Trains and Kain (Canada climbing to 1916, part 1)

Mechanical Advantage Big Wall series by John Middendorf

Buy the books here:

Volume 1: (mostly) European Tools and Techniques to the 1930s

Volume 2: (mostly) North American Climbing Tools and Techniques to the 1950s

Trains

The rising ‘Age of Steel’ in the 1800s spawned so many new innovations in sport, transport, manufacturing, and war. Emerging triumphant from the Iron Age with new steel mass-production methods by the late 1800s, the Steel Age was initially driven by the railroads, which in turn led to greater access to the mountains. And of course, as is clear by this series, more metals eventually found their way into the North American mountains as tools for climbing, leading to celebrated accomplishments.

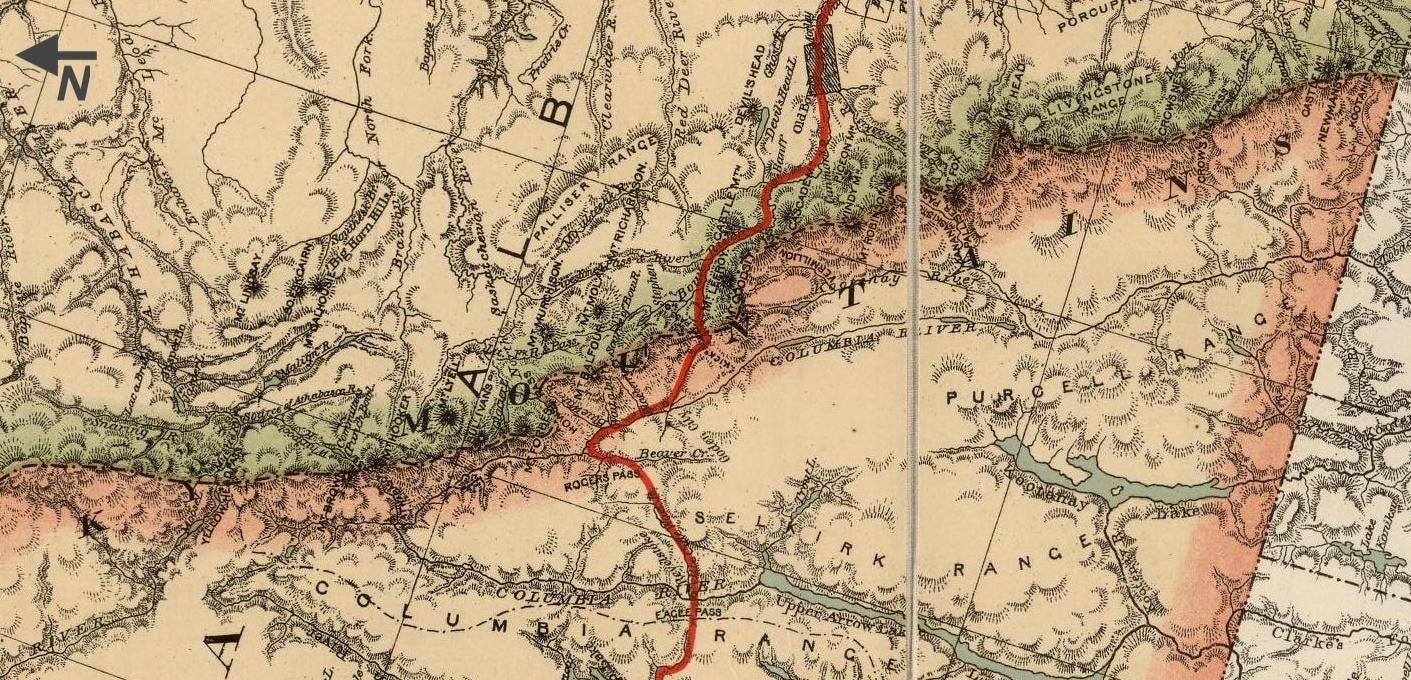

The Pacific Railroad in 1869 spanned North America and was a monumental effort by the train industry, spurring American steel manufacturing to new levels. In November, 1885, the Canadians completed another transcontinental railway, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), and soon began promoting leisure train journeys.

