Tita Piaz-Alpinista Acrobatico (Piaz PartA)

Mechanical Advantage #9a

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

CONTINUING FROM Pitons 1e. What has been fun about writing this history of technical tools is the familiarity of the path climbing history took from the first named Golden Age to the early steep rock climbing history of the Dolomites. I bumbled around the mountains my first few years of climbing (mid-70’s), learning basic ice skills and common sense the hard way, like going for summit bids on stormy days and nearly getting hit by lightning only metres away, glowing ice axes abandoned. Or as a 17-year old guide for Telluride Mountaineering School, finding myself 1000’ up on a steepening slab, too steep to downclimb, loose, and no belays. Myself, and two of the strongest student climbers of our seven-day traverse in the San Juans. “Clean” rack and nothing to protect—it was pretty clear we would all take the whipper if any one of us fell, and the sky was darkening. It was probably similar to how Carl Berger and Otto Ampferer felt on the Basso in 1899, we’d like to imagine. But I chickened out, and found an escape route to the side, above a steep couloir, and lucked out as the other guide of my team was just descending the walking route to the summit, and provided life-saving ice-axes to survive the step-cutting descent and then back to camp. It was pretty clear that a real rack, not just a mismash of big hexes and slings, to climb nice lines (which it was, a beautiful 1500’ buttress), and that I needed a lot more practice on using the tools effectively. So now it’s fun to write about my new favourite superhero Tita Piaz, after finally reading his memoirs, as he inspired many and brought new elegance to climbing the steep cliffs all around them, and showed how it could be done.

