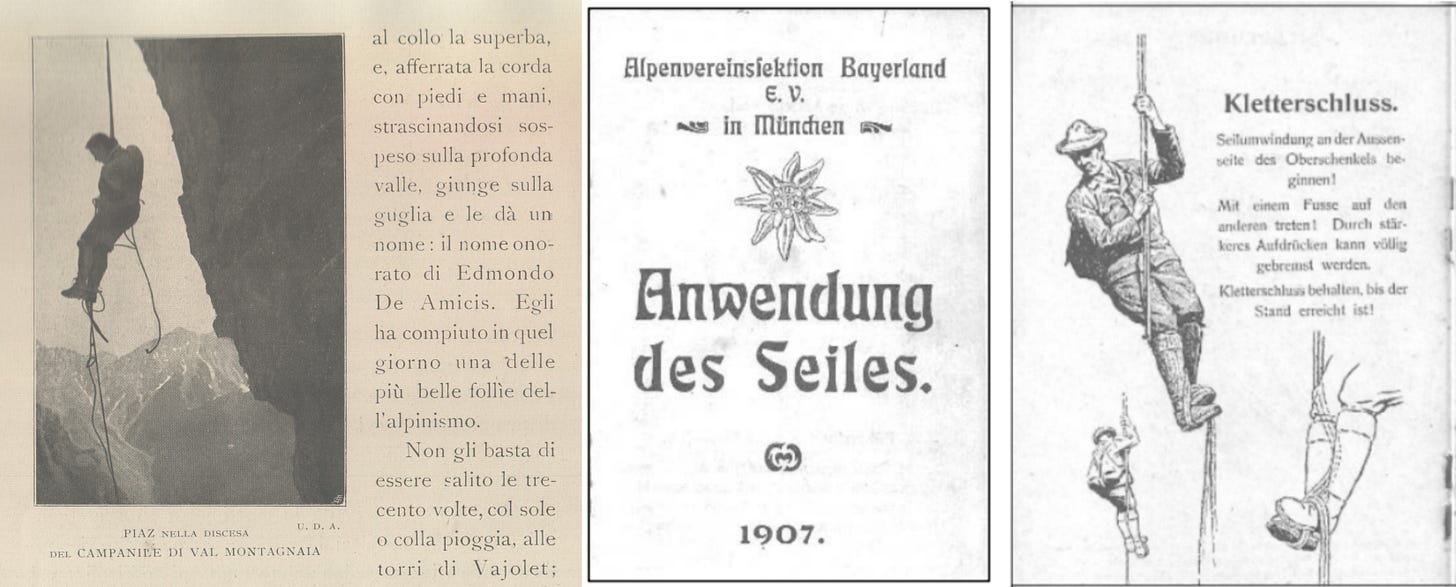

In the early literature, there are only rare depictions of the under-the-arm method of abseil as illustrated above, which is one of many variant rope body-break systems seen in early technique books and articles. Various configurations of the rope passing around the legs and body offer varied advantages and disadvantages in terms of strength required vs. the amount of skin potentially lost from burns from the rope passing over the shoulder or hips under tension. Piaz’s upside-down rappel was probably the most spectacular:

Abseil Evolution

The “down-roping” (abseil) technique generally employed in the first decade of the 20th century on the famous long, free-hanging abseils is a gymnasium technique with the rope wrapped around the foot and with one leg locking the rope with the other leg, and called the “Kletterschluss”. This technique requires very good core strength to maintain a safe controlled descent.

A natural evolution of abseil/rappel techniques soon occurred, and early literature shows techniques involving wrapping the rope around different parts of the body to provide friction and control. In the 1910s, abseil methods with the rope wrapping around the body begin to appear, and the main method of abseil was with the rope wrapped twice around the leg and over the shoulder:

The real Dülfersitz: the self-belayed tension traverse

What Dülfer was most famous for at the time, and well into the next decades, was a specific variant of these techniques, with the rope passing around the neck—designed not so much as for pure descent, but rather a means of traversing involving tensioned maneuvering with a separate, second rope—perhaps a “self-belayed tension traverse” would be a more accurate description of the innovation Dülfer brought to the table.

Climbers using around-the-neck rope braking techniques are often depicted with shirts or jackets with tall collars, a necessity for the Dülfer around-the-neck technique. The method developed by Dülfer is a very effective rope control system when the climber needs optimal use of the hands to move across rock under tension.