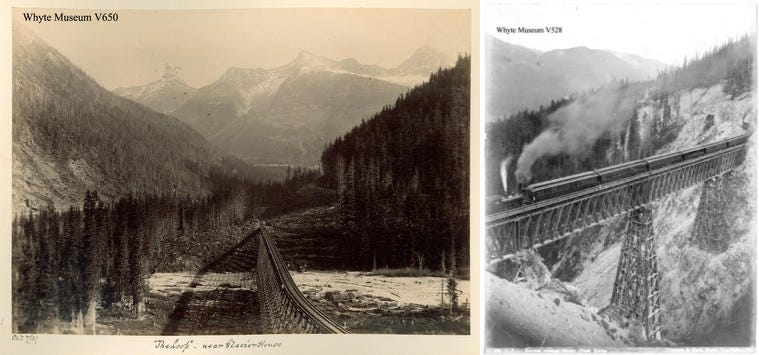

Rogers Pass …

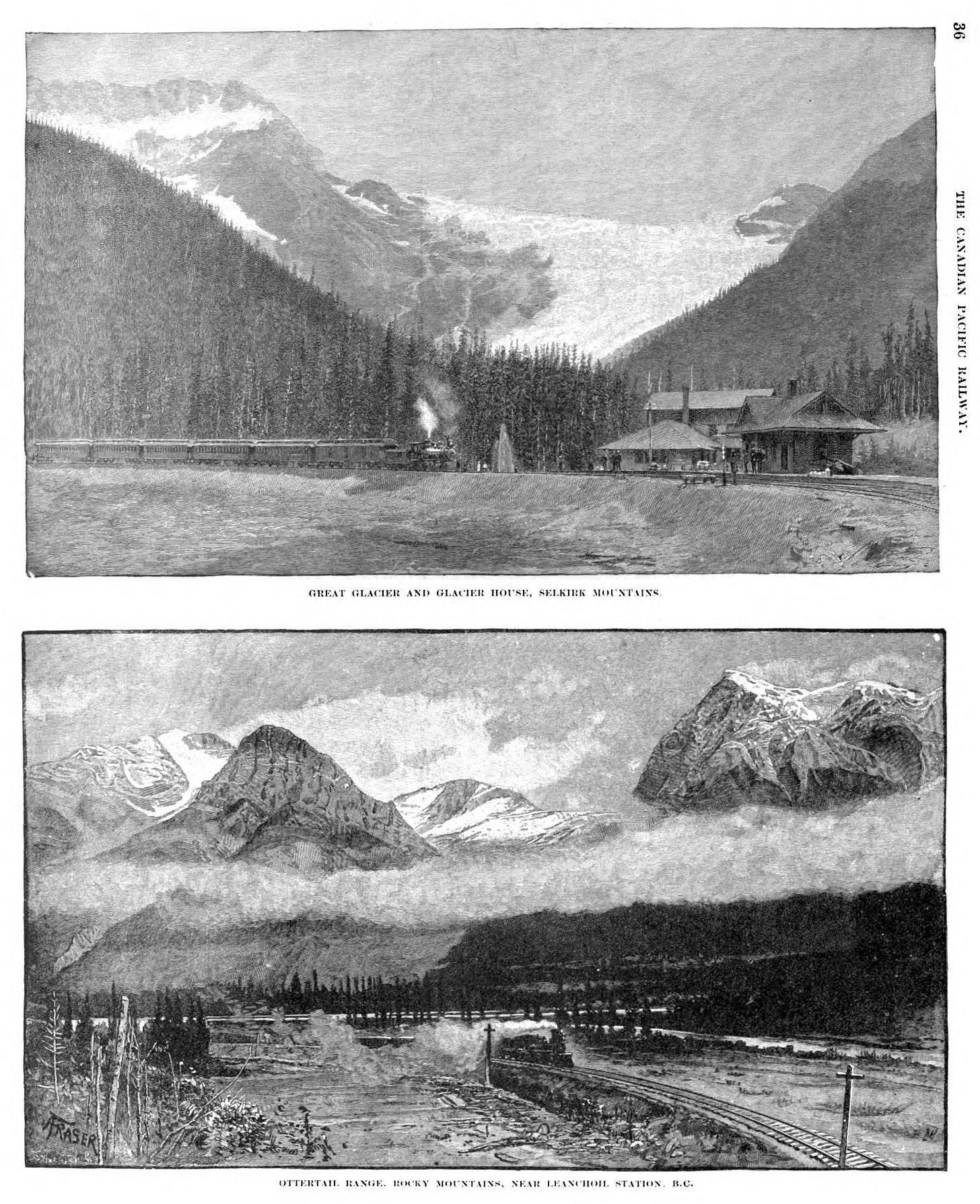

The concentrated human effort to create the first transcontinental railways, completed by tens of thousands of workers from start to finish in a few years, is difficult to imagine today. One of the most problematic passages in establishing the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway was the route through the Selkirk range. The line over Rogers Pass, just west of the Continental Divide in British Columbia, was one of the great engineering feats of the era. The long grades up steep mountainsides were fraught with avalanches in winter, a problem only partially solved by building snowsheds over the track in the primary avalanche gulleys. Workers struggled to keep the snowsheds in repair and to keep the track clear from snow in dangerous conditions—hundreds of workers were killed in avalanches. In one 1910 event, sixty-two workers clearing the track were suddenly buried and then frozen and suffocated under meters of snow.

Specialist workers, adept with ropes and vertical positioning, were also employed. This type of skilled labor would have been instrumental for many of the new wonders of engineering in the late 1800s using steel, concrete, and rock anchoring techniques for civil projects of unimaginable new scales. In the Rogers Pass area, the work of creating and maintaining anchored foundations, cedar and stone-arch drainage culverts, and supporting pillars would have been difficult and dangerous skilled high-angle work in the steep mountain environment. Yet those heroes are largely forgotten, and the challenge of working with engineers to create structure and form are often taken for granted despite the frequency of accidents (footnote). Some evidence suggests that stonecutters and high angle specialists were largely from Italy, and were later known to have helped build the elegant stone architecture of the region with Scottish stonemasons. Others were literally reshaping the terrain using high-pressure hydraulic systems to move vast volumes of earth. To maintain the railroad and its services, life would have been a constant multi-cultural bustle of a myriad of independently run large projects. The increasing tourism and expanding mining operations only added to the hubbub, and the internationality flavor of the “safe” spots, like Glacier House, an oasis surrounded by a hostile mountain landscape, was a favorite place for guests and employees alike.

Footnote: For example, two workers died in building the Stoney Creek bridge, pictured above, which at the time was reported to be the highest timber bridge ever built. It was one of the first bridges to be replaced with a wrought iron bridge in 1894, then later with a steel bridge. The wooden brides were not only rickety but also prone to burning up in the frequent large-scale forest fires being set off both by natural causes and human disruptions in places once quite pristine.