Tita Piaz

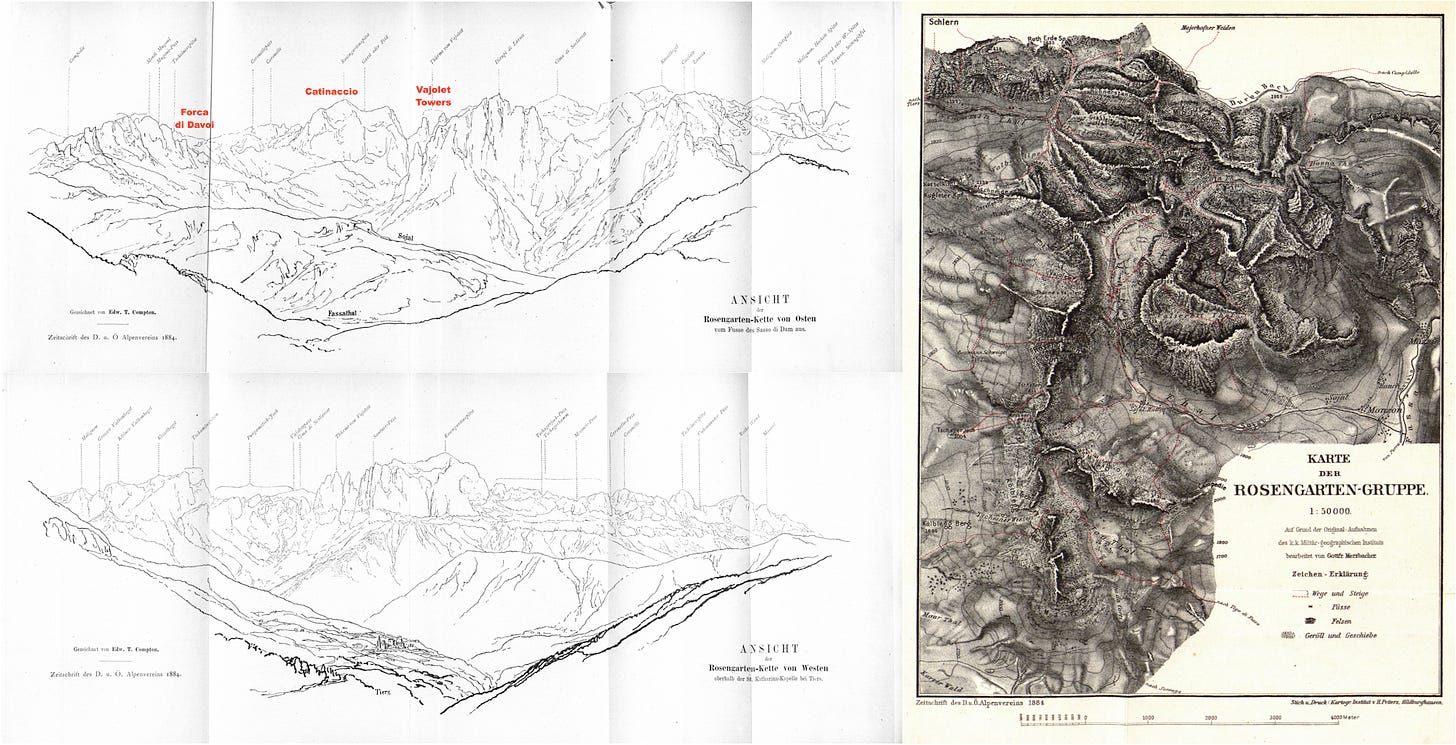

Tita Piaz grew up in Pera, the valley below the imposing Rosengarten summits and Vajolet Towers, in a house architecturally a mixture of cave and barn, with walls of tiny holds, cracks, dizzying traverses, and overhangs, “lending itself to the most varied exercises” (Casa Paterna). He writes he was “born a monkey right out of the womb” and was always on the lookout for new moves in his natural home gym. Also nearby was a 15m crag which he would solo, much to the concern of his family and the awe of his friends, a bold climber of anything and everything vertical, as well as an impressive gymnast on the bar.

Once as a youth, Piaz broadcasted his intent to climb the bell tower in Bolzano, 42 kilometres walking from his home in Pera, and everyone, knowing of his skill and daring, wanted to be there to witness the event. When the day finally came, he climbed the walls of the tower, shinnied up the long lighting rod, but just as he reached the famous wind-vane rooster on top, instead of celebrating and basking in the awe of the growing audience below, the police arrived (who knew him for other shenanigans), and he had to hightail a quick retreat, hiding in the belfry among “bats and spiders, mice and other similar creatures that probably also have strong reasons to escape from sunlight”. He remained huddled for hours until his friends found him and led him back into the light, but only after being assured that the “terrible priests of the urban law had left”.

