The envisioning of pitons, USA 1920s (Miriam O’Brien)

USA adoption of pitons 1920s-1939 (part B) East Coast USA 1927-1933 (continuing mechanical advantage series by john middendorf)

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Changing standards, 1920s

In 1920s America, thrilling tales of polar and Himalayan explorations featured in national news headlines, as more remote inhospitable parts of the globe and difficult high summits were probed, and the alpine clubs filled most of their journal pages with mountaineering objectives. Meanwhile, American rock climbers were quietly establishing their own standards first on gymnastic crags, then on ‘impossible’ summits, challenges that required maximum efficiency, due to weather, remoteness, or other factors. The wider range of the mostly metamorphic and igneous geology in the United States (compared to the mainly sedimentary mountain climbs of Canada) offered unimaginable possibilities/dreams on walls of granites of every color, sandstone canyons and spires, tall volcanic plugs, and varied sedimentary cliffs—climbs not possible without new methods. European tools were increasingly accepted, and as pitons, carabiners, and climbing shoes became standard equipment, the ‘rules’ progressed dramatically.

Initially, there were strict limits on using hardware directly to gain upward progress; otherwise, as the timeless argument runs, anything can be engineered rather than ‘climbed’. As a “mechanized-mountaineering” counterpoint, Angel’s Landing trail in Zion, with much steel and sculpting, was completed in 1926 to a summit once thought “only an angel could land on" (Frederick Fisher, 1916). The ‘sporting’ aspect had to be considered as new climbing styles developed.

New strategies with artificial anchors

Consider how the new anchoring tools inspired new ‘lines’ up imposing vertical landscapes, as climbers started to emerge from the major weaknesses (chimney and corner lines) to the exposed and elegant lines up sheer faces, where natural security is less likely. Pitches on hard climbs were often short—the Whitney/Gilman route on Cannon Cliff, which famously did not use any pitons, was originally done in 1929 in 17 pitches but is now a five-pitch 5.7 (the first added piton anchor—in the form of a steel pipe—was installed two years after the first ascent). An ‘artificial’ anchoring tool provides more options where climbers can establish a safe place to belay, and allows climbers to extend their leads. A piton belay prior to a difficult section kept the belayer close for the next lead (footnote). Since shoulder stands were fair game, a piton anchor provided more options where such progress could be performed safely. And indeed, this is how pitons were initially used, but by the early 1930s, lead climbing as we now know it, with longer pitches and pitons and carabiners as inter-pitch anchors for the running rope became standard practice. (footnote).

footnote: The idea of a ‘fall factor’ was not considered. Catching a short fall nearby was much less feared than a fall far from the belayer, and indeed with static ropes of the day, a short swinging fall with less kinetic energy was probably more easily caught by the belayer—the idea of dynamic belay coming to fore around this time. To clarify, a ‘belay’ once meant any natural or artificial anchor but now means a solid place where one climber remains to feed rope to the leader, or bring up the second; it was also known as ‘security’. A ‘pitch’ refers to the climbing between belays. Getting a shoulder stand from a partner had been considered fair game since the mid-1800s as it did not require any ‘artificial tools’ except for the rope. Also considered fair game was “to get a rope over a distant target by first throwing a small cord to a lead,” as described by Miriam O’Brien to describe a technique Alfred Couttet used in Chamonix. Regarding the Whitney/Gilman, Bradley Gilman (a member of the Harvard and Yale Mountaineering Clubs) and Hassler Whitney were fresh back from guideless ascents of the Grépon, Grand Charmoz, and many other alpine and rock routes around Chamonix (routes that mainly required pitons—if at all—for roping down) when they climbed their route on Cannon in 1929.

Shared information of new technology progressed, and as the piton became acceptable as an anchoring device for roping down and belays, disclosure of their use was generally only reported (sometimes by others) if the use broke convention. The initial epicenter of both acceptance and of reliable supply of the new tools in North America was on the East Coast, first led by a group from Harvard, Yale, and other university mountain clubs, followed by the Appalachian Mountain Club, with many members who had visited Colorado and Wyoming, where striking lines up the bigger mountains were being climbed and imagined, and new safety techniques were developing. But first, a quick story on East Coast climbing history:

The Pinnacle, 1910 and 1928

The early history of North American mountain climbing tools and techniques has been covered previously, and as in other areas, there are sometimes isolated events “ahead of their time”; some are known such as the climb of the Third Flatiron in 1906, and probably many unknown. One of the more surprising discoveries by Laura and Guy Waterman in 1984, “stumbled on by sheer luck”, was in a sketchbook from George Flagg, a turn-of-the-century newspaper cartoonist with a prolific collection of sketches of the era. As historians of Northeastern climbing history, to their wonder and joy, inside one sketchbook were a number of illustrations depicting a 1910 ascent of the Pinnacle in Huntington Ravine, a feature that became a celebrated “first ascent” eighteen years later when climbers were expanding their toolkit and refining their rope skills for the big rock challenges (the later route is a slightly more direct and challenging line, but the idea that the “unclimbed feature” was first ascended in 1928 was debunked). “Seventy-four years is a long time to wait for glory,” the Watermans write of the 1910 ascent. The challenge in Huntington Ravine is not just technical—Mount Washington is the highest peak on the East Coast and gets hit by some of the worst weather in the world, requiring efficient rope systems and teamwork to move fast. The ascent was at a level of efficient and bold roped climbing unmatched for a decade.

Footnote: The history of northeastern United States climbing is well documented in Laura and Guy Waterman’s Yankee Rock and Ice (1993).

Author note: Huntington Ravine is where I first learned to ice climb. One season my friend and fellow Dartmouth student Thom Englebach and I embarked on three trips into the ravine. Our prior experience was a single-pitch toprope at a scrappy crag near campus. On our first trip, we were being led by two more experienced upperclassmen, who had the ropes, ice screws, and gear. On the hike up, one of them punctured his leg when he fell onto his ice axe on the icy trail, and they both bailed. Thom and I continued up to check things out and ended up soloing Odell’s Gulley, a moderate low-angle hard-ice route. As Thom noted, “Too cold to belay” so we made our way up there for another solo trip, this time the Pinnacle Gulley, considered a hard steep ice route and not often soloed. Later that season, perhaps with a bit more local ice experience, we tackled Damnation Gulley, a mostly moderate ice runnel but with a 10m steep vertical waterfall section about two-thirds the way up the 300m gulley. At the top of the waterfall, there was another party, belaying in a big snow drift. Thom got up there first and noticed that the team ahead was about to cut loose a huge ledge of snow and ice down the waterfall section, where I was still plodding my way up and pretty pumped. Thanks to Thom’s imploring, they all remained motionless until I got to the snow ledge, whereupon they let loose a huge avalanche that would have most certainly taken me out on the steep bit below. Thanks Thom!

“Great leap forward” Northeastern USA 1928-1933.

In the Northeast USA, there was a “great leap forward” in climbing standards from 1928-1933: “by 1927 little had been done save the easiest and most obvious routes in the smaller area, The single year 1928 saw great changes” (Yankee Rock and Ice, 1993). In addition to the known ascent of The Pinnacle, the big south wall of Willard in Crawford Notch, and the sheer 300m Cannon Cliff in Franconia Notch were also climbed in 1928 (more on Cannon later).