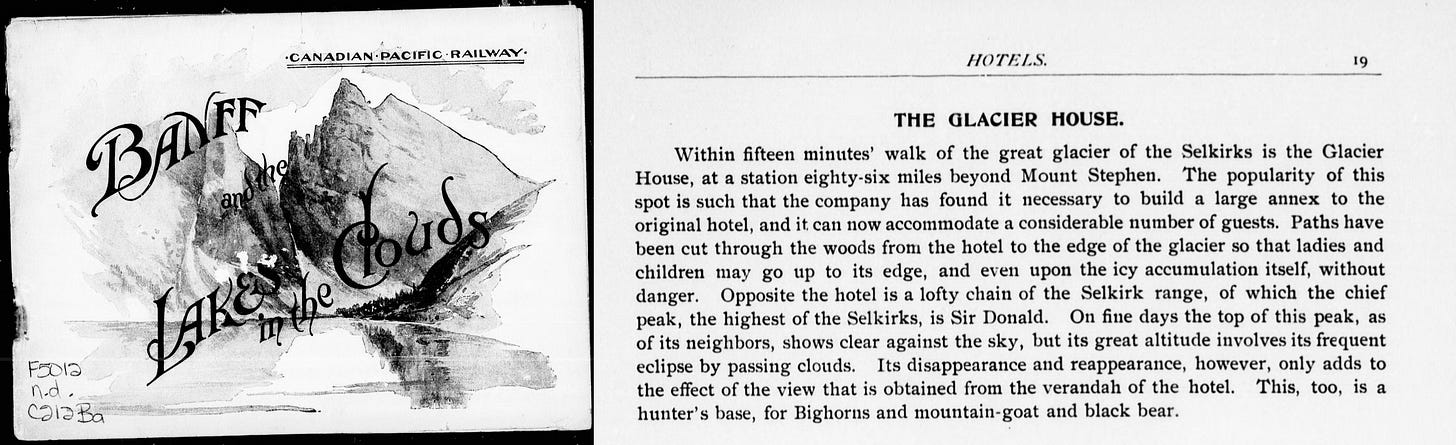

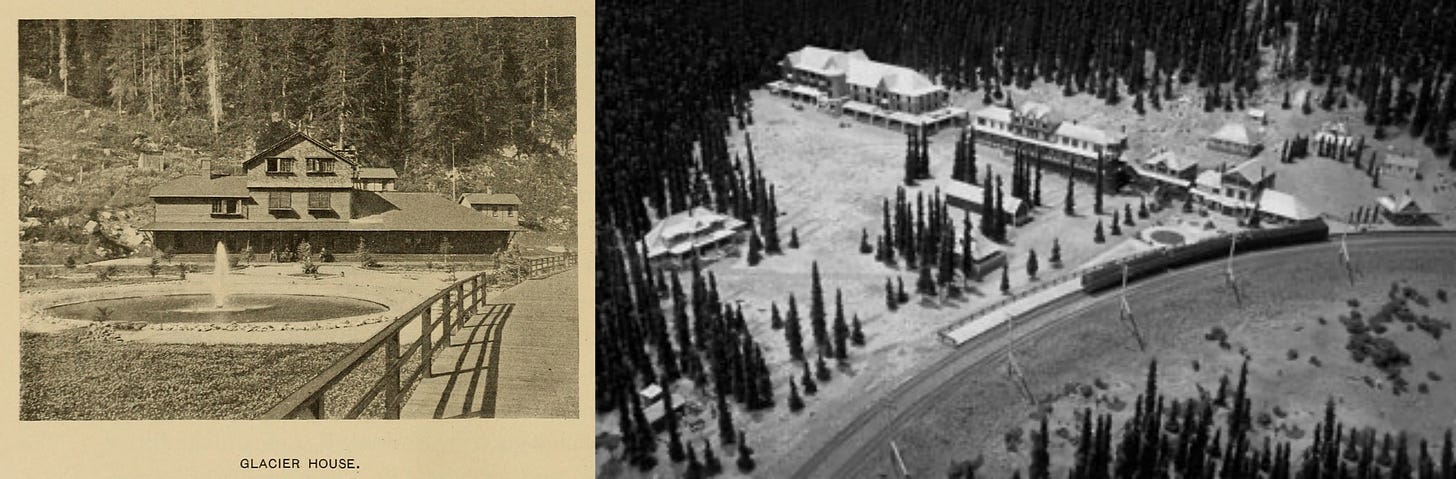

The Glacier House (1886-1929)

To save the weight of pulling dining cars over the steep and twisting mountain tracks through the Rockies and further westward, the railroad initially installed static dining cars on scenic sidings along the line. These eventually morphed into dining lodges, then comfortable hotels. The Glacier House, three miles from Rogers Pass, was one of the first. An early manager of the Glacier House described it as a “resting-place situated in the heart of the Selkirks. The hotel is built beside the railway, in a beautiful amphitheatre surrounded by lofty mountains, of which Sir Donald, rising 8,000 feet above the railway, is the most prominent. Northward stand the summit peaks of the Selkirks in grand array, all clad in snow and ice, and westward is the deep valley of the glacier-fed Illicilliwaet River, leading away to its junction with the Columbia. The dense forests all about are filled with the music of restless brooks, which will irresistibly attract the trout fisherman, and the hunter for large game can have his choice of ‘big horns’, mountain goats, grizzly and mountain bears. No tourist should fail to stop here for a day at least, and he need not be surprised to find himself loth to leave its attractions at the end of a week or month.”

