USA adoption of pitons 1920s-1939 Colorado (part A) Ellingwood and Lavender

Mechanical Advantage Series by John Middendorf aka Bigwall Scrapbook

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Author Note: The period between 1920-1939 in the USA was originally conceived as one chapter in my series, but now realize it will need several “parts” to research the early development of improved rope and belay systems—first in Colorado, then spreading north into Wyoming in the early 1920s, the East Coasters joining in the fun in the later 1920s, all leading to a big boom of cutting edge, world-class big rock climbs in North America in the 1930s. This part is a journey into the early technical climbs in Colorado and Wyoming in the 1920s, where the systematic use of rope and pitons began in the USA (it is also where I also learned the basics of camping and roped mountaineering). Long article—headers can be browsed for historical aspects of interest.

Early Days

The transition from mountain climbing with an occasional rope to systematically protected rock climbing in North America matured in the 1930s, but the progression took decades. It is impossible to say when the “first pitons” were used for rock climbing, as parallel developments from surveyors and miners who had been using various hardware to drill and peg rock while ascending rocky cliffs for over a century. The ascent of Lizard Head in 1920 was one of the first acknowledged use of pitons on a technical route by rock climbers. The method of its ascent became well known in the 1920s despite club reports overlooking any mention of hardware in that era.

Lizard Head, 1920

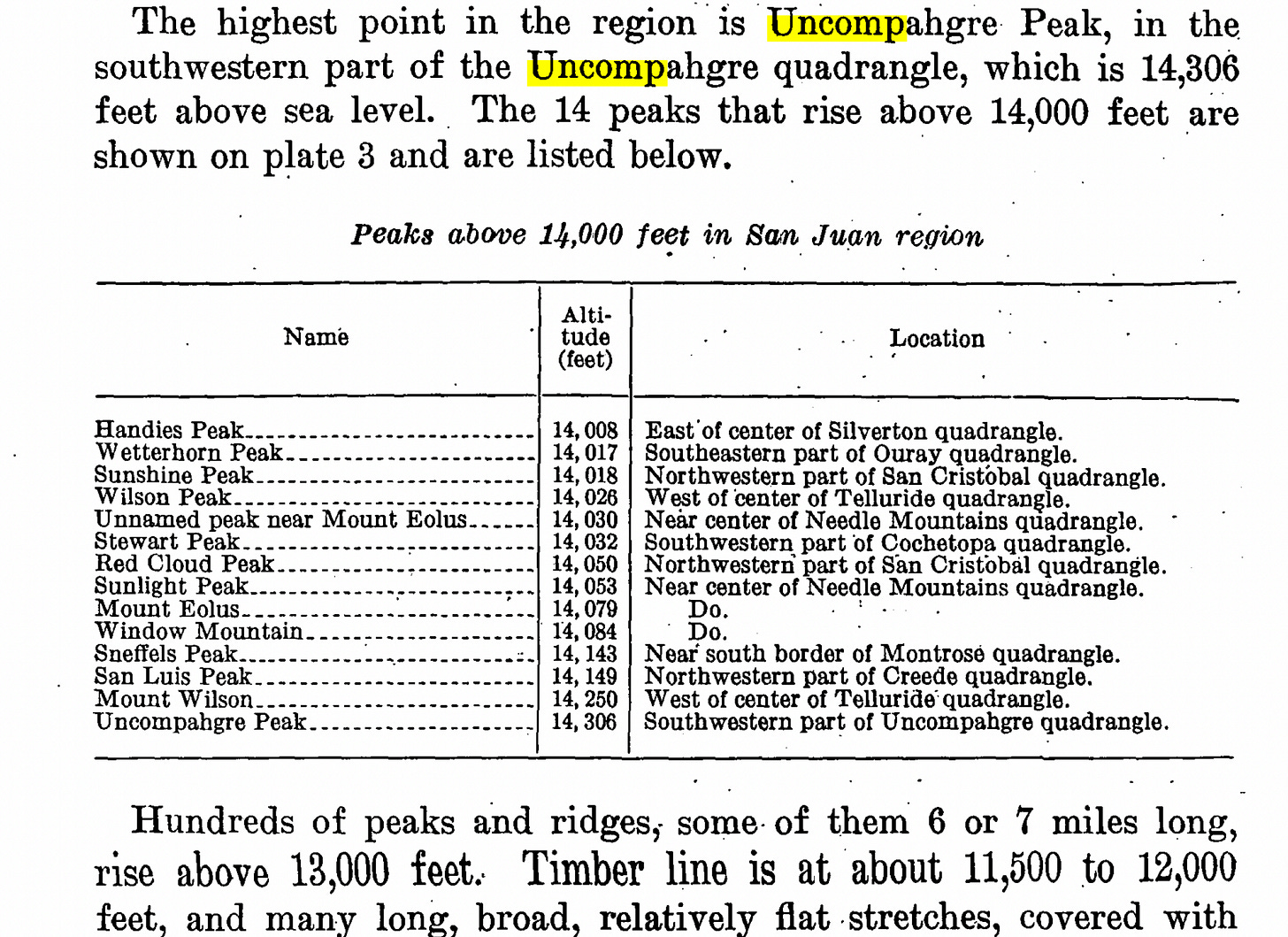

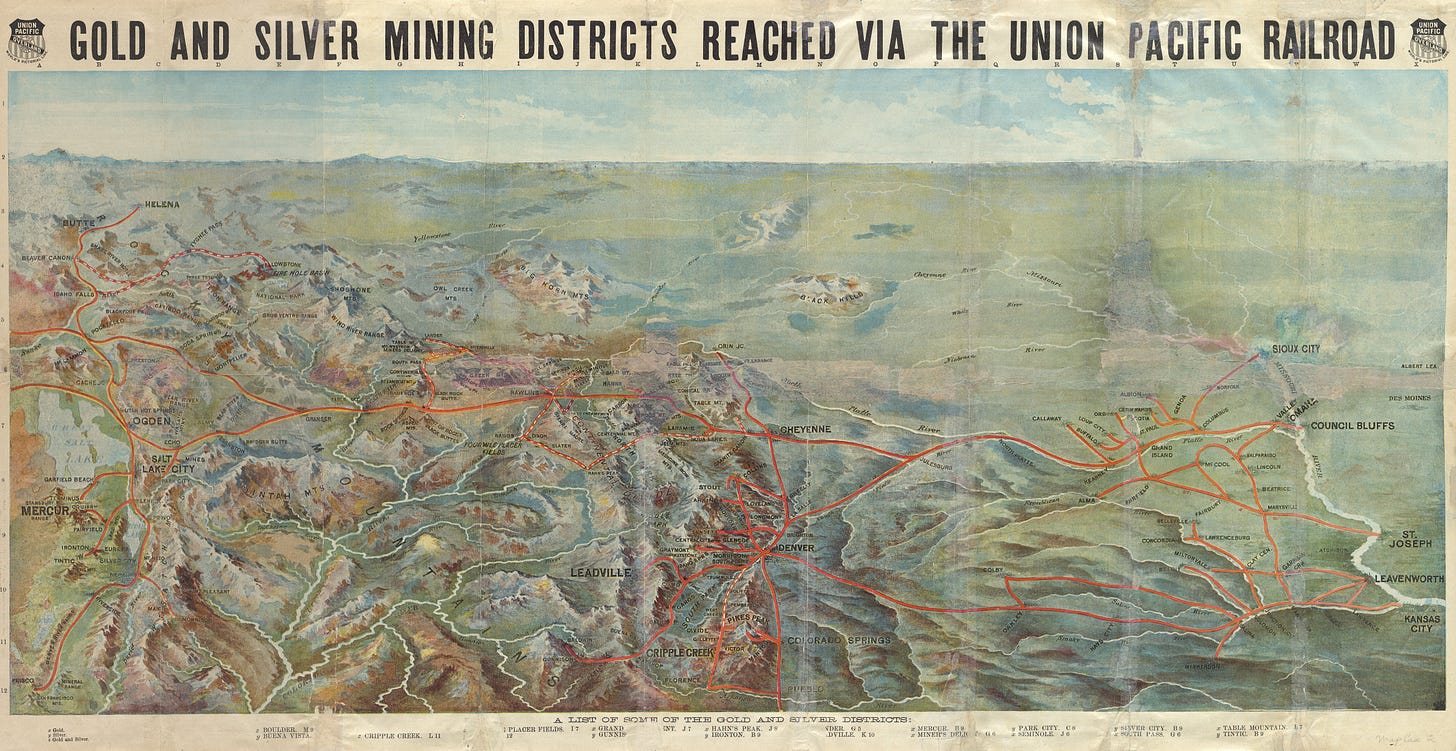

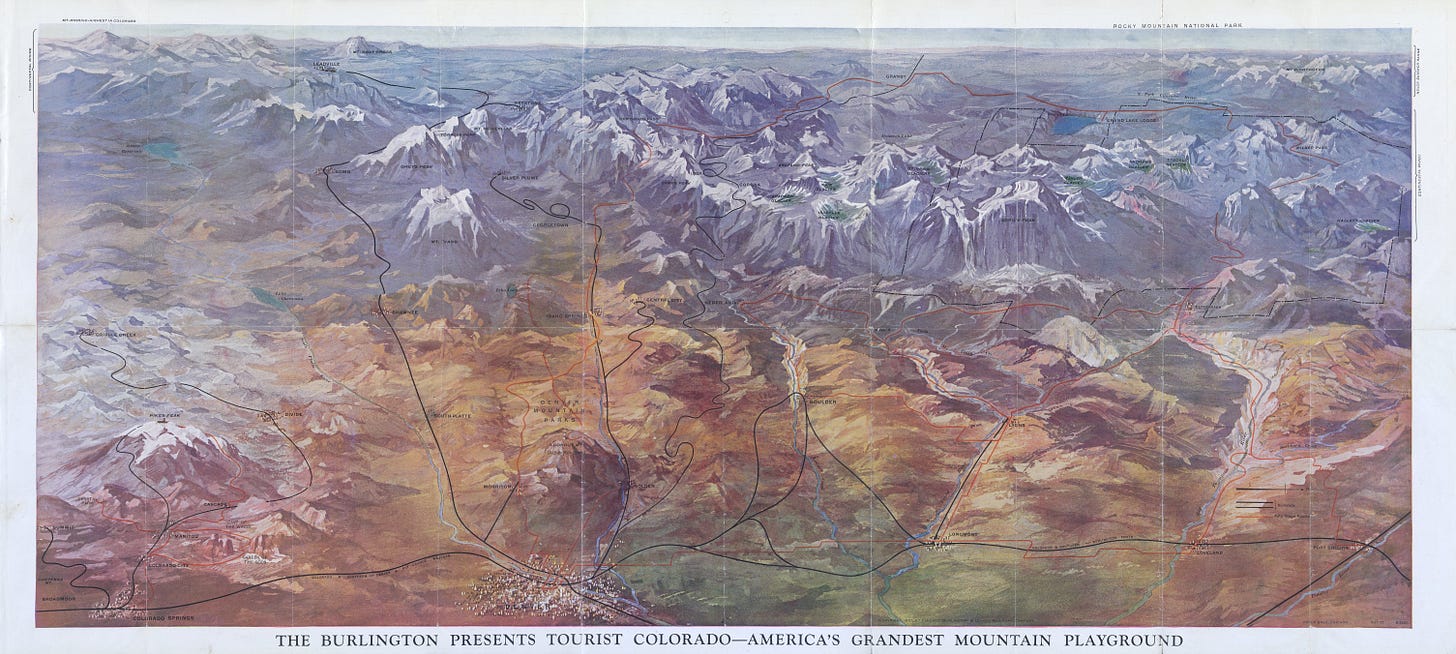

In terms of the variety of rocks to climb, America’s west is one of the most diverse in the world. After all the known tallest Colorado peaks (the “14ers”) had been climbed by 1916, climbers started eyeing the multitude of sheer stony summits in the Rockies. Many of the early forays followed obvious fault systems on steep walls and ridges of rock, sometimes involving long sections of loose and unconsolidated rock. Protection systems on these early mountainous rock-climbing routes were rudimentary; safe havens were often only the occasional “belay pin”—a lasso over a horn or spike of rock as an anchor at rope-length intervals (also known as “anchor rocks”). Using repetitive aid to ascend these routes would be folly1 (footnote), and the safest methods required bold skills in deft free-climbing, often gymnastically balancing on crumbly holds with a well-calculated distribution of weight, to overcome the most dangerous sections. Sometimes casually referred to as “third class” without a rope, or “fourth class” with rope, these sections of rock in the mountains can be dangerous and still take lives every year.

