Trango 1987(b)-3rd ascent Trango Tower

Trango History Series by John Middendorf

In 1987, remote big walls were coming of age—bold new lines up unclimbed walls in Patagonia, Baffin, Himalaya, and the Karakoram became objectives with varied styles, first practiced and mastered in local training grounds like Yosemite and the Alps.

Alps, 1980s.

In terms of training grounds for hard bigwall routes like those in the Trango Towers, in the 1980s Chamonix was one of the world’s great locales—plenty of climbing partners and cheap living in Snell’s field (closed in 1991) brought comers from all over the world, and every season natural climbing lines were envisioned and weaved between the classic bigwall routes of the prior era. Free climbing was of the highest standards, but the stigma of every move needing to be ‘free’ was often preceded by a style that preferred efficiency over the eventual rating. Some called the style “French free” which occasionally involved pulling or stepping on gear for short sections, but mostly boldly climbing in rock boots with clean climbing gear, the limits ever-expanding each year with improving skills and tools—ever more precise ranges of camming devices and small nuts that could be wedged in natural cracks of all sizes and shapes. Hammered-in pitons and sometimes bolts were also used for these first ascents, and generally left fixed in place for future parties following without a hammer, This pragmatic style was well-suited to the region's unpredictable weather and short windows of opportunity for climbing between storms, and leading practitioners were creating elegant and fun lines that could be climbed fast and light. In 1985, Mountain Magazine called the style the “modern idiom” of hard rock routes and noted activists such as the Swiss guide Michel Piola as “the most prolific pioneer’ on the Chamonix granite, and known for his ‘eye-for-a-line’ (as well as the skills to climb them).