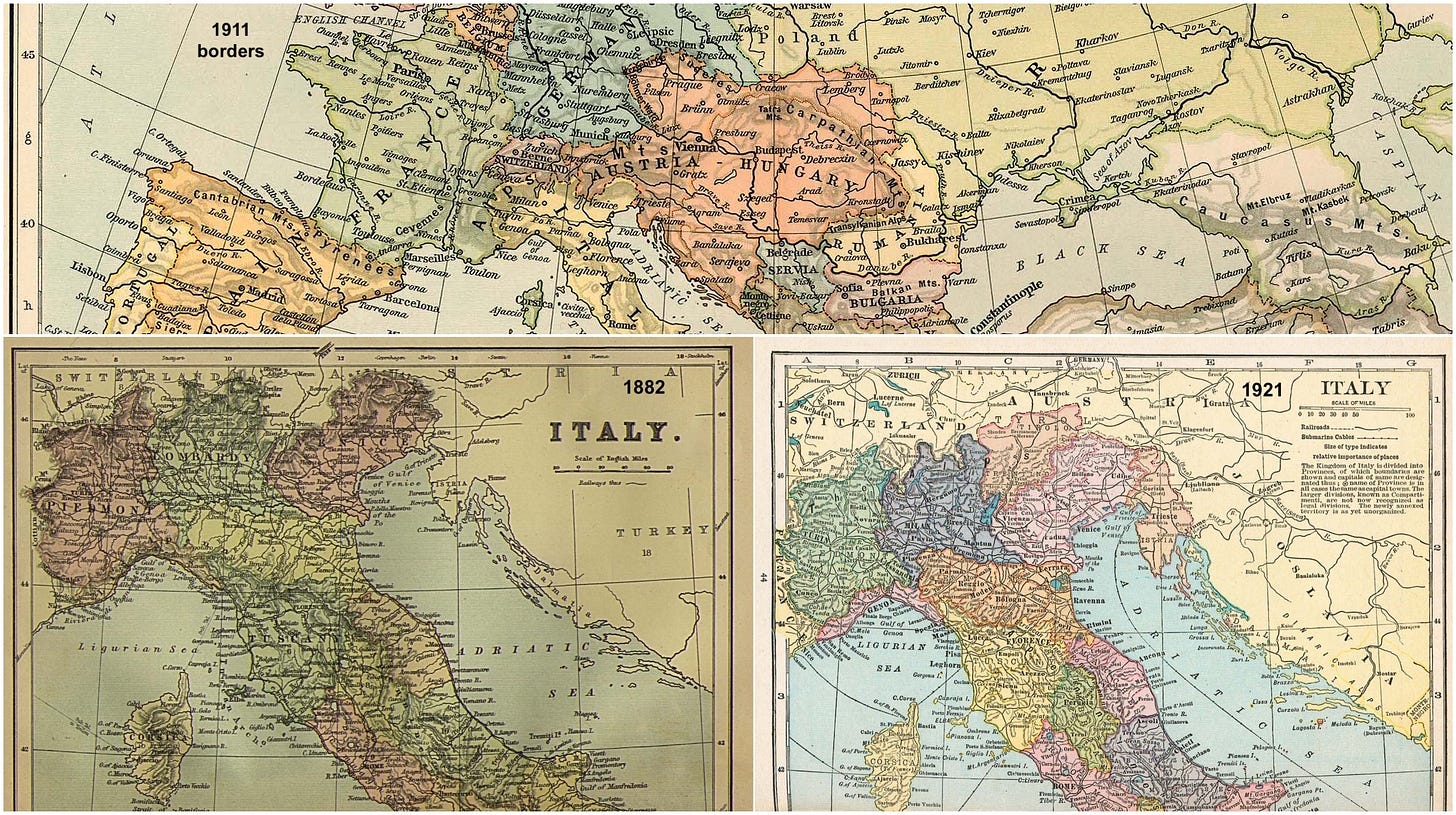

Piaz was what we today call a radical—he did not “suffer the stupid and cowards”—and was blunt about his dissatisfaction with any imposed rules over-indulged by society at large. He was a vocal irredento (Italian: “unredeemed”) who sought to reclaim independent nation-state status of the broader language group region then called—much to locals dislike—Welsh Tirol (now the autonomous Trentino province of Italy). He was antagonistic to the Austro-Hungary rule in which he was born, sometimes at expense of his personal freedom, and later opposed the rise of Italian fascism; in 1930 he was jailed as a subversive for his views. His contempt for the Nazis during their occupation in 1944 saw him treated brutally in prison for nine months, sentenced to death, but released as allied forces pushed north through Italy; soon after, he was elected mayor of his hometown. He lived a life on the edge, with many close calls.

Tita Piaz was a family man too. After a what was likely a wild youth in matters of love, he married twice, in 1903 Tita to Marietta Rizzi, the manager of the Vajolet hut’s daughter, and had three daughters: Olga, Pia, and Carmela. In 1913 he married again to Maria Bernard and fathered two more children: Nereo and Furio. He was an appreciated poet and writer in the Fassa Ladin language, and a renowned theatrical performer. He had a loyal dog named “Satan” who carried his ropes to the base of crags. He managed and built high mountain huts below the Vajolet Towers and other Touristenheim (tourist houses), sometimes at odds with building authorities, and was known as a loyal and generous friend to many in his community.

Tita’s tales in his book, “Half a Century of Mountaineering” are riveting, even with today’s over-exposure to all things “extreme”, and yet told with a wry retrospective awareness as he navigates the “crucible of the ideals of exuberant youth, the selection of values…”.

Piaz begins, setting the stage: “Imitating Rousseau, I confess my mistakes with candor, running the risk of losing the esteem of all past, present, and future mountaineers; maybe I run the risk of attracting the wrath of the gods on my miserable soul, having reached the point of weakness and with no regret, can enjoy the memory of being so naïve before I entered the realm of true mountaineering. Let him who is without sin cast the first stone!”