Even though the first ascent involved three points of aid, the climb of Lizard Head in 1920 remained one of the hardest routes in this regard for decades to come, later becoming known as a “fifth class” route. Lizard Head sits atop a beautiful San Juan pass in the Colorado Rockies near Telluride and was once thought to be a rocky volcanic plug, like Devil’s Tower/Bear Lodge in Wyoming, but rather is composed of a highly crumbly volcanic tuff, a remnant chunk of a 30 million-year-old ash flow. It was once a much bigger mass in the shape of a giant lizard’s head, but one night in 1911, the entire main summit comprising “millions of tons” of rock collapsed, rocking the residents of the mining town of Ophir 10km distant. Only a smaller 100m spire of rock was left standing, and when this remnant was ascended only nine years later in 1920, it began its long tenure as the most difficult Colorado summit climb2 (footnote).

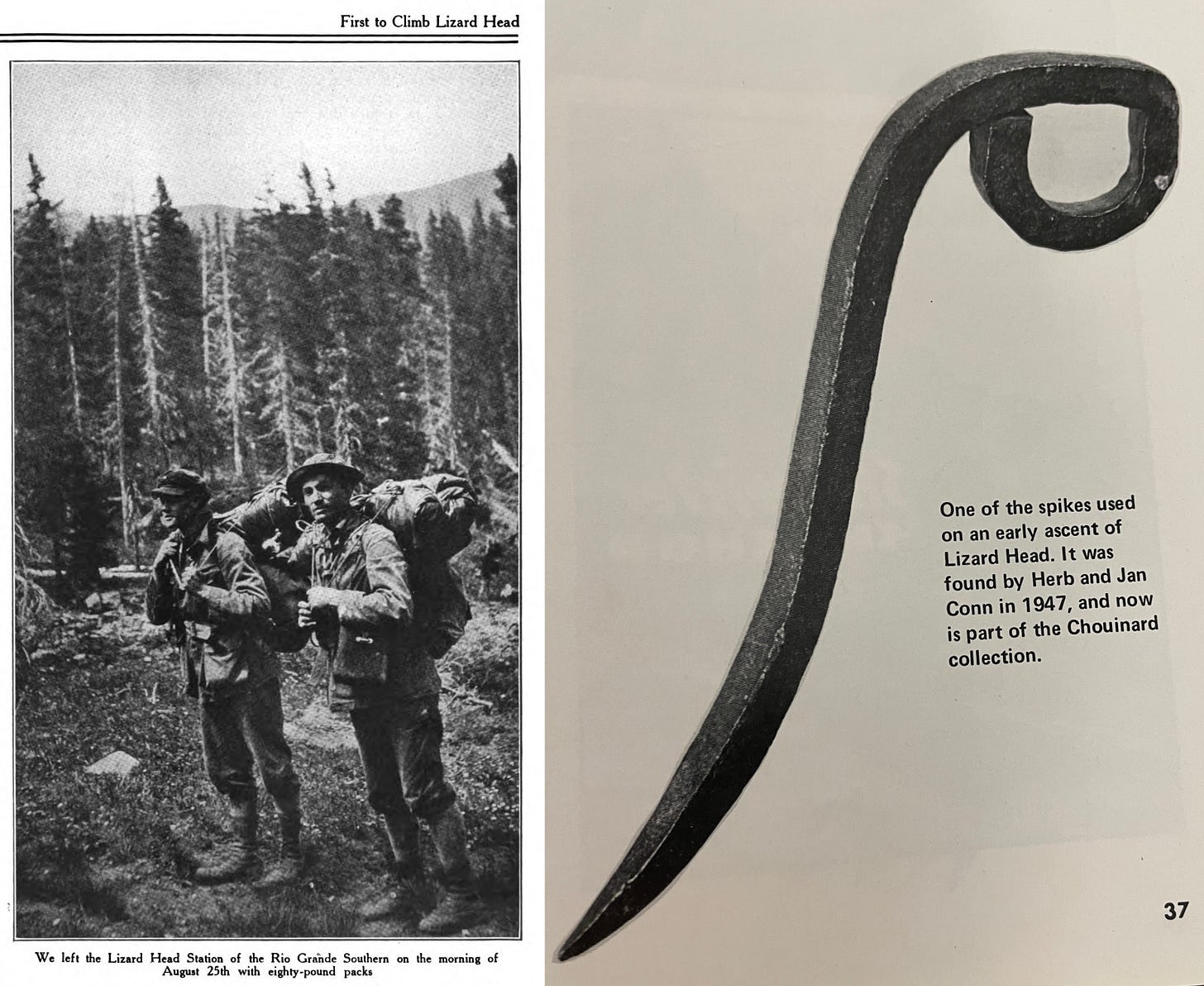

In 1921, Albert Ellingwood, who led the first ascent, published “First to Climb Lizardhead” in Outing Magazine, a popular adventure periodical of the day (1882-1923), and with a wider readership than alpine club journals. By this time, there were dozens of hiking and mountain clubs around the country publishing trip reports and other news of the mountains, and the concept of “rock climbing” as a distinct sub-sport of mountain climbing was growing. Motorized access to remote areas was ever-expanding, and as tourism also increased, the public also became more curious about the shenanigans that climbers were achieving on the wild landscapes of America.

In Outing, Ellingwood describes using pitons as “long, thick spikes, somewhat like those used for steps on telegraph poles” and indeed, he used them in the same manner while ascending Lizard Head, “driving one in the crack about waist-high to step upon”, and others as an additional hand- or foothold to overcome steep sections (i.e. not as a belay or as lead protection). They had initially planned the climb with a larger team, so luckily brought a 100-foot rope (80-foot ropes were standard for mountain climbs at the time), as safe, natural belays were few and far between and Ellingwood and Barton Hoag needed every inch of the longer rope to avert a suicide simul-climb.

Author Note: I climbed the volcanic horrorshow called Lizard Head in 1991 with Chuck Kroger; modern gear like camming devices were mostly useless in the crumbly rock, the main protection stemming up a shattered 5.8 corner were a few old dubious spikes hammered in long ago, backed up by marginal stoppers. Even though by the time of our ascent, the route had been climbed hundreds of times, still, a few hundred pounds of rocks and small boulders tumbled on our way to the summit. I was able to hide around the corner while belaying Chuck on the first pitch, but Chuck had to dodge some sizable rocks in the semi-hanging braced belay in the corner of the second pitch. Climbing this kind of rock is a mixture of ensuring one’s ability to downclimb each move, in the back of one’s mind always a plan for a potentially terrifying escape route, as more often than not, the route finding is complex and finding oneself off-route and committed on unclimbable terrain is always a possibility (as well as not injuring or killing your belayer with falling rock). These developments in the evolution of climbing in the San Juans mirror my own initial steps in climbing five decades later.

All about ropework

Prior to lightweight “artificial” anchoring technology (i.e strong steel vs. heavy wrought iron spike), climbers on these early steep rock routes were always on the lookout for sturdy “anchor rocks”, and for the leader, the rope only provided optimistic assurance for potential escape. The rope’s main purpose, therefore, was to lash onto natural flakes of rock to secure oneself and then safeguard the second, minimizing the overall risk to the team as efficiently as possible. Though Ellingwood reputably introduced rope techniques to Colorado from prior experience in England and western Europe3 (footnote) (the rudimentary techniques outlined in George Abraham’s Complete Mountaineer in 1908 recommend “paying out” the rope to the leader while anchored on a “belay pin”), it’s more probable that Colorado climbers, many who grew up learning rope and knot skills about the same time they learned to walk, became highly competent rope managers and continually evolved and improved their own unique rope, belay, and anchor systems for the steep rock climbing in the Rockies4 (footnote). There may have also been a few strong carabiners arriving from Europe and used by climbers in the early 1920s, but they would have only been a luxury to the climbers of the day, as strong ropes, lashing cords, and harness rings (strong steel rings for bridles, etc.) would have been standard equipment to facilitate safe and versatile rope management, a pre-requisite for implementing more advanced tools for lightweight alpine ascents of the wild vertical.

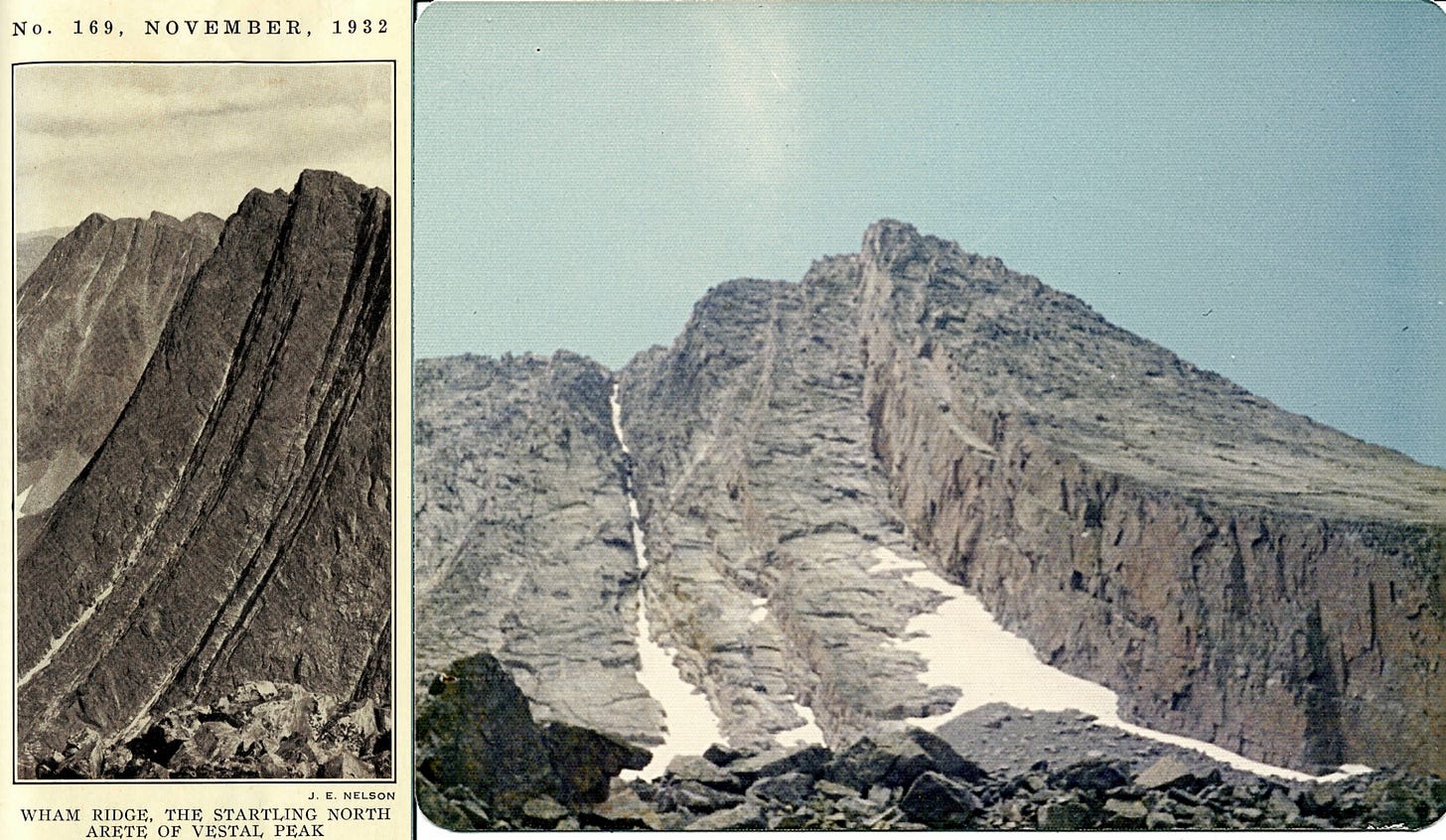

Authors note: These areas of Colorado are where I first learned ropework in 1974, at the Telluride Mountaineering School at age 14. We usually would have a stiff 120-foot Goldline nylon rope (3/8”), and sometimes also a 45m “perlon” (11mm), the European core-sheath ropes starting to become available in the USA. For some peaks (and even some of the 14ers like the Mt. Wilson to El Diente traverse), we would often bring the shorter Goldline as safety, but generally never need it as we scrambled up and down steep rock walls. We always had a good supply of shoulder-length webbing slings that could be quickly untied and tied to natural anchors, and of course, a few carabiners as well. In addition to our 14er peak bagging goals, we often carried hardware on our week-long treks in the San Juans and San Miguels, sometimes finding steep clean lines of rock on the smaller peaks, which we would climb with a very light rack of clean gear-stoppers and hexes, brought for an occasional supplement to an anchor, but more importantly insurance in case of retreat on committing climbs with unknown. Routes like Wham Ridge were basically simul-solos with an occasional proper belay. Routes, where a rope and a few bits of hardware (and an ideal weather window) were also objectives. Climbs like Lizard Head were unthinkable at our levels of experience in the 1970s, even though we were leading 5.9s and some 5.10s on Ophir Wall.