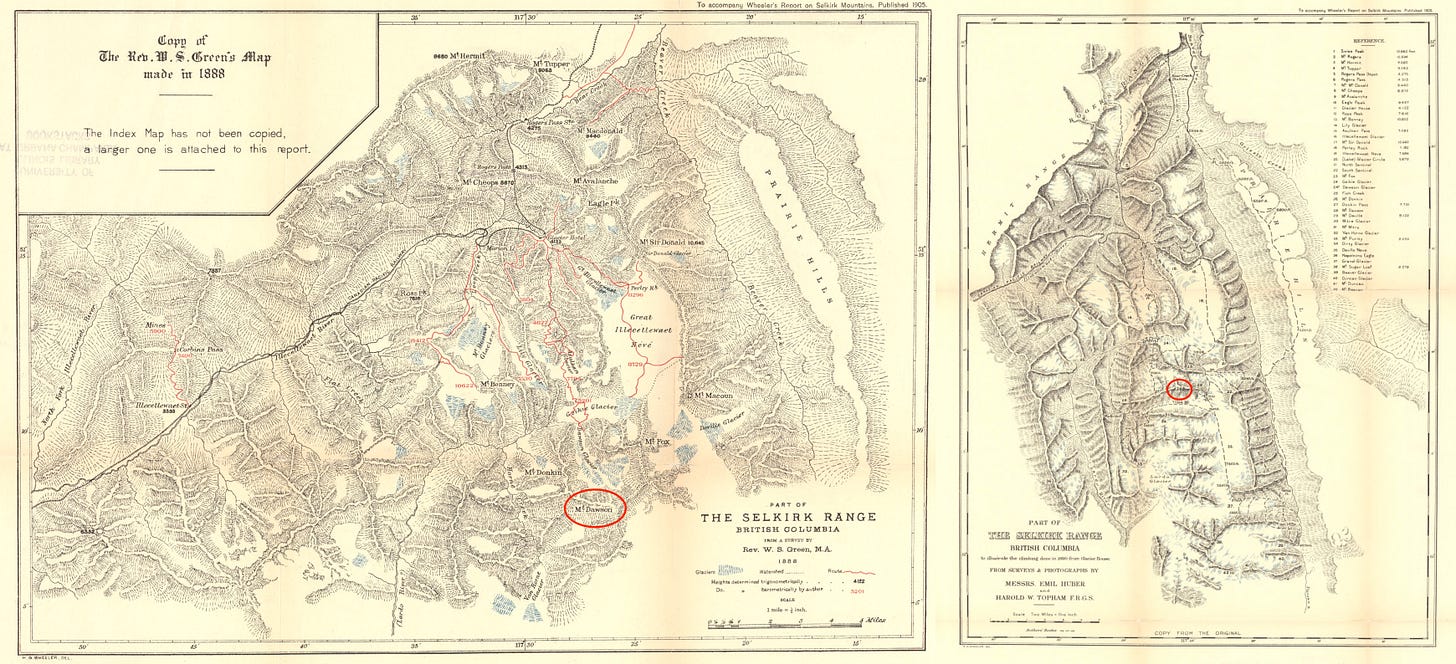

The ease of access deep inside a mountain range and the comfortable base camp brought climbers from all over the world, and as more trains and trails were built. The early era (to about 1900) climbed the major peaks made more accessible by Green’s survey in 1888—as far south from the Glacier House as Mt. Dawson.

Trip reports often began at Glacier House as starting point, e.g. Charles Thompson’s report in the 1896 Appalachia of a trip with Fay and Abbott, “On Saturday morning, August 10, we left Glacier House by the Marion Lake path for the summit of Mt. Abbott. Our start was late (9.25), our plan indefinite.” The report is followed by a description of the naming of the twin peaks of Castor and Pollux (the former noted as a rock climb) and an exciting high alpine traverse on the Asulkan Ridge. Despite major features already having local Indigenous names, most features were renamed by the surveyors and climbers at this time, though a few names survived, such as the Asulkan (“wild goat”) Valley and the Illecillewaet (“swift water”) River.

Starting in 1897 (footnote1), the railroad began contracting seasonal mountain guides from Europe to run excursions from its hotels. The guides were provided their own building and were hired out for $5 per day from the Glacier House, leading tours for both hikers and climbers to glaciers and summits. At its peak, the Glacier House had close to one hundred guestrooms and a half-dozen outbuildings for guides and other employees. By 1903, running water and a sewer system, electricity, steam heat, an observation tower, billiard rooms, and a bowling alley were fully installed. In 1904, A.O. Wheeler, a frequent resident of the Glacier House, described it as "most luxurious and homelike— fitted with every modern accessory to comfort." (footnote2). Huts were also being built further afield in the surrounding mountain ranges. Quicker access to the mountains was increasing.