This period coincides with progressively systematic exposés of the new hardware (sometimes called “alpine pitons’) in the American mountaineering journals. An early explanation (1927) explains the piton as a “roping down” anchor, but also as means to tension traverse; this is precisely how piton-protected climbing became more accepted several decades prior in Eastern Europe (see The Climbs of Tita Piaz, AAJ 2022). Lincoln O’Brien writes in the Impressions of Dolomite Climbing (Harvard Mountaineering Journal, June 1927): “It is fairly easy to find a place to drive in a piton—called chiodo in Italian. There is a good deal of discussion about the etiquette of using pitons. The consensus of opinion seems to be that they may be used for the rope, as a security, or in “roping down”, but that their use as handholds isn’t proper. Mechanical methods of climbing are used more in the Dolomites than elsewhere… When one must get across a narrow slab and cannot climb it, he can drive in a piton, thread a rope through it, and pendulum himself across on the end of this doubled rope” (footnote).

Footnote: Lincoln O’Brien here is explaining the Dülfer self-belayed tension technique of using a separate rappel rope (vs. rope tension from a belayer—the preferred method with the availability of strong carabiners). The quote also indicates that the Northern Limestone Alps, where piton techniques had evolved even further, were still unknown to O’Brien in 1926. He also describes the technique of tyrolean between two summits, no doubt informed by the famous Guglia De Amicis in the Dolomites.

Thawing of Anglo piton acceptance (Pinnacle Club, 1920s)

Pitons were adopted to accomplish great personal goals in the 1920s and 1930s. Journal readings reveal the thawing of piton acceptance both in the UK and in the USA began with women, many of whom were learning the craft with top guides on some of the hardest rock and alpine climbs of the mid-1920s. The piton is objectively considered in terms of the experience of using them on the wild vertical and of their future potential. Progressive British journals such as the Pinnacle Club Journal publish stories of piton-protected routes without a lot of qualifying verbiage on ‘moral’ issues (the rules of the game).

In the 1926-7 journal, Lilian Bray describes a spot where she and her guide Tita Piaz were unsure of the route: "Up he went. It was so difficult that I doubted at first whether we were right; but about half way up a piton was discovered, showing that we were not making a new route. To this Piaz was able to attach the rope and ensure his safety. It was a very strenuous bit of climbing, and proved much the most difficult pitch of the climb.” —Lilian Bray, Pinnacle Club.

As the technique and use progressed: “The rocks were so rotten that it was impossible to find a sound belay anywhere, or even a rock firm enough to hold a piton, and it was not worth risking a long and unsecured traverse across such treacherous ground.” and “We hammered pitons into the rock and tied ourselves on.” Ruth Hale in the Tatras, 1932.

For Lilian Bray’s early climbs in the Northern Limestone Alps, see The Kaisergebirge, Alpine Journal 1925 Vol.27, p.279, and for more on early British women climbers leading at a high level, see articles in The Pinnacle Club Journals, including Dr. M. Taylor (Flight to the Mountains, 1926), Susan Harper, M. Jeffrey, Ruth Hale, Maud Joachim, Wells, Dorothy Pilley (later “Mrs. Armstrong Richards”), Marjorie Heys-Jones, Brenda Ritchie, Ursula Corning (South Tyrol-or Thereabouts in the 1934 Alpine Journal), Nea Morin (Ladies Alpine Club) and many others. A brief commentary on the representation of women alpinists in the early period is here, but the research on the comparable accomplishments of many women climbers of this period is incomplete.

Contrast the notions of the author of the best-seller Alpine Pilgrimage (1934) Julius Kugy, considered a “father of mountaineering” and darling of the British Alpine Club (which famously did not admit women until 1974): “To fix chains and ropes and then describe them as easy and uninteresting—as in the case of the Matterhorn—is contemptible. (Kugy) resents the paint-splash and the chains and pitons which make mountains climbable by the incompetent. He dislikes the competitive spirit, and the kind of recklessness that takes unjustifiable risks. He himself was always prudent. He climbed only with the most competent guides.” (Susan Harper in the Pinnacle Journal). (footnote)

Footnote: When pitons were noted in the Alpine Journal by the British hardmen, justifications would sometimes be explained with long footnotes, i.e. on NW face of Wetterhorn (1929): “This was the only 'artificial aid' used apart from the rope and was employed only as a safety device and not as an essential to the ascent. And as such was thoroughly justifiable. Our (previously dismissive comments in AJ41) remarks referred to the objectionable modern method as practised chiefly in the Eastern Alps, of driving in a series of pitons to be used as foot and hand holds in scaling overhangs otherwise impossible of access.” (N.S.Finzi, AJ42) Of course, many climbers in the Eastern Alps had been using pitons in the same sporting way as the writers describe on the Wetterhorn for several decades. The same volume describes a new route on Triglav in 1929 by Jože Čop, Stane Tominšek, and Miha Potočnik where ten pitons were used on a single desperate pitch.

Brits in the Dolomites

In the pre-WWI era, many British climbers had a rich history of hard steep multi-pitch climbing with talented Dolomite rock guides such as Antonio Dimai (who only used pitons for security and descent), Angelo Dibona, Giovanni Siorpaes, Michele Bettega, Sepp Innerkofler, and Agostino Verzi—a few of the great steep rock climbing guides of the era. May and Ludwig Norman-Neruda, H.K. Corning, Edward Broome (Dolomites up to Date, AJ1907), H.Bowen (Some Dolomite Climbs, AJ1913), Emily Hornby, Maud Wundt-Walters, and Beatrice Tomasson were a few of the most accomplished British Eastern Alp climbers of this era, dating back to the 19th century. A top-level testpiece like the 1890 Schmitt route on the Fünffingerspitze was the frequent end-of-season objective— periodical AJ reports of fatalities on such routes grimly cautioned those who were still dreaming of that level of climbing (Norman Neruda, the ‘well-known rock climber’, died on the route in 1898 while climbing with his wife May and a friend).

In the 1920s, however, Dolomite climbs appear to fade in popularity among the elite Alpine Club members, as the focus shifted to more alpine and guideless climbing. Perhaps in terms of gender roles, as pitons became essential on the hardest Dolomite steep rock routes, the leading male climbers were less willing to be second on piton-protected climbs with a foreign guide, such as Tita Piaz and the sons of Antonio Dimai (Angelo and Giuseppe), forerunners of new climbing and guiding techniques. This left the field of challenging bold rock climbs more open to the athletic women in the UK and the USA, many of whom first learned their skills with talented Eastern Alps guides, then became leading climbers of spectacular bold free (or mostly free) climbs.

Footnote: A major European rock climbing trend of the 1920s was the advent of the “Sixth Grade”, with its focus on the tallest big walls and usually involved some aid. Sixth-grade routes became the main rock climbing game in the headlines with incredible challenges overcome; perhaps a few of these routes were deserving of the “whack and dangle” critique, as aid and larger racks were sometimes used to compensate for lack of bold free climbing in some cases, despite the higher specified “grade” (see this post for the 1930s fixation on sixth-grade routes). In 1926 the grade was defined: “Any route or pitch that is climbed without the aid of a piton (for upward progress) is Grade V.” By contrast, the lesser reported fourth and fifth ‘degree’ (Grade V) climbs involving bold free-climbing and minimal use of pitons were probably more influential in inspiring the adoption of piton-protected steep rock techniques in America, igniting a boom of new climbing with many leading women at the fore. See also Jack Longland's view of why Alpine Club climbers not pushing standards “Between the Wars, 1919-1939,” Alpine Journal 62, Nov. 1957, 83-98.