Clubs consolidate, information shared more widely…

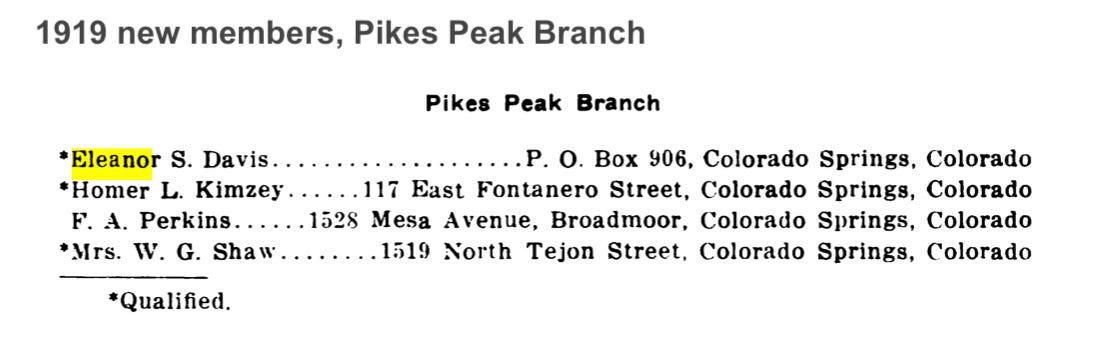

Ellingwood’s original ‘tribe’ was a group of active climbers based in Colorado Springs known as Cheyenne Mountain Club, which included Eleanor Davis, a leading mountaineer/rock climber and faculty at the prestigious Colorado College, and Manly Ormes, the librarian and father of Robert Ormes (a leading climber of the 1930s), but soon expanded when its two dozen or so members merged with the Denver-based Colorado Mountain Club (CMC) to became the Pikes Peak Branch in 1919. Initially, the Pikes Peak Branch and the main Denver branch were quite distinct groups but that was soon to change. For example, in 1920, Carl Blaurock climbed what he believed to be the “last” of the 14ers, Crestone Needle, but Ellingwood had already climbed to that summit with Eleanor Davis four years prior (Ellingwood’s first Trail and Timberline reports only appear in 1925). But after the merging of the clubs, the best of the regional climbers were to join and push new standards of long steep rock routes in America.

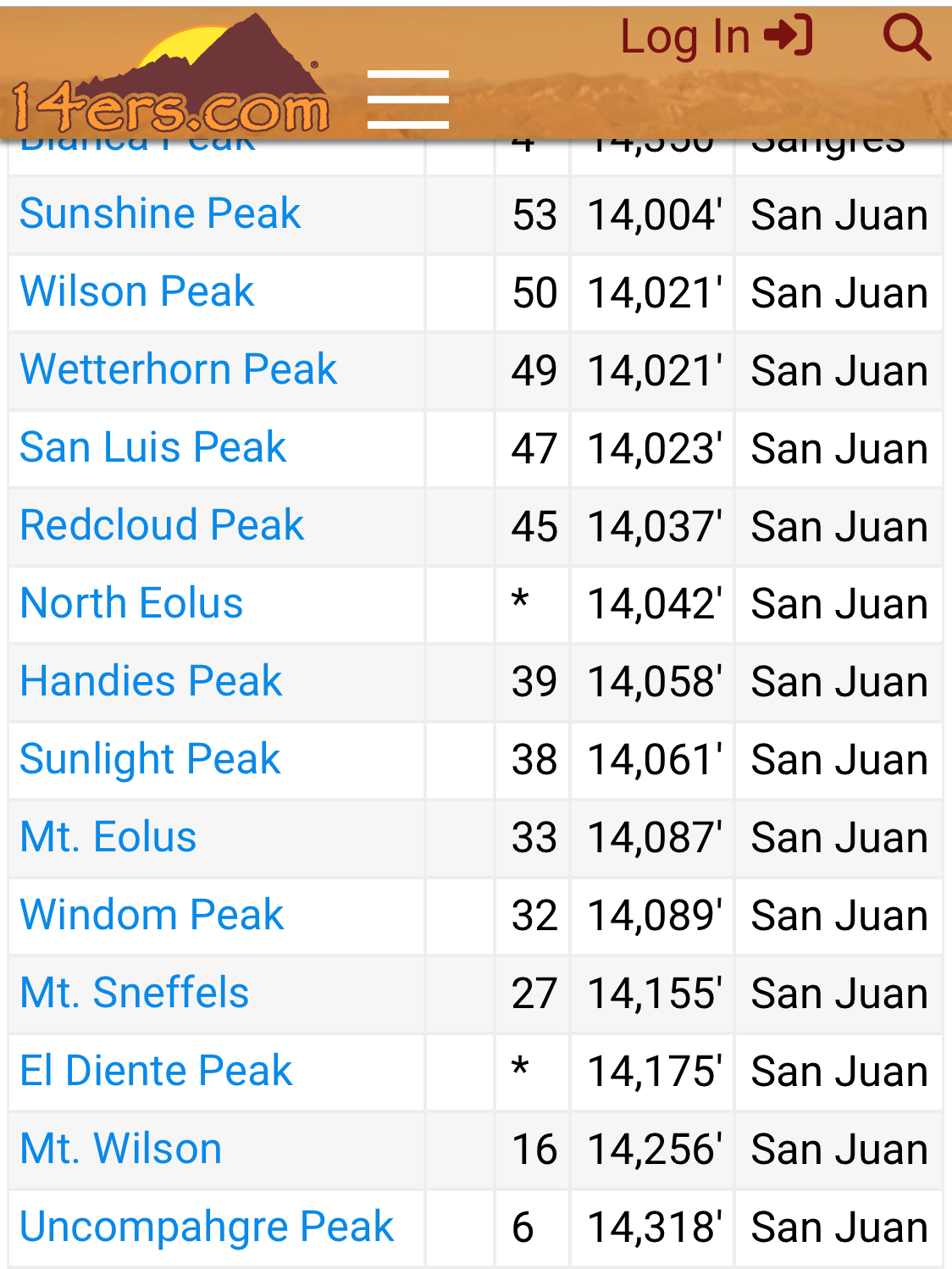

14ers (summits 14,000 feet or more above sea level)

Just as the arbitrary collection of 8000m summits became a bugaboo five decades later, summiting the 14ers became the main game afoot for the primarily Denver-based CMC members: to bag all of Colorado’s tallest peaks. In the 1920s; the list of “14er” summits was being continually refined as surveys became more accurate and climbers reached consensus on the definitions of distinct summits. For most of the Colorado 14ers, a rope is superfluous after managing any steep permanent snowfields, but several 14ers require balance climbing skills on steep rock, with a safety rope deemed prudent in places (see author note above). The journals noted news of friendly rivalries of first to complete them all, or in the shortest time, etc. —in the 1920s, many of these contenders were full-time professionals working in Denver and could only find limited time to explore Colorado’s mountain ranges. Carl Blaurock and Bill Ervin were the 14er leaders for many years, but Blaurock soon expanded his repertoire with more challenging rock climbs, often new and more difficult routes up the 14ers, and also on many spectacular lower-elevation Colorado summits.

Carl Blaurock (1894-1993)

As one of the most active mountaineering and climbing groups in the country, the volunteer-powered Colorado Mountain Club organized many camps, meetings, and lectures sharing information on access and the challenges for the many who dreamed of adventure in the sub-ranges of the Colorado Rockies. The CMC had launched in 1912 with 24 charter members and by 1918 had 435 dues-paying members (including Carl Blaurock), expanding to over a thousand by 1922. In April 1918 they began publishing Trail and Timberline as a “monthly bulletin to contain reports of events past, announcement of events to come, and such other material that may suggest itself from time to time.” Blaurock and his family Irma and Ottilie were active members and contributors, leading camps (both summer and winter), participating in theatric events, and serving as a director beginning in 1921. Camps generally began with large groups heading into the mountains for up to a few weeks, with smaller teams of half-dozen or so alpinists splitting off for the big goals, routes often requiring coordinated ropework on fourth-class summits. Blaurock was a respected leader and led many first-timers to high summits, and his endurance treks were legendary: one trip with Dudley Smith, Bill Ervin, and Bob Nelson in the San Juans linked multiple ranges involving 60,000’ of vertical gain over 200 miles, while “galloping” over a dozen 14ers. It was one of many successful trips (other early notable rock climbing mountaineers include Agnes Vaille, Elwyn Arps, Henry Buchtel, Steve and Jerry Hart, William and Clyde Smedley to name a few). Blaurock was a natural on steep rock and was noted in the journal as having “good sense in his acrobatic performance.”

Hermann Buhl (1891-1931)

Hermann Buhl, was born in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, and migrated to the USA in 1913, first as a student at the University of Chicago, then moving to Denver in 1917 to begin a career as an investment banker. Before he migrated at age 22, Buhl had climbed in the Swiss Alps, and in the northern limestone Alps, home to the Zugspitze and the Kaisergebirge and famous climbs like Tita Piaz’s 1908 ascent of the west wall of the Totenkirchl. There are no mentions of Hermann Buhl in the German-Austrian alpine journals prior to 1913, but there are hints by people who knew and climbed with him that he had repeated several difficult piton-protected rock climbs prior to his becoming an American. Bob Godfrey writes in Climb!:

“Buhl had climbed frequently in the European Alps and was a member of the Swiss Alpine Club prior to his emigration to the USA after WWI. He was familiar with the use of modern climbing equipment, including pitons, crampons, carabiners, and ice axes, as well as with the technique of rappelling and the use of rope for protection against a fall.” (Climb!, Bob Godfrey and Dudley Chelton, 1977).