Before Tita knew anything about formal mountaineering, he set off to solo—because he knew no one with sufficient daring or who was “less unemployed than me”—a rocky summit on Forcella di Davoi where he had often passed with his father who worked both sides of the pass. Technical rock climbing had begun in the region, Winkler soloed the first of the mythical Vajolet Towers seven years prior, and various alpinists had passed through town after having first ascended summits known to the locals, but Tita did not have any knowledge of the techniques except to climb up! High up on his first real rock climb at age 14, ropeless and making technical moves with dizzying exposure, he suddenly felt remorse for not listening to his worried mother, and “lashed by the most genuine fear”, he retreated, and with the help of his good guardian angel, found himself back on reasonably inclined ground. “Defeated but, what matters most, safe and sound and out of the reach of so many horrors”.

But back on safe ground, soon he was torn between two opposing forces: “fear and wounded pride”, and after chastising himself a coward, back he went, studying the line a little better, and soon summited without “even remembering any difficulties worthy of note.” Tita Piaz’s climbing career had begun.

Emboldened by a climb with two friends of Col Ombert, the high peak on the other side of the valley, Piaz felt he was ready for the mighty Catinaccio, the imposing summit of the Rosengarten range. He had heard there was a spring on top, and imagining an Arabian Nights landscape, had to see for himself. He arrived at the hanging valley where the Vajolet Rifugio was later built, and got the first good view of the approach gully between “sinister, threatening towers”—one of which would later be christened Torre Piaz—and the “gloomy wall” he would later name Punta Emma. Legends had it that shepherds had made it to the summit, but once again, alone on a 200m steep headwall, he was confronted by fear and doubt, and after praying for his salvation, retreated and hiked back to town, feeling shamed by his perceived cowardice.

The following year, he managed to lure his two friends who climbed Col Ombert with him for another attempt at the Catinaccio. Armed with alpenstocks “as long as a year of famine” (the longer the alpenstock, the better the mountaineer, he mocks) and with two litres of grappa (a type of strong brandy, polished off before the rock climbing even began), they climbed in their socks, ropeless, to the summit. Of his memories on top, he writes, “This was one of the most beautiful moments of my life as a mountaineer, a luminous beacon of my memories that still sends auspicious rays to my soul”— if he had one day to re-live, it would be that moment of bliss. In a footnote, he retrospectively notes that the intoxicating combination of “the miraculous power of grappa” and beautiful summit temples would be a bane for some mountain guides, which he was soon to become.

Tita had been expected to gain a teaching degree in Bolzano, but the lure of the mountains was just too great, and he quit his master’s studies before completion. By this time, the Torre Winkler had been regularly climbed and guided, and he had heard that mountain guides collected 50 fiorini (then the same cost for a cow) for guided ascents. He couldn’t believe it was possible to earn such an astronomical amount in half a day. He became obsessed with climbing and guiding the famous towers.

Not yet 20 years old, he climbed Torre Winkler with a friend, “infinitely below me in skill” and 20m of old rope, “not even worth tying two sheaves of hay together”. The ascent was witnessed in awe by patrons of the recently completed Vajolet Rifugio below. Proud, for him it was the cumulation of an impossible dream, and the news of his ascent spread widely and gained the attention of other climbers, including the renowned guide Luigi Rizzi (who later partnered with Dibona for some of the biggest walls of the era).

With his rise to stardom, he sought a paying client for the adventure on the Torre Winkler, but his reputation as a wild daredevil preceded him, and no one would sign up for a paid guided trip with this “crazed captain” without permit (“bootleg guiding” as we say now—by this time guiding was a certified profession in Austro-Hungary). For practice, he took a number of “poor victims” to the summit of Torre Winkler, from all social classes—women preferred, he notes. It made no matter to him that they were “devoid of any abilities and filled with fear”; indeed, the less skill and more fear, the better as practice for a paying client. He made ends meet by portering loads from town to the Vajolet Rifugio and other areas (as a ‘carrier’), but he felt working as a lowly porter was beneath him, yearning to be set free on the cliffs of the high summits all around.