Footnote: An explanation of (global) bias of marginalized groups of mountain climbers, with a focus on nationalistic themes, is well researched by Tait Keller, Apostles of the Alps, Mountain and Nation Building in Germany and Austria, 1860-1939, who writes of contemporaneous attitudes in Austria-Hungary: “Male chauvinists saw a direct connection between the mechanization of the mountain and the feminization of mountaineering.” Some women found an ironic voice: Emmy Hartwich (later Eisenberg) in Die Frau in den Bergen. Eine heitere Plauderei über ernste Dinge (“The woman in the mountains. A lighthearted chat about serious things”) in Mitteilungen des Deutschen und Oesterreichischen Alpenvereins 50, no. 3 (1924): 26–28, describes a percieved view that women lacked the ability to skillfully to handle a rope because “Having to wrap a stubborn rope, sometimes wet, sometimes dirty, around their body wasn’t in the nature of a woman”, and pokes fun at how the “female creature had to be switched on” for a man following a leader. Hartwich wryly parodies the ‘stupid recklessness’ that men called ‘courage’, an era peaking with mythic stories of climbers with bravado brashly heading into the unknown, often with glorious failures and heroically portrayed death (e.g. the many failed “attacks” on massive alpine walls, often with limited tools and techniques, that end with grim fatalities). It should also be noted that alpine club journals were not completely devoid of women’s accomplishments; in 1936, a time when Olympic nationalism was at its peak, the Deutsche Alpenzeitung published “Die Frau in den Bergen” highlighting leading women of the era.

European training grounds

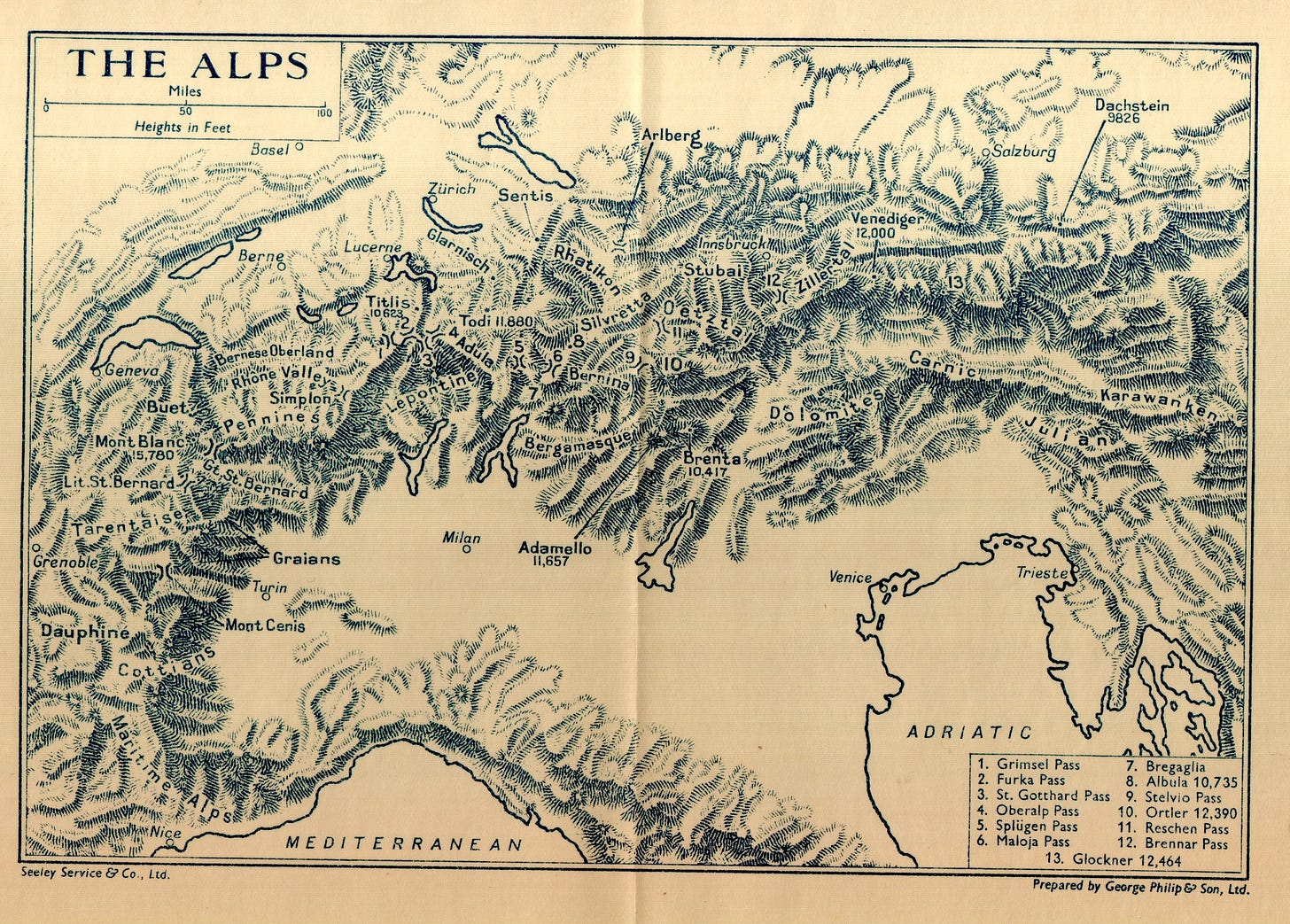

For American climbers, venturing across the pond to the Western Alps to climb alpine and rock routes had been a rite of passage for some time. Zermatt and Grindelwald in Switzerland were common destinations for alpine climbers interested in mountains like the Matterhorn. For rock, popular routes included the Dent du Géant and the famous Grépon, dream climbs for many climbers; Chamonix in France is the epicenter of these climbs.

As the Dolomites became increasingly more “friendly” to American tourists after Italy’s annexation of south Tyrol (1919), the previously war-torn border town of Cortina in Italy became another prime destination for American rock climbers, with accessible peaks noted for their difficulty, exposure, and less severe alpine weather. For rock climbers, the Cinque Torri (‘five towers’) was an initial target, with plenty of good training climbs as a prerequisite for the longer routes.

Footnote: In 1929, the American Miriam O’Brien famously climbed the Grépon “manless” with Alice Damesme in 1929. Miriam first led the crux rock climbing pitch in 1928.

Women’s climbing standards, 1920s

The varied attitudes of the British climbers are important to understand how the position changed in 1920s America, where most mountain climbers still followed and held fast to the traditional and strict no-piton ethic; alternate information from the Central Empires (inc. Germany and Austria-Hungary) had previously been limited during WWI, and any steel hardware techniques were considered simply as the slippery slope to complete mechanization of the mountains.

Among women climbers, there were highly respected athletes from other nationalities, especially in the pre-WWI period, such as Jeanne Immink (Netherlands), Pavla Jesih (Slovenia), Irma Glasser (Austria), Vineta Mayer (Austria), Ilona and Rolanda Eötvös (Hungary), and Kathe Bröske (Zabrze, now Poland). And in the period leading up to the early 1930s, there were a number of up-and-coming European rock stars, climbing at the highest standard using the latest tools and techniques, such as Mira Marko Debelak in the Julian Alps and Paula Weisinger in the Dolomites. Among American climbers, perhaps the better-known leading international women rock climbers in the 1920s were from the French and Swiss Alps, such as Marie Marvingt in the early era and later Micheline Morin and Alice Damesme (footnote).