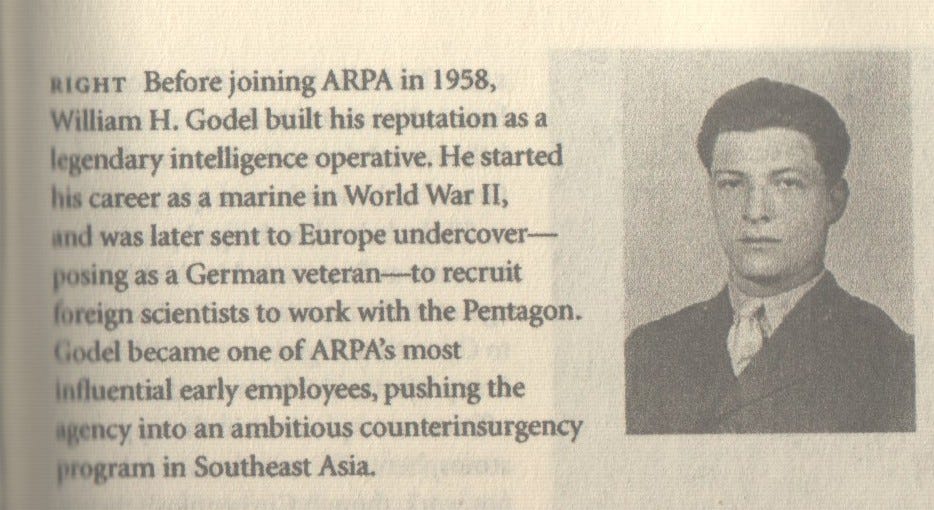

Buhl joined the CMC as a “qualified member” in 1919, and quickly became active in organizing winter trips and writing articles for Trail and Timberline (he was also a world-class skier and ski instructor, teaching contemporary European techniques during Colorado's early ski evolution). He married Lumena Wortman in 1920, and she also became a CMC member and an accomplished climber (their son William Godel became an international spy and deputy director for DARPA). Buhl sadly died of pneumonia after leading a winter camp in 19315 (footnote), but in those twelve years with the CMC, he was a well-respected, accomplished rock climber and a valued member of teams pushing new limits of rock climbing in Colorado and Wyoming.

Daredevils and rock climbers.

In the 1920s, American daredevils were capturing worldwide fame, enhanced by images in newspapers and magazines, photography oft made possible by the latest clever and portable folding cameras: "human flys" climbing tall buildings, wire walkers like Ivy Baldwin and the Wallendas performing high wire acts, barnstormers dangling from speeding airplanes, untethered construction workers defying gravity, high-divers and pole-sitters seeking records in scenic locales. Many of these “daredevil” feats involved climbing skills. The major climbing clubs and organizations—the Mountaineers and Mazamas in the northwest, the Sierra Club in the west, and the American Alpine Club and the Appalachian Mountain Club in the east—were primarily interested in big mountain climbing and exploration, which involve more expeditionary expertise rather than climbing skills. Steep rock climbs were still considered more the realm of daredevils than of proper mountain climbers6 (footnote).

One of the more elite yet discreet “daredevil” games (where participants sought only peer celebrity) was the art of building climbing on university campuses, which were often full of climbable Gothic architecture, a popular collegiate design style to create an atmosphere of respected antiquity. In the spirit of the Night Climbers of Cambridge, James Alexander likely gained his skills in the art of ropeless balance climbing on the buildings of Princeton University in New Jersey, where he was first a student, then as a professor at the Institute of Advanced Studies (where he was a peer of Albert Einstein).

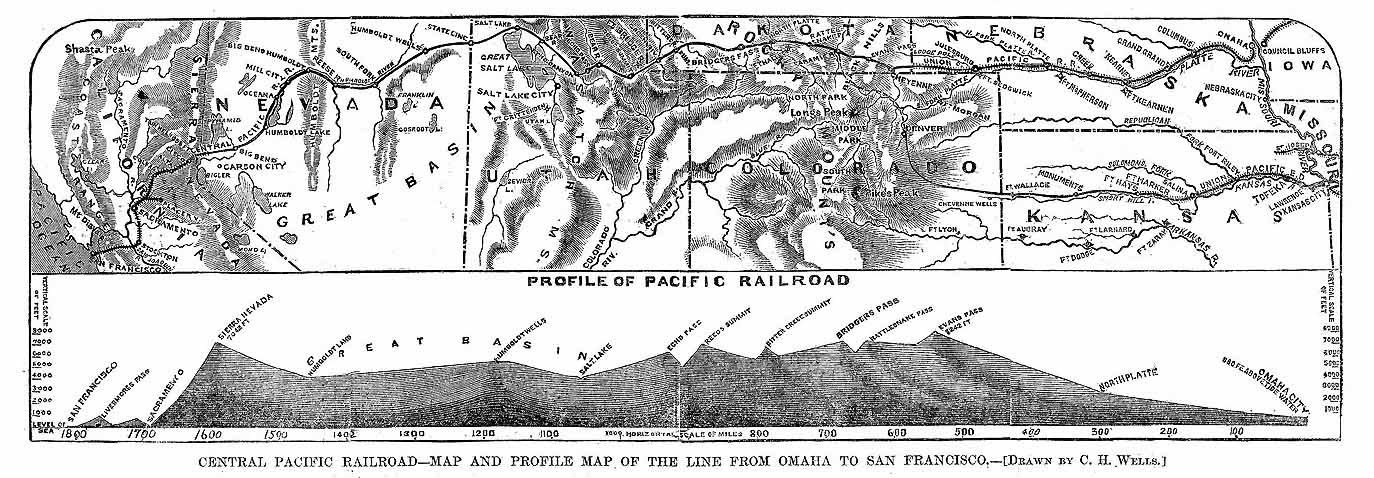

Long’s Peak, 1922

In 1922, Alexander climbed a 200m steep rock face on the east side of Long’s Peak in basketball shoes, ropeless and using only an ice axe used to chop steps to the base, then continued to the summit. The route later became known as Alexander’s Chimney; it was his first long “rock climb”, and perhaps the hardest free climb in North America at the time (though no doubt less acrobatic than some of the building climbs at Princeton). Alexander returned a few days later and climbed it again with resident ranger Jack Moomaw, who wrote a harrowing tale of the experience.

In 1922, Blaurock published in Trail and Timberline, “A Trip Up the Northeast Face of Long’s Peak”, documenting the Colorado Mountain Club’s ascent of the route only a few days later, with a large team of seven climbers and only a single 70-foot rope (21m) which had to be passed between groups. Hermann Buhl did most of the leading while the others often used tension from the rope to overcome the steep bits. Buhl’s wife Lumina and her brother Herbert were also part of the team. It’s here we can see the lights coming on—instead of the typical team of half dozen or more climbers to storm summits, Blaurock concludes that three people would be an ideal size for such climbs. It was here also that Buhl demonstrated the European custom of switching to lightweight rope-soled shoes for rock climbs (Blaurock also brought a pair and led some steep sections), rather than the heavy boots with Swiss edging nails considered standard at the time. It’s unlikely they had any pitons to safeguard the route, but in reading the report (e.g. “Found Buhl sitting on ice with his feet braced against two small projections on the side of the chimney”), it’s clear that the security of an artificial anchor, of the lighter steel kind familiar to Buhl but not yet established in Colorado, would have been welcome.

It was in this period that the concept of a piton as a spike for an extra foothold or handhold transitioned into an anchoring safety device and as a potential tool for a retreat for the more daring climbs, though on Alexander’s Chimney, the commitment was not extreme, as retreat down its ledgey corner system would involve belayed and sometimes easier ropeless downclimbing, with several manageable rappels off natural anchors. Yet an artificial tool as an emergency anchor on committing routes would have started looking attractive to many early rock climbers if it was well designed, relatively lightweight, and fit for purpose. Longer ropes for climbs of this caliber was also noted as critical, as it provides more options for safe travel (70’ was too short!, they discovered on Longs).

Later in the decade, Alexander’s Chimney became a popular climbing route, recommended to those who enjoy “unusual and difficult ways of ascending mountains”, fueling further interest in spires and steep summits previously considered “impossible”, a term very much in the vocabulary of climbers of the time.

Commitment increases

In 1923, Ellingwood repeated the Owens Spalding route on the Grand Teton with Eleanor Davis, who led rock climbing sections in "sneakers", further opening the Coloradoan eyes to what was possible. Ellingwood, Blaurock, Buhl, and others continued to climb new technical routes in Colorado and Wyoming; many were bold forays up elegant new lines on long rock routes, managed with coordinated ropework by the team.

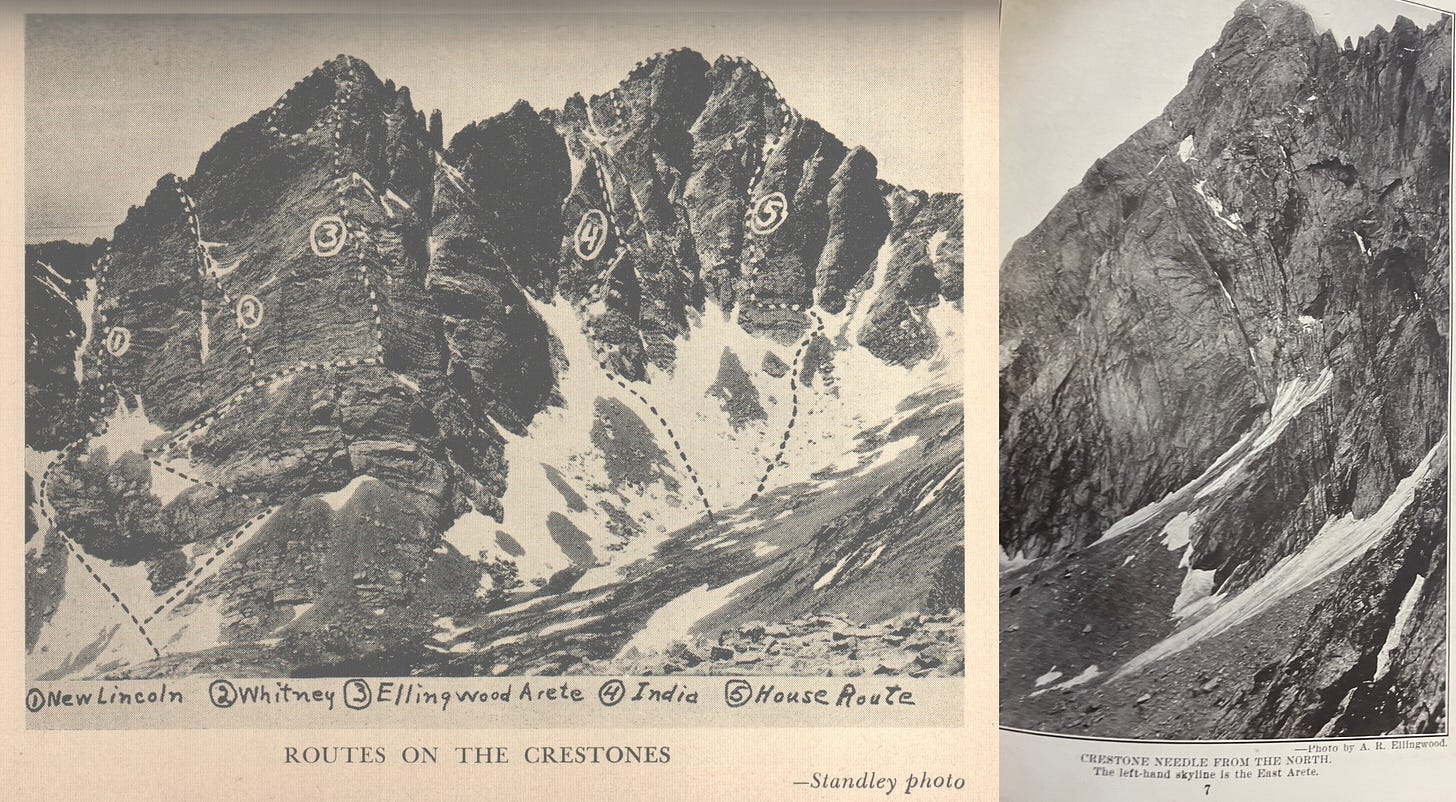

Crestone Needle, 1925

The Ellingwood Arete on Crestone Needle, climbed in 1925, is a visionary line involving acrobatic and exposed free climbing (then called “fine balance technique”), where a fall was not an option, but the lead made more palatable with the ability to rope off a natural belay pin, sometimes called a “hitch”. Ellingwood describes starting up the Eastern Arete of the Crestone Needle with Eleanor Davis, Marion Warner, and Stephen Hart in 1925:

“There were pessimistic doubts expressed as to the last five hundred feet, where the precipice seemed to attain verticality, and near the top of which a huge boss of well polished rock was certain to force us into an enormous overhang from which we could discern no avenue of escape. But we set forth.”