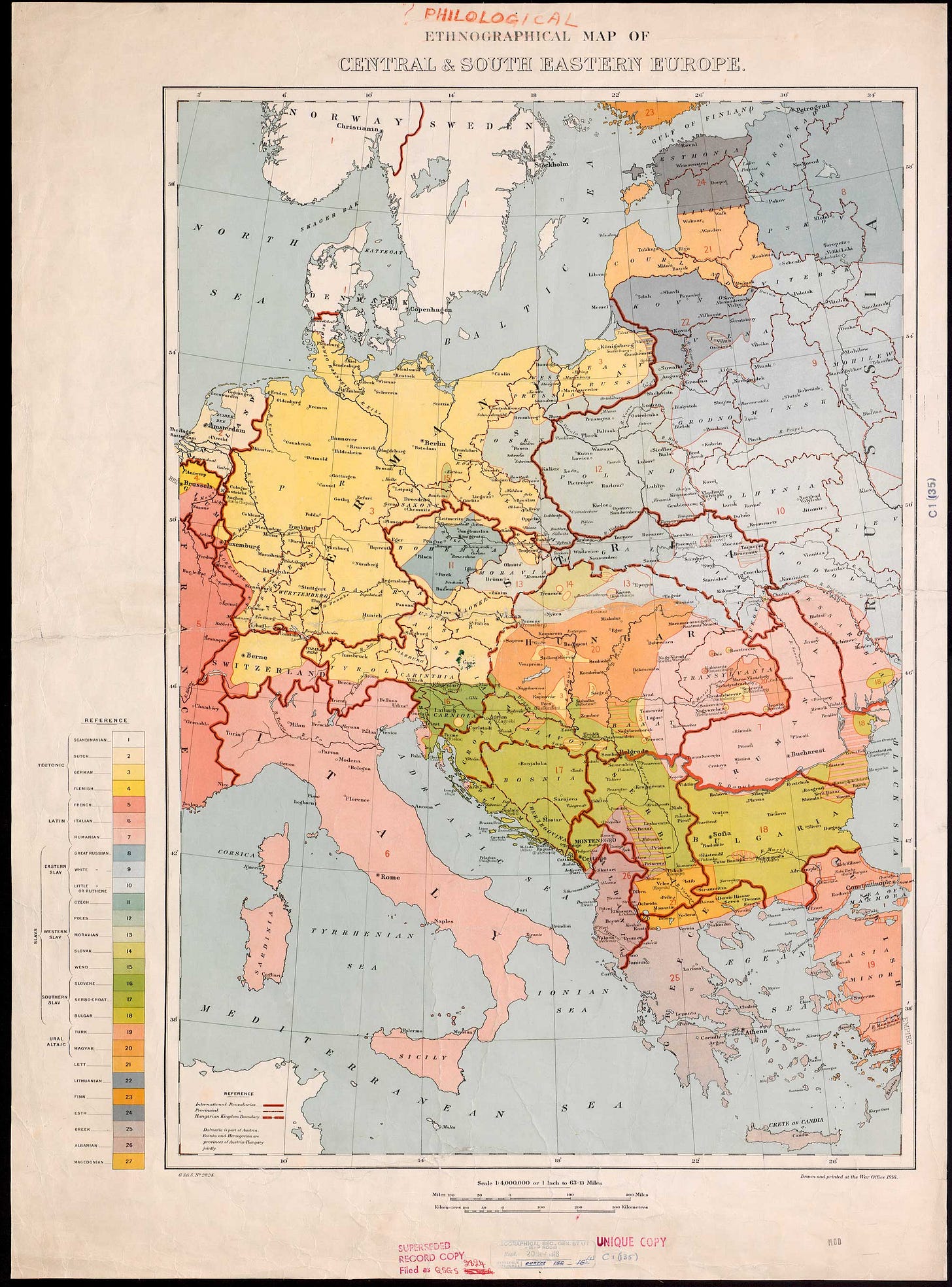

At this point in mountaineering history, the Rosengarten group had become well known. The German Austrian alpine journal published a 44 page monograph on the range in 1884, and another 40 page report in 1897, mostly defining nomenclature in both German and Italian—most of the landmarks in this area had different names in various languages (later, in the German journals, complaints of Piaz’s insistence on only using the native Ladin/Italian names was reported). The word on the Rosengarten was out, and many mountaineers came from all over Europe to climb there, and Piaz began finding clients for his guiding ambitions. The area’s famous legends were also a draw—King Laurin’s magic garden of roses— hiking in the range can be reminiscent of the time of dwarves and castles (one feels small amidst the wilderness of towers). In short, the Rosengarten was a destination with journeys to share. As the area became better mapped and identified in the German language journals, many northern mountaineers realised the potential for first ascents on majestic summits.