Footnote: Many of these pioneering women were not just climbers but excelled in a number of adventurous pursuits, including skiing, aviation (airplanes and balloons), mountain and polar exploration, diplomacy, you name it. In English-speaking alpine journals, it was more common to see reports of mountain climbers such as Dora Keen (USA), for her first ascent of Mt. Blackburn in Alaska in 1912 (the second major Alaskan peak after the famous Abruzzi expedition to Mt.Saint Elias in 1911—she also had climbed testpiece rock routes in the Alps); Freda Du Faur, for her ascent of Mount Cook; or Hettie Dyrhenfurth (Swiss) for her participation in an expedition to Kangchenjunga (1930). It would be fair to say the comparable rock climbing accomplishments by women in this period have been marginalized (or absent) in many histories, and still incompletely researched, and discussed in this post; primary sources have many vague references to little-known climbers probably at the top of the game (e.g. Miss Gret, Miss Fitzgerald?, though some were known internationally, e.g. Rita Graffer and Mary Varale). The few who wrote books in this early era are happily remembered, such as the Ladies Alpine Club member Nea Barnard (later Nea Morin), who published her memoirs in A Woman’s Reach (1968).

Whence inspiration?

Climbing is a theatre where an actor’s inspiration comes from a range of heroic stories often of an unfamiliar place, fantastic and wild, with challenges approached and overcome. The central act is the struggle for the clear summit goal, or perhaps an intense experience along the way (footnote). The heroes and their imagined experiences beckon. As there was not a lot written about the strongest contemporary women rock climbers in the 1920s English-speaking journals, along with the fact that few clubs stocked the Eastern Alp Journals in their libraries, it is not clear to the degree to which the leading international women climbers were inspired by each other, but archetypes in other fields also led by example.

In the mid-1920s, American climbers first learned the potential of the ‘special techniques’ developed in the Eastern Alps on difficult Dolomite climbs. Several of these climbers were women who were pushing the boundaries of convention on the most feared rock climbs of the Alps. One of the inspirational legends in this respect was the internationally renowned Gertrude Bell, so let’s first consider one of her epic climbs in Switzerland.

(footnote: here I will sneak in a personal story, of the bigwalls in the alps being climbed for the first time by Bonatti and others, with storms a central feature).

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926)

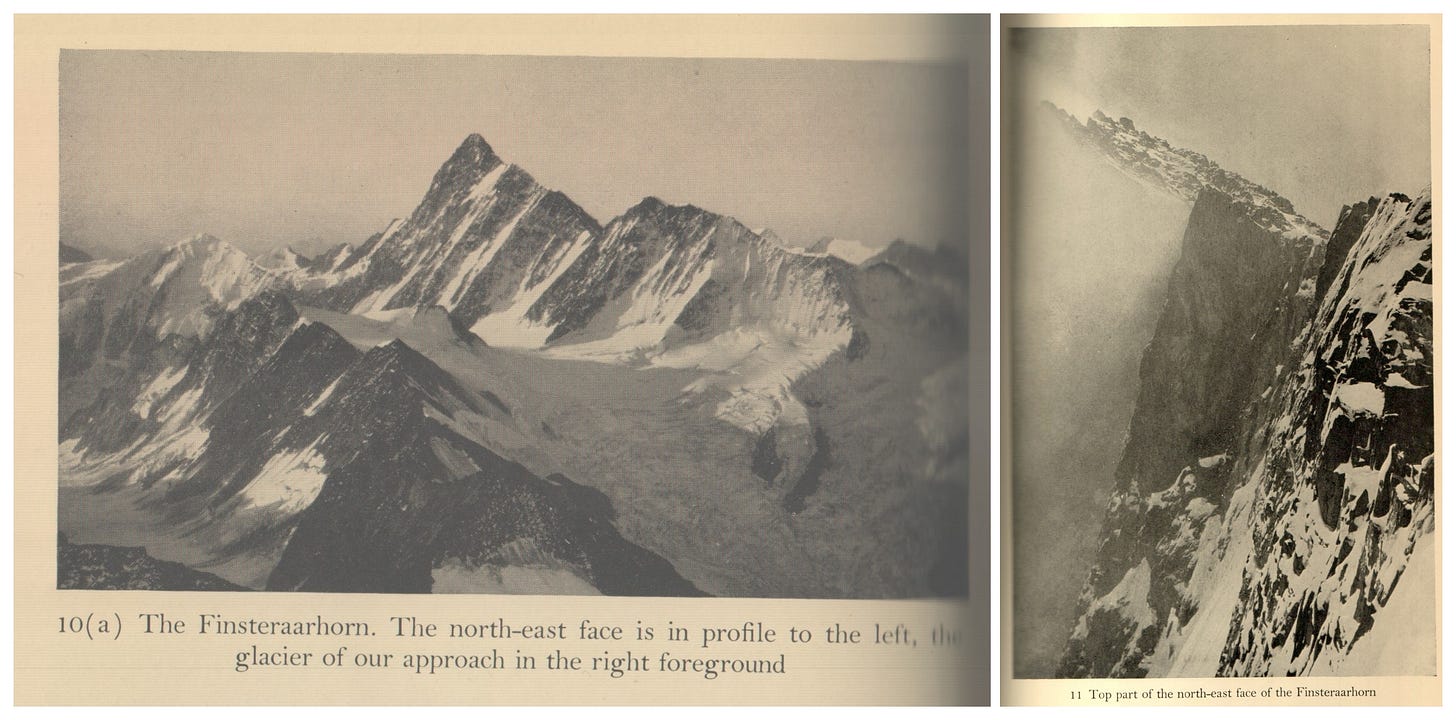

The remarkable English polymath Gertrude Bell focused on climbing for five years (1899-1904) with a phenomenal list of climbing accomplishments, still enviable decades later. Among many of her visionary climbs, she imagined an improbable new climb up the steep knifeblade NE rib of the Finsteraahorn, the most prominent peak in Switzerland. Her 1902 attempt on this elegant line ended short of the summit, and the account of their descent became an epic tale of the era, an epoch of exploration already abundant with gripping survival sagas from around the globe. As bad weather set in at a particularly perilous section with tenuous route finding, Bell and her guides Ulrich and Heinrich Fuhrer’s retreat involved two days and nights amidst avalanches and desperate bivouacs, with many close calls managing endless rappels with frostbitten hands and feet. Only through incredible teamwork, courage, and perseverance did the team survive. When this route was finally climbed in 1904, it established new levels of commitment on long alpine rock routes (1000m).

Gertrude Bell died in 1926 in the midst of a prolific diplomatic career in the Middle East, but her incredible career was celebrated in global news and she became an exemplar to many. Her line on the Finsteraahorn became a leading objective for the American climber, Miriam O’Brien. Among Bell’s difficult climbs, many were made possible with the state-of-the-art tools coming online at the time in the Eastern Alps. In her journals, she writes of some training climbs:

BERNER OBERLAND August, 1901: Yesterday my guides and I were up at 4 and clambered up on to the Engelhorn range to take a good look round and see what was to be done. It was the greatest fun, very difficult rock work, but all quite short. We hammered in nails and slung ropes and cut rock steps-mountaineering in miniature. Finally we made a small peak that had not been done before, built a cairn on it and solemnly christened it. Then we explored some very difficult rock couloirs, found the way up another peak which we are going to do one of these days. ... I shall probably stay here till Sunday morning which will give the snow time to get right. Then I shall return to my great schemes... (footnote).