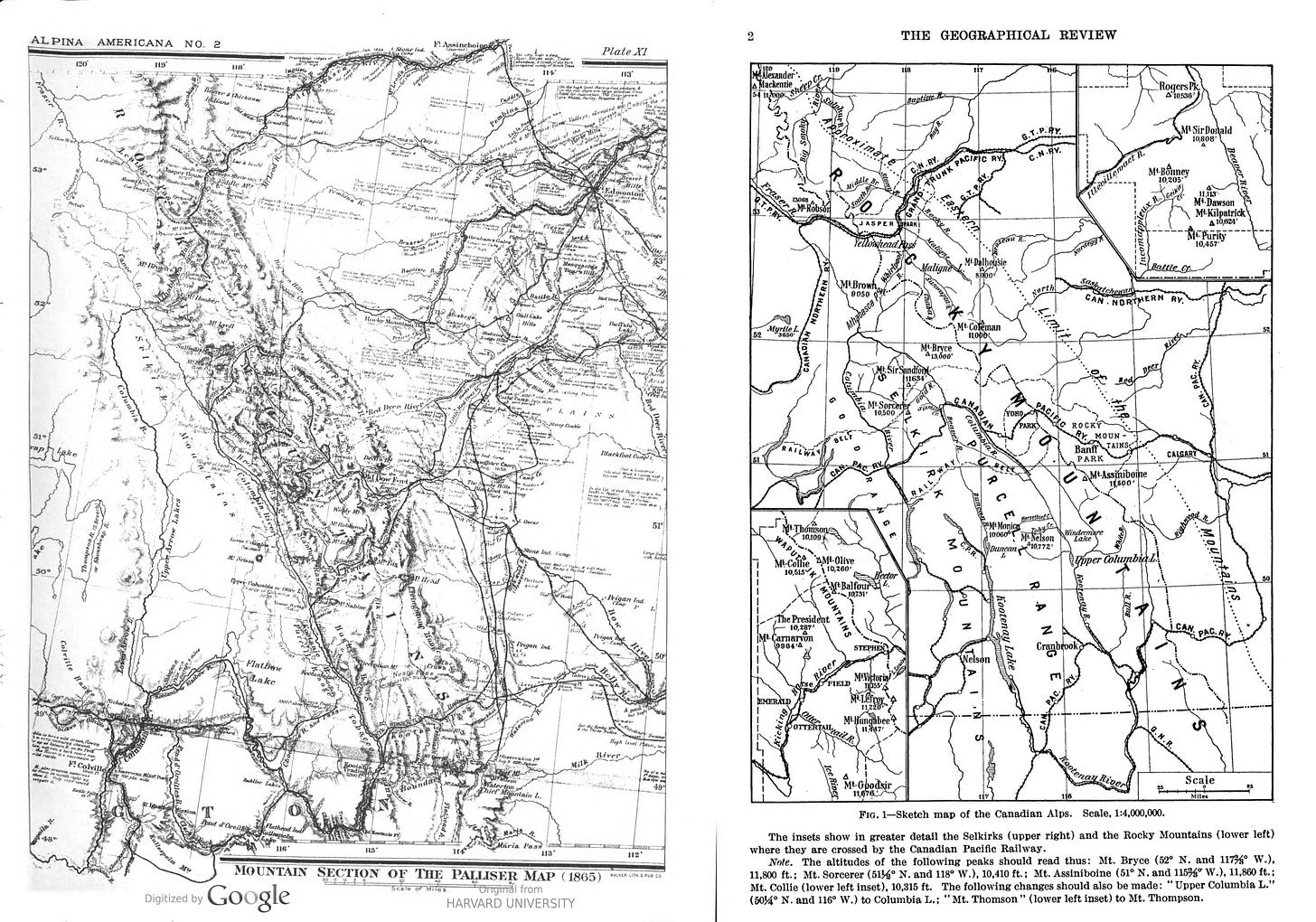

If there was ever a “golden age” of climbing histories (and there are many), the wave of climbing made possible in Canada by new trains and trails, with the centerpiece Glacier House, where all great mountaineers would spend some time, would be one of them. The Wheeler survey (1901/2) extended access to the range further south, and as Charles Fay notes in the 1916 Geographical Review, by 1908 “a new epoch for this region began”.

Footnote1: Finch (ref.below), records that Peter Sarbach from Switzerland, who had been a carrier for one of Whymper’s Matterhorn attempts, was the “first professional guide” for the CPR and arrived in 1897 for a single season. In 1899 Edward Feuz and Christian Hasler were hired as guides for the Glacier House.

Footnote2: For his surveys, Wheeler often base-camped his team at nearby Roger’s Pass, which started as a bustling trading post, but was then abandoned by 1887 due to avalanches and then only used in summer. In the 1915 Glacier House season, at its peak, nearly 13,000 people registered, in addition to countless day visits from travelers on the train. In 1916 the Connaught Tunnel was carved, bypassing Rogers Pass and the Glacier House, and from 1916-1925 the Glacier House only averaged 3000 overnight guests per year. The hotel officially closed in 1925, but guides were still permitted to use it as a basecamp for a while. The hotel was demolished in 1929. (Finch, 1987).

Arthur O. Wheeler and “Indian Trails”

“Unless you know devil's club and the jungle mixed with its forests you know nothing of trailless travel in the Selkirks” (A.O. Wheeler)