Eventually Tita contracted a client for the Catinaccio for seven fiorini, thanks to being at the right place at the right time—the client’s hired guide had failed to show up at Vajolet Rifugio on the day of the climb. Worried of the professionalism of his gear, Tita distracted his client with tales of the Winkler and Delago towers, painting the horrors of these climbs to prevent the client from noticing Tita’s worn and battered rope as Tita tied him in. About 50m up: “probably in the heat of showing off my extraordinary ability, I moved a huge boulder that with the roar of hell, fell toward the abyss, missing my poor pupil’s head by a few centimetres”. Pale and trembling, the client glared at Tita, but then said good-humoredly, “She starts well,” and they continued to the summit and back without further mishap.

At the rifugio, much to Tita’s astonishment after the close brush with death, the client asked if he could next be guided up Torre Winkler the next year. Yes! he was becoming a guide. On the triumphant hike back to town—tattered trousers, rope over the shoulder, rock shoes tied outside his pack—classic guide posture—he couldn’t believe his luck, especially when the client tipped 3 extra fiorini. His wages were spent in their entirety that night, celebrating and playing skittles at the Café Larcher.

In 1894 Hermann Delago had climbed the westernmost Vajolet Tower, (Torre Delago), calling it harder than Winkler’s route. By 1898, Torre Delago was considered the most difficult climb in all the alps, the absolute limit of possible. Only a few of the best guides and climbers—Dimai, Bettega, Zugonell, Rizzi, Innerkoffer—dared repeat it, and guideless ascents were big news.

Tita joined up with an old school friend, Antonio Schrott, for an ascent of the feared Delago route, perhaps the 10th ascent. Schrott was also a bold amateur climber of note, having climbed the Winkler route and other testpieces. The only thing they knew of the route was that there was a difficult smooth chimney that required good technique—of which they knew none! Piaz writes about squirming up the chimney like a snake, at his limit, only having made it thanks to his gymnast abilities and grit, “arriving at the summit with the last breath that remained in my body, I screamed to the universe, ‘The world belongs to the brave!’”

Tita muses how at the time he was in search of an unclimbed tower he could give his name to: “Piazturm!”— then clients would be coming from all corners of the world for the “honor of attaching themselves to my rope,” and he would be suffocated by the multitude of customers, rushing like dogs to the door of a lover. It would be raining fiorini!

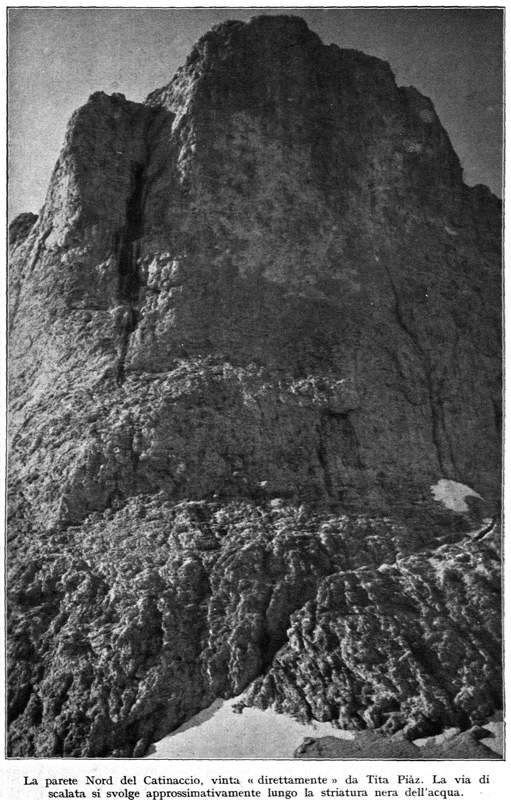

Later, in response to doubt from a guide who didn’t believe could have climbed the Delago with the technique and way he described, Tita boasted that he could and would climb the prominent and fearsome unclimbed chimney on the north pillar of Catinaccio (now Punta Emma). Tita made a bold entry at the Rifugio, advertising: “First climb of the North Pillar of Rosengarten; difficulties not much higher than the Stabeler. Tariff: 25 Fiorini” even though he hadn’t yet climbed the route!

