1930s Climbing Tools (Europe, PartC)

Mechanical Advantage Series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

This chapter will cover more the specific tools and techniques developed by the end of the 1930s and used on all the big wall breakthroughs of the period.

Styles Refine and Diverge

In the 1930s, three basic climbing styles prevailed and were advanced in various areas by talented climbers leading to the development of new tools and techniques:

True free climbing: no pitons, ropes and slings used only for safety. In the UK, this style was advanced considerably, starting with the famous Napes Needle, and carried on to various cliffs with varied challenges around Britain. In the sandstone cliffs of Elbsandsteingebirge, the style became very bold with fixed drilled protection placed with community consensus.

Artificial climbing: climbing with pitons placed on lead. Often the line between “free” and “aid” blurred, what we would call “French Free” today (sorry France), also often called A0, i.e. the Nose-in-a-day on El Capitan often climbed at 5.11 A0. This style of climbing prioritises efficiency and speed of ascent.

Pure Aid climbing: with Comici’s ascents of the north wall of Cima Grande and SE arete of Cima Piccola di Lavaredo in August and September 1933, involving pure aid (hook to hook) climbing, a new style was born.

The best big wall climbers of the 1930s were skilled up in all three of these styles, and we will see how the further development of these techniques, primarily in the Dolomites, led to big wall breakthroughs all over the world. But before we get into the new tools and techniques developed specifically for aid climbing, let’s review the general development of gear in the 1930s.

Bolts

No proper history of bolts used for rock climbing has been unveiled. Bolts in rock pre-date the sport of climbing by millennia, going back to the stone age to gain vertical access. The technology advanced during the mining and bridge-building boom of the industrial age, and new concepts including expansion bolts were adopted for climbing (the earliest bolts were often cemented in place). As we have seen, mountain climbing in the 1800s saw many routes becoming heavily equipped for future ascents, such as the Zugspitze and many other prototypical tourist routes and via ferratas that exist today. Tita Piaz possibly had one the most lightweight climbing bolt kits back in the early 1900s for his many ascents, noting his carrier loaded with all the tools of the trade, and later referencing drilling a hole with a steel chisel to place a piton (see Piaz chapters). Interestingly, a recent book on climbing technology, Alpinisme, La Saga Des Inventions (Gilles Modica), seems to avoid the topic for the most part, apparently grouping bolts with pitons as “des pitons à expansion” (otherwise a good reference book on many topics, esepcially on the French developments, with the most comprehensive history of ice tools—crampons, ice axes, and hardware).

From a climbing first-ascent perspective, bolts and pitons are distinct tools: bolts can be drilled anywhere, while pitons require a natural feature. On remote big walls, a small rack of pitons is still essential equipment for alpine-style ascents, as the proper size piton can be placed speedily and securely to overcome sections as efficiently as possible, taking the time to drill only when absolutely necessary. Early climbers knew this, even Dülfer in 1913 is reported to have carried a stone drill (probably a chisel) on his groundbreaking direct route on the west wall of Totenkirchl, but it was never needed or used. Unlike the early Eastern Alps climber’s complete openness in reporting their piton usage, bolts are rarely mentioned in the early literature, though their use became known from later reports. Their official inauguration to the climbing world was not to come for several generations.