Dülfer’s system involves a separate, second rope for lowering on and traversing, and his technique was made famous when he employed it on his groundbreaking routes on the Fleischbank in 1912 and the direct line on the Totenkirchl in 1913 in the Kaisergebirge, both of which involved previously unimaginable traverses across blank rock. The technique became more widespread in the Eastern Alps, as it was far safer than having a tensioned climbing rope over a Seilring—a rope sling that could be cut and burned by friction—so climbers began bringing a second, shorter rope for such maneuvers in the era before strong carabiners. The technique could also be used for a straight rappel as Platz illustrates, but it is most effective as a self-belay when moving across rock due to the optimal freedom of both hands.

The Dülfer technique is clearly outlined and described in a 1931 Lo Scarpone article (Italian, full article and translation in appendix):

1912 Fleischbank (400m) and 1913 Totenkirchl (600m)

Whereas the original Piazwand on the west wall of the Totenkirchl had one tension traverse reliant on a point of aid, Dülfer took the rope traverse technique further with more complex, longer and more difficult tension traverses to link up challenging features, creating visionary lines in the Kaisergebirge range.

And a visionary line up the center of the Totenkirchl in 1913, with the feared “Nose Traverse”.

As tension traverse techniques evolved, more and more climbers were testing out these new techniques on smaller crags, and understanding the potential. Beginning in the 1920s, the Seilquergang, as it became known, was illustrated and described in many journals. Karl Prusik wrote a book on techniques in 1929 and considered the rope traverse one of six basic techniques that should be formally taught to every beginner climber along with knots, belaying, rappelling, hauling a pack and creating an anchor with pitons.

Early Belays and Pendulums.

With all the new reliance on pitons and ropes, belay techniques needed to be safe and reliable. Over the shoulder, arm wraps, and even behind the back (hip belays) are described in the literature, in contrast to earlier depictions, where the belayer appears to be simply holding up the rope for the leader. People were definitely aware of the high impact forces a falling body generates, as many sad accident reports reflect, and climbers did not attempt to belay precariously as in the days prior to lightweight piton systems.

Hans Fiechtl and Otto Herzog famously introduced a carabiner to the rope traverse technique, used on the Schüsselkarspitze in 1913 (topo in appendix)—a tension traverse so bold, that it became known as a pendulum (footnote). But before we look at their innovation and other climbs of new standards, we need to clear up another myth.

Footnote: The boundary between a pendulum and a tension traverse can be blurry. Nowadays, we call maneuvers a pendulum if it involves significant running back and forth to gain momentum, but both pendulums and pure tension traverses can be equally difficult as they both may require the same deft climbing at the end of the traverse. In other words, the “getting there” is easy, the “getting established at the end” is the hard part, and requires a careful belayer.

MYTH # 2—on the invention of CARABINERS

Snap-links, for want of a better general name, evolved as steel and manufacturing techniques evolved. In 1887, the Teplitzer hut was stocked with “rescue rope with karabiner”, and in 1898, a climbing harness system adopted from civil fire brigades, “with strong rings and karabiner hooks” was recommended for abseil in the German/Austrian Alpine Club communications. Patents for strong snap-links and carabiners, mostly forged designs, go back to the 1850s; most of these were complex, expensive to make, and often heavy. Some climbers had them, but not many (see appendix for 1892 example).

On the other hand, more commonly found clips available for other purposes (such as the famous hooks used to strap a carbine rifle to one’s back) were not “full-strength” from a climber’s perspective and were shunned for climbing, but in the Eastern Alps they were all called Karabinerhaken (carabineer’s hook) or simply Karabiner. In 1898 it was also noted, “On the use of karabiners, opinions are very divided. Most karabiners have a closure held by spring, and might rightly be regarded by some as not sufficiently reliable.” This view did not change until the 1920s when stronger carabiners made from better steels become more widely available. In other words, there was no “everyday” snap link that could be adopted for climbing, and specialised, stronger ones were costly and heavy (footnote).

Footnote; the best of the early ones depicted in the early literature look similar in strength to today’s toy carabiners, usually marked “not for climbing”—they might hold body weight, but not much more. After WWI stronger steel became more widely available.

What was used, much more often, were strong forged steel rings, specified as 8mm thick and 70mm in diameter, that could “be obtained at any ironmongers" (1910).