Note: the middle Vajolet, Torre Stabeler, had been climbed in 1892 and was considered considerably easier than Torre Winkler.

Now that Tita had laid claim for his climb in words and writing, it was time to “launch” the route. Again, in pages of writing, he describes his bravado and how his first ascent of Catinaccio’s north pillar would launch him into greatness (he precedes many of his climbing stories—tongue in cheek—with this kind of swaggering prologue). He first found a way to the summit from the northeast (as descent route), then, while attempting the first ascent of the 300m buttress, he methodically climbed to a particular crux—an overhanging roof—then down-climbed for a break and further review. Theodor Christomannos, the secretary of the German Austrian Alpine Club, witnessed one of the forays. Back at the Rifugio, Christomannos put 17 fiorinis in Tita’s hand, and said, “Dear Piaz, buy yourself some decent climbing shoes and you’ll be able to do it”. The moral support and the better shoes helped, and Tita’s subsequent solo first ascent of Punta Emma set a new standard. But it was not to be named “Piazturm”—Piaz Tower—as honor demanded “his” tower be named by a partner, not himself. This one he named after the Vajolet hutkeeper’s assistant, Emma Della Giacoma, after he took her up the easier route to the summit. The north buttress chimney on Punta Emma was one of the longer hard rock climbing routes (5.8) in the Alps for some years ahead.

footnote: The gravestone for Christomannos (1854-1911) bears the inscription, according to Piaz: “The man who wanted everything for others, nothing for himself.” Christomannos, the son of a wealthy Greek family of merchants living in Vienna, was instrumental in creating the “Great Dolomites Road” connecting mountain ranges from Bolzano to Marmolada, and was known to be a generous donor public good in Merano (Bolzano area). Piaz remained grateful to Christomannos for his gift of real climbing shoes, even when he later became a political enemy and said that Christomannos “tried to hurt me”.

Tita Piaz—Part B to come—Tita sets new standards in speed climbing and enchainments, guides many first ascents, and begins traveling for significant ascents in the Dolomites and North Tirol. From 1902-1912, Tita was part of a growing cadre of technical big wall climbers who set new standards in the Eastern Alps. His protection systems were advanced for the time, he became one of the most efficient first ascensionists of the era. We'll look at some of his 50 first ascents (and descents) to see what we can figure out of his mastery of pitoncraft, as well as other technology, such as footwear, which was another primary driver of advancing rock climbing standards of this era.

Postscript: part of the reason I have gone into such depth of Tita Piaz’s early climbing career, is that it’s probably similar to many climber’s introduction to rock climbing even well into the 70’s, the age of stiff goldline ropes. As a beginner, hearing and vaguely knowing of great climbs and climbers, with little or no access to good information or guidance, and eventually going out and figuring it out for oneself, often with a few close calls. Then, choosing to live the full time climbing lifestyle, scrapping for any work and spending cash quickly, the only thing that matters is the next climb (an 80’s version in the Valley included scarfing and searching for aluminium deposit cans, being ready for rigging and film work, bootleg guiding El Capitan—twice for me—living from rescue check to rescue check, and very gradually getting better set up. In my case, getting a van—with no motor—as a winter survival shelter between climbing seasons, probably at least as good as an seasonal bivy spot in the Rifugio ;). It is also interesting to map Tita Piaz’s attitudes on risk, as it evolved with his climbing style and ambitions.