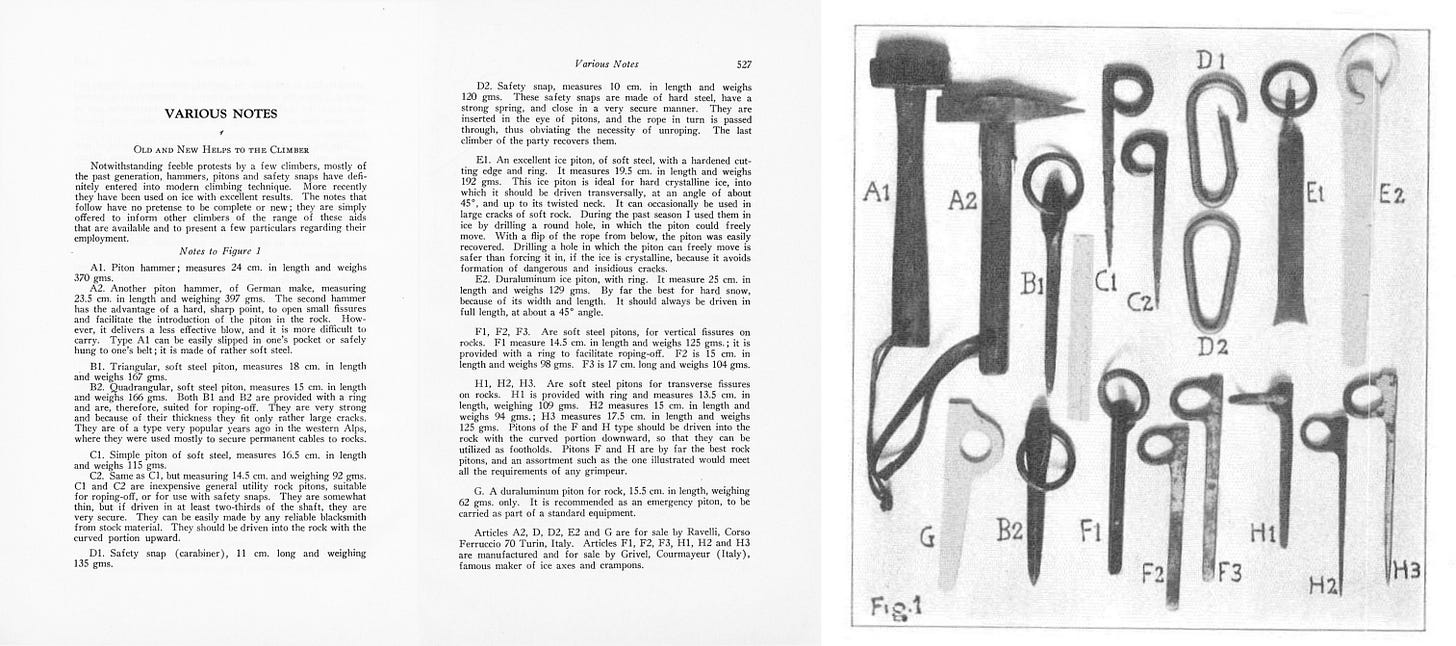

Early bolts specifically manufactured specifically for rock climbing were made by Grivel in the late 1920s, as reported in the 1932 American Alpine Journal in an article called “Old and New Helps to the Climber” by Max Stumia. Never accepted as a mainstream primary climbing tool until the late 1980s, bolts are a touchy subject and often a point of pride to ignore in the literature, but later in this series I will outline the state of the art of bolting technology in specific eras, as a lightweight bolt kit is also key to efficient alpine big wall climbing.

For the big wall testpieces of the 1930s, bolts were not widely used, as the more natural lines were still being discovered, so will only briefly be touched on in this section.

Pitons 1930s

During this period, many climbers and small blacksmith shops produced rock climbing pitons, primarily of the Fiechtl flat and horizontal designs of various thicknesses and lengths (see prior chapters). Hermann Huber (b. 1930, inventor at Salewa since 1945), writes, “the ASMü Schuster pitons were more or less monopolistic in Germany for a while. At the workshops in the Bad Obendorf Allgäu mountains, it was not quite industrial mass production, but they must have been quite busy following market demand.” The Sporthaus Schuster printed catalogs and mailed them internationally, and in the 1920s and 1930s, the ASMü pitons found their way all over the globe, from the USA and Canada to the Himalaya and Karakoram (evidence TKO). A collective of blacksmiths in Fulpmes (Tryol Stubaital) were also producing commercial hardware during this period.

Based on the writings of masters-of-pitoncraft Riccardo Cassin and others, pitons placed by the lead climber were most often removed by the second climber, who also carried a hammer, though with the era’s soft-steel pitons (footnote) hammered into undulating limestone cracks, often pitons would get “fixed” —left in place—if hammered in too securely. Indeed, popular climbs got progressively “equipped” (and thus easier) with each successive ascent. A typical rack in this era included 15-20 pitons of various sizes, and half as many carabiners. Note that angle pitons do not appear until the 1940s, probably first made as US Army ring-angle pitons during WWII and tested on Seneca rocks in West Virginia (where thousands of pitons were placed during 10th Mountain Division trainings under the leadership of Raffi Bedayn).