Footnote: there are several other references to Gertrude Bell’s use of pitons (then known as ‘nails’), notably in 1902 on the Wellhorn, where she succeeded only ‘with the aid of an iron nail driven in the worst place and of a double rope.’ Miriam O’Brien notes of that climb, “At that time, apparently, pitons were not so much in disfavour with English Climbers as they later became!” (Give me the Hills, 1957). Regarding “cutting rock steps”, note that sculpting hand and foot-holds in rock with a hammer (or ice axe) was a tolerated technique well into the 1930s (see Rudatis, 1931).

Enter Miriam O’Brien (1899-1976)

In 1931 Miriam O’Brien reflected on Gertrude Bell’s great schemes, in “On Some of Gertrude Bell’s Routes in the Oberland” (AAJ), a tribute article that also revealed her own focus on steep visionary new rock-climbing lines. In the previous era, mountaineers were often modest in their published reports of varied difficulties, some even with extreme reluctance to make any claim at all, as in the case of the talented Benedikt sisters, who roped up with Conrad Kain. Miriam’s eight-page article on Bell dispenses with modesty and explains the raw commitment and severe challenges Gertrude Bell overcame, based on her own experiences and successes on the hardest testpieces of the day. Miriam became a leading climber amidst a group of East Coast American rock climbers in the 1920s-1930s period, which included many talented women such as Margaret Mason Helburn, Elizabeth Knowlton, Majorie Hurd, Betty Woolsey, Florence Peabody, Winifred Marples (British), Julia and Julia Colt (mother and daughter), and Jesse Whitehead (a Briton who moved to the USA in 1925).

Miriam O’Brien first roped up in 1920 on the Grand Muveran during one of her annual summer family vacations in Switzerland. Imagine: she loves the moment, and each summer returns to the mountains. In a mountain hut, she meets George Finch (footnote) who tells her, “You can do the Matterhorn.” Climbing becomes her game. On local Boston crags and later on climbing trips to the American west, she discovers her natural affinity for balance climbing on steep rock. In March, 1926, she joins Margaret Helburn on a winter road trip with the “Bemis Crew,” a group of hard-core alpinists and rock climbers within the Appalachia Mountain Club. The trip cumulates with steep rock climbs on “the walls of the cirques of Katahdin”, the highest mountain in Maine. Inspired by the steep unclimbed rock walls, a few months later, she travels to the Dolomites looking to engage the “right” guides to learn the craft. She writes, “In common with many women, I felt that these Dolomites were made just to suit me with their small but excellent toe- and finger-holds, and pitches where a delicate sense of balance was the key, rather than brute force. While it helps of course to have tough muscles, the prizefighter would not necessarily make a fine Dolomite climber. But the ballet dancer might.”

Footnote: This was in 1924. In 1922, George Finch, a native Australian, became well known for his high-point on Everest during the first serious British attempt. Finch was a freethinker who dispensed with confining “rules” when they held him back from his goals. A chemist by trade, he developed new portable oxygen systems for climbing the highest mountains, then considered, an ‘artificial aid’ in the same realm as pitons. He openly acknowledged his use of pitons in the mountains, publishing his memoirs in 1924 and writing of the need for artificial anchors on the west ridge of the Bifertenstock in Switzerland, a futuristic route for the time (1913). NB: from Finch’s The Making of a Mountaineer is possibly where the notion that ring pitons prior to carabiners required the leader to tie and re-tie after threading the rope through the ring of a piton. As information about pitons was limited in the English-speaking world, the use of slings (called rope rings) as often described in the Eastern Alp journals, was possibly unknown (or maybe they just did not have any—he carried the pitons in his pockets, and hammered them in with rocks).