Eastern Alps Geography and Early Alpinism

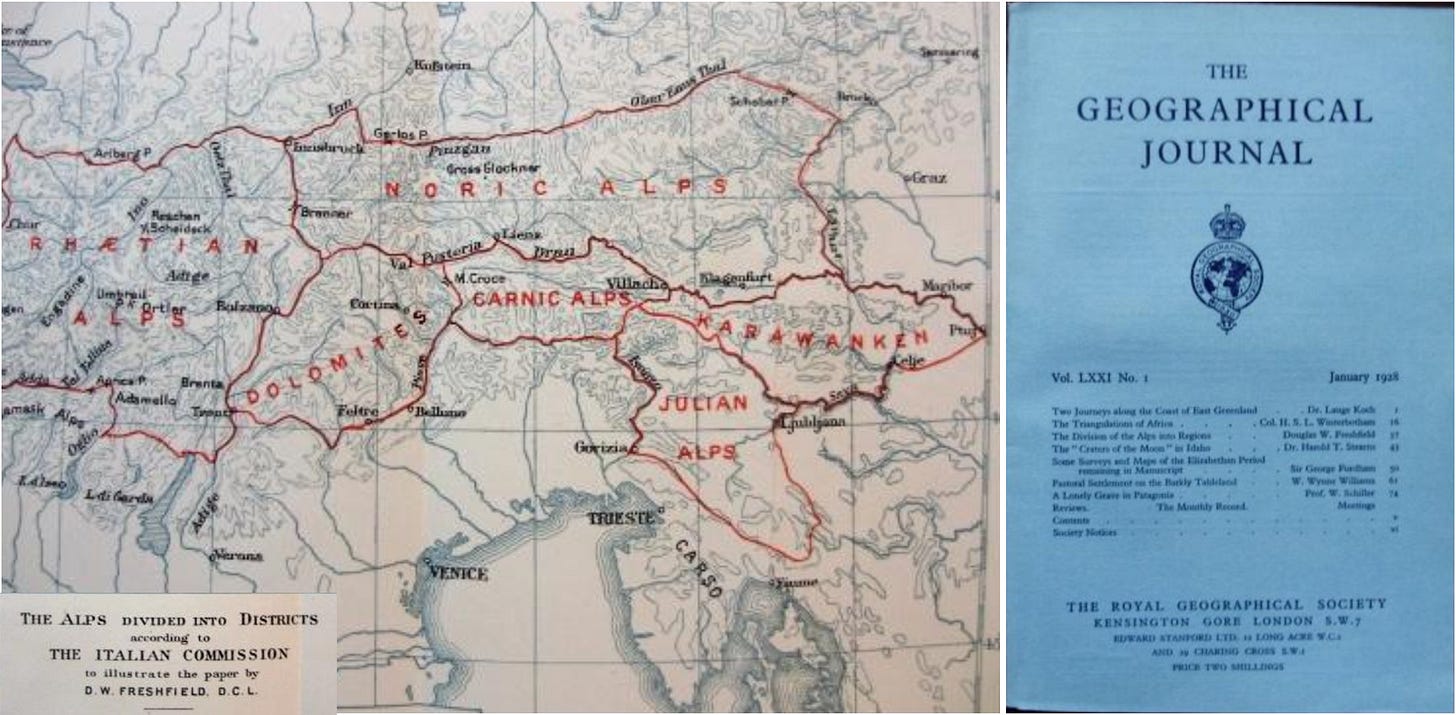

Most of the big rock climbing breakthroughs in the early 1900’s were in Austro-Hungary, a region with 14 major language groups. In north Tirol, there are the Wetterstein, Karwendel, and Wild Kaiser ranges—the German-speaking “Münich climbers”, Hans Dülfer and others, pioneered new big wall techniques in these ranges (next article). In the south, “Trentino, Cisalpine Tyrol with its geographical and natural frontier (the Brenner frontier)” (Treaty of London, 1915), the great Dolomite big walls: Marmolada, Civetta, Furchetta, Pelmo, Drei Zinnen, tall spires in Brenta and Rosengarten, all the valleys and ranges in the South Tyrol and Trentino region—areas all ceded to Italy in 1918. Tita Piaz was from the Catinaccio/Rosengarten area in the south near the Vajolet Towers (Western Dolomites).

ALL LINKS

In the Beginning: Subtle Means and Engines

The Modern Era of Mountaineering (1786)

American Trail Builders, 1800's

Rope Technology in the 19th century

Mizzi Langer -- first advertised rock climbing pitons (Mauerhaken)

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1a

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1b

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1c

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution--part 1d

Climbing Pitons Early Evolution-part 1e

Tita Piaz-Alpinisto Acrobatico (Piaz PartA)

The Telluride story is from 1978 or 1979. I went there 4 times, first two years as a student(1974 and 1975), then as a “guide schooler”, then as a full fledged guide, responsible for groups of 8 or so for 7-9 day adventures in the mountains of the western slope. Writing about the history of the area is bringing back memories of those wild times. They don’t make mountaineering schools like they used to. At least, not of the caliber of Dave Farny.