Footnote: also, to remind, the pre-1950 pitons are often mistakenly called “soft-iron” in the literature; however, these pitons, since the turn of the 19th/20th century, were actually made from commonly available mild steels (i.e. 1020). When Salathe began producing pitons of the harder and stronger chrome-moly (4130) steel in the 1940s, people began calling the earlier steel pitons “soft-iron” to differentiate. See previous piton chapters for more details.

Carabiner State-of-the-Art, 1930s

Even though one of Ernst Platz’s incredible drawn tutorials dated to 1924 shows an oval-shaped carabiner (see image below), the original oval carabiner that we envision today—something strong and as reliable as all the other components in the system— a strong steel full-size oval—was probably first produced under the August Schuster brand ASMü (August Schuster München) in the 1930s. The interlocking “toothed” gate design was state-of-the art until well into the 1940s (footnote). Note that the “leader must not fall” adage applied as equally to the early weak carabiners as to the stiff, non-dynamic ropes; the more common smaller pear-shaped carabiners would likely have been the weakest link in the system for the lead climbs in this era.

Footnote: Raffi Bedayn designed aluminum oval carabiners with an improved pinned gate design—similar to many modern carabiners sold today—and were produced soon after WWII. Pierre Allain designed interesting gate-closure designs, as well as early aluminum “D” carabiners (TKO).

Tidbit: even well into the 1970s, Karabiner is spelled with a “k” even in English literature. The French adopted the word Mousqueton, named after another type of short-barrelled rifle, even though the original German word Karabinerhaken was derived from the French word carbine, the gun carried by French military carabineers (or carabiniers—soldiers armed with a carbine rifle), and clipped for carrying with a snap-hook. By the late 1970s, carabiner with a “c” becomes universally fashionable in English literature. {The Italian word for a carabiner is moschettone.}

Racking systems 1930s

…pictures are worth a thousand words:

Ropes 1930s

When we think of natural fiber ropes, we often think of the scratchy hemp ropes we see in hardware stores today. But prior to nylon climbing ropes (appearing after WWII), natural fiber ropes were generally produced at a much greater standard with quality fiber preparation and production. In the 1930s, the best natural-fibre, three-strand ropes were adequate for safe-climbing. Georg Sixt made drop tests on various diameter ropes, and in 1926 it was reported that the best Italian hemp ropes could withstand a 75kg mass falling 15 meters with 12-15cm extension—a long fall that would injure most humans from the high impact forces—yet the rope would not break. Climbers were also beginning to understand the dynamics of climbing rope systems: the energy generated by a fall, and how the energy was absorbed by various parts of the system (see this 1933 article). Quality silk ropes at the time were also strong enough for climbing, and much more flexible, yet 20 to 40 times the cost of a good hemp rope. Standard rope lengths were 40m and the standard diameter for a single climbing rope was 12mm. With the double lead-rope technique (described below), two 10mm diameter ropes were commonly used. (DuÖAV and CAI).

Belay Techniques (photo and caption):

Climbing and Traversing Techniques

By 1931, two methods of rope traverse had been developed:

Using a second rope for abseil and traverse per Piaz and Dülfer.

Clipping the lead rope(s) into a point of traverse with carabiner as a directional pulley, combined with a good belayer who provides tension to hold the leader and gives slack as needed. Prusik shows the rope traverse with a one-rope system in 1929 as is standard today on big walls, but most climbers in the 1930s were moving to a double rope system, where both ropes belayed the leader.

Note: With the redundancy of belay ropes, smaller lighter rope diameters could be used, with two 40-meter 10mm ropes becoming standard equipment for this style of climbing. Double lead-rope technique, and still a favourite system for free climbs with tricky protection, also reduces the need for slings to prevent rope drag.