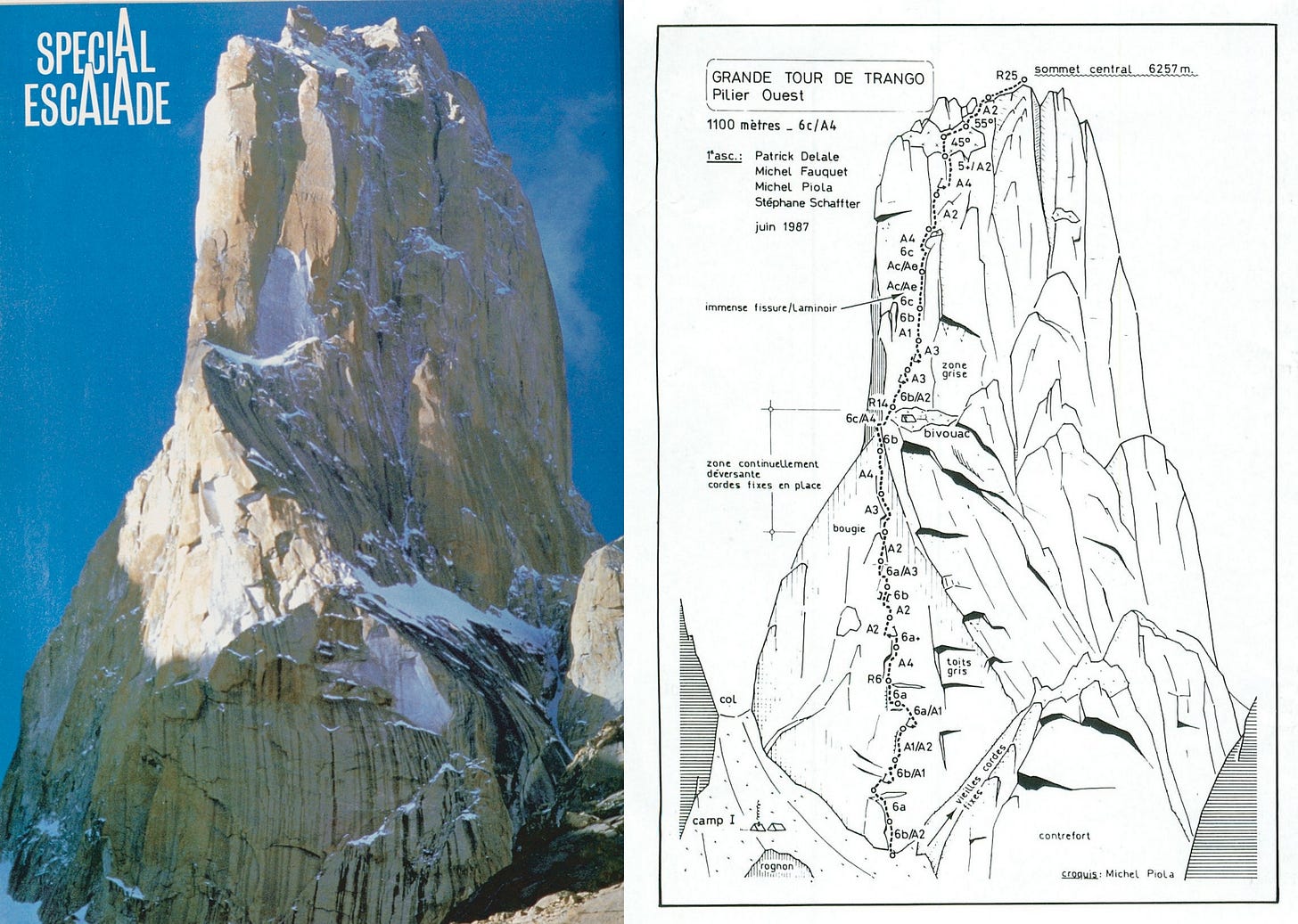

Topos

Not only was Piola eyeing and climbing aesthetic lines of travel up the granite walls, but he was also the leading topo artist of the era. His guidebooks such as his Le Topo du massif du Mont-Blanc guide published in 1985 inspired a whole generation of climbers who could imagine the pitch-by-pitch climbing with a line illustration overlaid on a sketch of the feature, much better than the written descriptions of earlier guides. The guides and topos helped foster a new breed of popular ‘classics’ on the rock towers of Chamonix.