Ellingwood notes that the team used (natural) anchors that could “hold a thousand pounds”, but notes that some belays involved precarious stances and careful maneuvering of the team, sometimes requiring members to brace in precarious positions while the rope was used elsewhere. Committing routes of this caliber boomed in the 1920s, and it is easy to imagine how carrying a piton or two would have lessened the fear when heading into more dangerous unknown territory, where sudden storms were also a possibility.

“Fine balance climbing” (free climbing) was more widely practiced on the more accessible cliffs by the rock climbers of the day7 (footnote)— it’s unclear what local experimentation with artificial anchors as safety in the early 1920s, though it would be typical for climbers to practice new methods on local crags prior to lugging any extra gear into the mountains.

Wind Rivers

In the 1920s, access to the Wind Rivers in Wyoming was improving8, and climbers started pouring into this wild and scenic range. In 1920, Arthur Tate writes in Appalachia: “Fremont Peak, 13, 720 feet, was ascended in 1842 by John C. Frémont the great explorer but practically all the other prominent peaks are unclimbed, including Gannett Peak, 13,875 feet, the highest peak in the range.” Tate climbed Gannett two years later and published his reports in Appalachia, noting the pleasant camping conditions:

“There are superb wild flowers everywhere and much wild life, including the mountain sheep, many elk, moose and bear. Certain of the streams afford excellent fishing—trout and grayling. The higher regions are truly alpine, with rugged peaks, extensive glaciers, many waterfalls and an extraordinary number of mountain lakes.”

Something for everyone, in other words. To the rock climbers, new “impossible” climbs became more visible on the high-quality granite batholiths, on rock more solid than the crushed uplift of other Rockies ranges. In the 1920s, the Wind River range (the “Winds”) became a prime “destination” for climbers, with updates of climbs in the range published internationally. In 1924, Ellingwood, Carl Blaurock, Hermann and Lumena Buhl spent ten days reconnoitering trip in the northern Winds, climbing several new routes, and noting, “excellent rock for climbing (as is true for the whole region)”. Here we see more prompts for better systems to more efficiently reach summits, by climbing the steep rock buttresses rather than the obvious lines of weakness in the snow and ice gulleys. On the north wall of Freemont, while the Buhls and Blaurock were chopping over 100 steps in an ice gulley to the side, Ellingwood “tackled the rocks of the pinnacle directly. Tried three different routes and got hung up the last time on an eight foot ledge which for perhaps 15 minutes I could neither make it up or down.” Shortly after, the rest of the team reached the ridge above and started back to assist with a rope rescue, but Ellingwood was able to downclimb “the ticklish crack I had ascended” and found a feasible line to the top, recommending it as “easier and quicker” than the ice route, and continued taking direct rock climbing lines to the summit rather than ducking into the more enclosed ice chimneys off to the sides.

Ellingwood marks this time as the start of “a new chapter” in the history of mountaineering, and the first ascents in the Winds “set the ball rolling”. In the years that followed, routes up the steep rock walls in the Winds were being eyed with a more expansive view of the “possible”, new tools and techniques were adopted, and by the end of the 1920s, climbers were ascending new routes in the Winds fully equipped with pitons, carabiners, and safer running belays for bold and difficult rock climbing.

Tetons

At the same time the limits of possibilities were being explored in the Wind Rivers, interest in the more alpine challenges of the Tetons was also on the rise. Just as the east wall on Long’s Peak was later first ascended by a daring soloist, in 1919 LeRoy Jeffers climbed the “unclimbable” Mt. Moran, bold solo up the northeast ridge followed by an epic nighttime descent. The climb became national news9. And just as on Longs, subsequent teams soon repeated the routes with safer techniques involving ropes and equipment, including an ascent by Ellingwood and Blaurock on their way back from the Winds.

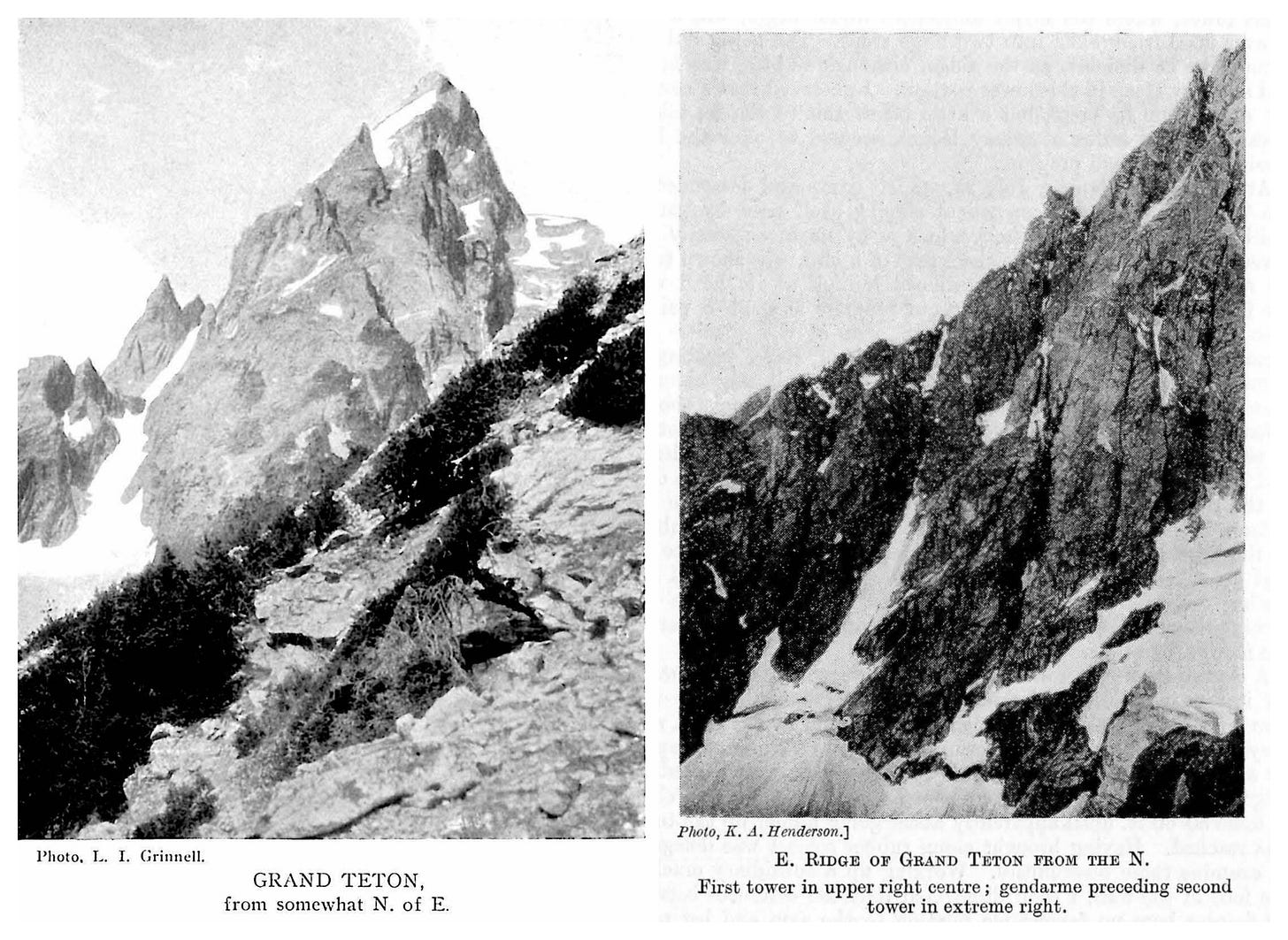

The more obvious and direct routes to the summits which involved steep rock climbing increased in appeal. Ellingwood lays down the challenges of new routes on the Grand Teton in “The Call of the Rockies” in Appalachia in 1926: “It will take master at rock work to find a new route on the big west wall above the upper saddle, to ascend the north ridge to the lofty summit, or to overcome the cliffs and gendarmes on the southeast arete.” And indeed in the years that followed, these routes and others would all be climbed with “special technique” to summits that thwarted initial mountaineering attempts.

Prior to the ascent of the last unclimbed Teton, Mt. Owen, in 1930 by Teton locals Fritiof Fyxell & Phil Smith, and East Coasters Robert Underhill & Kenneth Henderson (more on the East Coast climbers next), the East Coast climbers had climbed the East Ridge of the Grand Teton in 1929—a 4000-foot rock climb and landmark route now rated 5.7 with a recommended rack of a dozen cams and nuts. No mention of pitons is reported in their published account of the climb, even though the authors had been noting the benefits and use of pitons for several years. It is Fryxell who first describes the use of pitons10 in the Tetons in the 1932 American Alpine Journal, of his 1931 ascent with Underhill of the North Ridge of the Grand Teton, where the pitons were used for aid, a technique which soon became known as “tension climbing”. This is very unlikely the first use of pitons in Colorado and Wyoming, but an important acknowledgment as the direct aid of pitons was integral to their ascent, important information for others who dreamed of repeating the route. The use of these aid pitons was noted as "justified" in the journal.

“Special Technique”

Many stories have been written of historic climbs as being first done without pitons, which, to a modern climber, infers they were essentially dragging a rope and soloing exposed, tricky, possibly icy 5.7 or 5.8 climbing with death fall potential. If the reference to artificial anchors was not reported, then some readers have assumed that no pitons were used. Not so: there are examples where a 1920s climb is described in minute detail, but with no reference to safety anchors which in later years were reported or known. The assumption of having a few safety pitons for certain climbs was recognized by the cognoscenti, the relatively small group of climbers within each of the national centers who were focused on steep rock balance climbing (very bold solo climbing on the Sierra granite peaks was also developing at a fast pace, e.g. Normal Clyde). When it came to tension (aid) climbing techniques being developed and practiced in the 1930s, only then did it become the norm to count the pitons and provide a “rack” of equipment needed to repeat the climb. But there is no doubt that during the explosion of new rock climbs in the Rockies between 1925-1930, pitons had been used for anchors and for “roping down” the new testpieces of the day, many of which have faded to obscurity.

In “Technical Climbing in the Mountains of Colorado and Wyoming”, Ellingwood’s debut article in the prestigious American Alpine Journal’s second issue (1930), he provides a list of technical climbs requiring “special technique”, among them Lizard Head, new routes in the San Juan Needle Mountains, ascents in the Wind Rivers and “new and interesting routes” in the Tetons, including “several of the lower pinnacles.” He makes no mention of any hardware, but the implied use of pitons for roping down becomes clearer on more technical backcountry climbs in the San Juans climbed in the later 1920s11. Ellingwood also warns those not familiar with the new tools and techniques about embarking on the new wave of climbs: “Of course, climbers in the Finch school, who dismiss all rock-work as nothing but acrobatics, will be disappointed.” (footnote on Finch TK).

“Special technique” in reference to both rock climbing skills and equipment appears elsewhere in early journals, the term presumably substituted so as not to ruffle feathers of senior mountaineers not interested in such climbs and who considered protected lead climbing technique with artificial anchors as a bane to the spirit of climbing (but on the whole, US writers expressed less pious opposition than the British old guard). In his article “Reflections on Guideless Climbing” (1930 AAJ), Noel Odell infers the specialized technique goes well beyond the “ultra-gymnastic” ability of the participants Indeed, the ability of anyone to create a secure anchor in precarious places absent of any natural belay pins was perhaps the most significant driver of guideless climbing, as fewer climbers required the services of a guide to keep them safe on the wild vertical12 (footnote).