First Dolomite Season

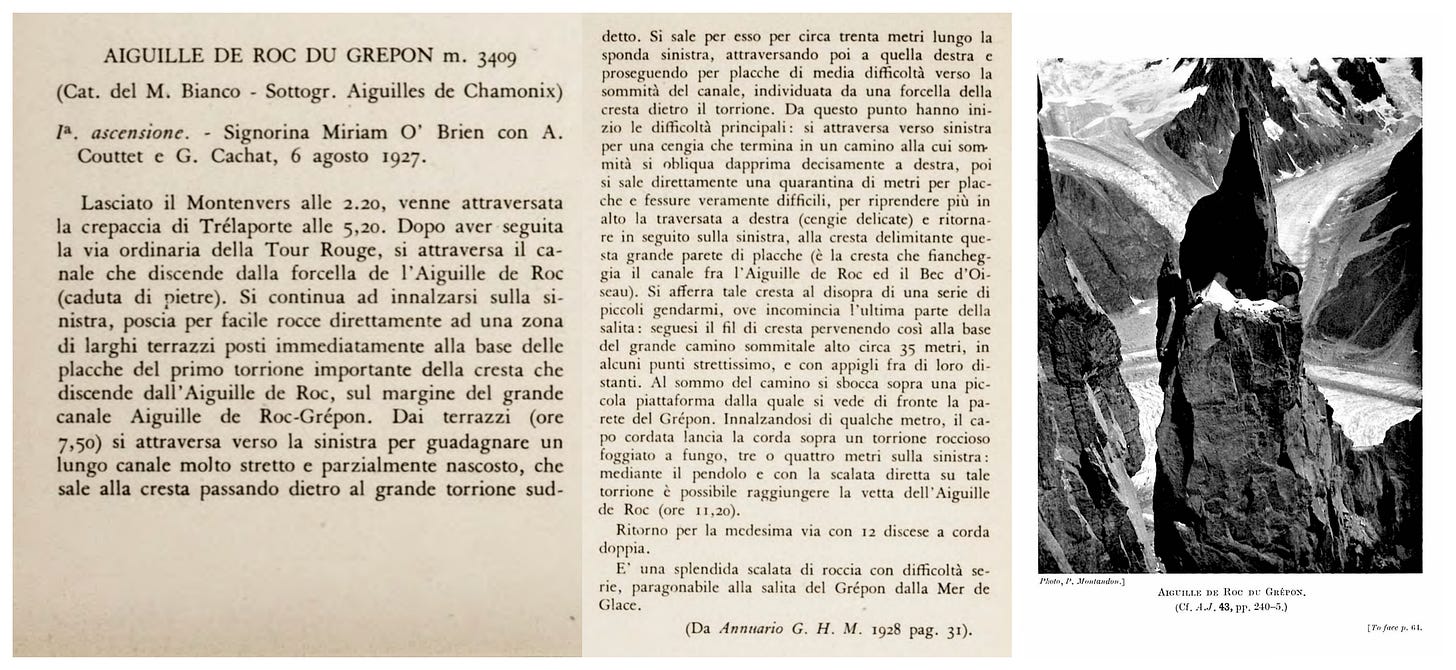

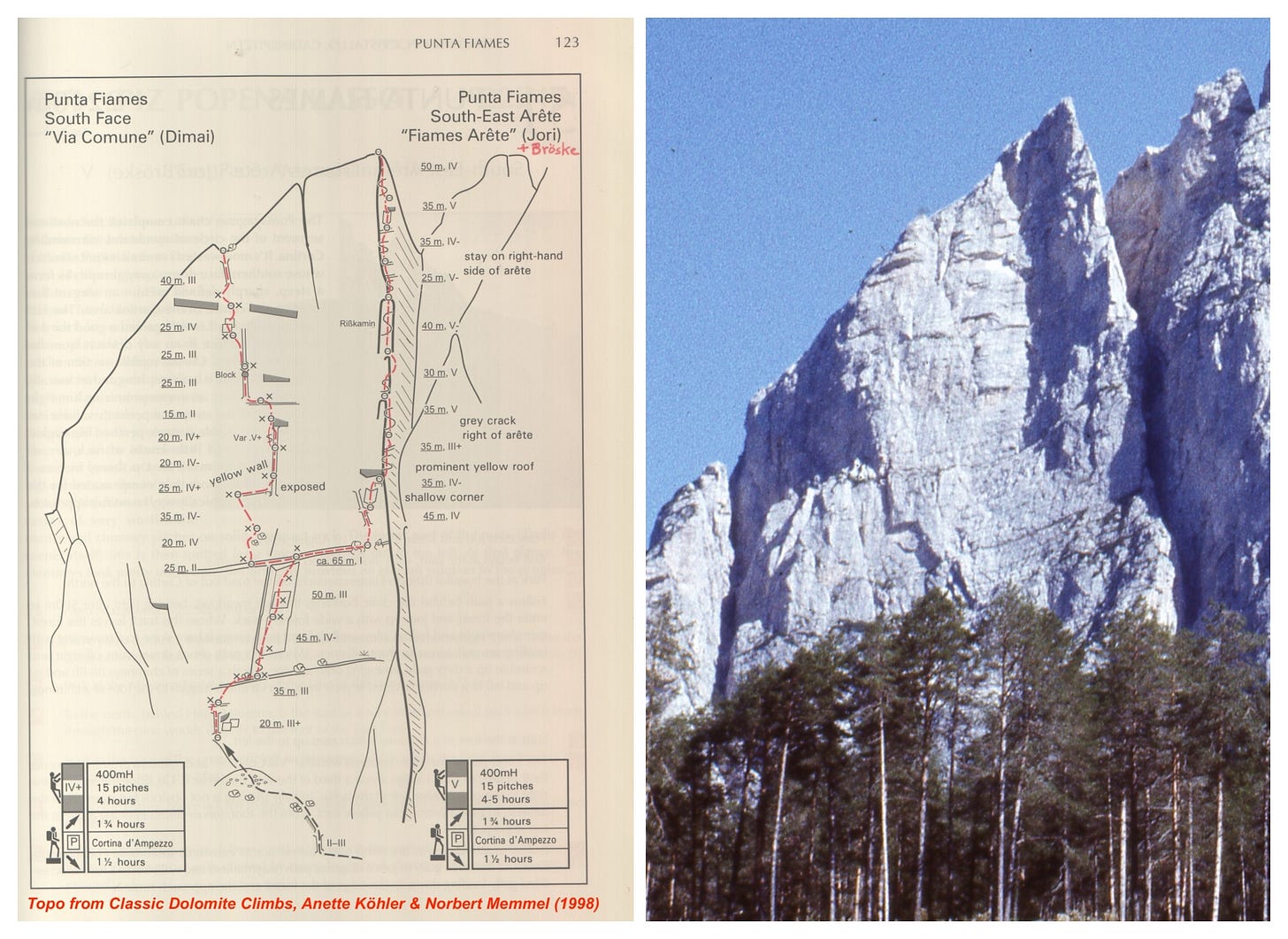

Indeed, Miriam proved to be a leading ballet dancer on rock. Planning her first trip to the Dolomites, she writes in her autobiography (1957): “Rock climbing was what I wanted. I would start in the Dolomites and later go on to Chamonix and its granite aiguilles.” Within a few prolific seasons of rock routes in the Alps (1926-1928), she was leading top-level rock climbs and becoming well-known for her ability on both sides of the “pond”. In her first year (1926), after a few training climbs, she climbed the Punta Fiames by the Spigolo, a futuristic 400m route established by Käthe Bröske and Francesco Jori in 1909, which followed a bold arete. Her understated report in Appalachia (Notes on Three Dolomite Climbs, 1926), notes how her guide, Angelo Dimai, led a difficult pitch with only a small fish line attached, as “the weight of the regular rope would be enough to upset his balance and pull him over backwards.” Though Miriam was second on the rope, this climb would have been considered harder than any of the long rock climbs in Colorado at the time (Crestone Needle or Alexanders Chimney) and thus harder than anything in America. Miriam would soon be leading routes of this difficulty.

Second Dolomite Season

In her second Dolomite season (1927), Miriam’s first route was “one of the most difficult in the whole Dolomite region”, the south wall of Torre Grande in the Cinque Torri range, a guided climb with her climbing partner Margaret Helburn. This was a state-of-the-art route, with piton belays and anchors strategically placed for the Grade V+ free climbing (the top of the free climbing scale). They were guided by the father-son team of Antonio and Angelo Dimai, with guest-star guide Angelo Dibona joining the team. Antonio’s two sons, Angelo and Guiseppe, and the Cortina guide Arturo Gasperi had previously climbed and pre-equipped the route with strategically placed pitons in preparation for Miriam’s arrival that season, and honoring Miriam by naming the climb the Via Miriam. A week later, Miriam climbed it with her team in 3.5 hours, falling a few times and weighting a piton at one point, and later devoting three gripping pages of detail of the difficulties in her autobiography.

In Italy, the route was celebrated and Miriam’s feature article appeared in the 1928 Rivista Mensile, the journal of the Italian Alpine Club. In Britain, the route was controversial—the style of Via Miriam was considered as merely ‘facilitated’ by ironmongery, lamenting how modern guide’s ‘mountaineering” skills had been replaced by piton-protected ‘acrobatism’, considered ‘more or less unjustifiable’. In contrast with the honored Antonio Dimai, considered “the finest cragsman in the Eastern Alps” (Strutt, 1941), and who reportedly only used pitons for belays in his long career, the Alpine Journal’s consideration of Antonio’s avant-garde sons was less flattering—they ‘inherited their father’s skill’ but failed to inherit ‘all of his methods’ (AJ1933).

Miriam had no such qualms about the new methods, and throughout her life, she was proud of the route named in her honor. For Miriam, it was her first direct exposure to the techniques that would soon also enable new bigwall standards in America. Her complex relationship with the ‘ethics’ and ‘morals’ of pitons, which she frequently shares in her writings, also begins. She continued to progress her skills with Angelo Dimai for many years, often leading crux pitches on routes new to both her and Angelo (a guide letting a client lead was rare—Antonio Dimai would always climb first, but “with Angelo I could lead all I liked, just so long as we were out of sight of his father”, Miriam writes). Her growing lead skills fueled her guideless and manless climbing goals, and she became known for decades as ‘America’s foremost woman climber’, as still noted in the March 1961 Summit Magazine.