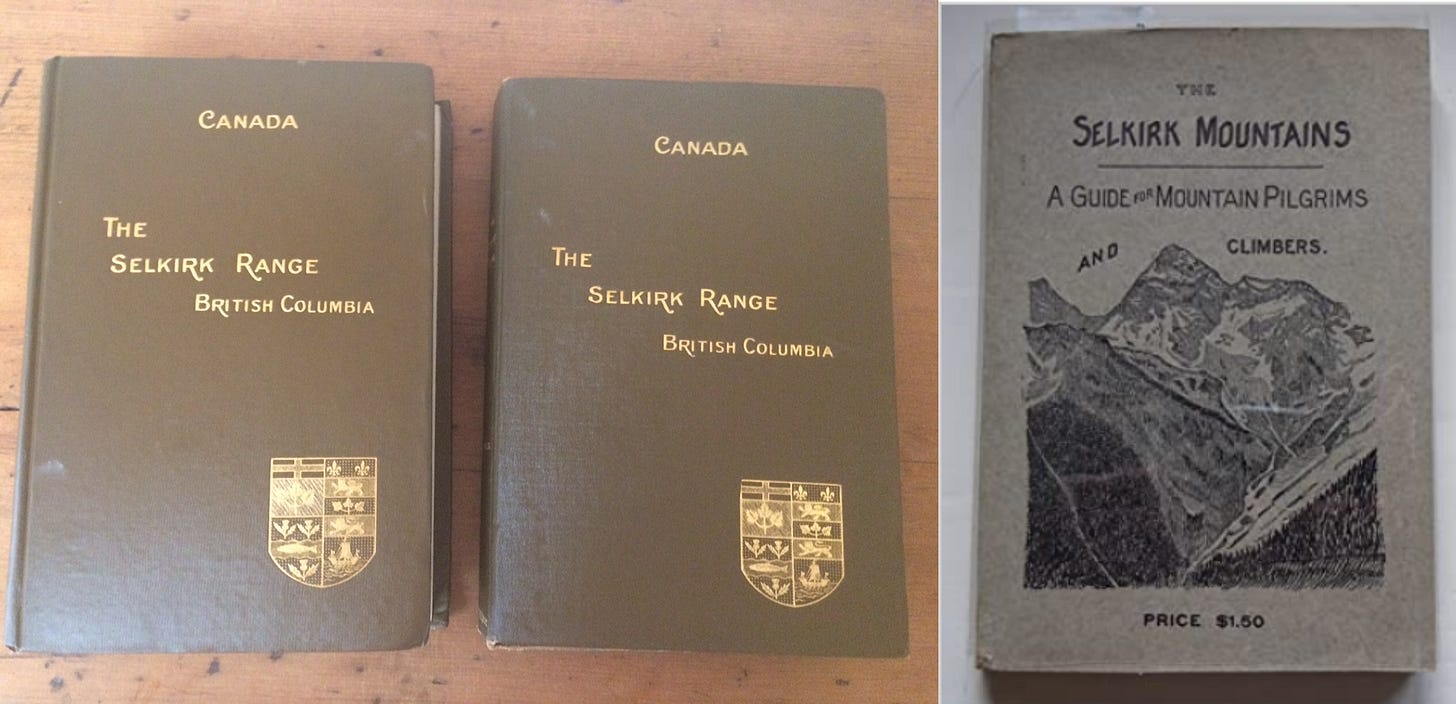

A.O. Wheeler, a talented surveyor/mapmaker and mountaineer, published a comprehensive survey and guide to the known history of the Selkirks in 1905, using a relatively new topographic map method using stereographic photography, an efficient process that captured the required data in the short summer surveying season which could then be processed over the winter months. In addition to detailed topographic maps, Wheeler documented everything else known about the region and was one of the first mountaineering guidebooks in North America (footnote).

Footnote: Wheeler’s book, The Selkirk Range (1905) also documents all known climbs and summits, even a chapter to “Lady Mountaineers in the Selkirks”. Interestingly, Wheeler reports that Edward Whymper, who would have been in his 60s at the time, was at the same time also hired in the Rockies to “conduct explorations and surveys in the interests of the Canadian Pacific railway company”. It sounds more like a climbing trip, though. Fay reports Whymper made “many interesting trips, including several first ascents”, with his four traveling guides, Joseph Bossoney, Christian Kaufmann, Christian Klucker, and Joseph Pollinger—though only two (Mt. Habel “Hidden” and Mt. Collie) are listed in Fay’s 1911 Alpina Americana monograph.

Today, well-traveled trails lead everywhere in the Selkirk and Purcell ranges, but back then, the biggest impediment to accessing the mountains was to first establish a path through the thick and tall vegetation which blocked all view. Wheeler reports, “The devil's club (prickly aralia) may be numbered by millions and they perpetually wounding us with their spikes, against which we strike continues falling incessantly.”

As pretty much everywhere in North America, the early surveys followed Indigenous paths, often employing guides from the local tribes, and the first mountains to be climbed were those with the least vegetated paths leading above treeline, or those that already had a hunting or fishing trail leading close to the mountain. The true challenge of these peaks was the difficulty of getting there (footnote1). For example, during several weeks of the toughest mountain work, Green’s survey expedition only documents a point less than seven miles from the railroad. In one particular section, it took “seven hours of hard work (for) only one mile and a half through the tangle” (about 300m per hour). Mountaineers needed help. Wheeler writes, “To those journeying through the mountain wilds, the difference of an Indian trail and no Indian trail becomes very apparent.” (footnote2).

Footnote 1. On his first expedition in 1881, Major Rogers hired ten “strapping young Indians” from “Chief Louie” (footnote3) with an “ironclad contract” of $1 per day (four shillings) for trailblazing and portering 100-pound loads for 20-minute runs with 5-minute rest in-between, with forfeited wages and 100 lashes as penalties. Grohman, a member of the Reverend W.S. Green’s survey in 1888, notes that the people from the local tribes were “no good on ice and won’t go on it” (but who would with 60-100 pound packs and no nailed boots?) but their skills for finding and blazing trails in their traditional hunting grounds was legendary. Grohman writes further of the men picked as porters and guides from a tribe of the ‘Lower Kootenay Indians’: "White porters require so much for their own comfort in the shape of blankets and food and are generally so unused to it, that they can pack but little besides their own outfit, while one of these extraordinarily hardy and frugal Kootenays, with nothing but a breech-clout and an old goatskin of his own to carry, will, with a 60-pound pack on his back, walk and climb away from an average mountaineer, while, unburdened with aught but his own outfit of ounce weight and his "fire-squirt" (rifle), I will back a Kootenay to beat by miles, in a long day's climb, the best white mountaineer Switzerland or Tyrol ever turned out; and I am speaking with a twenty or more years experience in the Alps.” See also Fay’s description in 1916 Geographic Review.