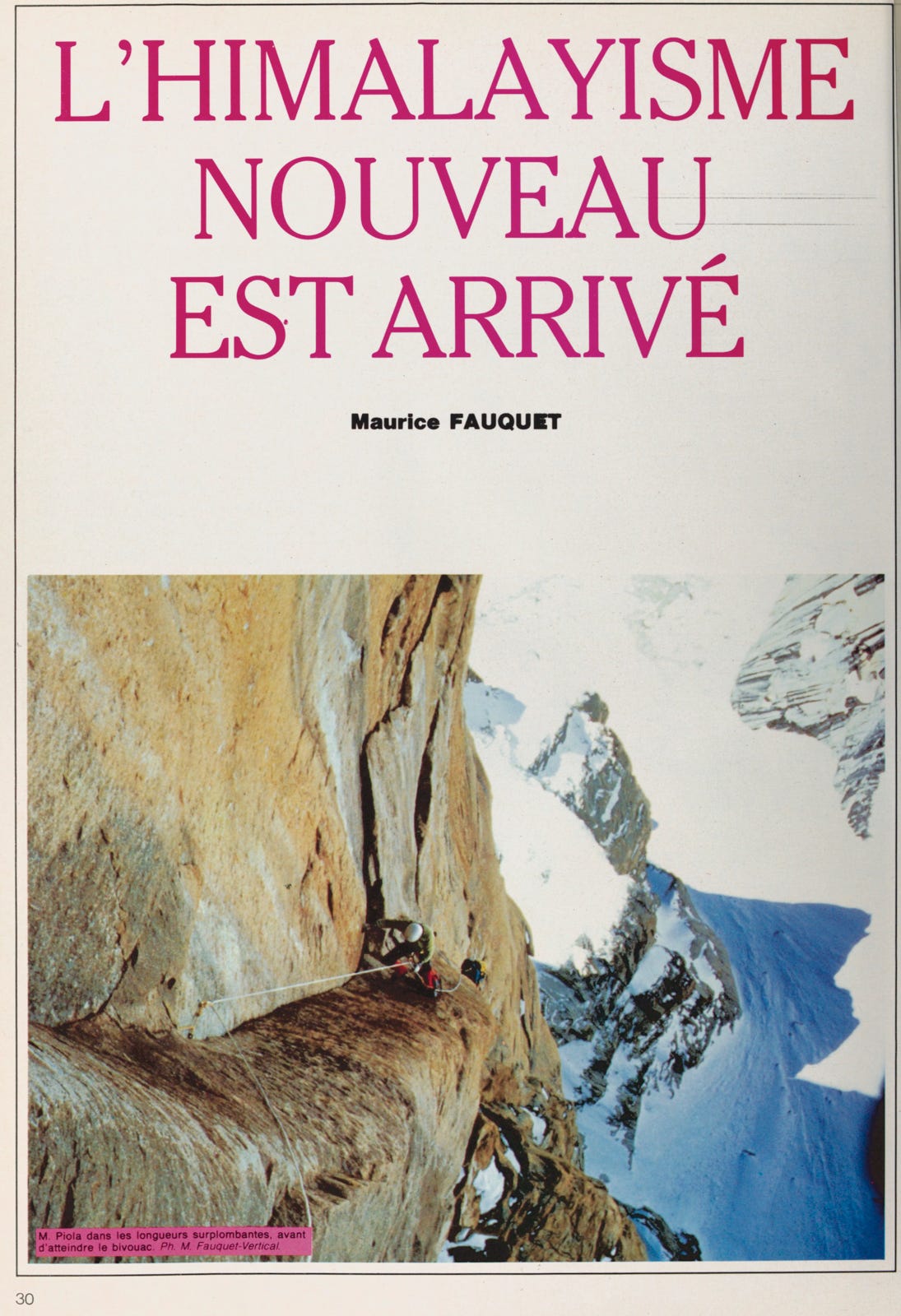

Danse Trango

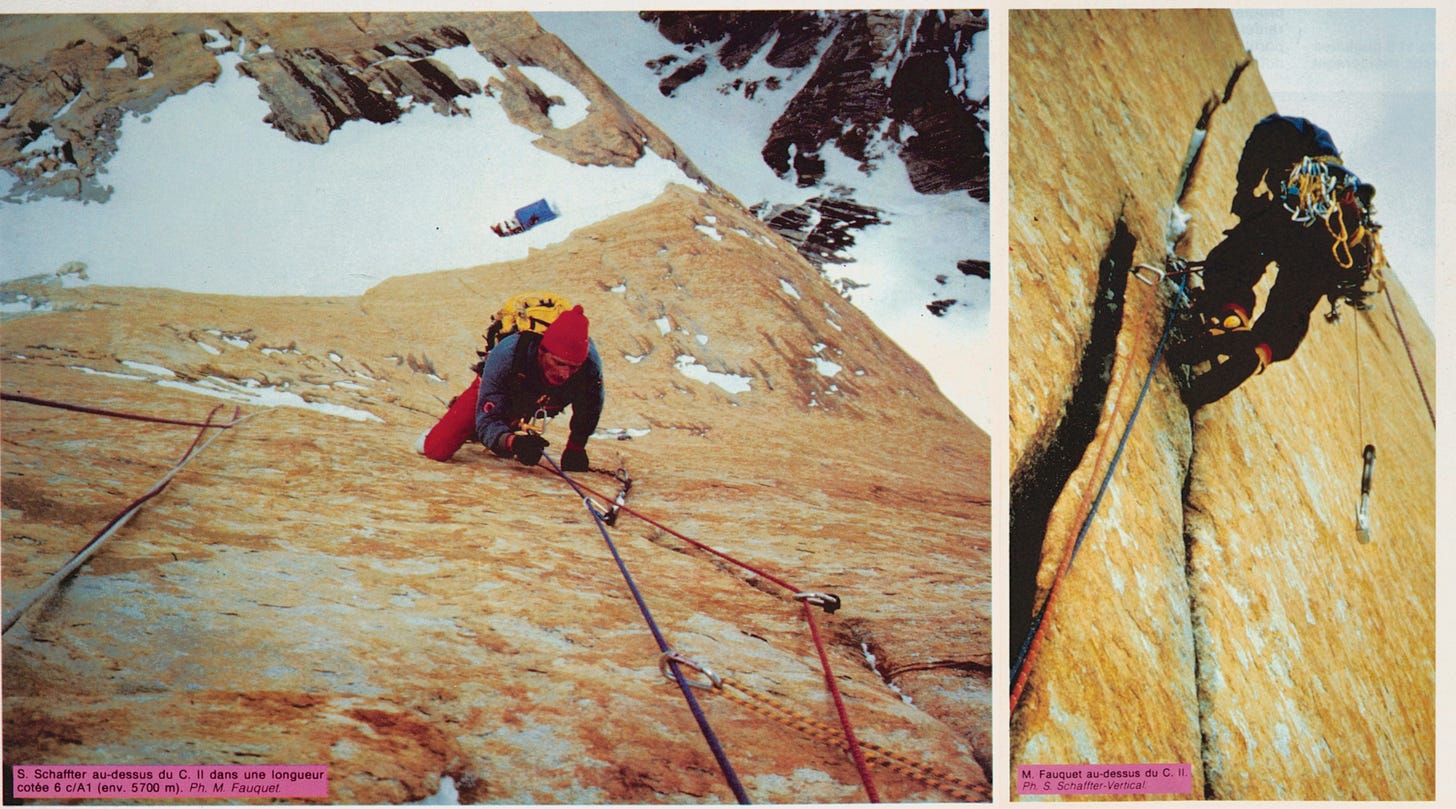

In 1987, Piola joined the Franco/Swiss expedition to Trango, to first climb the west wall of Trango Tower, an imposing overhanging buttress no one had yet attempted. The team included two highly experienced Himalayan and Karakoram climbers and guides, Stéphane Schaffter (Club Alpin Suisse), and Michel Fauquet (Club Alpin Français), who had both planned Himalayan/Karakoram double-headers that season—to climb an 8000m peak and a new route on Trango Tower, between attempts of the south face of Lhotse and Makalu. Patrick Delale, who with Schaffter had experience on technical walls in Peru, and Piola traveled to Skardu where they met the two seasoned Himalayan climbers on May 24.

The expedition was a three-sport adventure: mountain bikes for the approach, climbing gear for the wall, and a parapente for the descent. Mountain bikes at the time were in their infancy (hardtails and hard fronts, too), and were ridden on the approach to the Baltoro Glacier. Back then it was a three-day trek along the steep sides of the Braldu River from the closest road in Dasso to Askole, with steep but well-trodden paths between villages, and from there another three days to the Baltoro Glacier.

The line

In his article Danse Trango in Mountain Magazine reporting of the Franco/Swiss ascent of Trango Tower in 1987, Piola notes the tactics as ‘bigwall climbing California style’, where the eye for an aesthetic line, linking natural features, is a core skillset of the style. Fauquet, too, had bold visions of the possible; his bold attempt on the Ogre in 1983 was legendary—as a team of two, with Vincent Fine they climbed 900m of the difficult south pillar of the Ogre using modern aid techniques amidst hard free climbing, 24 pitches in 5 days with hanging bivouacs and no fixed safety rope to the ground—a committing effort and one of the boldest alpine bigwall forays at the time. Storms prevented the final 200m to the summit, but the attempt opened eyes to a new level of alpinism that wasn’t matched for some years.

The west buttress of Trango is steep and long (1100m), with the difficulties beginning much closer to the Trango Glacier than the British and Slovene route, the latter being climbed at the same time from the Dunge Glacier—see this post). The initial shield of the west buttress is overhanging and fractured, and picking out a safe and elegant line was the first order of study. The plan was to climb and fix ropes through this shield up to the first natural ledges on the route, 600m up, followed by an uncertain link to a crack system on the upper headwall, and from there go fast and light to the summit.

Piola explains the strategy in Mountain 119, “We split the team as follows: Stéphane with Tchouky, Patrick and myself. The two teams worked together better and better as the expedition progressed, alternating days on the mountain fixing the route and then resting.” After five weeks of hard climbing and hauling, the ropes were eventually in place and anchored above the lower wall’s final overhanging pitches, and Camp Two was set up on the snow ledges above. After a false start requiring descending and reascending the fixed ropes from basecamp, and a few days rest in between, on June 22 the team began a final two-day light and fast climb up through the final headwall, which began as a knifeblade crack and widened to an offwidth chimney. The summit reached, they found no sign of the Slovene team’s ascent who had been there a week before, and set up for their third “first world’s record” (Bal à Trango), a paragliding flight from the summit of Trango Tower.

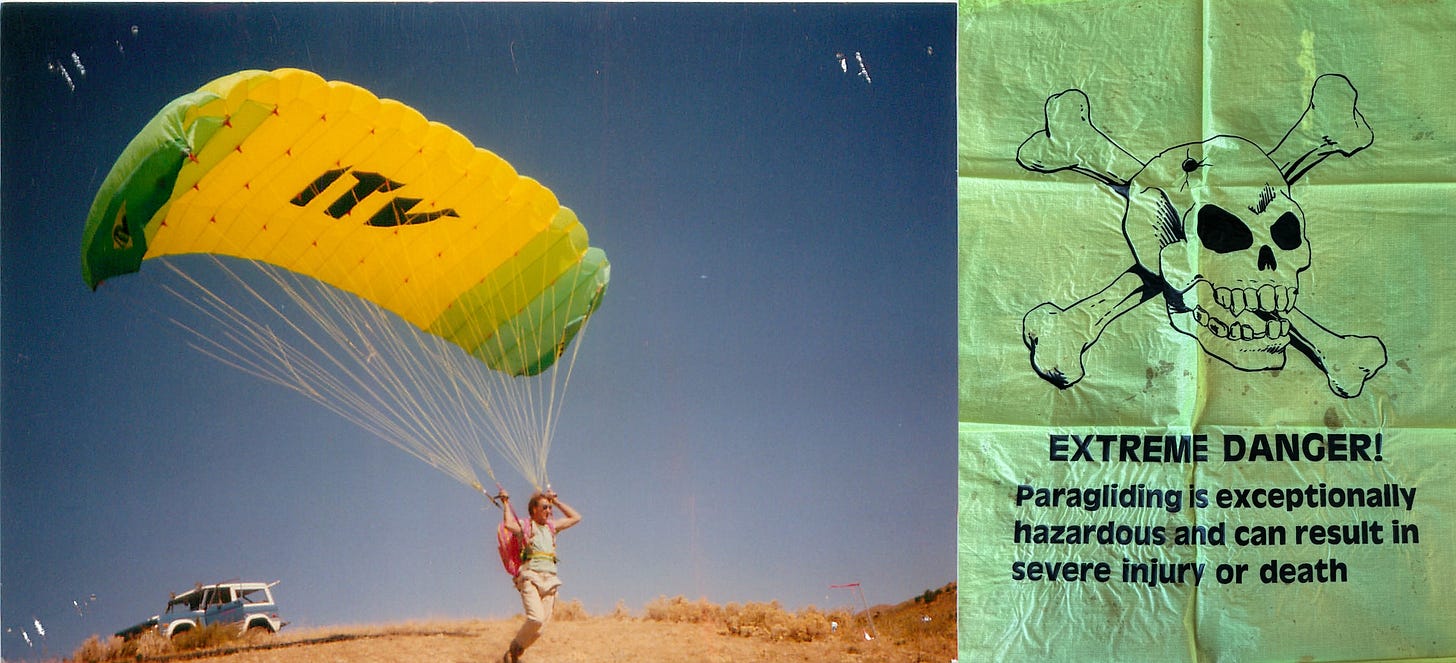

Parapente technology, 1987

Like mountain biking, in 1987 paragliding was in its infancy. People had been foot-launching skydiving parachutes for over a decade, but in the mid-1980s, new parapente-specific designs became available. The first production designs were square canopies, like skydiving parachutes, but without the need to withstand the high shock forces using new lightweight non-porous fabrics, stiffer lines, and cell openings designed to enable easier launching from a running start. These first-generation parapentes generally had 7-cell or 9-cell openings, a low stall speed, and terrible glide performance (3:1 touted, but generally less). Cliff launching these early wings usually meant a drop of a dozen meters before actual flight began, but the advantage of the simple square design with large ram-air openings is that these early wings generally did not stall or collapse during low-wind, short take-off, cliff launches.

With Chamonix as the epicenter, with its easy teleferique rides to launch sites, incredible feats were made possible with the new descent tool. People were climbing Mont Blanc in hours and descending in minutes. In March 1986, Jean-Marc Boivin climbed four north walls one winter day: Aiguille Verte (2hrs), Les Droites(3.5hrs), Des Cortes(2.5hrs), and finishing with the Shroud on the Grandes Jorasses(6.5hrs), with quick paragliding descents between each climb, landing in Chamonix at 10:30pm, less than a 18-hour round trip. Christophe Profit descended from the Walker Spur with a paraglider for a winter solo trilogy in 1987 that included the north walls of the Eiger and the Matterhorn, and would later become the first to paraglide from Everest in 1988. These early wings were touted, and well used, as climbing descent vehicles, and amidst a lot of accidents, climbers were extending their potential to launch from tight summits.

[The original simple designs began evolving into higher performance elliptical designs in 1989 when competition began and paragliding boomed as a sport. The second-generation wings (1989)were larger and had more cells, and were not as suitable for low-wind, short take-off cliff launches due to a higher stall speed, and more lines to evenly load.

First paraglider descent, Trango Tower 1987

For the expedition’s goal of a third “world’s first” (in addition to mountain biking and climbing), once on the summit of Trango Tower, Michel Fauquet prepared a launch site on the west shoulder, and with Piola and Delale holding the wing in position, he took a few strides in the light evening breeze and launched over the cliff; ten minutes later, 2000m lower, he landed in basecamp, proving that from even the world’s tallest and high-altitude rocky tower could be flown and descended by paraglider. It was a bigwall climber’s dream come true. The rest of the team descended by rappel over two days, removing most of the fixed ropes. After a four-day trek, the team returned to Islamabad with its endless expedition paperwork requirements, celebrating their first ascent on Trango Tower and a fantastic adventure.

Authors Note: I was also trying to find the launch limits of these early paragliders. John Bouchard was importing ones made in France to the USA under the brand ‘Feral’, and I was the recipient of one of the first four he brought to America. After a couple of days of frustrating ground handling in strong winds in Bishop, California, my very first flight was a 2000-foot cliff launch in Baffin Island in 1986. It was an exciting start, and I continued to push my limits of cliff launching with the idea that one day I would use my paraglider to descend from a remote bigwall. My best cliff launch was from the Moki Dugway in Utah, which involved pulling the glider overhead in a light wind followed by a step off the edge of a 300m cliff (boldly or foolhardily uncertain).

Postscript notes:

From Alpinist 11 (Michel Piola, translated from the French by Eric Bye): A brief reflection on the real or relative commitment of a big wall, wherever it's located in the world. I have always been convinced that total commitment has to be seen more in light of a team's reduced size (two people) and a climb's remoteness rather than a chosen style of ascent. In fact, a rock wall is never committing per se, even on the Trango Towers; by definition descent is always possible by rappelling. So it's the ascent and the effort as a pair (rather than as a team of four with alternating days of action and rest), it's the moral responsibility and the difficulties of escaping a bad spot or ensuring an evacuation that define the commitment.

Also, the tendency to discriminate, even for a "light" roped party, against a method that uses a few fixed ropes at the bottom of a wall, is incomprehensible to me! My experiences have shown me that lighter is always quicker. This formula is one I've arrived at by way of some epic nonstop assaults on summits without bivouac equipment; it's quicker than the more generally adopted capsule style, a technique I have also tried and one that is, in fact, often more comfortable. But doing big walls surpasses this little quarrel of styles, for climbing these walls represents an art of living fully that improves everyone and that you practice as close as possible to your dreams, your courage and your passion.

Second Ascent, 2006 report (Lindsay Griffin): Gran Diedre Desplomado (VI 5.11 A4, 1100m, Delale-Schaffter-Fauquet-Piola, 1987). In July, the Swiss team of Francesco Pellanda, Giovanni Quirici and Christophe Steck, accompanied by photographer Evrard Wendenbaum, made the second ascent of the route, freeing all but three pitches. After twelve days' work, and five nights on the wall, the Swiss reached the summit on August 2. Though they had completed the route's second ascent, they had used aid on pitches 13 (A4), 15 (A3) and 16 (A3). They estimate the 13th pitch would go completely free at around 5.13b. It is notable that despite the efforts of some of the world's best climbers, the Tower continues to put up a stiff challenge. This route involves considerable amounts of hard aid climbing, more or less confirmed by the highly experienced Spanish big-wall climber Alfredo Mandinabeita, who attempted the second ascent of the route, solo, to half height in 2004.

More Trango Tower history series by John Middendorf:

Trango Towers chronology of climbs

Minamiura’s Solo of Trango, 1990

Trango 1988a—Geology of the region

Trango 1988b—Kurtyka-Loretan

Trango 1988 sidebar—meeting Erhard Loretan

Trango 1987a: —The Slovene Route (1987)

What’s in a name?—Trango—history of the mapping and naming of Trango Towers

Trango 1987c: Le Trango Château (Castle)

Trango 1987b-3rd ascent Trango Tower (this post)