French Alps

In her seasons on the Aiguilles of Chamonix, Miriam was no less accomplished, climbing many of the hardest alpine and rock routes in the Mont Blanc range. In 1926, she began with moderate guideless climbs with her brother Lincoln and others, noting, “I planned soon to do more and on a bigger scale,” and here in France, she also found the ‘right’ guide for her progression, Alfred Couttet, one of the early French guides to adopt pitons for harder routes. “Couttet was using pitons, and using them skilfully. But at the time he wished it kept a secret!” she writes. Couttet also broke guiding convention by seconding Miriam’s leads on hard climbs. In their second season together they climbed a long new route on the Aiguille de Roc du Grépon that involved twelve rappels to descend; it was an auspicious start to Miriam’s expansive repertoire of hard climbs in the Alps with and without guides, and many with other top women climbers of the day (footnote).

Footnote: In addition to famous more alpine climbs like the Matterhorn, Jungfrau and the Mönch (first ‘manless’ ascents), as well as endurance traverses, Miriam climbed the Western Alps rock testpieces like the Grepon multiple times by various routes—her famous ‘manless’ climb of the Grépon in 1929 with Jesse Whitehead and Alice Damesme (who led the Mummery crack on that occasion), though by no means her hardest climb, became globally known; her account was published in the August 1934 National Geographic magazine, no doubt patronizingly edited, or at least captioned: “A strong wind bothers a lady, though she has no skirt to worry about”, etc.— the many sexist comments that accompanied the press about her climbs are not included in this research, but they are easy to find. Likewise, there is not space to include some great epic tales like her attempt with Angelo on the Fehrmann route on Campanile Basso, where they had to sit out a gusting sleet storm on a 6” ledge, or of her travels and dreams in the Kaisergebirge and Julian Alps.

Swiss Alps

By 1930, Miriam was ready for her hardest climbs yet, long alpine rock routes in the Swiss Bernese Oberland following in the footsteps of Gertrude Bell. After a 19-hour ascent of the Dreieckhorn, she writes, “Why not repeat some more of her climbs, so engagingly described in The Letters of Gertrude Bell?” Here she found yet another guide, Alfred Rubi, who did not mind being second on the rope, and she often lead every pitch of long climbs of ‘great endurance and fortitude’. “I enjoyed climbing rapidly” she reflects in her autobiography, and indeed, many of her climbs broke records for the shortest time, a big advantage in the wild mountains where sudden weather changes are deadly. In succession, she climbed the Engelhörner, Wellingrat, and the third ascent of the NE ridge of the Finsteraahorn, which the previous ascensionists had noted, “A bivouac will always be necessary.” She and Rubi (with Rubi’s younger brother Fritz as porter) climbed the 1000m route in 13 hours, with a 7-hour descent, the first “one-day” ascent of the spectacular line. Of Miriam’s impressive resume of successful climbs, many would have been at a level of commitment as the career-best for most climbers of the day.

Complex Relationship

Miriam’s relationship with tools was complex; in her writings, she frequently makes attempts to explain the ‘morality’ of pitons—the line of acceptable use as they became adopted during her career as a climber. Of her early days (pre-1928), she writes of a climb that went awry, “Not one of us in those days would have stooped to carry a piton,” despite the fact that she had already climbed some very difficult piton-protected routes with guides by that time. Climbing without ‘artificial aids’ was the goal, and big routes like the north wall of Cima Una, an 800m route which she climbed with Antonio Dimai in seven hours in 1928, were climbed piton-free; she laments how subsequent climbers added many ‘unnecessary’ pitons, and ponders the balance between risk and skill, a central theme in all realms of climbing. In her later years, she writes,

“But the piton for security is something else. We have all heard younger climbers tell us, with impatience, that they do not use pitons to help them get up, but merely to make the climb safe, and that it is exactly the same climb it was before, only safer. It most definitely is not the same climb. These modern climbers are getting from their pitons enormous help without admitting or, perhaps, even realizing its extent. And in this, to my mind, lies the more questionable ethics of the piton.” (Miriam O’Brien Underhill, Ironmongery Then and Now, Yearbook of the Ladies Alpine Club (London), 1957.)

In the 1950s, when she wrote this, America was undergoing a big shift in technological climbing—reusable chromoly steel pitons were coming online, allowing a smaller rack for bigger climbs, and bigwalls like El Capitan were first being considered. “I have no quarrel whatever with direct-aid pitons,” she writes; her concern was for the adventure lost on overly protected free climbs: “It is not the same climb (with more pitons), because the piton removes or greatly mitigates the penalty for failure… For even if the modern climber never needs to use these pitons, they are there, removing from his mind a great weight of responsibility.” Her preservation of challenge argument with balanced risk would be closely repeated by older climbers when bolted sport climbs became a main game in the late 1980s in America, a time when the acceptable moderate use of bolts was closely defined and an oft-debated ‘rule of the game’.

In her early days, however, Miriam’s attitude toward pitons was softer. In 1931, she recognizes the standards of difficulty are higher than in the 1920s due to “recent developments in rock climbing technique and skill” and writes, ”The raising over the years of standards of difficulty is due in large measure to the use of improved equipment, and particularly of pitons.” This was a period of rapid expansion of piton-protected climbs in Europe, which was followed by a similar wave in America a few years later. She comments on how Armand Charlet, a critic of pitons except for roping down, had no qualms about leaving his jammed ice axe in cracks to protect difficult sections. “Morally, I see little difference between using a piton and jamming in the ice axe.”

But it was not just hardware that Miriam adopted as she became America’s leading rock climbing maestro. She learned from the best and holistically understood the new climbing systems. Of potentially catching a fall on a climb in France in 1926, she writes, “the chief rule is: don’t try to stop the fall abruptly but let the rope run a bit and brake it gradually”, perhaps the most succinct explanation of a dynamic belay until Richard Leonard’s analysis in Belaying the Leader (1946). She also developed nuanced skills in using carabiners and slings, as evidenced by the impeccable teamwork with her partners, especially on her efficient ‘manless’ alpine ascents. She understood the advantages of longer ropes, sometimes equipping 150-foot ropes for certain climbs in a time when much shorter ropes were ‘normal’. And she was an expert in rock climbing footwear, the scarpa da gatto, shoes with layers of woolen cloth or rope soles (‘best when old and therefore well-conditioned’), and the trade-offs with the rubber soles of ‘sneakers’ also becoming popular around this time.

All this information Miriam would bring back to the USA after each summer season in the Alps, where she climbed on the many local crags of the East Coast, where almost certainly, these new techniques were first practiced. But it was her on-and-off early climbing partner and future husband, Robert Underhill (whose breadth and depth of experience on cutting-edge routes in the Alps was much more limited), who became the main spokesperson for the new tools and techniques in the early 1930s (footnote). In this early period, at the height of her rock climbing career, Miriam was content just to write about her experiences, and avoid the ethical dilemmas that came with exposing the new tools and techniques. Miriam also became an expert skier and continued climbing throughout her whole life, with many productive climbing trips to Europe and the American West, including new routes in the Sawtooths (Idaho) and the Beartooths and Mission Ranges (Montana).