Enter the designers

To recap, we’ve looked at some of the new standards of rock climbs of the 1920s where a solid anchor placed in a crack would have made the climb more possible, efficient, and less nerve-wracking. We know the climbers of the day were familiar with pitons, and how they helped make famous climbs like Lizard Head possible. And we can conjecture that undocumented pitons were appearing on the more technical climbs in this period from both inferred and explicit primary resources. What was not yet fully developed in the mid-1920s was a versatile standard tool that was light enough to be carried long distances into the mountains and on steep routes, provide trustworthy security, and most importantly, be available to climbers. Enter the designers.

Although there was some filtering of efficient hardware and rope systems from Eastern Europe to Colorado and Wyoming, information flow was probably very limited until the borders of the former axis countries became more fluid in the mid-1920s. Buhl had migrated from Germany in 1913, a time when pitons were becoming common in his climbing areas, but of varied designs and probably still few of the proven Feichtl designs (see Piton Evolution, part 5). In the later 1920s, more East Coast climbers were traveling and climbing piton-protected testpieces in the Eastern Alps, and there was increased migration to America adding to the knowledge base, but in the meantime, Americans started making their own hardware designs.

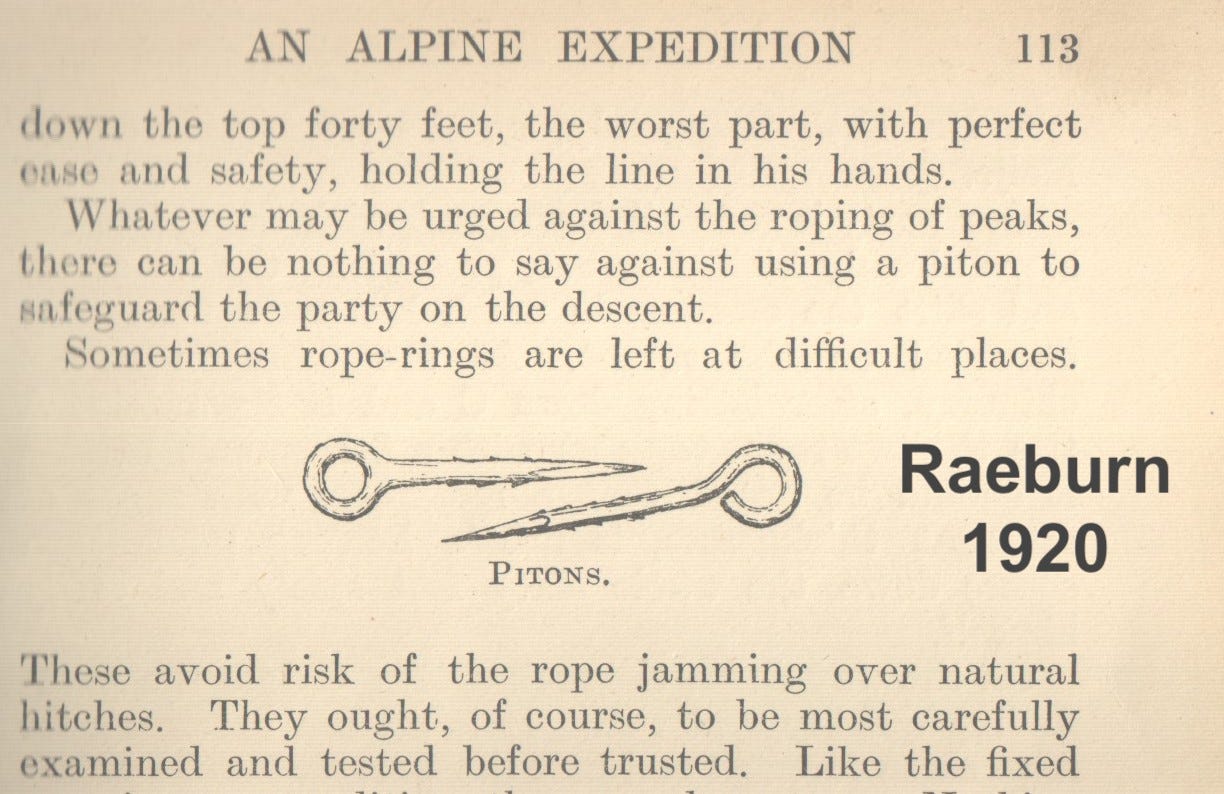

The first American piton designs were no doubt informed from a British climbing instructional, Mountaineering Art, by Harold Raeburn (1920), a more compact textbook than the rambling tombs published by Abraham (1908) and Young (1920). Although Young was the first to publish on the need for an “indirect belay” to help absorb forces in a lead fall, Raeburn’s text is arguably a more clear and direct explanation of techniques becoming more universal at the time, including specific details on the design and use of pitons (whereas Young devotes four pages to dismiss “pegs” as rarely justifiable). Raeburn’s book was sold widely in America and was reviewed by LeRoy Jeffers in 1921 Appalachia, who noted it as “an interesting and valuable addition to the library of any climber.” As Raeburn notes, pitons were acceptable for “roping down”, yet of course would also be useful to create a belay in places optimal for safety (i.e., before difficult sections).

In the 1920s, the USA led the world in steel products, and climbers benefited from higher-grade heat-treatable steels more readily available to small-scale crafters (in Europe, pitons were mostly mass-produced by this time from a low-carbon “soft” steel). The simple rolled-eye design shown below, made from round stock was likely the most common design in the 1920s. As pitons were initially only accepted for “roping down”, they were integrated with forged or welded steel rings to enable easier pulling of the doubled rope—the rings were commonly available and designed to withstand high loads of a pulling harness for horses (1.25” horse harness rings were recommended for pitons). The idea of using a forge punch to create a stronger closed eye was not yet standard practice in the USA (next chapter). It’s unknown when climbing hammers were adopted, though a hammer of some sort would have been a carried tool on horse-pack trips into the backcountry (say, into the Winds) to install tent structures and other needs.

“Unlimited possibilities”

One could say the first “open source” climbing hardware designers in the United States were Dwight Lavender, who, along with Melvin Griffiths, published a series of articles in Trail and Timberline specifying materials and design of Colorado’s state-of-the-art tools for the vertical. Whereas in most circles, climbers who were starting to use pitons on the harder rock climbs were discreet about their use, Lavender was straightforward about the need for hardware13. In The San Juan Mountaineers’ Climber’s Guide to Southwestern Colorado (1933), perhaps the first guidebook in North America to recommend the new tools, Dwight Lavender writes, “There have been several climbs made that require the use of pitons and karabiners, and there are unlimited possibilities for many more ascents as difficult.”

Dwight Lavender (1911-1934)

Dwight Lavender was born in Telluride, Colorado, the heart of the San Juans, and during his teenage summers, along with his older brother David, spent most of their time in the backcountry, climbing and becoming the oracles of Southwest Colorado mountaineering. In 1929, Dwight began his freshman year studying Geology at Stanford University in California but returned to Telluride every summer to climb with his friends in the San Juan Mountaineers, a sub-group of the Colorado Mountain Club based in Telluride and Montrose. Sadly, he died from the polio virus at the young age of 23 during his final year of study at Stanford.

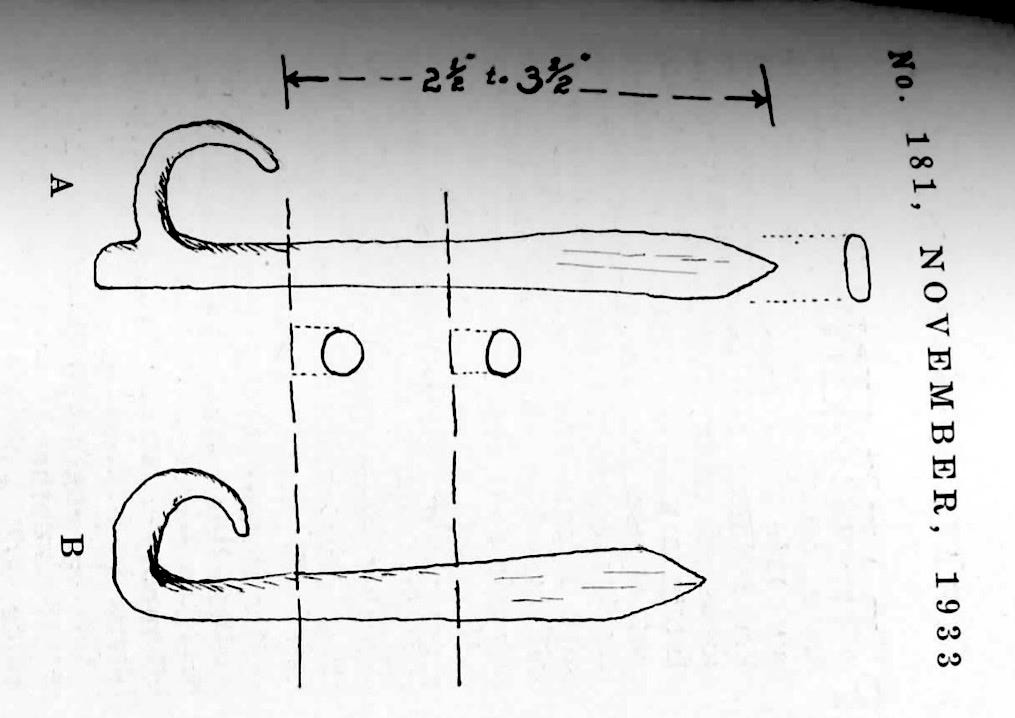

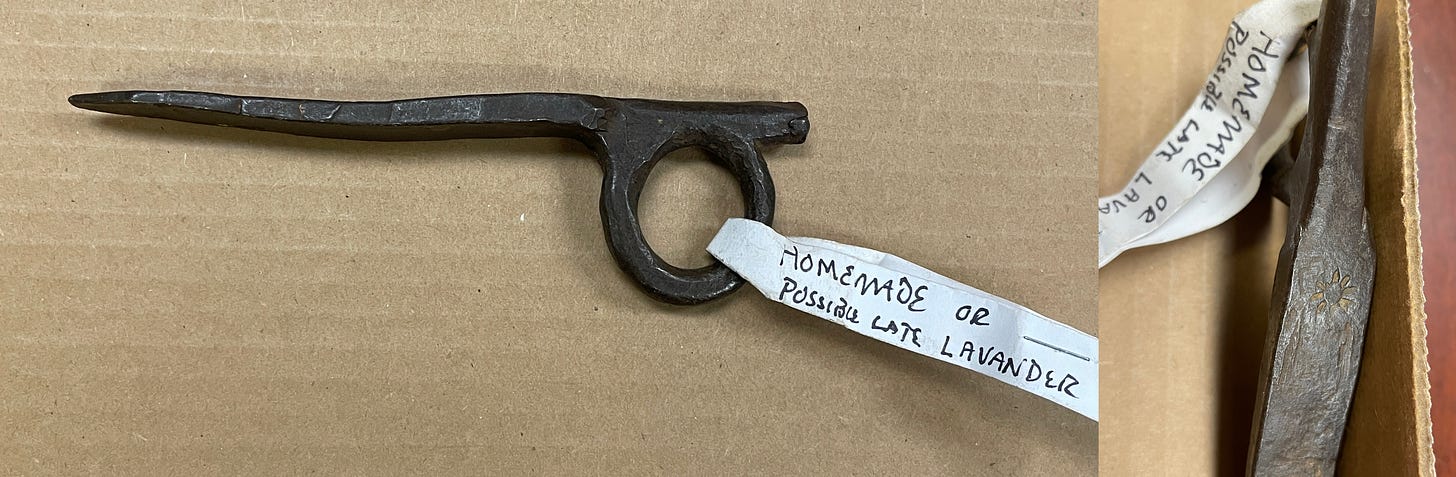

At the Stanford student foundry14, Lavender created a new piton design, which he called the “San Juan Piton”. His initial designs were "great big things", made from one-inch steel and eight inches long, but he soon improved on the “older style” pitons by the addition of hitting surface extension to provide a more directed impact when hammered into cracks. Contrary to popular lore, the closable eye was not to capture a lead rope but more to provide the versatility of adding a "rope-off ring (1 1/4 inch harness rings)", when the piton was used as a rappel anchor. It is also possible that the piton could be placed “eye-up” to act like the original “Mauerhaken” piton design, acting as a hook for the rope to be draped over, though slings and carabiners had become standard equipment by this time.