Footnote2. Full quote: “Nor must it be overlooked that most of the early traveling in these regions was by paths and trails previously mapped out and traveled by the Indian inhabitants, their lines of communication when passing to and fro on hunting expeditions. The Indian applies his natural ability in this respect in a wonderful manner and, as a rule, his selection of routes is seldom at fault. They furnish fair samples of engineering skill, while his knowledge of topographical formation, in which he is silently trained from his earliest youth, enables him to see at a glance the proper place to look for a road. With, possible, the exception of the Kicking Horse pass, it is likely that the passes entered and recorded by Sir George Simpson and Capt. Palliser's parties were traveled Indian routes. To those journeying through the mountain wilds, the difference of an Indian trail and no Indian trail becomes very apparent.” (A.O. Wheeler, The Selkirk Range (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1905). Another tale of Devil’s Club: “Travelling is very difficult, owing to the thick growth of willows, scrub maple, juniper and devil's club. Devil's club! What an experience is devil's club! Imagine a bare stick an inch thick and five to eight feet high with a spread of tropical-looking palmated leaves at the top, set off by a bunch of bright red berries. The entire surface of the stick is covered by sharp, fine spines and the canes grow so close together that sometimes it is impossible to force a way through them without using an axe. The points of the spines break off in the flesh…” (Wheeler, 1905 and 1912).

Footnote3: Various heads are recognized with English names in the treaties at the time. An 1895 treaty with the Nakoda (“Stoney Indians”) list the main chiefs in the region as Chief Abel and Headman Pielle (Kootenay), Chief Pierre Kinbasket and Second Chief Charlie Kinbasket (Shuswap), and Chief John Cheneka and George Crawler (Stoney) in an agreement structured by the Northwest Territories Commissioner of Indian Affairs regarding each tribes hunting ground boundaries.

With help from Indigenous local guides, Wheeler and his team extended access much further with more and was able to map and provide access to a huge number of summits. Konrad Kain, after a hard season of guiding at Lake O'Hara on the Alpine Club of Canada’s 1909 summer camp, writes of the summit view from Mt. Sir Donald (which he climbed on one of his few days off), “Unnumbered peaks and glaciers lie spread before the eye. With a good glass one could easily count more than a thousand peaks.” Not just access, but Wheeler provided one of the most enticing climbing guidebooks ever published, with detailed information and beautiful illustrations.

With increased access through the bush, and the information shared by Wheeler, the Selkirks became a hot spot—first ascents with the opportunity to (re)name your conquest (footnote) were there for the traveling, and climbers from Europe and the East Coast flocked to the region, often with their own “Swiss Guides”.

At this stage, nearly all “modern” North American climbing was the double-guide method perfected in the Western Alps. Clients often went with small parties, with dedicated guides in the back and in the front as a continuously roped party. Their role was to keep clients safe and also to cut steps up steep icy slopes, sometimes ahead of time in preparation for the client’s ascent. As in Europe in the mid-1800s, the concept of “guideless mountaineering” was discussed and sometimes practiced, but most respectable ascents involved the safety of guides. Gear was hard to come by; Wheeler notes in 1905 that “alpenstocks, ice-axes, rucksacks, rope, and all other adjuncts of the mountaineers personal outfit much be brought from Europe or in the large centres of the United States, for at the present time there is no special manufacture of these in Canada, and such as are made are not reliable.” Many climbers of the day went to Europe to first get outfitted and climb famous peaks like the Matterhorn with Swiss guides before venturing into the Canadian mountains, sometimes bringing the same Swiss guides.

Footnote: mountain “conquest” has been covered previously, also to note is the concept of “discovery” of places inhabited for generations, such as the ‘discovery’ of Yosemite Valley in 1851, and the celebrated ‘discovery’ of great Takakkaw Falls in Yoho Valley “which rivals the Yosemite in height and surpasses it in volume” by Jean Habel, the German traveler of some note, in 1897 (Fay, 1911).

Alpine Club of Canada

In 1906 Wheeler with Elizabeth Parker founded the Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) with its clubhouse in Banff, and Wheeler became its first president and began his long-term editorship of the Canadian Alpine Journal, first published in 1907. By 1911 the club had 600 members (over 200 women), and Canadian mountaineering in the finest of British tradition had arrived on the continent. The same momentum was building in New Zealand, as well as in other regions of the British Empire. One of the missions of the ACC was to connect and share information with international alpine and geographical associations, and Wheeler became a lead player in the global community of alpine club members, all seeking to ascend and document the mountains of the world. Wheeler was now looking at expanding the ranges of mountaineering and began organizing summer camps in the Canadian Rockies, sometimes referred to as the “Alpine Club of Canada Expeditions.” Two guides from the Glacier House were hired, and all sorts of participants, including many in their quest to become “active Members” of the ACC (requiring an ascent of a 10,000-foot peak) and who first learned of modern mountain climbing techniques from qualified European guides.