We see both methods in the 1930s:

Dülfer rope traverse method illustrated:

Double rope tension traverse method on the Totenkrichl Nose Traverse:

Double Rope Techniques

The double lead-rope technique, using two equal full-length lead ropes, superseded the Dülfer method of taking a shorter second rope only for abseil, and soon evolved into a new universal lead technique. The double lead rope system provided more versatility, and became preferred for the pure-aid technique that Comici, Gervasutti, Cassin and others developed in the 1930s for the biggest and steepest walls. Riccardo Cassin records the double-rope climbing method in his biography:

Every sport climber knows the feeling of being cinched up with the rope by the belayer, using artificial assistance to reposition and discover the means to climb new vertical ground while working out the moves on a hard climb—this was the standard of the 1930s “Grade VI” style—climbing that was not considered “free” nor “aid”, but just a modern climbing style, using points of protection and ropes for tension to monkey around, while ascending inspiring cliffs in search for difficulty. Rudatis notes in 1931 regarding the overall “homogenous” balance of difficulties: “It is fair to remember that driving nails is hard work and fully worth as much as overcoming rock difficulty without artificial aids.”

Leigh Ortenberger explains it well in the 1964 American Alpine Journal, not long after the term “free-climbing” came back into general use (footnote):

“This line between free and artificial climbing is often rather fine indeed and in different areas is defined differently. In the 1920’s and 1930’s probably few ever considered that help from a second’s knee or shoulders, or even an ice axe jammed in a crack, represented “artificial” climbing. In parts of Europe climbing is not considered artificial until slings or stirrups are used along with pitons or expansion anchors; the mere use of tension from such ironmongery is not recognized as something above and beyond “ free” climbing.”

Early use of the term “free-climbing” refers to climbing, without the need for ropes or gear (what would be closest to “onsight solo climbing” today. Witzenmann wrote in the 1902 DuÖAV: "For me, of course, a mountain is "inaccessible" when it cannot be climbed in free climbing. With artificial ads, wall hooks, thrown ropes and the like, eventually every rock peak can be reached". Also Interesting to note that today, ice tools jammed in cracks is once again considered “free”.

Authors note: This double rope climbing technique persisted even into the 1990s in Europe for routes with short sections of aid. I once offered one of our expedition members to Trango some new 4-step and 5-step A5 aiders and daisy chains for his planned climb of Nameless, but he preferred not having such encumbrances and described his double-rope aid method of clipping one rope into each piece, pulling himself up like a 2:1 pulley, then with the belayer holding him tight, finding a higher placement for the other rope. On the route, he was cinched up on a stopper in a marginal placement halfway up the route, and as he was making the next placement under tension, a shift of weight caused the stopper to pull, resulting in a broken ankle and a heroic rescue by his partner. The method is of course more secure with pitons, and less secure with unidirectional clean climbing tools. It also loads each piece with roughly twice the force.

Aid Climbing

Evolving from using pitons as an extra handhold or as a pulley point as a way to make continuous upward progress, further aids were developed to make upward progress more efficient; these become standard big wall equipment, primarily aid ladders and “daisy chains”—shorter cords attached directly to the harness to clip into gear (sometimes called a “cows tail”). A new age of big wall climbing began, and with the new tools and techniques so much more was possible, and bold pioneers took these techniques to alpine and remote big wall climbs all over the world.