Over the years, Lavender improved its design, creating a versatile lightweight design. Early pitons were generally long and made with thick round or square shafts; Lavender designs recognize the need for a flattened blade for thinner cracks (both horizontal and vertical—see caption below). Regarding length, he writes in Trail and Timberline (Nov. 1933): “It is seldom possible to drive a five or six-inch piton in its full length. A two-inch piton in all the way is better than a six-inch piton in half way.” Modern USA-made pitons were beginning to take shape.

Lavender and Griffiths also designed new framed backpack designs, and other equipment to make backcountry trips more efficient and lightweight. Lavender was a proponent of 120-foot-long linen yacht ropes as opposed to the Italian hemp and manila, which “have been the standby for years” (1933). He notes the linen ropes were “a soft rope, easy to tie and handle, much less apt to cut on sharp rocks than wither manila or Italian hemp, and certainly more pleasant on the hands.”

Roping Down

The San Juan Mountaineers were not just developing new tools, but also sharing new techniques in their “Notes on Equipment” articles. In Lavender’s photo albums, he documents various body wrap abseil methods. The original Dülfer method involved wrapping the rope around the neck to gain additional friction (left picture below). Lavender describes the “correct position for roping down” with the rope under the arm (right picture below), a much smoother method for pure descent, and indeed, became the standard body rappel method in America for the next four decades (Dülfer’s around-the-neck method was better for controlled tension traversing—see the myth of the Dulfersitz).

Mount Sneffels

By the early 1930s, climbers nationally were starting to establish bold piton-protected climbs (next chapter), and the direct north face of Mount Sneffels, a high-altitude 14er, was one of the most committing and difficult climbs of the era, first ascended by Lavender with Gordon Williams and Mel Griffiths in 1932. Dwight’s brother David later writes, “Dwight and his hulking two-hundred-pound side-kick Melvin Griffiths, discovered the choice mountaineering possibilities of Blaine Basin in the western San Juans, between Telluride and Ouray.” In the shadow of the stupendous north face of Mount Sneffels, they “became so enamored of the spot that with incredible toil they packed up to timber line on their backs enough material to build a shelter cabin,” and pioneered two new routes on the north face in 1931 and 1932.

In Trail and Timberline, Lavender wrote of one section of the 1931 climb, “It would have been madness to attempt to go on without rope-sole shoes, pitons and karabiners” but in 1932 they returned better equipped for a more direct climb; the state-of-the-art use of pitons for lead protection were recorded in Gordon William’s journal:

I belayed the rope over a projection of rock, and Mel cautiously stepped out over the abyss. It seemed an age before he reached a ledge which would accommodate both of his feet at once. This ledge was half way along the traverse, and the belay seemed puny enough at that distance. From his position the leader drove a piton into a crack at arm’s length above his head. To the piton he hung a karabiner, and in that the rope was snapped. With such additional assurance, the first part of the traverse was duplicated, except that the chimney was, if anything, a little more difficult than the face. Securely belayed from the summit above, I next and then Dwight reached the top. Once up, there was nothing to do but write out a record and dread the descent which we did aloud and unabashed. The record, à la paprika can, had to be wired to the scanty top, a nerve wracking procedure in itself. (1933 AAJ).

We’ll finish this section on Lavender’s contributions to the tools and techniques of climbing, with a passage from David Lavender, who wrote a poetic description of the new kind of lead climbing he and his brother and others were doing in the early 1930s, “why the climber employs his rope, his belays, his pitons, and karabiners15”:

The rope is also a visible sign of the intense teamwork which binds a climbing party together. For instance, your leader is plastered against a sheer cliff. His face is red with exertion; sweat glistens on his forehead. Previously he has stood on your shoulders—a courte-échelle to reach a narrow crack. Into this he has jammed an elbow and knee and fought his way upward via a series of convulsions. Now he has left the crack, and his main support is the friction of his hip and hand pressed hard against the sloping stone. Cautiously he reaches out, tests a new hold for solidity, rolls his weight forward. He is anchored somewhat. He has driven a short steel spike, a piton, into a crack in the rock and fixed his rope to it with a snap-ring karabiner, so that the cord has support out on the cliff face like a belt run through a loop in a pair of trousers. If he slips, this pivotal point will limit the arc of his fall-provided you have taken up a solid belay and can hold the rope fast the instant trouble develops. You brace yourself, passing the rope around your shoulders or back, for you never in the world could stop a hurtling hundred and sixty pounds of man with your hands alone. And if you don't stop him and if the rope doesn't break, he will drag you off your perch; you will drag the fellow behind you, and suddenly the rope, instead of being a life line, becomes a suicide pact. Very carefully you pay it out, never letting it go slack and tangle on some projection, never pulling it so tight that it cramps the climber ahead. With this moral parachute tied about his waist, knowing that the chances of a fatal fall are reduced to a minimum, he is able to cross the ticklish spot. And when he reaches a solid stance he plays turnabout by guarding you while you come up-climb- ing the cliff and not the rope; weasling that way is mountaineering's prime form of cheating (One Man’s West, 1956—interesting also to note that “roping-in” was cowboy slang for cheating at the time).

The Growing Acceptance of Pitons

The adoption of pitons in North America was similar to the reputed experience of bankruptcy: “gradual, then sudden.” The “gradual” had been going on for decades; the “sudden” arrived in the early 1930s when writers and editors fully acknowledged the usefulness of pitons for great climbs and more climbers began making their own pitons, along with increased availability of pitons from Europe, both from mail-order and from traveling climbers. In addition to “old timers” like Blaurock adopting the latest tools wholeheartedly, there was also a new breed of younger climbers starting out climbing with the new tools and techniques and would push new levels of bolder and more difficult climbs in the 1930s (e.g Robert Ormes, next chapter).

Two articles in the 1932 American Alpine Journal left no doubt about the direction of rock climbing in America: Max Strumia’s “Old and New Helps to the Climber”, highlighting all the latest piton designs from Europe, and Rand Herron’s “The Great German School of Climbing: The Kaisergegirge” perhaps the first article not nationalistically mocking so-called ‘Munich school’ as “dangle and whack” climbers, and clarifying the exciting bold climbing that had developed in the Eastern Alps, as well as the challenges of “tension climbing” and where it was appropriate.

To Be Continued…

The next chapter will focus first on the developments by the East Coast climbers, many of whom traveled to Eastern Alps once the axis borders eased, starting with Lincoln and Miriam O’Brien who also became evaluators of the new tools. And as the availability of pitons increased by the mid-1930s when even shops in the more visited France were offering a fine assortment of quality pitons in their inventory (Pierre Allain). So in the 1930s, with the new tools in hand, American climbers would soon “catch up” with the standards in Europe that had been established three decades prior on routes like Campanile Basso. 1930s Routes on Mount Waddington, Shiprock, Yosemite and Zion walls, as well as new developments in the Tetons and Bugaboos, were among the hardest climbs in the world at the time, and we’ll look at the developing tools and techniques of the 1930s next.

Postscript: First Mail Order Pitons from Europe

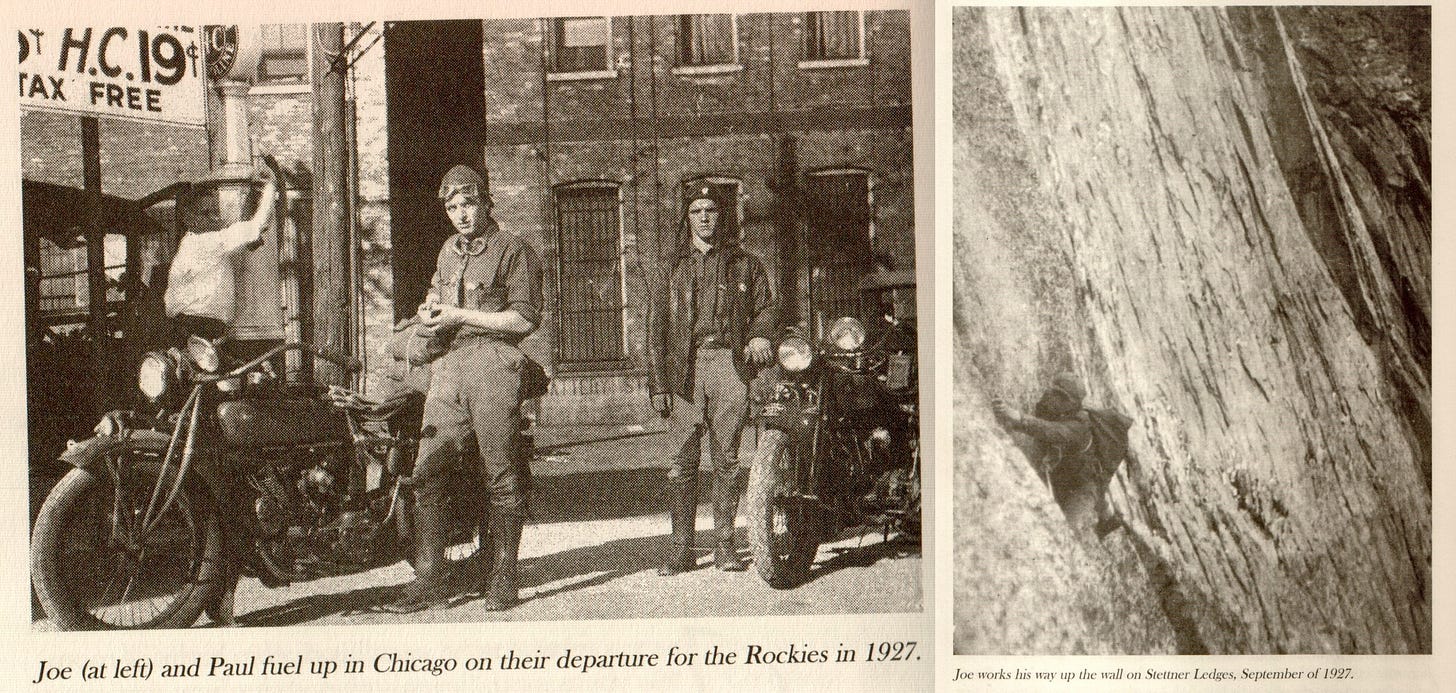

The astute historian will recognize that one of the great climbs of the 1920s, and a favorite among legendary climbing adventures that began with a long motorcycle ride, has not yet been mentioned. Joe and Paul Stettner climbed a new difficult rock climb on the east wall of Longs Peak in 1927, but the climbing community at large did not know of the ascent or the methods used until many years later, a time when pitoncraft and sources for pitons had become more common knowledge. In the 1930s, Sporthaus Schuster in Munich and Mizzi Langer in Vienna were recommended in the journals as sources for pitons, but probably few other than the Stettners knew of their availability in the 1920s. It was only in retrospect that Stettner Ledges on Longs Peak became a milestone in the shared knowledge of new tools and techniques16. (footnote)

MANY THANKS

Many thanks to the many historians and friends who have helped with this chapter: Chris Jones, Dudley Chelton, Jeff Achey, Katie Sauter, Steve Quinlan, Jack Tackle, Maurice Isserman, Christian Beckwith, Stuart Green, Rustie Baille, Marty Karabin, Ed Webster, Renny Jackson, and others. It is great fun to bounce and share ideas. There is no doubt I will need to make revisions and (hopefully minor) corrections to this piece of research, so please if anyone sees even small errors, please comment or email at deuce4@bigwalls.net

Copyright © John Middendorf 2022.