“Eisenringen” (forged and welded steel rings) are also often described in the early literature as a means to reduce rope drag on both leads and on rappels. But for most climbing, the “Seilring” or knotted rope sling (also called a “vine cord”) was still the main way of connecting the rope to anchors. If the system is not dynamic, a simple and light rope sling is an efficient system. But as climbers were leading farther above gear, and starting to use the rope to swing around the rock, tools for a more dynamic system were envisioned and developed. The idea often seen in short histories that the carabiner was invented to clip into the Fiechtl offset-eye piton design, or vice versa, is just plain wrong—the offset eye was advantageous for other reasons (see pitons chapter), and the early literature on making pitons specify an offset eye with rounded edges to best secure with a hemp- or manila- rope sling.

Early carabiners were “body-weight” only

Early carabiners were used as a quick way to secure oneself, mostly noted as a point of connection and useful on overhanging, awkward moves where clipping oneself into a piton (instead of relying on the belayer) with a sling can assist in making the next move, or by being used as a mini-pulley, so some could pull themselves up to an anchor more easily. Their initial use in climbing was for body-weight-only applications, not to clip a piton anchor into the lead rope; instead, slings were preferred. In 1928, a Mitteilungen article on dynamic fall rope testing cites an example of a snap hook breaking on a fall of only one meter (with a 80kg load), and notes that the materials were the main issue, concluding, “the resistance of such hooks against shock loads during free falls is very low. It is lower than climbing ropes.”

On the other hand, the relatively weak but useful carabiners commonly used at the time are noted for many other applications on the vertical, and in 1920, after explaining how the carabiner can be used as a point of temporary security or as a pulley, the Mitteilungen recommends “the climber must therefore carry with him: 3-4 wall hooks, 2-3 carabiners, and a hammer” while noting, “and also rope slings, which often serve well!” (full text in Appendix). The convenience of a carabiner to clip into a piton at the end of a tension traverse, when only one hand might be free, is noted in the early literature, and some climbers used carabiners to help direct the rope in conjunction with a body belay. Interestingly, there is no evidence that carabiners were ever used to rack pitons for the lead climber until later in the 1920s, as most gear was still stashed in one’s pockets for climbs of the earlier era.

The myth of Herzog inventing the carabiner appears to come from a secondary source, of someone remembering him using carabiners in 1910. Instead of “inventing the carabiner”, Herzog was more likely initially well-known for his introduction of the carabiner for a tension traverse: a rope system with a climber on one end of a carabiner pulley and a belayer on the other, which enabled new levels of control and distance for acrobatic swinging around on the high cliffs. More on that soon.

In short, it is not very clear who invented the first modern “climbing carabiner”, one strong enough to withstand typical dynamic loads in climbing. Curiously, Franz Stöger (1883-1935) the keeper of the Stripsenjoch hut near the Totenkirchl, which he climbed over 200 times, is noted as “the inventor of the karabiner ring” in his obituary (AAJ, 1937), but not much else is readily known of Stöger. There is also evidence that early strong carabiners for climbing were first developed in the Elbstandsteingebirge (see appendix). But most early references to carabiners are for body-weight-only applications, mostly as a point of temporary and quick attachment to an anchor.

What is more clear, however, is that toward the late-1920s full-strength carabiners first became more widely available and directly led to even greater breakthroughs in the mountains, such as the first ascents of the North Face of the Matterhorn and Eiger in the 1930s, which both involved roped tension traverses and other maneuvering using utilizing lightweight rope-carabiner-piton systems.

Whew!

Now that we have gotten a few myths out of the way, we can look at the fun new ways climbers used the ongoing innovations in climbing equipment on the big walls of the world (including going more in-depth of the rope acrobatics the early pioneers) then onto the new frontiers during the 1920s and 1930s in the European Alps.

Next Part: more pioneering routes pre-WWI years, and then into the 1920s: double rope aid technique develops.

Appendixes:

LINKS to previous posts:

In the Beginning: Subtle Means and Engines

The Modern Era of Mountaineering (1786)

American Trail Builders, 1800's

Rope Technology in the 19th century

Mizzi Langer -- first advertised rock climbing pitons (Mauerhaken)

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1a

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1b

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1c

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1d

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution-part 1e

Tita Piaz-Alpinisto Acrobatico (Piaz PartA)

Tita Piaz-Speed Climber and Rope Acrobat (Piaz PartB)

Tita Piaz-Guide and Rigging Expert (Piaz PartC)

Tita Piaz—Big Wall Climber (Piaz PartD)