Footnote: Underhill was not the first to expose the new techniques, however, see Dean Peabody, On Belaying, Appalachia 1930. In 1931, Underhill published an eight-page treatise on rope techniques in the Sierra Club Bulletin (California) elaborately explaining how persons A, B, and C might make their way safely up a mountain with ‘legitimate’ use of the rope, and with instructive photos on various body belay methods (and perhaps the first expose on the use of slings). In the 1932 Canadian Alpine Journal, Underhill provides photos of the new hardware (pitons and carabiners), as well as the best sources of mail-order supply. But by 1932, the cat was already out of the bag (see Sturmia’s much more detailed 1932 article). In his travels he was also influential—Bestor Robinson credits Underhill's influence on California rock climbing in a 1934 Sierra Club Bulletin article: "The seed of the lore of pitons, carabiners, rope-downs, belays, rope traverses, and two-man stands was sown in California in 1931 by Robert L. M. Underhill, a member of the Appalachian Mountain Club, with considerable experience in the Alps.” In 1933 Underhill also published “The Technique of Rock Climbing” in Appalachia, of which he was the editor. Underhill’s note in 1932 CAJ: “The modern piton has been developed by the Germans and Austrians, and taken over from them by the Italians in the Dolomites and, in some degree, by the Swiss. It is best and most cheaply purchased in Munich and Vienna.Reliable dealers are: Sporthaus Schuster, Rosenstrasse 6, Munich, and Mizzi Langer-Kauba, Kaiserstrasse 15, Vienna VII. Illustrated catalogs are obtainable from each a summer catalog of mountaineering equipment (and a winter one for skiing). The pitons sold in France and for the most part in Switzerland are still much too long and heavy, and not of the best model (the Fiechtlhaken).”

East Coast ‘Great Leap’ continued…

As more climbers like Miriam returned from Europe after climbing the latest testpieces in the Dolomites and Chamonix, a steady stream of the new climbing tools and techniques began filtering west to the USA; the new means and methods of ascent would soon become standard in America. It is probable that European pitons were being used on the big routes of the East Coast as early as 1928 (footnote), a year when many of the tallest cliffs were first climbed, many by Robert Underhill, a professor of philosophy at Harvard from a Quaker family whose legacy has recently decomposed by anti-semitic views he shared. Disclosure of piton use was kept discreet until the early 1930s, but likely they were acceptably being used as described by Lincoln O’Brien in the 1927 Harvard Mountaineering Journal—as belays or for the descent. And as more Eastern Alp “Grade VI” climbers arrived in the USA like Fritz Weissner in 1929 who quickly established new standards of difficulty, the new game was on. Bill House, Robert Ormes, Glen Dawson, and Percy Olton also became prolific in climbing cutting-edge first ascents using (and developing) the latest tools and techniques in the 1930s period.

Footnote: In addition to the second ascent of The Pinnacle in Huntington Ravine described earlier, the “grim titanic guardian” Wallface in the Adirondacks, steep long climbs on Katahdin, the pink granite walls of Mount Desert, and south wall of Willard, were all climbed for the first time in this period. The first pitons on a long climb in the East Coast might have been on Whitehorse Ledges in 1927.

The history of East Coast climbing is well documented in Yankee Rock and Ice, by Laura and Guy Waterman (1993, reprinted 2019) so will not be covered here, but we’ll end this chapter with the line of the first ascent of the East Coast’s most prestigious bigwall, Cannon Cliff. No steel pitons were acknowledged but a makeshift wood piton for a wider crack (in contrast to the only thin metal pitons available at that time) was noted as used as an aid to overcome a difficult section. In terms of technical climbing when Old Cannon was first climbed, the USA was about three decades behind Europe. But within a single decade, the art-of-the-states caught up to the international state-of-the-art, and the significant new American bigwall climbs of the 1930s will be covered next.

Postscript

If you have read this far, I’d probably agree that it has been a long explanation of how new games with new tools begins in the late 1920s in America— really the story of how the attitude about pitons softened in the USA, as compared to no softening in the UK. To sum up: we have clear evidence of a bold and talented woman who starts climbing in the 1920s and becomes the most accomplished American climber on steep vertical climbs in the Alps. It takes place in an era when fascist attitudes were on the rise, especially among men, amidst a proliferation of propaganda films produced with new portable movie cameras (Bergfilm) glorifying the manly conquest of mountains’ virginity. The English literature is filled with highly critical and mocking accounts of Eastern European climbers and their climbs, mostly imagined as “steeplejacking” and not climbing. Meanwhile, under the radar, a group of talented women, most rarely mentioned in most historical timelines despite being highly respected by their close peers at the time, quietly climbing top-level cutting-edge climbs and reporting with objective and humble accounts. Sensing the trend in Europe, a group of American women lead the way by becoming top-level steep rock and alpine climbers, gaining extensive experience leading with the new tools and techniques, first learning from the best, then bringing that experience back to the USA. Miriam O’Brien’s boyfriend and later husband, Robert Underhill, widely publishes the “beta” and historically is credited with being the forerunner of the new standards despite having a much more limited experience and knowledge of the new systems (footnote). A deeper dive into the primary sources, combined with a broader understanding of global climbing trends and attitudes, and a more vibrant story of the adoption of the new tools in the USA emerges.

John Middendorf Winter Solstice, 2022

Thanks to Eric Doub and Sallie Greenwood for editing help (1/2023)—a few more bits to do.

Footnote: on Underhill contributions to the knowledge base. It is likely that body belay and abseil techniques were already known and developed in Colorado prior to Underhill’s publication of articles with photographs describing the techniques, starting with 1928 AMC journal. His published articles, which mostly described techniques from the European Alps, helped expand awareness, especially in California where ropes had mostly been used to safeguard short airy traverses in the Sierras with simpler rope bracing techniques. Regarding innovators who advanced rope systems in North America, Richard Leonard in California significantly brought new concepts and science to the art in the 1930s. Summary of Underhill’s earlier expository writings below:

1928: Underhill On Roping Down, June 1928 AMC journal. Hip and Shoulder Belay and descent methods directly imported from Europe. 5/16” rope slings and welded rings recommended for rappels. Whymper’s rope retrieval methods (always a bit theoretical and obsolete by that time) were described and illustrated. The purpose of a “snap-ring” described to connect two ropes around a wide boulder in lieu of a knot.

June 1930 AMC Journal: Underhill, On Artificial Aids in Climbing. “Ethical problems” discussed. On “whether it is proper to drive an iron spike of piton into a local cliff”. Justifies pitons for security as “Any aid which involves and requires a technique of its own is per se legitimate.” But pitons for aid not, as there is “no new technique” in doing using a piton as a hand- or foothold (?).

1931: Sierra Club Bulletin’s famous Underhill article “On the Use and Management of the Rope in Rock Work”—defining the “legitimate use of the rope”. No mention of pitons even though they had been used on his ascent of Mt. Whitney that same year. Again, a revision of belay and descent ideas imported from Europe, some ideas border lining on the theoretical.

1932: CAJ article, “Modern Rock Climbing Equipment”, piton and piton hammers introduced. Very limited in breadth, especially compared to Max Strumia’s article Helps to Climbers published in the AAJ the same year.

December 1933 AMC Bulletin, The Technique of Rock Climbing, Part 1, General Principles—mostly on the physical movement on rock and psychological difficulties. “We feel lost and helpless upon a great rock wall, unable to deal with it satisfactorily, anything but its master. And the remedy for this lies in becoming its master.” Part II covered The Climbing Hold over ten pages.

Appendix/Bigwall scrapbook

Huntington Ravine

Personal stories like this will appear in the next bits, as they are fond memories of the same climbs I am researching…