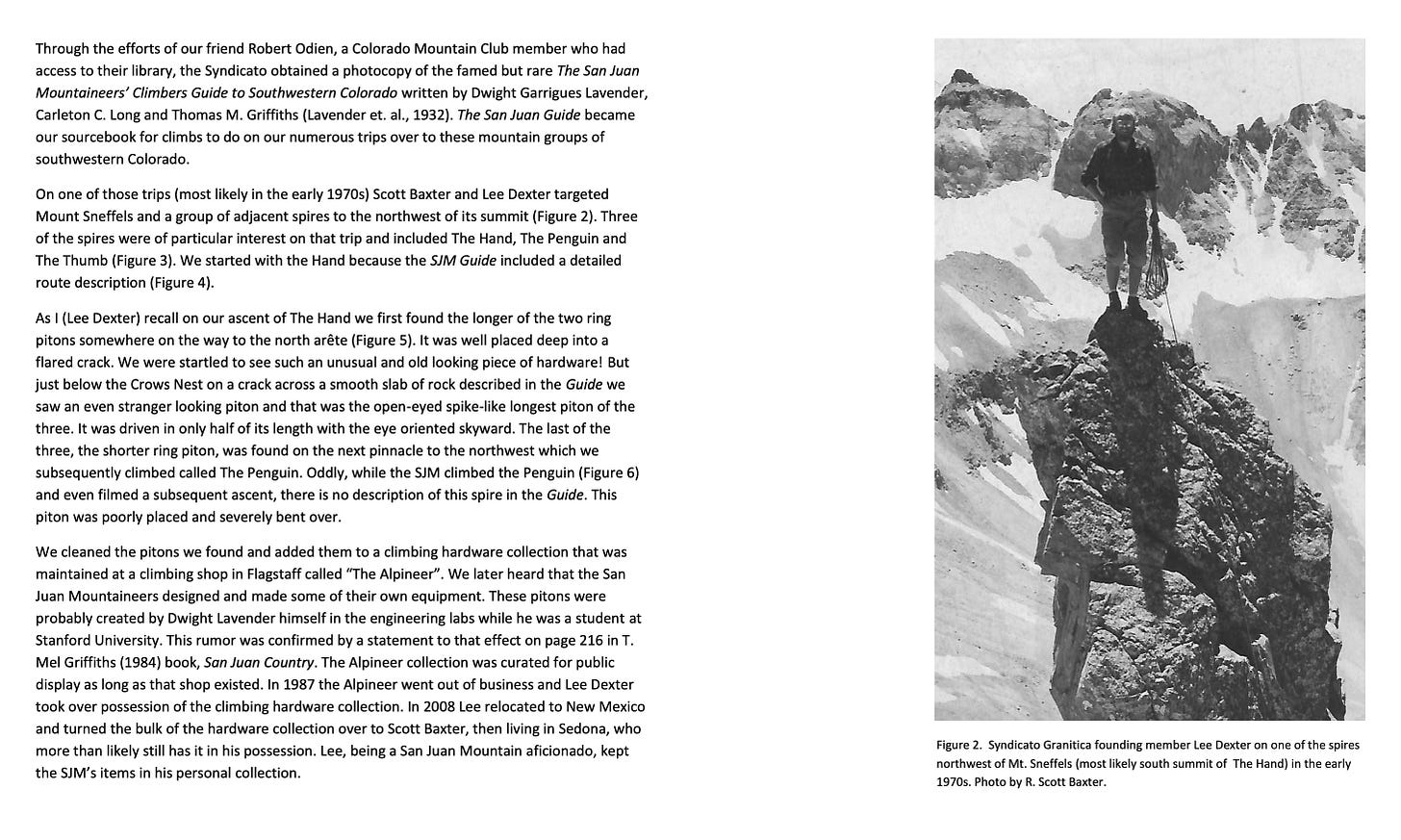

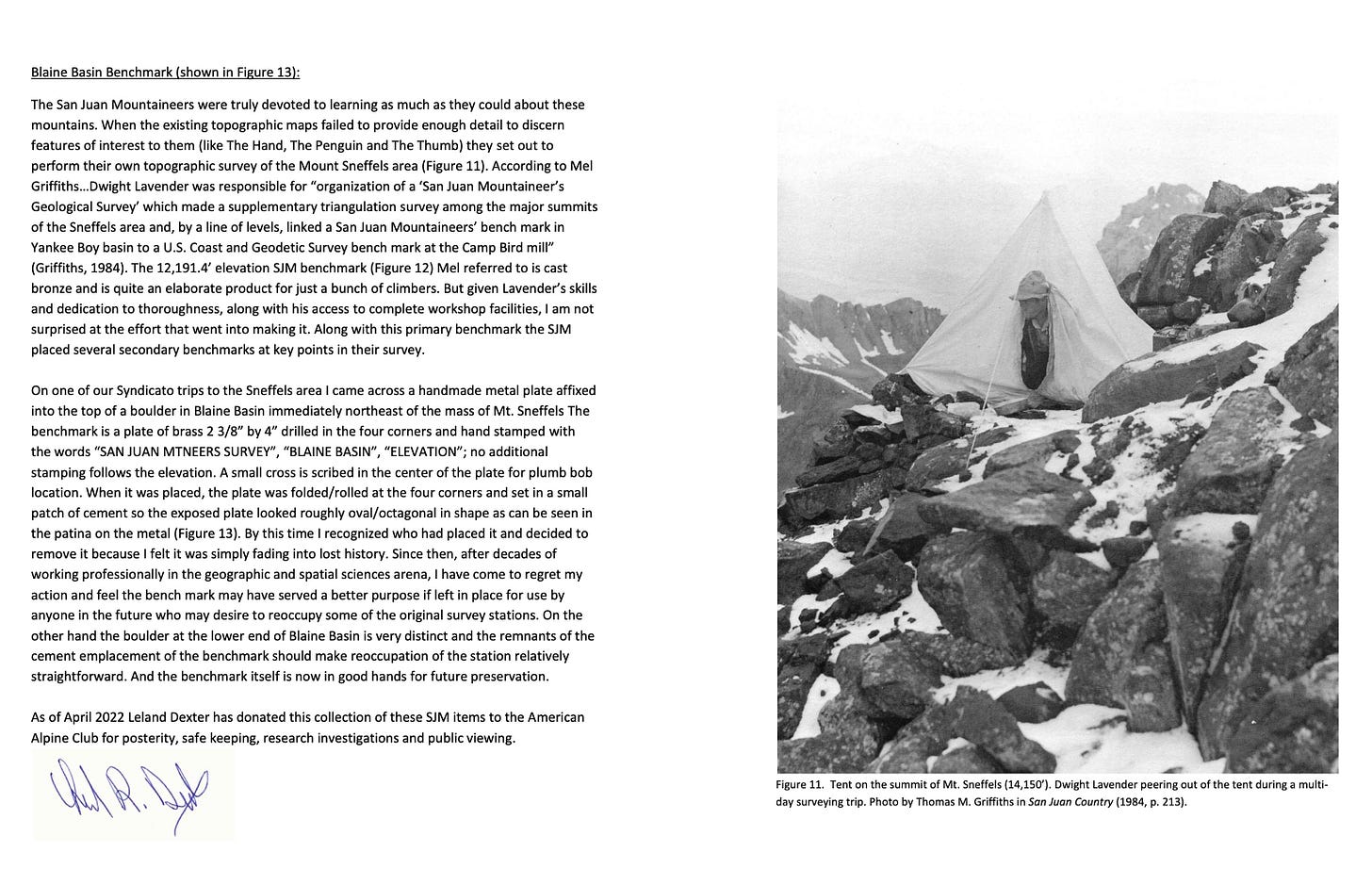

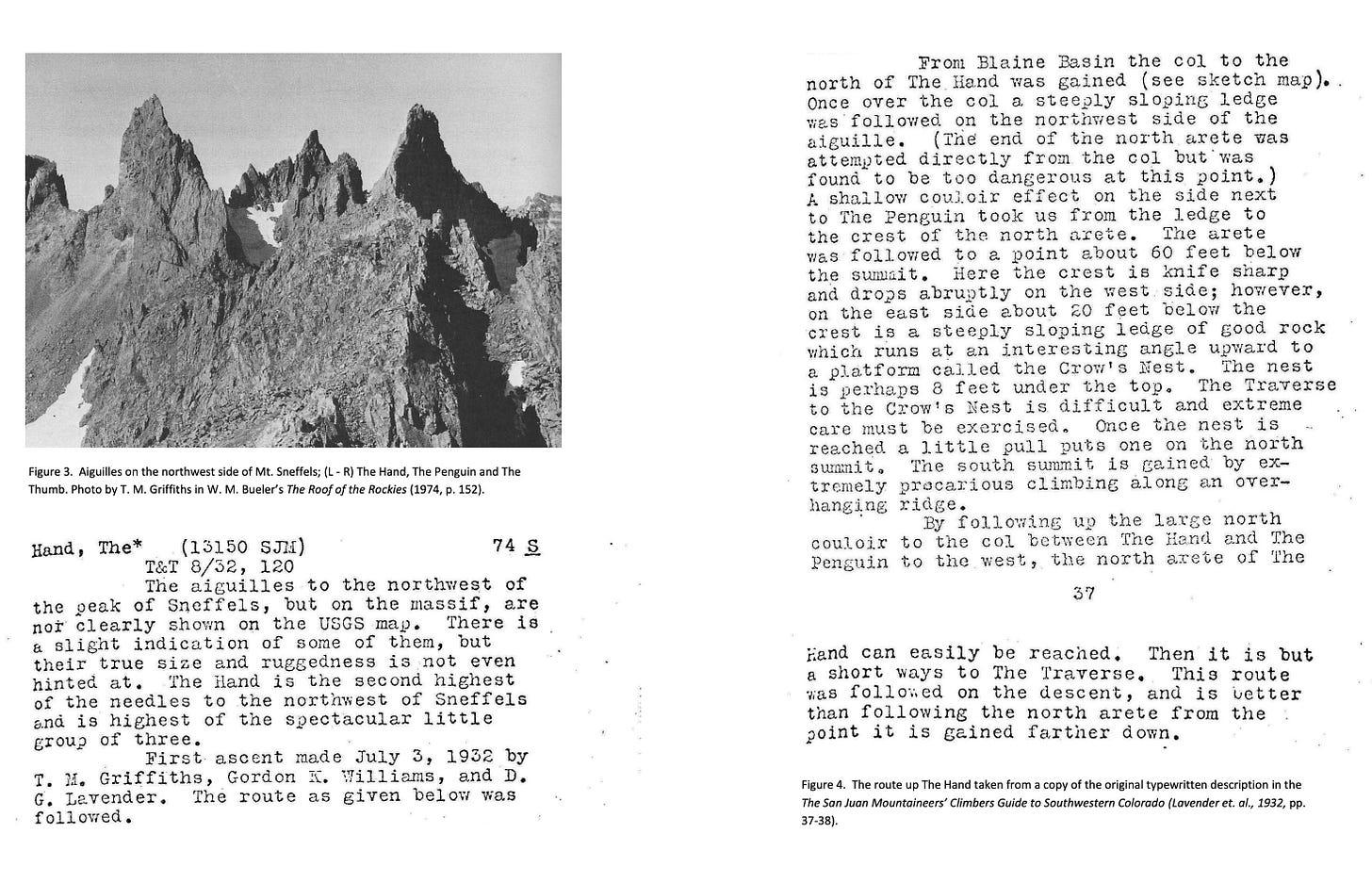

Appendix—Leland R. Dexter: Some Artifacts Created and Used by the San Juan Mountaineers: Provenance and Curation, April 27, 2022

Appendix/Scrapbook images

More early Winds photos from the 1924 trip (AAC Library):

And by the way, The American Hermann Buhl mentioned here as one of the key influencers in piton protected lead climbing is from an earlier era than the much more famous Austrian Hermann Buhl. I have been asked to make that clear!

I am getting some feedback on this one. I think one key evidence that the Colorado climbers, and not Underhill, led in terms of best rope work technique is the fact that Underhill wrote about the European around the neck rappel, while Lavender introduced what we know now as the Durfersitz, with the rope under arm. They are quite different, try them (with heavy collar jacket). The Colorado version became prevalent in the USA, and then even back in Europe in 40s.