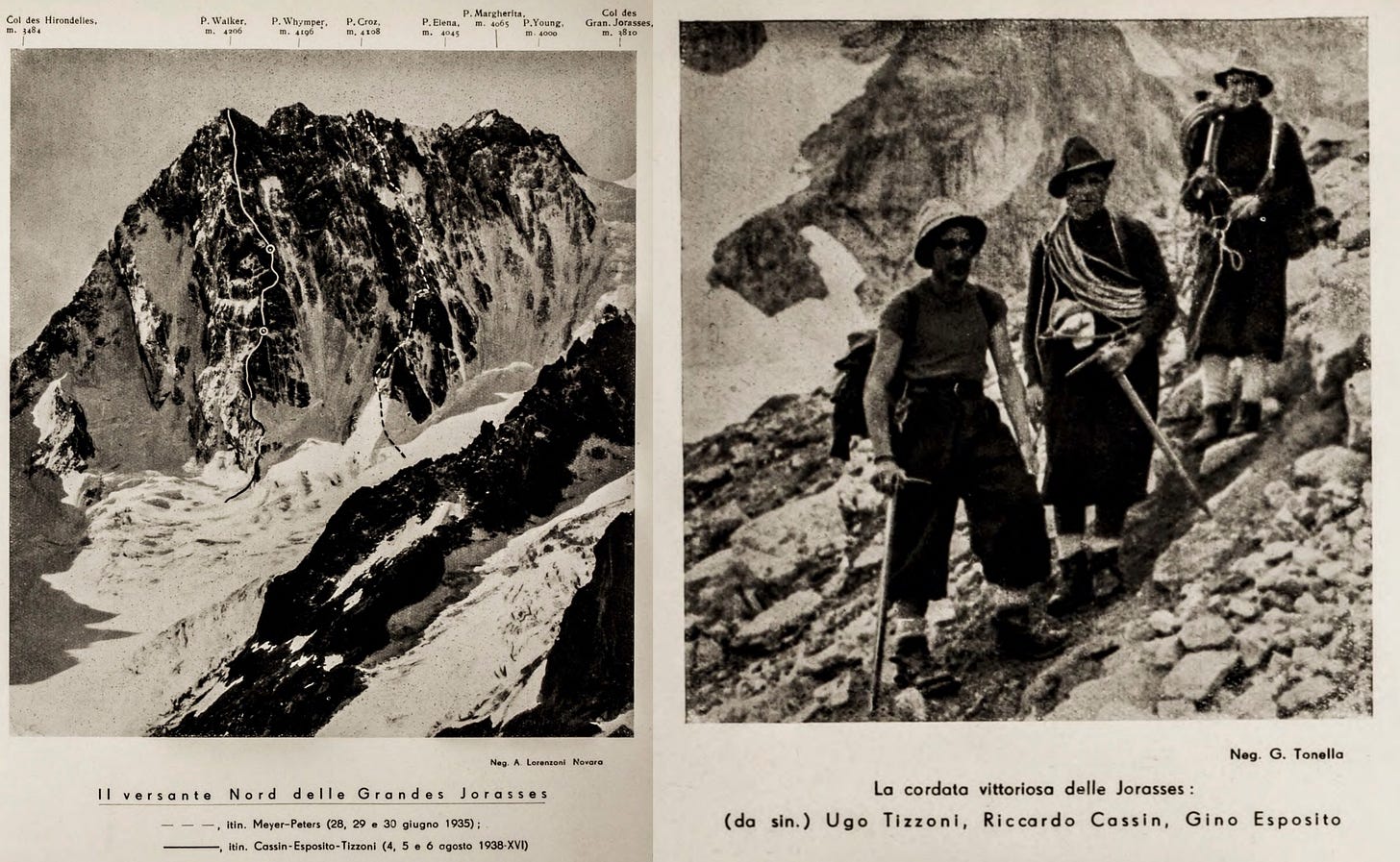

Two notable ascents in the Western Alps involving the new tools and techniques:

NW face of dell’Ailefroide (Guisto Gervasutti, Lucien Devies, 1936)

Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses (Cassin, Esposito, Tizzoni, 1938)

For some great climbing stories of the period in English, see Riccardo Cassin’s excellent history, “Italian climbing between the wars”, published in the 1972 Alpine Journal.

Mit Seil und Haken—The Eiger Hinterstoisser Traverse

We’ll finish this chapter with coverage of the 1936 Hinterstoisser traverse on the north wall of the Eiger here involving the original tension traverse techniques. Heinrich Harrer describes the rope traverse in The White Spider:

More Images:

COUNTERPOINT:

STILL TO ADD:

What we can learn from Accident reports.

More on Rita Graffer and Paula Wiesinger, and others.

more on expedition technology developments (Pierre Allain Dru ascent).

LINKS to previous writing and research:

Mizzi Langer -- first advertised rock climbing pitons (Mauerhaken)

Climbing Tools and Techniques—1908 to 1939 (Europe, PartA) Myths and Legends

Link to Google MAP useful for putting peaks in context (working copy).

Fantastic online collection of mountaineering artwork from the 1920s and 1930s

From Dave Smart: “More incredible, careful work. Thanks, I learned a lot. The point about when actually reliable carabiners were introduced is a really good one. The visual research is also very good.”. Thanks!