While planning the 1909 ACC summer camp in the Rockies’ expanding national park areas (now Yoho and Banff NPs), Wheeler received a letter from Hofrat Dr. E. Pistor, an important member of the Board of Trade in Vienna and member of the Austrian Alpine Club; Pistor had climbed all over the European Alps with his guide Konrad Kain and was a well-respected mountaineer. Guides back then were rarely offered membership in the alpine clubs but Pistor had become good friends with Kain and went to bat for him. Kain had applied for a 1909 season guiding job at the Glacier House, but was unsuccessful as the established Swiss Guides were all returning for the season. The timing of Pistor’s letter of recommendation to the Alpine Club of Canada was right (and perhaps Wheeler was looking for a rock climbing specialist), and he offered Kain a guiding spot for the upcoming ACC summer camp for $2 per day, all expenses, plus another $2 for mountains climbed. Kain went on to become one of the great heroes of early North American climbing, well-known and respected for his quality mountain guiding, hard-working spirit, and alpine & technical rock-climbing breakthroughs. He was the first to bring Eastern Alps rock climbing techniques to the ‘west’.

Footnote: From a footnote in Robinson, 2014 (ref.below): Earlier in the year, Pistor corresponded with both the CPR and the Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) on Kain's behalf to inquire about employment for him as a guide. "Conrad is not only a good, competent man," Pistor wrote, "but a first-class guide and exceptional because he is just as good on rocks as he is on glaciers. He is clever and sympathetic too, he is a 'gamin' with people who like dangers, and careful like a father of 50 with people who are in want of care. Erich Pistor to Arthur O. Wheeler, ACC President, 9 April 1909, WMCR M200/ACOM/52. Pistor’s letter to the CPR was dated February, and the letter to the ACC dated April 9.

The story of Conrad Kain (1883-1934) has the flavor of a Canadian ‘Horatio Alger’ tale—the oft-told timepiece saga of successful mentors who recognize talent, and the neophyte who makes his way and seizes opportunities; through hard work, the individual ‘rises’ to find success. In this regard, Wheeler was one of the most influential in Kain’s ‘rise’, providing him multiple opportunities that would have been otherwise inaccessible.

In the years preceding and during WWI, there is very little information shared between the English (and French) alpine clubs, and alpine clubs from the ‘Triple Alliance’ (German, Austria-Hungary, and Italy—the latter a “neutral” member until 1915), and climbers from these regions were rarely acknowledged outside of the Eastern Alps. Of course, the Eastern Alps by this time is where new lightweight technical rock climbing techniques had already advanced beyond anywhere else in the world, and even though such techniques were disdained by the mountaineers in the British Empire at the time, Wheeler must have known that hiring an Austrian guide, known for his rock climbing skills, would have some implications, as there were plenty of recognized traditional and broadly accepted mountain guides from Switzerland looking for the opportunity to work in the Canadian mountains.

Indeed, Kain had to pretend to be a Swede to get to America, and once in America, he was introduced as a “Swiss Guide” despite his Austrian roots. On the other side of the “pond”, western North American stereotypes mythologized by the German writer Karl May, initially ingrained in Europe and spawning countless “spaghetti Westerns”, influenced the mythology of the wild wild west even in North American culture.

It is only in this context of technological changes providing increased access, and the indigenous and international cultural stereotypes (some that persist today) that can we understand Kain’s contributions to climbing, and how he became the most successful international guide of the era. Before we consider what Kain brought to North American mountaineering, it’s worthwhile to look at his humble beginnings.

Conrad Kain’s story will be told next in “Trains and Kain (part 2).

Author’s Note: This article is informed by Chic Scott’s awesome Story of Canadian Mountaineering (ref.below), with its broad well-researched history, but also inspired to go a bit deeper in what Brian Greenwood writes in the introduction: “When I think about Canadian climbing, I like to think of the pioneers. With the railways for many years the only access to the mountains, … Just getting to the base of most mountains in the early days involved trail building, bushwhacking, pack trains, often major expeditions.” When I climbed in the Purcells in the 1990s, I could only imagine the increased difficulty back then so it has been fun to learn more about how the actual technological changes progressed. (Xaver footnote, rockwork, and SJ trains).

APPENDIX/More Images

REFERENCES (except journals and primary sources tc or noted):

source: A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway in Glacier National Park, British Columbia 1884-1930 by David A.A. Finch 1987.

source: Snow Wars, An Illustrated History of Rogers Pass Glacier National Park, B.C, John Woods, 1983

source: Recent Mountaineering in the Canadian Alps, Geographical Review Vol. 2, No. 1 (Jul., 1916), Charles E. Fay

Alpina Americana (first three publications covering the Sierras, Canadian Rockies, and Alaska from the American Alpine Club)

for next chapter:

Where the Clouds Can Go, Conrad Kain and J. Monroe Thorington, 1954 (reprint from 1935 edition).

CONRAD KAIN: LETTERS FROM A WANDERING MOUNTAIN GUIDE 1906-1933 Zac Robinson 2014. An excellently presented book, with well-researched footnotes, of discovered letters, lost since 1935, of Conrad Kain to Amelie Malek and family.

LINKS to previous writing and research:

Mizzi Langer -- first advertised rock climbing pitons (Mauerhaken)

Climbing Tools and Techniques—1908 to 1939 (Europe, PartA) Myths and Legends

1930s Climbing Tools (Europe, PartC):

Climbing Tools and Techniques—early North American Developments to 1910:

Geography/History review: