Tita Piaz, PartD--Big Wall Climber

Mechanical Advantage #9d

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Footnote: Often histories credit Hans Dülfer (1892-1915) for the first rope maneuvering and descent techniques, most notably the evolution from his methods now known as the “Dülfersitz”, the standard way of rappelling even in my early days of climbing (1970’s). But it’s pretty clear that Piaz was the originator of high angle rope gymnastics, combining bold free climbing and rope systems to fly across and up elevated slabs of rock. The Piazwand on the Totenkirchl, first climbed in 1908 and later rope-soloed in 1911 by Preuss, was the first route up a major unclimbed wall that really put all the new techniques into place, creating a new visibility about what was possible on the largest rock walls on Earth.

Totenkirchl

In 1924, Franz Nieberl, climber and stellar chronicler of climbing techniques, recounted a dream he had in the Kaisergebirge twelve years prior, at the base of the Totenkirchl, prior to Hans Dülfer’s breakthrough ascent of the direct west wall. In his dream, the spirit of the Totenkirchl came to life and told its story, how it first formed in a primeval sea, then born to the world as a giant limestone tower with steep walls on all sides, where it was “enthroned, secluded and undisturbed” for eons. Then, the “little human beings” arrived and began sneaking around its base, then climbing its faces with wall hooks and complete “locksmith’s shops” in their pockets (most gear was carried in jacket pockets back then, rather than on slings with carabiners). For a while, only three of its four mighty walls were climbed, and the spirit of Totenkirchl was confident that its west wall, “the one as if made from one piece”, was its trump card, safe from the “tiny tough tormentors”. But then a “skinny human child” arrives with a giant snake of Manila hemp braid, and with piton on piton perilously descends the west wall’s overhangs and chasms. With its face defiled, the “carefully fooled” wall was soon ascended and removed from the list of impossible climbs. The spirit concludes, “Now I was worn out. The old song rang out again: this is the hardest Kaiser tower!”

The Totenkirchl is a striking stone monolith in the Kaisergebirge, a low alp (~2500m) region about 100 kilometers south of Münich, and one of three major mountain ranges (along with the Wetterstein and Karwendel ranges) that comprise a long east to west chain of limestone and dolomite peaks as the centerpieces of North Tyrol. The word Totenkirchl translates to “Church of the Dead”, named after small churches in Eastern Orthodox Christian areas that sometimes house mummified bodies, and from a distance it is an imposing feature on the landscape. Even though the Eastern Alps ranges were primarily within Austria-Hungary at the time, the northern climbing ranges were considered the domain of the German-speaking “Münich School” climbers, notably Kaiser guidebook author Georg Leuchs and others, and the southern Tyrol climbers rarely visited. Tita Piaz was an exception.

West Wall of the Totenkirchl first ascent, 1908

The west wall of Totenkirchl was for many years, “the last great problem” of the Eastern Alps, and several top climbers had attempted forays up the wall in search of a climbable route. Pitons were just starting to become mainstream tools, still only custom made in small blacksmith shops, and in their infancy mostly used as a point of direct aid or as belay/rappel anchor. The concept of difficult free climbing above a piton, tempting a longer shock load fall, was still highly feared, and Piaz was well-known as the boldest in this art. With his extensive experience of rigging ropes safely for Tyroleans and rappels, maneuvering to gain features both while ascending and descending the complex spires of the Dolomites, he was ready to lead the first of many big wall breakthroughs in the Alps, now made possible with stronger and lighter rope and piton systems.

Many great climbing adventures begin on motorcycles, and Tita’s epic 300km trip from Perra to Kufstein was one of the first on new roadways connecting the Tyrol regions, and with one of the first factory-produced touring motorcycles, which only appeared around 1901. He motored up to the North Tyrol with Franz Schroffenegger, a Tiers mountain guide of repute, and there they joined the rest of the team with the objective of climbing the first ascent of the west wall of the Totenkirchl.

A meeting of north and south Tyrol tribes, the other two members of the team were Josef Klammer, an experienced alpinist and founder of the first mountain rescue team from Kufstein, and Rudolf Scheitzold from Munich, who had made a committing abseil descent of the wall from its second terrace the year before (referenced in Nieberl’s dream). Although Schietzold’s inspection of the route revealed a few secrets about the possibility of a climbing route up the west wall, he initially reported it “impossible” and warned against any attempt. Piaz was soon introduced to the community, including the president of the DÖAV section, Anton Karg by Franz Nieberl, who joked (according to Piaz), “Mr. President, what to you think of these very modern guides, who travel 300km on a motorbike to try the biggest problem of the Eastern Alps? You can rest assured that Piaz will teach Latin to our Kaiser climbers.” Soon the team began their 16km trek from Kufsein to Hinterbärenbad, where the Totenkirchl dominates the view.

One of the key skills Piaz brought to the table, based on his extensive first ascent experience in the southern ranges, was his eye for a line, knowing the limits of possibility with the equipment gathered for the ascent. Piaz writes, “At a glance I was surprised the (west wall of the Totenkirchl) had not yet been won, and I did not even have a flash of doubt that the attempt would not be in vain.” Exploring the wall with binoculars, he immediately saw the precise line, and writes of his explanation, “Do you see the little wall on the right, with a crack barely noticeable on the left? Well, I tell you we will pass by there, and I promise, if we do not, then I will become a barefoot friar.” And sure enough, the line that Piaz had envisioned from below had been the climbable line of weakness, a discovery unknown to all previous attempts. The key free-climbing pitch that Piaz had scoped was soon named the Parete Piaz and immediately became legend in the climbing world as a feared run-out crux, about 5.7 or 5.8 (in German, the ‘Piaz-Wandl’).

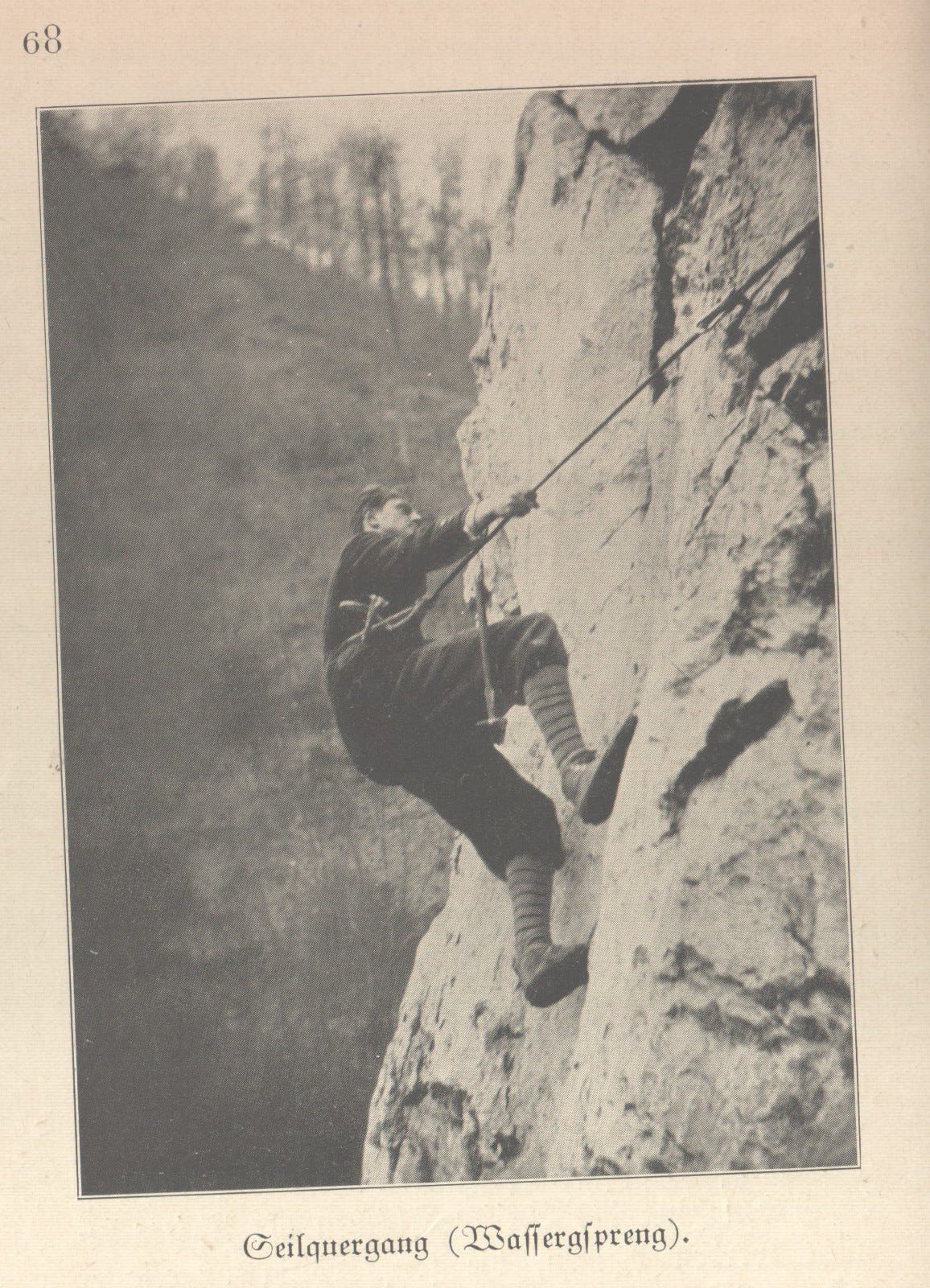

The “Rope Crossing”

The route was not entirely free. A shoulder stand was rumoured, and the route was reported as having, “many pitons, mostly only used for security purposes.” One of the keys to the route was a roped tension traverse. The Piaz team described this pitch as “30m long traverse up and left, then falling sharply downwards (wall hook) left into the chimney”. Though Piaz himself preferred to focus more on the free-climbing difficulty of the “Parete Piaz” in his recounting of the climb, Fritz Schmitt describes the section as a “delicate point with twice diagonal abseiling, jammed ropes were extremely malicious, a few steps on a smooth wall, and I was safe in the chimney. But what does it mean to be secure in a 120m chimney with all kinds of overhangs, chockstones, and smooth cracks?” (1934 SAC). Subsequent reports of rope tension techniques on other routes during this period are often similarily awkwardly described, and it is not until the late 1920s that this technique, of using the rope and anchor system to move laterally on a wall, becomes universally identified as the “Seilquergang” (‘rope traverse’ or ‘rope crossing’) technique.

Despite the warnings by the first ascensionists that “repetitions are not recommended for this route” due to its difficulty and danger, the west wall of the Totenkirchl quickly became a sought-after technical and mostly-free big wall route, with over 30 successful ascents in the following five years, as well as many attempts and even a fatal accident (Leuchs, 1917). Despite technically harder and longer routes established in this period, the PiazWand, as the route became to be known, reigned supreme in the literature as the testpiece wall, until the advent of Dülfer’s more direct route up the west wall of the Totenkirchl in 1913, which established yet another new yardstick of visionary lines. In Piaz’s telling of his adventurous climb, he concludes, “Four years later (actually 5), the great Dulfer, in the company of his friend redwiz (sic), corrected the wall with his memorable direct.”

The 1908 traverse on the Totenkirchl is the first example of a rope tension-traverse being a key to a significant big wall breakthrough. The dependence of the rope with a distant anchor, hanging and swinging around on airy rock walls can be daunting even for modern experienced climbers. As more optimal natural-fibre climbing rope knowledge improved among climbers in the first decade of the 20th century (see ropes article), the idea of using the rope and anchor systems as a way to maneuver laterally on big walls to connect natural features shifted from the fear of a death sentence with fragile ropes and insecure anchors, to a mainstream climbing technique even in exposed and overhanging climbing situations. Over the next decades, the technique evolved and was used on many alpine and big wall breakthroughs on even the most fearsome high alpine walls in the Western Alps, including the first ascent of the North Face of the Matterhorn by the brothers Franz and Toni Schmid in 1931 (footnote).

Footnotes: The 1908 route on the Totenkirchl only got a brief mention in the 1910 DuÖAV journal, but a full route description appears in the XIII Jahresbericht for 1908, Alpenverein Sektion Bayerland (1909). Although the rope traverse section was later free climbed without rope tension (possibly by Paul Preuss in 1911), many still depended on tension with the rope for the traverse into the exit chimneys even into the 1970s (see 1978 DAV topo below).

Other climbers at the time were also starting to experiment with tension traverses, mostly on smaller crags, and prior to Dülfer’s short-lived technique of bringing a completely separate rope for self-belayed tension traverses, employed on his 1912 ascent of the east wall of the Fleischbank, ever more difficult tension traverses were established on new routes, notably by Angelo Dibona on the Laliderer in 1911 and Georg Sixt on their climbs. Hans Fiechtl and Otto Herzog famously introduced the carabiner to the technique on the Schüsselkarspitze in 1913. Beginning in the 1920s, the Seilquergang was illustrated and described in many journals. Karl Prusik wrote a book on techniques in 1929 and considered it one of six basic techniques that should be formally taught to every beginner climber (along with knots, belaying, rappelling, hauling a pack, and creating an anchor with pitons). Note: the evolution of gear and techniques in pre-WWI years will continue in more detail in this series, setting up for the explosion of harder big wall routes in the 1920s and 1930s in the Eastern Alps and eventually throughout the world.

Author note: after completing a pendulum on the first ascent of Kali Yuga on the northwest face of Half Dome in Yosemite, I jokingly suggested a new rating system for such big wall maneuvers, rating that one P4, as it was a very difficult traverse on the overhanging wall leading to a very tenuous series of moves to gain another crack system far to the right. With this scale, the flexing knifeblade anchor for the Nothing Atolls pendulum on the Pacific Ocean wall would be considered P2. But despite the skill and fear needed for safely overcoming such maneuvers, thankfully there has never been need for an additional rating system for pendulums. (Early tension traverse/pendulum illustrations below).

Thank you and goodbye for now, Mr. Piaz

Having considered these early contributions by Piaz to the techniques and limits of rock climbing by 1908, we leave Piaz here, though by no means were his contributions over; he continued to establish cutting edge ascents using the latest tools and techniques of climbing throughout his long and adventurous career, and a whole book could be written on his family life, theatre career, military service, and civic involvement. He built rufugios and brought many to the mountains for the first time, and his work in the rescue field was no doubt remarkable. Piaz climbed with kings (Albert I of Belgium), and shared his knowledge with so many of the pioneering climbers of the era. The Austrian Conrad Kain climbed the Marmolada with Piaz, calling it “the most arduous tour I ever made”, and soon after moved to the Rockies and established the hardest climbs in the Bugaboos and other new realms where big walls were first becoming accessible. For a climber, Piaz’s soloing, bold free climbing, speed climbs and enchainments, big walls, complex rescue rigging, and professional guiding techniques are truly remarkable in their pioneering spirit.

Next: Dibona, Dülfer and other pre-WWI developments.

Topos:

LINKS

In the Beginning: Subtle Means and Engines

The Modern Era of Mountaineering (1786)

American Trail Builders, 1800's

Rope Technology in the 19th century

Mizzi Langer -- first advertised rock climbing pitons (Mauerhaken)

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1a

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1b

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1c

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1d

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution-part 1e

Tita Piaz-Alpinisto Acrobatico (Piaz PartA)

Thanks, fascinating stuff and fantastic photos! One question, will George Ingle Finch be mentioned at all? Perhaps his achievements are not of the type to fit in this series?